Benjamin Robbins Curtis: Difference between revisions

7&6=thirteen (talk | contribs) m →Published works: [http://books.google.com/books?id=dBc8AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Benjamin+Curtis+Reports+of+Cases+in+the+Circuit+Courts+of+the+United+States&source=bl&ots=aTPq0RCU16&sig=dy0 |

m clarifying |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

'''Benjamin Robbins Curtis''' (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an [[United States|American]] [[Lawyer|attorney]] and [[Supreme Court of the United States|United States Supreme Court]] Justice. |

'''Benjamin Robbins Curtis''' (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an [[United States|American]] [[Lawyer|attorney]] and [[Supreme Court of the United States|United States Supreme Court]] Justice. |

||

He was the first |

He was the first justice of the Supreme Court to have a formal legal degree and the only justice to have resigned from the court over a matter of principle. He successfully acted as chief counsel for President Andrew Johnson during the first presidential impeachment trial. |

||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

Benjamin Curtis was born November 4, 1809 in [[Watertown, Massachusetts]], the son of Lois Ribbins and Benjamin Curtis |

Benjamin Curtis was born November 4, 1809 in [[Watertown, Massachusetts]], the son of Lois Ribbins and Benjamin Curtis, the captain of a [[merchant vessel]]. Young Curtis attended common school in [[Newton, Massachusetts|Newton]] and beginning in 1825 [[Harvard University|Harvard College]], where he won an essay writing contest in his junior year. He graduated in 1829, a member of [[Phi Beta Kappa]].<ref>[http://www.pbk.org/userfiles/file/Famous%20Members/PBKSupremeCourtJustices.pdf Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members], Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed Oct 4, 2009</ref> He subsequently graduated from [[Harvard Law School]] in 1831 and was admitted to the bar the following year. |

||

In 1834, he moved to Boston where he joined the law firm of Charles P Curtis Esquire. |

In 1834, he moved to Boston where he joined the law firm of Charles P Curtis Esquire. He became a [[Harvard Fellow]] in February of 1846. Three years later, "he was elected to the [[Massachusetts State Legislature]]. He was appointed chairman of a committee charged with the reform of state judicial procedures, and within two years presented the [[Massachusetts Practice Act of 1851]]. It was considered a model of judicial reform and was approved by the legislature without amendment."<ref>[http://www.supremecourthistory.org/history/supremecourthistory_history_assoc_027curtis.htm Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Timeline of the Court,] [[Supreme Court Historical Society]].</ref> |

||

At the time, he was viewed as a rival to [[Rufus Choate]], and was thought to be the preeminent leader of the [[New England]] bar. He came from a politically-connected family, and had studied under [[Joseph Story]] and [[John Hooker Ashmun]]<ref name="NYT">[http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9E03E1D9103EE73BBC4152DFB6678382669FDE New Publications, ''Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis'',(October 19, 1879).] [[New York Times]]</ref> at Harvard Law School. His legal arguments were thought to be well-reasoned and persuasive. He was a [[Whig]] and in tune with their politics, and Whigs were in power. As a potential young appointee, he was thought to be the seed of a long and productive judicial career. He was appointed by the president, approved by the Senate, elevated to the bench, and was unexpectedly gone in six years.<ref>[http://www.jstor.org/stable/362583 Leach, Richard H. ''Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit''. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.]</ref> |

At the time, he was viewed as a rival to [[Rufus Choate]], and was thought to be the preeminent leader of the [[New England]] bar. He came from a politically-connected family, and had studied under [[Joseph Story]] and [[John Hooker Ashmun]]<ref name="NYT">[http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9E03E1D9103EE73BBC4152DFB6678382669FDE New Publications, ''Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis'',(October 19, 1879).] [[New York Times]]</ref> at Harvard Law School. His legal arguments were thought to be well-reasoned and persuasive. He was a [[Whig]] and in tune with their politics, and Whigs were in power. As a potential young appointee, he was thought to be the seed of a long and productive judicial career. He was appointed by the president, approved by the Senate, elevated to the bench, and was unexpectedly gone in six years.<ref>[http://www.jstor.org/stable/362583 Leach, Richard H. ''Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit''. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:56, 2 April 2010

