Pseudoprepotherium

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (September 2022) |

| Pseudoprepotherium | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Mylodontidae |

| Genus: | †Pseudoprepotherium Hofstetter, 1961 |

| Type species | |

| †Pseudoprepotherium venezuelanum Hofstetter, 1961

| |

| Other species | |

| |

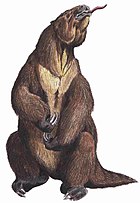

Pseudoprepotherium[1] is an extinct genus of sloths in the family Mylodontidae. It was widespread across northern South America during the Middle and Upper Miocene around 21 to 5.3 million years ago. Fossil finds are known from Brazil Venezuela and Peru. Pseudoprepotherium lived in a tropical climate with a water-rich environment. The remains are limited to limb bones, with the exception of a few skulls and teeth. Based on this, it is a medium to large-sized mylodontid. The genus was described in 1961 and currently contains three species, which were originally assigned to different genera.[2]

Description

Pseudoprepotherium is a medium to large sized member of the family Mylodontidae. The material documented so far consists mainly of limb bones, but also includes individual skulls and remains of jaws. A body weight of around 550 kg is reconstructed for the smaller relatives using a thigh bone around 42 cm long. Large molds with femur lengths of 56 to 59 cm are estimated to have weighed between 1.52 and 1.86 tons[3] A surviving skull has a length of 43 cm, but is partly more deformed laterally, which means that only a few features are recognizable. A clearly bent profile line was characteristic. Because of this, the rostrum and the cranium were at an angle of 130° to each other. At the occipital bone , the articular processes for the cervical spine protruded with little prominence. The alveoli of the five teeth per row of teeth typical of mylodonts can be seen on the upper jaw, but the two front ones are poorly preserved. From the alveoli it can be seen that the rearmost tooth was the smallest and possibly had two lobes (bilobat). The fourth and third teeth were each elongated.[4]

As is usual in the Mylodontidae, the femur stood out due to its flat, board-like shape in front and behind. The shaft was slightly curved at the side. There was only a shallow indentation between the spherical condyle and the greater trochanter. The great calculus was massive but not very elevated. Its apex was at or slightly below the level of the condyle, and thus lower as compared to Magdalenabradys. The lesser trochanter was only weakly developed. The third trochanter appeared as a slight bulge around the middle of the shaft, and continued as an edge to the lower end of the joint. The position roughly matched that of Magdalenabradys, but was lower than that of Eionaletherium. The lower end of the joint was partially rotated out of the shaft axis. The inner articulated roller became larger than the outer. Compared to the upper end of the joint, the lower one was somewhat narrower. A tibia associated with a femur about 56 cm long measured 29 cm in length. This corresponds to the ratio known in other mylodonts of extremely short lower sections of the hindlimbs compared to the upper ones. As a result, the tibia was only half the length of the femur. The proportions are broadly similar to Lestodon, while Glossotherium possessed even shorter lower leg sections. The shaft of the tibia narrowed sharply in the middle, while the ends of the joints protruded far.[4][5]

Paleobiology

Due to its far northern distribution in South America, Pseudoprepotherium was probably more adapted to tropical climate conditions. The find locations in the deposit units of the Urumaco sequence also speak in favor of this. A possibly related Pseudoprepotherium tibia from the Middle Miocene Pebas Formation near Iquitos in the western Amazon Basin, about 23 cm long, shows more than 60 bite marks, the size and arrangement of which are probably from a juvenile Purussaurus had been caused. The size of the bite marks, from three to 15 mm in diameter, allows the length of the attacker to be reconstructed to be around four m. It caught its prey with its front teeth. Attacks on the hind legs are also known from modern crocodiles.[6]

Classification

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Pseudoprepotherium is a member of the Mylodontidae family, within the suborder (Folivora). The Mylodontidae, in turn, are often placed together with the Scelidotheriidae in the superfamily of the Mylodontoidea.[7] In a classic system based on skeletal anatomical features, the Mylodontoidea form a sister group to the Megatherioidea and thus one of the two major lineages of sloths. Molecular genetic analyzes and protein studies also differentiate a third large lineage with the Megalocnoidea . According to the results of the latter two analysis methods, the Mylodontoidea with the two-toed sloths (Choloepus) also include one of the two sloth genera that still exist today.[8][9] The Mylodontidae form one of the most diverse groups within the sloths. Characteristic features can be found in the high-crowned teeth, which, unlike those of the Megatherioidea and Megalocnoidea, have a rather flat ( lobate) possess chewing surface. This particular tooth structure is widely thought to reflect a greater adaptation to grassy diets. The posterior teeth are round, oval or more complex in cross-section and correspond to molar-like teeth. The foremost tooth is designed like a canine. The rear foot also clearly shows twists so that the sole points inwards. The mylodonts can be detected for the first time in the Oligocene , one of the earliest forms is Paroctodontotherium from Salla-Luribay in Bolivia.

