User:Phil wink/Chaucer's meter

This is an essay. It contains the advice or opinions of one or more Wikipedia contributors. This page is not an encyclopedia article, nor is it one of Wikipedia's policies or guidelines, as it has not been thoroughly vetted by the community. Some essays represent widespread norms; others only represent minority viewpoints. |

| This page in a nutshell: What are Geoffrey Chaucer's two types of verse line? and what should we call them? |

Summary[edit]

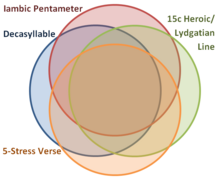

Geoffrey Chaucer's verse is written almost exclusively in 2 meters, which we may preliminarily call the "short line" and the "long line". What is the best way to characterize them? "Octosyllables" and "decasyllables" have a strong claim, especially historically; but "iambic tetrameter" and "iambic pentameter" appear to be the terms that best describe the lines' actual structure. "4-beat" or "5-beat" (or "-ictic" or "-stress") and "heroic line" carry connotations that may be deceptive. Related topics are discussed by the bye.

Background[edit]

Chaucer's verse is written almost exclusively in 2 meters, which we may preliminarily call the "short line" (e.g. in The Romaunt of the Rose, The Book of the Duchess, and The House of Fame) and the "long line" (e.g. in Troilus and Criseyde and most of The Canterbury Tales). The long line especially is called many things by various sources. As of 19 December 2012, the Wikipedia Canterbury Tales article (permanent link) states "It is a decasyllable line, probably borrowed from French and Italian forms, with riding rhyme and, occasionally, a caesura in the middle of a line. His meter would later develop into the heroic meter of the 15th and 16th centuries and is an ancestor of iambic pentameter." However, the Knight's Tale article (permanent link) states "The story is written in iambic pentameter end-rhymed couplets." It may not be fair to blame this proliferation of terms and apparent contradictions on chaotic editing by numerous Wikipedians passing in the night. Consider that George T. Wright uses "decasyllable", "iambic pentameter", and "heroic line" interchangeably for Chaucer's long line,[1] while Suzanne Woods explicitly denies that it is iambic pentameter.[2] Elsewhere "heroic line" has different meanings for different authors and — distressingly — the metrical discussion in the Riverside Chaucer characterizes Chaucer's long lines as "5-stress lines".[3]

In order to name the meter correctly, we must consider competing explanations of what is going on in the lines, and the sometimes shifting and overlapping terminology attached to these conceptions. We'll focus primarily on Chaucer's long line since this is the stickiest wicket.

Versification and its discontents[edit]

Very broadly, metrical verse has 2 structure types:

- "Vertical": the relations of a line to those before and after, in English chiefly implemented through rhyme. This is "stanza" or "rhyme scheme".

- "Horizontal": the structure of syllables within a line. This is "meter".

There is really no doubt about Chaucer's (or usually anyone's) vertical intentions. There is still debate about his meter. There are 3 broad reasons for this.

- The study of versification is "a field which in historical terms has been (it is not too extreme to say) a great mass of ignorance, confusion, superficial thinking, category mistakes, argument by spurious analogy, persuasive definitions, and gross abuses of both concepts and terms."[4] And, if that were not enough, "[t]he study of Middle English versification may be as much as a century behind that of Old English."[5]

- We don't have a CD of Chaucer reading his own works, which means we lack definitive knowledge of how many syllables were intended to sound for some words (and this is an even more complex question than how many syllables the words "had"). A similar case prevails for which syllables were meant to receive primary stress. Metrically, these are more serious problems even than our lack of any authorial text, which is also vexing.

- Particularly for the "long line", several contending metrical systems have broad swaths of overlap. In other words, well-formed results of distinct rules will often be indistinguishable from each other; different metrical grammars can generate many of the same verse lines.

Fortunately advances in linguistics, and an associated pressure on metrics, are improving the first 2 issues, which in turn shed better light on the third.

