Xianbei state

Xianbei state Sian'bi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93–234 | |||||||||

| Status | Nomadic confederation | ||||||||

| Religion | Tengriism | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 93 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 234 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

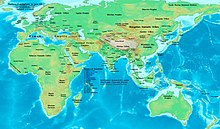

The Xianbei state[1][2] or Xianbei confederation was a nomadic confederation existed in northern Manchuria and eastern Mongolia from 93 to 234 AD. They descended from the Donghu and spoke a Mongolic language.[3]

After the downfall of the Xiongnu, the Xianbei established domination in Mongolia starting from 93 AD. They consisted of Mongolic peoples and reached their height under the rule of Tanshihuai Khan (141–181). Tanshihuai was born in 141. According to the Hou Hanshu his father Touluhou had been serving in the Southern Xiongnu army for three years. Returning from his military duties Touluhou was furious to discover that his wife had become pregnant and given birth to a son. He ordered the child put to death. His wife replied: “When I was walking through the open steppe a huge storm developed with much lightning and thunder. As I looked upward a piece of hail fell into my mouth, which I unknowingly swallowed. I soon found out I had gotten pregnant. After 10 months this son was born. This must be a child of wonder. It is better to wait and see what happens.” Touluhou did not heed her words, so Tanshihuai was brought up secretly in the ger (yurt) of relatives. When Tanshihuai was around 14 or 15 years old he had become brave and sturdy with talent and ability. Once people from another tribe robbed his maternal grandparent’s herds. Tanshihuai pursued them alone, fought the robbers and managed to retrieve all the lost herds. His fame spread rapidly among the Xianbei tribes and many came to respect and trust him. He then put some laws and regulations in force and decided between litigants. Nobody dared to violate those laws and regulations. Because of this, he was elected supreme leader of the Xianbei tribes at the age of 15 and established his ordo (palace) at Mount Darkhan. He defeated the Dingling to the north (around Lake Baikal), Buyeo to the east (north of Korea) and the Wusun to the west (Xinjiang and Ili River). His empire stretched 7000 km and included all the lands of the former Xiongnu.

The Sanguo Zhi records:

Tanshihuai of the Xianbei divided his territory into three sections: the eastern, the middle and the western. From the You Beiping to the Liao River, connecting the Fuyu and Mo to the east, it was the eastern section. There were more than twenty counties. The darens (chiefs) (of this section) were called Mijia, Queji, Suli and Huaitou. From the You Beiping to Shanggu to the west, it was the middle section. There were more than ten counties. The darens of this section were called Kezui, Queju, Murong, et al. From Shanggu to Dunhuang, connecting the Wusun to the west, it was the western section. There were more than twenty counties. The darens (of this section) were called Zhijian Luoluo, Rilü Tuiyan, Yanliyou, et al. These chiefs were all subordinate to Tanshihuai.[4]

Uneasiness at the Han court about this development of a new power on the steppes finally ushered in a campaign on the northern border to annihilate the confederacy once and for all. In 177 AD, 30,000 Han cavalry attacked the confederacy, commanded by Xia Yu (夏育), Tian Yan (田晏) and Zang Min (臧旻), each of whom was the commander of units sent respectively against the Wuhuan, the Qiang, and the Southern Xiongnu before the campaign. Each military officer commanded 10,000 cavalrymen and advanced north on three different routes, aiming at each of the three federations. Cavalry units commanded by chieftains of each of the three federations almost annihilated the invading forces. Eighty percent of the troops were killed and the three officers, who only brought tens of men safely back, were relieved from their posts.

The Hou Hanshu records a memorial submitted in 177 AD:

Ever since the [northern] Xiongnu ran away, the Xianbei have become powerful and populous, taking all the lands previously held by the Xiong-nu and claiming to have 100,000 warriors. … Refined metals and wrought iron have come into the possession of the [Xianbei] rebels. Han deserters also seek refuge [in the lands of the Xianbei] and serve as their advisers. Their weapons are sharper and their horses are faster than those of the Xiong-nu.

Another memorial submitted in 185 AD is recorded by the Hou Hanshu:

The Xianbei people … invade our frontiers so frequently that hardly a year goes by in peace, and it is only when the trading season arrives that they come forward in submission. But in so doing they are only bent on gaining precious Chinese goods; it is not because they respect Chinese power or are grateful for Chinese generosity. As soon as they obtain all they possibly can [from trade], they turn in their tracks to start wreaking damage.

Tanshihuai died in 181 at the age of 40. The Xianbei state of Tanshihuai fragmented following the fall of Budugen (reigned 187-234), who was the younger brother of Kuitoi (reigned 185-187). Kuitou was the nephew of Tanshihuai's incapable son and successor Helian (reigned 181-185).

In 234 after the fall of the last Xianbei Khan Budugen (along with Kebineng) the Xianbei state began to split into a number of smaller independent domains. The 3rd century AD saw both the fragmentation of the Xianbei Empire in 235 and the branching out of the various Xianbei tribes later to establish significant empires of their own. The most prominent branches are the Murong, Tuoba, Khitan, Shiwei and Rouran.