The internal organization of the Mylodontidae is complex and currently under discussion. A relatively wide recognition usually only find the late development lines with the Mylodontinae and Lestodontinae , as several studies have shown since 2004, but they are sometimes also discussed negatively. Other lineages associated with the Nematheriinae, the Octomylodontinae, or the Urumacotheriinae, depending on the author, however, are more controversial. The latter in particular summarize the late Miocene representatives of northern South America. In principle, many researchers urge a revision for the entire family, since many of the higher taxonomic units have no formal diagnosis. The position of Pseudoprepotherium within the Mylodontidae is therefore ambiguous, since the genus is largely defined by the limb bones. Based on their characteristics, phylogenetic analyzes indicate that Pseudoprepotherium is more closely related to some more modern representatives, such as Thinobadistes, a form widely found in Central and North America. However, the limb bones usually only offer a limited selection of features for determining family relationships. Investigations on the little skull material therefore see Pseudoprepotherium clearly more basally embedded in the mylodonts and move the form partly closer to Urumacotherium , but also to the Scelidotheriidae.

The term Pseudoprepotherium was scientifically introduced in 1961 by Robert Hoffstetter . He mentioned them in a publication of a skeletal description of Planops , a member of the Megatheriidae from the Santa Cruz Formation of the Early and Middle Miocene of Patagonia . He also referred to the genus Prepotherium , which also occurs there and is closely related . Both had already been described by Florentino Ameghino at the end of the 19th century using finds from the Santa Cruz Formation . In 1934, R. Lee Collins referred a femur from the Río Yuca Formation on the Río Tucupido near Guanare in the Venezuelan state of Portuguesa to Prepotherium and set up with it the new species Prepotherium venezuelanum . In 1961, Hoffstetter classified this femur as part of the Prepotherium genus on the basis of anatomical differences and established a new one with Pseudoprepotherium . At first he saw their systematic position as ambiguous. In 1985, Sue Hirschfeld moved Pseudoprepotherium to the Mylodontidae. Their assessment was based on extensive finds from the important Middle Miocene fossil site of La Venta in Colombia in connection with Collins' thigh find. In hindsight, Hirschfeld's characterization diagnosis turned out to be incorrect, since Collins' find from the Río Yuca Formation and the La Venta material are from today's perspective assigned to different genera, but their assessment of the position of Pseudoprepotherium is based on the characteristics of the femur divided until today.

A total of three species of Pseudoprepotherium are currently considered to be valid today:

- P. socorrensis (Carlini , Scillato-Yané & Sánchez , 2006)

- P. urumaquensis ( Carlini, Scillato-Yané & Sánchez , 2006)

- P. venezuelanum ( Collins , 1934)

P. venezuelanum is the type species and the smallest representative with a femur length of around 42 cm. It is based on the form introduced by R. Lee Collins in 1934 as Prepotherium venezuelanum . The other two species, which are significantly larger with femur lengths of 56 to 59 cm, were recognized in 2006 by a work team led by Alfredo A. Carlini, but were originally included in the genus Mirandabradys . Carlini and colleagues had defined this using numerous finds from the Urumaco sequence in the Falcón Basin of north-western Venezuela, the chronological range of which includes the Middle and Upper Miocene . However, a 2020 revision of the fossil remains by Ascanio D. Rincón and H. Gregory McDonald led to the dissolution of the genus and a relegation to the genus Pseudoprepotherium , largely based on the design of the femur. A third species, named Mirandabradys zabasi by Carlini et al. also from the Urumaco sequence, is considered a nomen dubium because its femur does not show the corresponding diagnostic features of Mirandabradys or Pseudoprepotherium (a femur of Mirandabradys zabasi was originally assigned to the giant Lestodon, which did not occur in northern South America; Carlini et al. 2006 simultaneously removed the femur of Mirandabradys zabasi and reassigned the rest, a skull, to Bolivartherium, to which they attributed further skeletal material; Rincón and McDonald in turn kept only the skull at Bolivartherium in 2020 and split off Magdalenabradys based on the postcranial skeletal elements ). As early as 1985, Sue Hirschfeld named the species Pseudoprepotherium confusum. A skull and several limb bones from La Venta formed the basis for this. Referring to deviations in the structure of the femur, Rincón and McDonald reclassified the 2020 form as the type species of the new genus Magdalenabradys.

