Subventricular zone

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (August 2022) |

| Subventricular zone | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| NeuroLex ID | nlx_144262 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

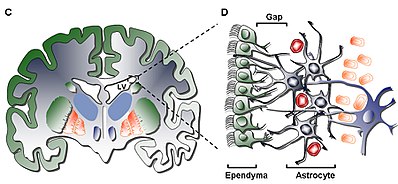

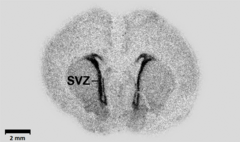

The subventricular zone (SVZ) is a region situated on the outside wall of each lateral ventricle of the vertebrate brain.[2] It is present in both the embryonic and adult brain. In embryonic life, the SVZ refers to a secondary proliferative zone containing neural progenitor cells, which divide to produce neurons in the process of neurogenesis.[3] The primary neural stem cells of the brain and spinal cord, termed radial glial cells, instead reside in the ventricular zone (VZ) (so-called because the VZ lines the inside of the developing ventricles).[4]

In the developing cerebral cortex, which resides in the dorsal telencephalon, the SVZ and VZ are transient tissues that do not exist in the adult.[4] However, the SVZ of the ventral telencephalon persists throughout life. The adult SVZ is composed of four distinct layers[5] of variable thickness and cell density as well as cellular composition. Along with the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the SVZ is one of two places where neurogenesis has been found to occur in the adult mammalian brain.[6] Adult SVZ neurogenesis takes the form of neuroblast precursors of interneurons that migrate to the olfactory bulb through the rostral migratory stream. The SVZ also appears to be involved in the generation of astrocytes following a brain injury.[7]

Structure

Layer I

The innermost layer (Layer I) contains a single layer (monolayer) of ependymal cells lining the ventricular cavity; these cells possess apical cilia and several basal expansions that may stand in either parallel or perpendicular to the ventricular surface. These expansions may interact intimately with the astrocytic processes that are interconnected with the hypocellular layer (Layer II).[5]

Layer II

The secondary layer (Layer II) provides for a hypocellular gap abutting the former and has been shown to contain a network of functionally correlated Glial Fibrillary Acid Protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytic processes that are linked to junctional complexes, yet lack cell bodies except for the rare neuronal somata. While the function of this layer is yet unknown in humans, it has been hypothesized that the astrocytic and ependymal interconnections of Layer I and II may act to regulate neuronal functions, establish metabolic homeostasis, and/or control neuronal stem cell proliferation and differentiation during development. Potentially, such characteristics of the layer may act as a remainder of early developmental life or pathway for cellular migration given similarity to a homologous layer in bovine SVZ shown to have migratory cells common only to higher order mammals.[5]

Layer III

The third layer (Layer III) forms a ribbon of astrocyte cell bodies that are believed to maintain a subpopulation of astrocytes able to proliferate in vivo and form multipotent neurospheres with self-renewal abilities in vitro. While some oligodendrocytes and ependymal cells have been found within the ribbon, they not only serve an unknown function, they are uncommon by comparison to the population of astrocytes that reside in the layer. The astrocytes present in Layer III can be divided into three populations through electron microscopy, with no unique functions yet recognizable; the first type is a small astrocyte of long, horizontal, tangential projections mostly found in Layer II; the second type is found between Layers II and III as well as within the astrocyte ribbon, characterized by its large size and many organelles; the third type is typically found in the lateral ventricles just above the hippocampus and is similar in size to the second type but contains few organelles.[5]

Layer IV

The fourth and final layer (Layer IV) serves as a transition zone between Layer III with its ribbon of astrocytes and the brain parenchyma. It is identified by a high presence of myelin in the region.[5]

Cell types

Four cell types are described in the SVZ:[8]

1. Ciliated Ependymal Cells (Type E): are positioned facing the lumen of the ventricle, and function to circulate the cerebrospinal fluid.

