User:HammyJammies/Ammit

| Ammit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | Egyptian: ꜥm-mwt[1]

(devourer of the dead)

| ||||||

*(Notes of where citations are currently in the main article) *

Ammit[edit]

Ammit (/ˈæmɪt/; Ancient Egyptian: ꜥm-mwt, "Devourer of the Dead"; also rendered Ammut or Ahemait) was an ancient Egyptian goddess with the forequarters of a lion, the hindquarters of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile—the three largest "man-eating" animals known to ancient Egyptians. In ancient Egyptian religion, Ammit played an important role during the funerary ritual, the Judgment of the Dead.

Nomenclature[edit]

Ammit (Ancient Egyptian: ꜥm-mwt; Ʒmt mwtw)(Cite #2) means 'devourer of the dead" [2](Cite #1) ('Devoureress of the Dead') (Cite #4 &6) or 'Swallower of the Dead',(Cite #2) where ꜥm is the verb 'to swallow', (Cite #7) and mwt signifies 'the dead', more specifically the dead who had been adjudged not to belong to the akhu 'blessed dead' who abided by the code of truth (ma'at).[2]

Iconography[edit]

Ammit is denoted a female entity, commonly depicted with: the head of a crocodile, the forelegs and upper body of a lion (or leopard), and the hind legs and lower body of a hippopotamus.[3] The combination of three deadly predators: crocodile, lion, and hippo, suggests that no one can escape annihilation, even in the afterlife (Cite #4). She is part lioness, but her leonine features may present in the form of a mane, which is usually associated with male lions (Remove Cite #19). In the Papyrus of Ani, Ammit is adorned with a tri-colored nemes, (Cite #10) which were worn by pharaohs as a symbol of kingship.

Versions of the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom started to include Ammit.[4] During the eighteenth dynasty, the crocodile-lion-hippopotamus hybrid was the conventional depiction of Ammit. She appeared in scenes showing the Judgment of the Dead, in tombs and funerary papyri. In this scene, Ammit is shown with other Egyptian gods in Duat, waiting to learn if she can consume the heart of the deceased. A stylistic shift occurred, during the Third Intermediate Period. Around the twenty-first dynasty, the Judgment of the Dead scene was painted on the interior and exterior of coffins. The coffin lid of Ankh-hor, a chief from the twenty-second dynasty featured Ammit bearing the head of a hippopotamus, and the body of a dog.[4] While the Papyrus of Nes-min (ca. 300-250 BCE) from the Ptolemaic Period, portrayed Ammit with the head of a crocodile, and the body of a dog.[5]

Role in ancient Egyptian Religion[edit]

Unlike other gods featured in ancient Egyptian religion, Ammit was not worshipped.[3] Instead, Ammit was feared and believed to be a demon rather than a deity, due to her role as the 'devourer of the dead'.[3] During the New Kingdom, deities and demons were differentiated by having a cult or center of worship. Demons in ancient Egyptian religion had supernatural powers and roles, but were ranked below the gods and did not have a place of worship.[6] In the case of Ammit, she was a guardian demon. A guardian demon was tied to a specific place, such as Duat. Their appearance was based on a hybrid of an animal or a human and was denoted so the dead could recognize them. Guardian demons that appeared as a hybrid of animals were an amalgamation of traits meant to be feared and to differentiate them from deities associated with humanity.[6]

Prior to the New Kingdom and the creation of Chapter 125 in the Book of the Dead, Ammit did not have a large presence in ancient Egyptian religion. However, Khonsu, the god of the moon, was depicted as a 'devourer of the dead and hearts' in Old Kingdom pyramid texts and Middle Kingdom coffin texts.[7]

Throughout the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, a collection of spells was created to form the Coffin Texts. In Spell 310, Khonsu burned hearts heavier than the feather of ma'at during the Judgment of the Dead.[8][7] In Spell 311, Khonsu devoured the hearts of the gods and the dead. Divine hearts were devoured for their power. Hearts deemed impure during judgment were devoured, leaving the deceased trapped in Duat.[9][7] These spells were among those adapted into the Book of the Dead starting in the New Kingdom.

Spells 310 and 311 of the Coffin Texts are referred to in Chapters 79, and 125 in the Book of the Dead. Chapter 79 refers to the burning of the heart, while the scene of judgment and devouring of hearts is found in Chapter 125.[7] Instead of Khonsu devouring the heart of the dead, Ammit was referred to as the 'devourer of the dead'. Ammit was present during the weighing of the heart, usually near the scale waiting to learn the results. If the heart of the dead was impure, she ate their heart leaving them soulless and trapped in Duat.[10]

Weighing of the Heart[edit]

The Book of the Dead was a collection of funerary texts used to guide the dead to Duat, the Egyptian underworld. The process of the Judgment of the Dead was described in Chapter 125.[11] The ruler of Duat, Osiris, presided over judgment. New Kingdom depictions of this scene occurred at the Hall of the Two Truths (or Two Maats).[2] Anubis, the Guardian of the Scales, conducted the dead towards the weighing scale. Ammit would be situated near the scale, awaiting the results. While Thoth, the god of hieroglyphs and judgment, would record the results. The heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma'at, the goddess of truth.[12] The feather of Ma'at symbolized the balance, and truthfulness needed to be present during one's lifetime. The heart or Ib, represented the individual's soul and was the key to traveling to Aaru.[13]

In Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, the deceased is given a series of declarations to recite at the Judgment of the Dead. The Declaration of Innocence was a list of 42 sins the deceased was innocent of committing. The Declaration to the Forty-two Gods and The Address to the Gods were recited directly to the gods, proclaiming the deceased's purity and loyalty.[11]

After the declarations are recited, their heart is weighted. If the heart was weighted less than the feather of Ma'at, the deceased was ruled to be pure. Thoth recorded the result and Osiris would allow the deceased to continue their voyage toward Aaru and immortality. If the heart was heavier than the feather of Ma'at, the deceased was deemed impure. Ammit would devour their heart, leaving the deceased without a soul. Ancient Egyptians believed the soul would become restless forever, dying a second death. Instead of living in Aaru, the soulless individual would be stuck in Duat.[10]

Ammit is often depicted sitting in a crouched position near the scale, ready to eat the heart. Ancient Egyptians were buried with a copy of the Book of the Dead, guaranteeing they would be successful at the Judgment of the Dead. Thus, Ammit was left hungry without any hearts to eat, and the consecrated dead was then able to bypass the Lake of Fire, featured in Chapter 126 of the Book of the Dead.[14][15]

Gallery[edit]

-

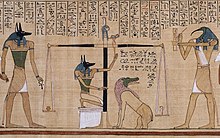

Full view of the Weighing of the Heart from the Papyrus of Ani. Ammit is shown at the far right, near Thoth. Ca. 1250 BCE, Nineteenth Dynasty.

-

Full view of the Weighing of the Heart from the Papyrus of Hunefer. Ammit is shown next to the scale. Anubis is on her left, and Thoth on her right. Ca. 1275 BCE, Nineteenth Dynasty.

-

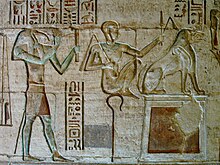

Full view of the Weighing of the Heart from the Temple of Hathor in Deir el-Medina. Thoth is seen to the right of the scale, while to the right, Ammit sits on top of a pedestal.

References[edit]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

woerterbuchwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Taylor, John H. (2001). "Death and Resurrection in Ancient Egyptian Society". Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 9780226791647.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt. Internet Archive. Thames & Hudson. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- ^ a b Taylor, John H. (2019). "The Mummies and Coffins of Ankh-hor and Heribrer". In Kalloniatis, Faye (ed.). The Egyptian Collection at Norwich Castle Museum: Catalogue and Essays. Oxbow Books. p. 23. ISBN 9781789251999.

- ^ Peck, William H. (2000). "The Papyrus of Nes-min: An Egyptian Book of the Dead". Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts. 74 (1/2): 20–31. ISSN 0011-9636 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Lucarelli, Rita (September 2010). Wendrich, Willeke; Dieleman, Jacco; Frood, Elizabeth; Baines, John (eds.). "Demons (Benevolent and Malevolent)". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1: 2–6.

- ^ a b c d Adel Zaki Nasr, Youmna (December 12, 2022). "Apotropaic Roles of Khonsu in the Ancient Egyptian Religion during the Dynastic Period" (PDF). Research Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels (12). Mansoura University: 541–545.

- ^ Faulkner, Raymond O. (1973). The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts: Volume I Spells 1-354. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips Ltd. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0 85668 005 2.

- ^ Faulkner, Raymond O. (1973). The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts: Volume I Spells 1-354. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips Ltd. pp. 228–229. ISBN 0 85668 005 2.

- ^ a b Kleiner, Fred S. (2020-01-01). Gardner's Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective, Volume I. Cengage Learning. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-357-37048-3.

- ^ a b Lichtheim, Miriam (April 3, 2006). Ancient Egyptian literature : a book of readings. Volume II, The New Kingdom. Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 132-139. ISBN 978-0-520-93306-4. OCLC 778435126.

- ^ Aronin, Rachel; et al. (Meg Gundlach) (2008). "Divine Determinatives in the Papyrus of Ani". In Griffin, Kenneth (ed.). Current Research in Egyptology 2007: Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Conference. Vol. 8. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 8, 10–11. ISBN 978-1-84217-329-9.

- ^ de Ville, Jacques (Fall 2011). "Mythology and the Images of Justice". Law and Literature. 23 (3). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 336–337. doi:10.1525/lal.2011.23.3.324. ISSN 1535-685X – via JSTOR.

- ^ Janes, Regina M. (2018). "Impermanent Eternities: Egypt, Sumer, and Babylon, Ancient Israel, Greece, and Rome". Inventing Afterlives: The Stories We Tell Ourselves About Life After Death. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 40–42. doi:10.7312/jane18570.5. ISBN 978-0-231-18570-7.

- ^ Snape, Steven (2011). "Rekhmire and the Tomb of the Well-Known Soldier". Ancient Egyptian Tombs: The Culture of Life and Death. John Wiley & Sons. p. 198. ISBN 9781405120890.