Contending metrical systems[edit]

We'll evaluate 4 chief metrical conceptions, all of which could possibly have been used by Chaucer, and all of which could generate many of his lines. Naturally some simplification will be inevitable; nevertheless the distinctions will be quite fine-grained. Inevitably labels used here (e.g. "decasyllable", "iambic pentameter") will not designate exactly the same thing to all metrists; my hope is merely that I have been internally consistent and have used the best available word for each phenomenon indicated.

Decasyllabic verse[edit]

The décasyllabe is a French verse line which Chaucer was certainly familiar with, and was certainly influenced by. Its basic structure is

◌ ◌ ◌ / (×) | ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / (×)

- where ◌ = any syllable; / = a stressed syllable; × = an unstressed syllable; () = optional ; and | = a caesura.

However, the French poets Chaucer was following avoided the so-called "epic caesura" so his model would have been a slightly simplified

◌ ◌ ◌ / | ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / (×)

occurring alongside the less frequent "lyric caesura" version of the line:

◌ ◌ / × | ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / (×) [6]

Chaucer also well knew the closely-related Italian endecasillabo which is more complex in structure. Its basic varieties are the a minore and a maiore, both available with masculine or feminine caesuras, for a total of 4 main templates:[7]

a minore M: ◌ ◌ ◌ / | ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / <×> a maiore M: ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / | ◌ ◌ ◌ / <×> a minore F: ◌ ◌ ◌ / × | ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / <×> a maiore F: ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / × | ◌ ◌ / <×>

- where <x> = predominant, but may occasionally be absent or realized with 2 unstressed syllables.[8]

Because Italian had stronger lexical stress than French, most endecasyllabic lines had more stressed syllables than the 2 required, and exhibited a somewhat iambic tendency.[9]

Although many metrists focus on French verse as the most significant influence on Chaucer's long line,[10] Chaucer's variable caesura, avoidance of the French lyric caesura, and iambic tendency argue strongly for the primacy of the Italian endecasyllabo.[11]

For "decasyllable" or "decasyllabic line" (or even "endecasyllable" or "endecasyllabic line") to be the best term for Chaucer's long line, then his practice would have to conform more closely to these models than any other put forward; even though these lines manifestly influenced him, if he altered them enough, then a different pattern and a different term will be appropriate.

5-stress line[edit]

Norman Davis characterizes Chaucer's lines as "four-stress" and "five-stress".[12] A "5-stress line", without further characterization, would have to be something like this:

∴ / ∴ / ∴ / ∴ / ∴ / ∴

- where ∴ = 0 to 3 unstressed syllables, though most often 1 or 2.

I don't believe Davis, or anyone else, has ever thought Chaucer had this in his head. We can, I think, take this term off the table. But it will behoove us to understand in some detail why this term fails. There is an obvious reason that this is a bad description: the pattern's unstressed syllables would have to be much more constrained to reflect Chaucer's actual practice. But there is a less-obvious, but possibly more important, reason: if Chaucer's long line is characterized by 5 prominent syllables, they are prominent not because they are stressed, but because they are ictic.

Digression on stress[edit]

Stress is a characteristic of a syllable. On one hand English stress is generally conceded to occur over a continuum on which only an unpronounced syllable would be truly "unstressed"; on the other hand, 3 levels are broadly accepted as linguistically valid:

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| Primary | The primarily stressed syllable in content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs). |

| Secondary | The secondarily stressed syllables of polysyllabic content words; the most strongly stressed syllable in polysyllabic function words (auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, pronouns, prepositions); subsidiary stress in compound words. |

| Unstressed | Unstressed syllables of polysyllabic words; monosyllabic function words. |

For metrical purposes often primary stress is what counts, but even including secondary stress does not get us 5 of anything in this thoroughly regular line of Chaucer's:

/ / / Bifil that in that seson on a day, CT: General Prologue, line 19[13]

Digression on ictus[edit]

However, ictus — a position felt as a metrical beat — allows us to consider not just the syllable in and of itself, but the metrical function of the syllable in the context of its neighboring syllables. Here is the same line with both its ictuses and approximate stress levels noted:

1 4 1 2 1 4 1 2 1 4 × / × / × / × / × / Bifil that in that seson on a day,

- where / = ictus; × = nonictus; 1 = lightest stress; 4 = heaviest stress

- Note the change in the meaning of the notational symbols. For all subsequent scansions, I will designate whether the contrasts are between stress/unstress or ictus/nonictus by defining "/".