2. Proliferating Neuroblasts (Type A): express PSA-NCAM (NCAM1), Tuj1 (TUBB3), and Hu, and migrate in line order to the olfactory bulb

3. Slow Proliferating Cells (Type B): express Nestin and GFAP, and function to ensheathe migrating Type A Neuroblasts[9]

4. Actively Proliferating Cells or Transit Amplifying Progenitors (Type C): express Nestin, and form clusters interspaced among chains throughout region[10]

Function

The SVZ is a known site of neurogenesis and self-renewing neurons in the adult brain,[11] serving as such due to the interacting cell types, extracellular molecules, and localized epigenetic regulation promoting such cellular proliferation. Along with the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus, the subventricular zone serves as a source of neural stem cells (NSCs) in the process of adult neurogenesis. It harbors the largest population of proliferating cells in the adult brain of rodents, monkeys and humans.[12] In 2010, it was shown that the balance between neural stem cells and neural progenitor cells (NPCs) is maintained by an interaction between the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway and the Notch signaling pathway.[13]

While it has yet to have been studied in-depth in the human brain, the SVZ function in the rodent brain has been, to a certain extent, examined and defined for its abilities. With such research, it has been found that the dual-functioning astrocyte is the dominant cell in the rodent SVZ; this astrocyte acts as not only a neuronal stem cell, but also as a supporting cell that promotes neurogenesis through interaction with other cells.[8] This function is also induced by microglia and endothelial cells that interact cooperatively with neuronal stem cells to promote neurogenesis in vitro, as well as extracellular matrix components such as tenascin-C (helps define boundaries for interaction) and Lewis X (binds growth and signaling factors to neural precursors).[14] The human SVZ is different, however, from the rodent SVZ in two distinct ways; the first is that the astrocytes of humans are not in close juxtaposition to the ependymal layer, rather separated by a layer lacking cell bodies; the second is that the human SVZ lacks chains of migrating neuroblasts seen in rodent SVZ, in turn providing for a lesser number of neuronal cells in the human than the rodent.[2] For this reason, while rodent SVZ proves as a valuable source of information regarding the SVZ and its structure-to-function relationship, the human model will prove significantly different.

Epigenetic DNA modifications have a central role in regulating gene expression during differentiation of neural stem cells. The conversion of cytosine to 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in DNA by DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A appears to be an important type of epigenetic modification occurring in the SVZ.[15]

In addition, some current theories propose that the SVZ may also serve as a site of proliferation for brain tumor stem cells (BTSCs),[16] which are similar to neural stem cells in their structure and ability to differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Studies have confirmed that a small population of BTSCs can not only produce tumors, but they can also maintain it through innate self-renewal and multipotent abilities. While this does not allow for inference that BTSCs arise from neural stem cells, it does raise an interesting question as to the relationship that exists from our own cells to those that can cause so much damage.[citation needed]

Current research

There are currently many different aspects of the SVZ being researched by individuals in the public and private sectors. Such research interests range from the role of the SVZ in neurogenesis, directed neuronal migration, to the previously mentioned tumorigenesis, as well as many others. Below there are summaries of the work of three different lab groups focusing primarily on one aspect of the SVZ; these include the role of SVZ in cell replacement after brain injury, simulation of NSC proliferation, and role in various tumorigenic cancers.

Role in cell replacement after brain injury

In their review, Romanko et al. characterized the impact of acute brain injury on the SVZ. Overall, the authors determined that moderate insults to the SVZ allowed for recovery while more severe injuries caused permanent damage to the region. Additionally, the neural stem cell population within the SVZ is likely responsible for this injury response.[17]