Paleoecology

So far, Pseudoprepotherium has only been found in the northern part of South America. The genus defining fossil remains came to Taqe in the Río Yuca Formation on the Río Tucupido about 11 km west-southwest of Guanare in the Venezuelan state of Portuguesa. It is a femur that was found in the first third of the 20th century. The site was then inaccessible for a long time, since it was created during the construction of a reservoir (the Virgen de la Coromoto reservoir) sank. However, a new fossil locality on the eastern shore of the lake largely corresponds spatially and temporally to the original site. This was announced in a publication in 2016. The site contained a small collection of vertebrates , such as remains of fish and crocodilians; such as Purussaurus, as well as armored Peltephilidae and South American ungulates. The Río Yuca Formation is composed largely of limestone and sandstone with discrete interstices of conglomerate. It originated in a freshwater environment with a formation period possibly in the Middle and Late Miocene.[3][5]

The most extensive fossil material to date belongs to the Urumaco sequence , a complex depositional unit that is predominantly exposed in the approximately 36,000 km² large Falcón Basin in the Venezuelan state of Falcón . It is composed of the lithostratigraphic units of the Socorro, Urumaco and Codore Formations, with remains of Pseudoprepotherium being limited to the two lower and first-mentioned sequences. The Urumaco sequence covers the period from the Middle Miocene to the Early Pliocene. The main components are different layers of sand, clay and/silt and limestone in which individual coal seams are embedded, at least in the Urumaco Formation. The rock strata were formed in what was originally a coastal area under the influence of a river delta.[10] From the entire Urumaco sequence, a large number of sites are documented, the exploration of which began as early as the 1950s. They are distributed over a good 60 different stratigraphic levels. The find material consists mainly of fish, especially sharks and rays. In addition, there are also reptiles such as turtles, crocodilians and isolated snakes, as well as mammals appearing with rodents, South American ungulates, manatees, and minor jointed animals among others. The secondary articulated animals show a high diversity, which almost reaches that of the contemporary fauna of southern South America in the Pampas region or in Mesopotamia. Armadillos, the Pampatheriidae and Glyptodontinae as well as sloths have been proven.[11][12][13] Mainly in the late 20th and early 21st century, numerous new forms were described, such as Urumacocnus and Pattersonocnus from the family Megalonychidae, Urumaquia and Proeremotherium as representatives of the large Megatheriidae and Magdalenabradys, Bolivartherium, Eionaletherium and Urumacotherium from the lineage Mylodontidae and their immediate relatives. As a special circumstance of taphonomy , the frequent tradition of limb elements in sloths is to be evaluated, however, from Pseudoprepotherium also documented remains of the skull.[14][4][15][5]

Finds possibly related to Pseudoprepotherium come from the western Amazon basin and also date to the Middle to Upper Miocene. They are part of a large number of fossil remains from numerous local sites spread over a large area. Significant find areas are on the Río Sepa and the Río Inuya , which flow into the Río Urubamba in central Peru . From here, the find area extends eastward to western Brazil and northern Bolivia , and northward to the Iquitos region of northern Peru. The found material belongs to the Ipururo and Pebas formations. These go back to a phase when the so-called "Proto-Amazon" existed, a landscape characterized by lakes, swamps and rivers with connections to the Caribbean. It can now be described as "the Pebas mega wetland". Some of the finds, however, are assigned to the species Pseudoprepotherium confusum,[16][17][18] which is now considered the type form of the genus Magdalenabradys.[5] Other Pseudoprepotherium finds from the region belong to the transition to the Upper Miocene and include a mandible. At the same time, the Pebas mega wetland also includes the related Urumaquia and Megathericulus from the Megatheriidae family.[14]

References

- ^ "Pseudoprepotherium Hoffstetter, 1961". www.gbif.org. GBIF. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Pseudoprepotherium". www.fossilworks.org. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ a b Rincón, Ascanio D.; Solórzano, Andrés; Macsotay, Oliver; McDonald, H. Gregory; Núñez-Flores, Mónica (2016). "A new Miocene vertebrate assemblage from the Río Yuca Formation (Venezuela) and the northernmost record of typical Miocene mammals of high latitude (Patagonian) affinities in South America". Geobios. 49 (5): 395–405. ISSN 0016-6995.

- ^ a b c Carlini, Alfredo A.; Scillato‐Yané, Gustavo J.; Sánchez, Rodolfo (2006-01-01). "New Mylodontoidea (Xenarthra, Phyllophaga) from the Middle Miocene‐Pliocene of Venezuela". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (3): 255–267. doi:10.1017/S147720190600191X. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ a b c d Rincón, Ascanio D.; McDonald, H. Gregory (2020-08-07). "Reexamination of the Relationship of Pseudoprepotherium hoffstetter, 1961, to the Mylodont Ground Sloths (Xenarthra) from the Miocene of Northern South America". Revista Geológica de América Central (63). ISSN 2215-261X.