Here we see that as long as the syllable can be sensed as more prominent than its neighbors, it can qualify as ictic even with low stress ("promotion"); conversely a fairly strongly-stressed syllable between 2 even more prominent syllables can function as a nonictus ("demotion").

Heroic line[edit]

What is a heroic line? Depends on who you ask. Most broadly, its meaning is culturally dependent: "Heroic meter is the meter characteristic of heroic poetry"; thus in classical Greek and Latin it is the dactylic hexameter; in French it is either the alexandrine or the décasyllabe, depending on which is culturally predominant in the period in question.[14] Note that the term is not dependent upon the content of the verse, only the form; trivial verses can be written in heroic meter.

" 'Heroic verse' is still today the most neutral term for the 10-syllable, 5-stress line in English otherwise called the 'iambic pentameter' or decasyllable. Each of the latter two terms, while acceptable for general usage, carries with it connotations which are not historically accurate in every age, hence should be used with care."[15] Surely we have a winner? Unfortunately, no. To use the neutral term "heroic line" for Chaucer's long line merely excuses us from our goal of characterizing it as exactly as we can; thus it should be a last resort. Moreover, although as a technical term it implies neither heroic couplets nor heroic subject matter, it may be difficult for lay readers to ignore these unwanted impressions.

But most significantly, the term "heroic line" has developed specific implications for English verse at right around this period...

"Fifteenth-Century Heroic"[edit]

Because of its metrically agnostic, culturally dependent character, C. S. Lewis coined the term "Fifteenth-Century Heroic" to describe the long lines of the English followers of Chaucer such as John Lydgate, Thomas Hoccleve, Alexander Barclay, and Stephen Hawes — and some of the long lines of Sir Thomas Wyatt. Lewis defines this meter as "a long line divided by a sharp medial break into two half-lines, each half-line containing not less than two or more than three stresses, and most half-lines hovering between two and three stresses..."[16]

What emerges is an exceedingly flexible line, a "nursery-rhyme metre":[17]

∴ / ∴ / ∴ (/ ∴) | ∴ / ∴ / ∴ (/ ∴)

- where when a third stress is present in a half-line, one of the stresses (not necessarily the third) is usually secondary.

- / = stress

Lydgatian line[edit]

Wright also mentions the "fifteenth-century heroic line" in reference to Wyatt, but especially Lydgate. His grammar of the Lydgatian line is less free-wheeling than Lewis's "fifteenth-century heroic", and ultimately derives from Jakob Schipper's 16 types of English "five-foot" verse.[18] Though even more variations are possible,[19] the basic structure is:

(×) / × / (×) | (×) / × / × / (×)

- / = ictus

or, with a less-frequent later caesura:

(×) / × / × / (×) | (×) / × / (×)

Since each of the 4 optional unstressed syllables can be present or absent independently, 16 varieties for each caesural position are possible. However, Duffell notes that a negligible number of Lydgate's lines move the caesura from his usual 2 + 3 position; also that occasionally "interior" weak positions are absent or realized with 2 syllables.[20] So possibly a better scheme for Lydgate's line is:

<:> / : / <:> | <:> / : / : / <:>

- where : = 0 to 2 nonictic syllables, predominantly 1; and <:> = more likely than ":" to be realized by 0 or 2 syllables.