The effects of irradiation on the SVZ provided for a recognition of the amount or dose of radiation that can be given is determined mostly by the tolerance of the normal cells near the tumor. As described, the increasing dose of radiation and age led to decrease in three cell types of the SVZ, yet repair capacity of the SVZ was observed despite the lack of white matter necrosis; this occurred likely because the SVZ was able to gradually replace the neuroglia of the brain. Chemotherapeutics were also tested for their effects on the SVZ, as they are currently used for many diseases yet lead to complications within the central nervous system. To do so, methotrexate (MTX) was used alone and in combination with radiation to find that roughly 70% of the total nuclear density of the SVZ had been depleted, yet given loss of neuroblast cells (progenitor cells), it was remarkable to find that SVZ NSCs would still generate neurospheres similar to subjects that did not receive such treatment. In relation to interruption of blood supply to the brain, cerebral hypoxia/ischemia (H/I) was found to also decrease the cell count of the SVZ by 20%, with 50% of neurons in the striatum and neocortex being destroyed, but the cell types of the SVZ killed were as non-uniform as the region itself. Upon subsequent testing, it was found that a different portion of each cell was eliminated, yet the medial SVZ cell population remained mostly alive. This may provide for a certain resiliency of such cells, with the uncommitted progenitor cells acting as the proliferating population following ischemia. Mechanical brain injury also induces cell migration and proliferation, as was observed in rodents, and it may also increase cell number, negating the previously held notion that no new neuronal cells can be generated.[citation needed]

In conclusion, this group was able to determine that cells in the SVZ are able to produce new neurons and glia throughout life, given it does not suffer damage as it is sensitive to any deleterious effects. Therefore, the SVZ can recover itself following mild injury, and potentially provide for replacement cell therapy to other affected regions of the brain.[citation needed]

Role of neuropeptide Y in neurogenesis

In an attempt to characterize and analyze the mechanism concerning the proliferation of neuronal cells within the subventricular zone, Decressac et al. observed the proliferation of neural precursors in the mouse subventricular zone through injection of the neuropeptide Y (NPY).[18] NPY is a commonly expressed protein of the central nervous system that has previously been shown to stimulate proliferation of neuronal cells in the olfactory epithelium and hippocampus. The peptide’s effects were observed through BrdU labeling and cell phenotyping that provided evidence for the migration of neuroblasts through the rostral migratory stream to the olfactory bulb (confirming previous experiments) and to the striatum. Such data supports the author's hypothesis in that neurogenesis would be stimulated through introduction of such a peptide.[citation needed]

As NPY is a 36 amino acid peptide associated with many physiological and pathological conditions, it has multiple receptors that are broadly expressed in the developing and mature rodent brain. However, given in vivo studies performed by this group, the Y1 receptor displayed specifically mediated neuroproliferative effects through the induction of NPY with increased expression in the subventricular zone. Identification of the Y1 receptor also sheds light on the fact that the phenotype of expressed cells from such mitotic events are actually cells that are DCX+ (neuroblasts that migrate directly to the striatum) type. Along with the effects of NPY injection on striatal dopamine, GABA and glutamate parameters to regulate neurogenesis in the subventricular zone (previous study), this finding is still under consideration as it could be a secondary modulator of the aforementioned neurotransmitters.[citation needed]

As is necessary for all research, this group conducted its experiments with a broad perspective on the application of their findings, which they claimed could potentially benefit potential candidates for endogenous brain repair through stimulation of the subventricular zone neural stem cell proliferation. This natural molecular regulation of adult neurogenesis would be adjunct with therapies of appropriate molecules such as the tested NPY and Y1 receptor, in addition to pharmacological derivatives, in providing for manageable forms of neurodegenerative disorders of the striatal area.[citation needed]

As a potential source of brain tumors

In an attempt to characterize the role of the subventricular zone in potential tumorigenesis, Quinones-Hinojosa et al. found that brain tumor stem cells (BTSCs) are stem cells that can be isolated from brain tumors by similar assays used for neuronal stem cells.[5] In forming clonal spheres similar to neurospheres of neuronal stem cells, these BTSCs were able to differentiate into neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in vitro, yet more importantly capable of initiating tumors at low cell concentrations, providing a self-renewal capacity. It was therefore proposed that a small population of BTSCs with such self-renewal capabilities were maintaining tumors in diseases such as leukemia and breast cancer.[citation needed]

Several characterizing factors lead to the proposed idea of neuronal stem cells (NSCs) being the origin for BTSCs, as they share several features. These features are shown in the figure.