The economic base of the Xianbei was animal husbandry combined with agricultural practice. They were the first to develop the Khanate system,[5] in which formation of social classes deepened, and developments also occurred in their literacy, arts and culture. They used a zodiac calendar and favored song and music. Tengriism was the main religion among the Xianbei people. After they lost control over Mongolia, their descendants in North China later became fully versed in Chinese cultural traditions.[6]

In 235, the Chinese Cao Wei that succeeded the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) in northern China assassinated the last Khan of the Xianbei, Kebineng, and caused disintegration in the Xianbei Kingdom.[7] Thereafter, the Xianbei pushed their way inside the Great Wall and established extensive presence in China from the Sixteen Kingdoms (304–439), Northern Dynasties (386–581),[8][9][10] through the Sui (581–618) and Tang Dynasties (618–907).[11][12][13][14]

The Khitans, known as "Qidan" in Chinese, who founded the subsequent Liao Dynasty (916–1125)[5] in China proper were included in the Yuwen Xianbei in southern Mongolia,[15] who had earlier founded the Western Wei (535–556) and Northern Zhou (557–581)[16] of the Northern Dynasties (386–581) in northern China, in opposition to the Southern Dynasties (420–589) founded by the Chinese in southern China. Their Khitan rule over China through the Liao gave rise to the reference of China known as “Hătāi” and “Cathay” in the Persian and European countries.[17]

The Mongols derived their ancestry from the “Mengwu Shiwei” in the northern Manchuria and northeastern Mongolia. “Mengwu” was a variant Chinese transcription of “Menggu” designated to the Mongols, and “Shiwei” was a variant transcription of the Xianbei, as “Xianbei” was also recorded as “Sian-pie,” “Serbi,” “Sirbi” and “Sirvi”.[18]

See also

Notes

- ^ Ray Huang – Broadening the Horizons of Chinese History, p.135

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis – The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han

- ^ Sanping Chen Agan – Revisited the Tuobas Cultural and Political Heritage, Journal of Asian history, p. 47. 1996

- ^ SGZ 30. 837-838, note. 1.

- ^ a b Wittfogel, Karl August and Chia-sheng Feng (1949). History of Chinese society: Liao, 907–1125. Philadelphia, American Philosophical Society distributed by the Macmillan Co. New York. p. 1.

- ^ Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Kwang-ching Liu – The Cambridge illustrated history of China

- ^ Lü, Jianfu [呂建福], 2002. Tu zu shi [The Tu History] 土族史. Beijing [北京], Zhongguo she hui ke xue chu ban she [Chinese Social Sciences Press] 中囯社会科学出版社.

- ^ Ma, Changshou [馬長壽] (1962). Wuhuan yu Xianbei [Wuhuan and Xianbei] 烏桓與鮮卑. Shanghai [上海], Shanghai ren min chu ban she [Shanghai People's Press] 上海人民出版社.

- ^ Liu, Xueyao [劉學銚] (1994). Xianbei shi lun [the Xianbei History] 鮮卑史論. Taibei [台北], Nan tian shu ju [Nantian Press] 南天書局.

- ^ Wang, Zhongluo [王仲荦] (2007). Wei jin nan bei chao shi [History of Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties] 魏晋南北朝史. Beijing [北京], Zhonghua shu ju [China Press] 中华书局.

- ^ Chen, Yinke [陳寅恪], 1943, Tang dai zheng zhi shi shu lun gao [Manuscript of Discussions on the Political History of the Tang Dynasty] 唐代政治史述論稿. Chongqing [重慶], Shang wu [商務].

- ^ Chen, Yinke [陳寅恪] and Tang, Zhenchang [唐振常], 1997, Tang dai zheng zhi shi shu lun gao [Manuscript of Discussions on the Political History of the Tang Dynasty] 唐代政治史述論稿. Shanghai [上海], Shanghai gu ji chu ban she [Shanghai Ancient Literature Press] 上海古籍出版社.

- ^ Wang, Qinghuai [王清淮] (2008). Tang tai zong [Emperor Taizong of the Tang] 唐太宗. Beijing [北京], Zhongguo she hui ke xue chu ban she [Chinese Social Sciences Press] 中国社会科学出版社.

- ^ Yang, Jun [杨军] and Lü Jingzhi [吕净植] (2008). Xianbei di guo chuan qi [Legends of the Xianbei Empires] 鲜卑帝国传奇. Beijing [北京], Zhongguo guo ji guang bo chu ban she [Chinese International Broadcasting Press] 中国国际广播出版社.

- ^ Cheng, Tian [承天] (2008). Qidan di guo chuan qi [Legends of the Khitan Empires] 契丹帝国传奇. Beijing [北京], Zhongguo guo ji guang bo chu ban she [Chinese International Broadcasting Press] 中国国际广播出版社.

- ^ Liu, Zhanwu [刘占武] and Ren Xuefang [任雪芳] (2007). Sui Tang wu dai da shi ben mo [Major Events of the Sui, Tang, and Wudai Dynasties] 隋唐五代大事本末. Beijing [北京], Zhongguo guo ji guang bo chu ban she [China International Broadcasting Press] 中国国际广播出版社.

- ^ Fei, Xiaotong [费孝通] (1999). Zhonghua min zu duo yuan yi ti ge ju [The Framework of Diversity in Unity of the Chinese Nationality] 中华民族多元一体格局. Beijing [北京], Zhongyang min zu da xue chu ban she [Central Nationalities University Press] 中央民族大学出版社. p. 176.

- ^ Zhang, Jiuhe [张久和] (1998). Yuan Menggu ren de li shi: Shiwei--Dada yan jiu [History of the Original Mongols: research on Shiwei-Dadan] 原蒙古人的历史: 室韦--达怛研究. Beijing [北京], Gao deng jiao yu chu ban she [High Education Press] 高等教育出版社. pp. 27–28.