Iambic pentameter[edit]

At least since Skeat's edition of 1894-1897,[21] the predominant view seems to be that Chaucer was the initiator of English iambic pentameter verse more or less as we know it today. This is, for example, Wright's stance.[22]

One of the biggest hurdles to using this term for Chaucer's long line is evolutionary: it is generally agreed that the long lines used by English poets from, say, Surrey to Tennyson form a continuous metrical tradition (though with stricter or looser tendencies prevailing in different periods).[23] This line is most often called (and is called here) "iambic pentameter". Let us call this the "IP Tradition". A problem arises. We have a descendancy of meter which, simplified, looks like this:

- Chaucer's long line (??) → Lydgate's line (not iambic pentameter) → IP Tradition

In biological evolution, it would be impossible for Chaucer's long line to be the same as that of the IP Tradition; it would be a bit like birds evolving back into dinosaurs today. But culture is not biology, and though we should have our suspicions, the case is not impossible.

At its core, the deceptively simple-looking iambic pentameter works something like this:

× / × / × / × / × / (×)

- where any 2 positions may switch places, provided the 3rd remains intact[24]

- / = ictus

It comes as a relief that statistical and comparative work over the past decades is coming to a consensus. Charles Barber and Nicolas Barber have proved statistically that Chaucer used unelided final-e to maintain a 10-syllable norm,[25] rendering looser metrical theories untenable. Tarlinskaja firmly categorizes Chaucer's short and long lines as "syllabo-tonic" — that is, iambic tetrameter and iambic pentameter — as opposed to syllabic verse or varieties of stress verse;[26] Gasparov, surely as a result of Tarlinskaja's own work, echoes this finding.[27] Duffell, too, confirms Chaucer's claim to iambic pentameter, noting that John Gower wrote (a few) similarly regular pentameter lines.[28]

Short line and conclusion[edit]

Interestingly, it is with Chaucer's short line that Duffell breaks company with received wisdom. It is neither an octosyllable nor an iambic tetrameter: it is a transitional 4-ictic dolnik.[29] This is, in lay terms, a slightly loose iambic tetrameter — but with just frequent enough loss of the first unstressed syllable, and realization of normally single nonictic positions with 2 unstressed syllables — to render either the terms "octosyllable" or "iambic tetrameter" imprecise. Duffell awards the title of inventor of the true English iambic tetrameter to Chaucer's (more regular) friend, Gower.[30]

Chaucer's long line is iambic pentameter; his short line may be called iambic tetrameter, but might more accurately be called a "transitional" or "loose" iambic tetrameter.

Postscript: other theories[edit]

The "four-beat heresy"[edit]

Between 1954 and 1971 James G. Southworth and Ian Robinson proposed largely independent hypotheses of Chaucer's verse rhythm, both arguing against syllabic regularity and the regular pronunciation of final-e,[31] and in favor of "the four-beat heresy" (as Paull F. Baum called it[32]) which has ties to Northrup Frye's statement that a "four-stress line seems to be inherent in the structure of the English language."[33] These hypotheses place Chaucer's versification closer to the alliterative lines of William Langland or even the free verse of the 20th century than to continental models or the IP Tradition. They have never attained broad acceptance and, as noted above, the fact that Chaucer used unelided final-e to maintain a 10-syllable norm has since been statistically proven.

Halle-Keyser[edit]

In 1966 Morris Halle and Samuel Jay Keyser published the first generative account of meter, applied specifically to Chaucer's long line. But they did not thereby distinguish it from later lines; rather they simply assumed that Chaucer was the first of many authors in the IP Tradition, and that a generative explanation of Chaucer's long line would more or less furnish an explanation for the rest.[34] Therefore theirs constitutes a new argument, not about what Chaucer's long line is, but what iambic pentameter is.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Wright 1988, pp 20-27.

- ^ Woods 1984, pp xi, 32.

- ^ Benson 1987, pp xlii-xliii.

- ^ Brogan 1981, p xii. = Brogan 1999, p x.

- ^ Brogan 1981/1999, p 529.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 83.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 86.

- ^ Preminger & Brogan 1993 s.v. "Hendecasyllable" p 515.

- ^ Gasparov 1996, p 123.

- ^ e.g. Woods 1984, pp 24-32; Benson 1987, pp xlii-xliii.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 87.

- ^ Benson 1987, xlii-xliii.