This group provides evidence of the SVZ's apparent role in tumorigenesis as demonstrated by the possession of mitogenic receptors and their response to mitogenic stimulation, specifically type C cells that express the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), making them highly proliferative and invasive. Additionally, the existence of microglia and endothelial cells within the SVZ was found to enhance neurogenesis, as well as providing for some directional migration of neuroblasts from the SVZ.[citation needed]

Recently, the human SVZ has been characterized in brain tumor patients at phenotypic and genetic level. These data reveal that in half of the patients the SVZ is an exact site of tumorigenesis whereas in the remaining patients it represents an infiltrated region.[19] Thus, it is distinctly possible that in humans a relationship exists between the NSC generation of the region and the consistently self-renewing cells of primary tumors that give way to secondary tumors once removed or irradiated.[citation needed]

While it remains to be definitely proven whether the SVZ stem cells are the cell of origin for brain tumors such as gliomas, there is strong evidence that suggests increased tumor aggressiveness and mortality in those patients whose high-grade gliomas infiltrate or contact the SVZ.[20][21]

In prostate cancer, tumor-induced neurogenesis is characterized by the recruitment of neural progenitor cells (NPC) from SVZ. NPCs infiltrate the tumor where they differentiate into autonomic neurons (adrenergic neurons mainly) that stimulate tumor growth.[22]

See also

References

- ^ Popp A, Urbach A, Witte OW, Frahm C (2009). Reh TA (ed.). "Adult and Embryonic GAD Transcripts Are Spatiotemporally Regulated during Postnatal Development in the Rat Brain". PLoS ONE. 4 (2): e4371. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004371. PMC 2629816. PMID 19190758.

- ^ a b Quiñones-Hinojosa, A; Sanai, N; Soriano-Navarro, M; Gonzalez-Perez, O; Mirzadeh, Z; Gil-Perotin, S; Romero-Rodriguez, R; Berger, MS; Garcia-Verdugo, JM; Alvarez-Buylla, A (Jan 20, 2006). "Cellular composition and cytoarchitecture of the adult human subventricular zone: a niche of neural stem cells". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 494 (3): 415–34. doi:10.1002/cne.20798. PMID 16320258. S2CID 11713373.

- ^ Noctor, SC; Martínez-Cerdeño, V; Ivic, L; Kriegstein, AR (February 2004). "Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases". Nature Neuroscience. 7 (2): 136–44. doi:10.1038/nn1172. PMID 14703572. S2CID 15946842.

- ^ a b Rakic, P (October 2009). "Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (10): 724–35. doi:10.1038/nrn2719. PMC 2913577. PMID 19763105.

- ^ a b c d e f Quiñones-Hinojosa, A; Chaichana, K (Jun 2007). "The human subventricular zone: a source of new cells and a potential source of brain tumors". Experimental Neurology. 205 (2): 313–24. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.016. PMID 17459377. S2CID 20491538.

- ^ Ming, GL; Song, H (May 26, 2011). "Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions". Neuron. 70 (4): 687–702. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. PMC 3106107. PMID 21609825.

- ^ Lim, Daniel A.; Alvarez-Buylla, Arturo (May 2016). "The Adult Ventricular–Subventricular Zone (V-SVZ) and Olfactory Bulb (OB) Neurogenesis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 8 (5): a018820. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a018820. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 4852803. PMID 27048191.

- ^ a b Doetsch, F; García-Verdugo, JM; Alvarez-Buylla, A (Jul 1, 1997). "Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (13): 5046–61. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05046.1997. PMC 6573289. PMID 9185542.

- ^ Luskin, MB (Jul 1993). "Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone". Neuron. 11 (1): 173–89. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-U. PMID 8338665. S2CID 23349579.

- ^ Doetsch, F; Caillé, I; Lim, DA; García-Verdugo, JM; Alvarez-Buylla, A (Jun 11, 1999). "Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain". Cell. 97 (6): 703–16. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80783-7. PMID 10380923.