- ^ Pujos, François; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo (2020-08-26). "Predation of the giant Miocene caiman Purussaurus on a mylodontid ground sloth in the wetlands of proto-Amazonia". Biology Letters. 16 (8): 20200239. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2020.0239. PMC 7480153. PMID 32842894.

- ^ Varela, Luciano; Tambusso, P Sebastián; McDonald, H Gregory; Fariña, Richard A (2018-09-15). "Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis". Systematic Biology. 68 (2): 204–218. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy058. ISSN 1063-5157.

- ^ Delsuc, Frédéric; Kuch, Melanie; Gibb, Gillian C.; Karpinski, Emil; Hackenberger, Dirk; Szpak, Paul; Martínez, Jorge G.; Mead, Jim I.; McDonald, H. Gregory; MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Billet, Guillaume (2019-06-17). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 31178321.

- ^ Presslee, Samantha; Slater, Graham J.; Pujos, François; Forasiepi, Analía M.; Fischer, Roman; Molloy, Kelly; Mackie, Meaghan; Olsen, Jesper V.; Kramarz, Alejandro; Taglioretti, Matías; Scaglia, Fernando (July 2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. ISSN 2397-334X.

- ^ Luis I. Quiroz und Carlos A. Jaramillo: Stratigraphy and sedimentary environments of Miocene shallow to marginal marine deposits in theUrumaco trough,Falcón Basin, Western Venezuela. In: Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, Orangel A. Aguilera und Alfredo A. Carlini (Hrsg.): Urumaco and Venezuelan palaeontology, the fossil record of the northern Neotropics. Indiana University Press 2010, S. 153–172

- ^ Czerwonogora, Ada. Morfología sistemática y paleobiología de los perezosos gigantes del género Lestodon Gervais 1855 (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada) (Thesis). Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

- ^ Sánchez‐Villagra, Marcelo R.; Aguilera, Orangel A. (January 2006). "Neogene vertebrates from Urumaco, Falcón State, Venezuela: Diversity and significance". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (3): 213–220. doi:10.1017/s1477201906001829. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Hastings, Alexander K. (2012-06-14). "The Incredible Fossils of Urumaco and Beyond: Exploring Venezuela's Geologic Past". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20 (2): 147–148. doi:10.1007/s10914-012-9208-z. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ a b Carlini, Alfredo A.; Brandoni, Diego; Sánchez, Rodolfo (2006). "First Megatheriines (Xenarthra, Phyllophaga, Megatheriidae) from the Urumaco (Late Miocene) and Codore (Pliocene) Formations, Estado Falcón, Venezuela". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (3): 269–278. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Rincón, Ascanio D.; Solórzano, Andrés; McDonald, H. Gregory; Montellano-Ballesteros, Marisol (2019-03-04). "Two new megalonychid sloths (Mammalia: Xenarthra) from the Urumaco Formation (late Miocene), and their phylogenetic affinities". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (5): 409–421. doi:10.1080/14772019.2018.1427639. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Tejada-Lara, Julia V.; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Pujos, François; Baby, Patrice; Benammi, Mouloud; Brusset, Stéphane; De Franceschi, Dario; Espurt, Nicolas; Urbina, Mario; Antoine, Pierre-Olivier (March 2015). Goswami, Anjali (ed.). "Life in proto-Amazonia: Middle Miocene mammals from the Fitzcarrald Arch (Peruvian Amazonia)". Palaeontology. 58 (2): 341–378. doi:10.1111/pala.12147.

- ^ Antoine, Pierre Olivier; Abello, María Alejandra; Adnet, Sylvain; Altamirano Sierra, Ali J.; Baby, Patrice; Billet, Guillaume; Boivin, Myriam; Calderón, Ysabel; Candela, Adriana Magdalena; Chabain, Jules; Corfu, Fernando (2016). "A 60-million-year Cenozoic history of western Amazonian ecosystems in Contamana, eastern Peru". Gondwana Research. 31. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2015.11.001. ISSN 1342-937X.

- ^ Antoine, Pierre-Olivier; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Pujos, François; Ganerød, Morgan; Marivaux, Laurent (2017-03-01). "Western Amazonia as a Hotspot of Mammalian Biodiversity Throughout the Cenozoic". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 24 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9333-1. ISSN 1573-7055.

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from September 2022

- Prehistoric sloths

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Miocene xenarthrans

- Miocene mammals of South America

- Fossil taxa described in 1961

- Taxa named by Robert Hoffstetter

- Neogene Venezuela

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Neogene Peru

- Fossils of Peru

- Neogene Brazil

- Fossils of Brazil