- ^ All lines quoted from Benson 1987, unless otherwise noted.

- ^ Preminger & Brogan 1993, "Heroic Verse" p 524.

- ^ Preminger & Brogan 1993, "Heroic Verse" p 524.

- ^ Lewis 1939, 50.

- ^ Lewis 1939, 51.

- ^ Wright 1988, p 28-29; Schipper 1910, p 209-212.

- ^ The examples shown here follow Wright's more modest grammar, which focuses specifically on Lydgate's practice. Schipper — in part because his system is meant to house all broadly heroic verse from Chaucer to Lydgate to Wyatt to Donne to Tennyson, in part because of his unhealthy obsession with caesurae — multiplies the system out almost beyond belief.

- ^ Duffel 2008, p 102-03. Wright also allows for "double onset" — 2 unstressed syllables in the first position of either half-line.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 94 n 19.

- ^ Wright 1988, 20-27.

- ^ e.g. Lewis 1939, p 46; Thompson 1966, p 1; Groves 1998, pp 11-12.

- ^ The line-final (×) cannot count as an intact 3rd, disallowing a switch between positions 9 & 10. This is a simplification of Groves's formula (1999, p 107-09), but its practical results correspond closely with the conception of Attridge, as well as with those of relatively strict foot-scanners such as Wright and Steele. Statistical and generative metrists do not consider positions to move under any circumstances, but record various types of "mismatches" between syllable and position.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 84. This 10-syllable norm freely allows 1 or occasionally 2 unstressed syllables after the 10th (and final stressed) syllable, as is common in the décasyllabe, the endecasillabo, and the iambic pentameter.

- ^ Tarlinskaja 1976, p 98.

- ^ Gasparov 1996, pp 183-84.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 84.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 84.

- ^ Duffell 2008, p 85.

- ^ Gaylord 1976, pp 38,42.

- ^ Gaylord 1976, p 36.

- ^ From Anatomy of Criticism, quoted in Gaylord 1976, p 36.

- ^ Gaylord 1976, p 67.

References[edit]

- Attridge, Derek (1982), The Rhythms of English Poetry, New York: Longman, ISBN 0-582-55105-6

- Benson, Larry D., ed. (1987), The Riverside Chaucer (3rd ed.), Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 0-395-29031-7

- Brogan, T.V.F. (1999) [print edition 1981], English Versification, 1570–1980: A Reference Guide With a Global Appendix (Hypertext ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-2541-5 (publisher and ISBN is for the original print edition)

- Duffell, Martin (2008), A New History of English Metre, Studies in Linguistics, vol. 5, London: legenda, ISBN 978-1-907975-13-4

- Gasparov, M.L. (1996), A History of European Versification, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-815879-3

- Gaylord, Alan T. (1976), "Scanning the Prosodists: An Essay in Metacriticism", The Chaucer Review, 11 (1), University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press: 22–82, ISSN 0009-2002

- Groves, Peter L. (1998), Strange Music: The Metre of the English Heroic Line, ELS Monograph Series No.74, Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, ISBN 0-920604-55-2

- Lewis, C.S. (1969) [first published 1939], "The Fifteenth-Century Heroic Line", Selected Literary Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–57

- Preminger, Alex; Brogan, T.V.F., eds. (1993), The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, New York: MJF Books, ISBN 1-56731-152-0

- Schipper, Jakob (1910), A History of English Versification, Oxford: The Clarendon Press

- Steele, Timothy (1999), All the Fun's in How You Say a Thing, Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, ISBN 0-8214-1260-4

- Tarlinskaja, Marina (1976), English Verse: Theory and History, The Hague: Mouton, ISBN 90-279-3295-6

- Thompson, John (1989) [first published 1961], The Founding of English Metre, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-06755-0

- Woods, Susanne (1984), Natural Emphasis: English Versification from Chaucer to Dryden, San Marino: The Huntington Library, ISBN 0-87328-085-7

- Wright, George T. (1988), Shakespeare's Metrical Art, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-07642-7