- ^ Lim, DA; Alvarez-Buylla, A (Jun 22, 1999). "Interaction between astrocytes and adult subventricular zone precursors stimulates neurogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (13): 7526–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7526. PMC 22119. PMID 10377448.

- ^ Gates, MA; Thomas, LB; Howard, EM; Laywell, ED; Sajin, B; Faissner, A; Götz, B; Silver, J; Steindler, DA (Oct 16, 1995). "Cell and molecular analysis of the developing and adult mouse subventricular zone of the cerebral hemispheres". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 361 (2): 249–66. doi:10.1002/cne.903610205. PMID 8543661. S2CID 12720709.

- ^ Aguirre A, Rubio ME, Gallo V (September 1998). "Notch and EGFR pathway interaction regulates neural stem cell number and self-renewal". Nature. 467 (7313): 323–7. doi:10.1038/nature09347. PMC 2941915. PMID 20844536.

- ^ Bernier, PJ; Vinet, J; Cossette, M; Parent, A (May 2000). "Characterization of the subventricular zone of the adult human brain: evidence for the involvement of Bcl-2". Neuroscience Research. 37 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1016/S0168-0102(00)00102-4. PMID 10802345. S2CID 45832289.

- ^ Wang Z, Tang B, He Y, Jin P. DNA methylation dynamics in neurogenesis. Epigenomics. 2016 Mar;8(3):401-14. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.119. Epub 2016 Mar 7. Review. PMID 26950681

- ^ Parent JM, von dem Bussche N, Lowenstein DH (2006). "Prolonged seizures recruit caudal subventricular zone glial progenitors into the injured hippocampus" (PDF). Hippocampus. 16 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1002/hipo.20166. hdl:2027.42/49285. PMID 16435310. S2CID 17643839.

- ^ Romanko, MJ; Rola, R; Fike, JR; Szele, FG; Dizon, ML; Felling, RJ; Brazel, CY; Levison, SW (Oct 2004). "Roles of the mammalian subventricular zone in cell replacement after brain injury". Progress in Neurobiology. 74 (2): 77–99. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.07.001. PMID 15518954. S2CID 44399750.

- ^ Decressac, M; Prestoz, L; Veran, J; Cantereau, A; Jaber, M; Gaillard, A (Jun 2009). "Neuropeptide Y stimulates proliferation, migration and differentiation of neural precursors from the subventricular zone in adult mice". Neurobiology of Disease. 34 (3): 441–9. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.017. PMID 19285132. S2CID 24661524.

- ^ Piccirillo, Sara G. M.; Spiteri, Inmaculada; Sottoriva, Andrea; Touloumis, Anestis; Ber, Suzan; Price, Stephen J.; Heywood, Richard; Francis, Nicola-Jane; Howarth, Karen D. (2015-01-01). "Contributions to Drug Resistance in Glioblastoma Derived from Malignant Cells in the Sub-Ependymal Zone". Cancer Research. 75 (1): 194–202. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3131. ISSN 0008-5472. PMC 4286248. PMID 25406193.

- ^ Mistry, A.; et al. (2016). "Influence of glioblastoma contact with the lateral ventricle on survival: a meta-analysis". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 131 (1): 125–133. doi:10.1007/s11060-016-2278-7. PMC 5262526. PMID 27644688.

- ^ Mistry, A.; et al. (2017). "Decreased survival in glioblastomas is specific to contact with the ventricular-subventricular zone, not subgranular zone or corpus callosum". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 132 (2): 341–349. doi:10.1007/s11060-017-2374-3. PMC 5771712. PMID 28074322.

- ^ Cervantes-Villagrana RD, Albores-García D, Cervantes-Villagrana AR, García-Acevez SJ (18 June 2020). "Tumor-induced Neurogenesis and Immune Evasion as Targets of Innovative Anti-Cancer Therapies". Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5 (1): 99. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-0205-z. PMC 7303203. PMID 32555170.