Benjamin Robbins Curtis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court | |

| In office September 22, 1851[1] – September 30, 1857 | |

| Nominated by | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Levi Woodbury |

| Succeeded by | Nathan Clifford |

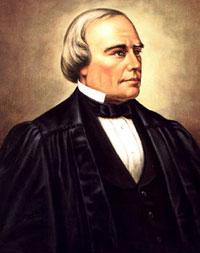

Benjamin Robbins Curtis (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an American attorney and United States Supreme Court Justice.

He was the first justice of the Supreme Court to have a formal legal degree and the only justice to have resigned from the court over a matter of principle. He successfully acted as chief counsel for President Andrew Johnson during the first presidential impeachment trial.

Biography

Benjamin Curtis was born November 4, 1809 in Watertown, Massachusetts, the son of Lois Ribbins and Benjamin Curtis, the captain of a merchant vessel. Young Curtis attended common school in Newton and beginning in 1825 Harvard College, where he won an essay writing contest in his junior year. He graduated in 1829, a member of Phi Beta Kappa.[2] He subsequently graduated from Harvard Law School in 1831 and was admitted to the bar the following year.

In 1834, he moved to Boston where he joined the law firm of Charles P Curtis Esquire. He became a Harvard Fellow in February of 1846. Three years later, "he was elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature. He was appointed chairman of a committee charged with the reform of state judicial procedures, and within two years presented the Massachusetts Practice Act of 1851. It was considered a model of judicial reform and was approved by the legislature without amendment."[3]

At the time, he was viewed as a rival to Rufus Choate, and was thought to be the preeminent leader of the New England bar. He came from a politically-connected family, and had studied under Joseph Story and John Hooker Ashmun[4] at Harvard Law School. His legal arguments were thought to be well-reasoned and persuasive. He was a Whig and in tune with their politics, and Whigs were in power. As a potential young appointee, he was thought to be the seed of a long and productive judicial career. He was appointed by the president, approved by the Senate, elevated to the bench, and was unexpectedly gone in six years.[5]

Supreme court service

Curtis was appointed to the Supreme Court on 22 September 1851 by President Millard Fillmore. His primary sponsor was Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, who persuaded Filmore to nominate Curtis to the Supreme Court.[6]

He was the first Supreme Court Justice to have actually received a law degree — his predecessors had either "read law" (a form of apprenticeship) or had attended a law school without receiving a degree.[6][7]

His opinion in Cooley v. Board of Wardens 53 U.S. 299 (1852)[8] held that the Commerce Power extends to laws related to pilotage. States laws related to commerce powers can be valid so long as Congress is silent on the matter. This resolved a historic controversy over federal interstate commerce powers. To this day it is an important precedent for resolving disputes.[6] The court interpreted Art. I, section 8, clause 3 of the Constitution, the Commerce Clause, The issue was whether states could regulate aspects of commerce or whether Congress retained exclusive jurisdiction to regulate commerce. Curtis concluded that the federal government enjoyed exclusive power to regulate commerce only when the thing regulated required national uniformity. Otherwise, states were permitted to regulate commerce.[7]

He was notable as one of the two dissenters in the Dred Scott case, where he disagreed with virtually every holding of the court, and argued against the majority's denial of the slave Scott's bid for emancipation. See, dissenting opinion of Justice Benjamin Curtis, wherein he stated that there were African American citizens in both Southern and Northern at the time: Therefore, they were among the "people of the United States" whom the Constitution addressed. Curtis also opined that since the majority ruled Scott lacked standing before the Court, the Court lacked any right to issue a decision.[6]

Curtis resigned in 1857 from the court because of the bitter feelings engendered by the case.[9][7] It has also been said that his bitterness over the decision was admixed with displeasure over the adequacy of his salary.[10]

Others view the cause of his resignation as being temperamental and financial. He did not like "riding the circuit" as Supreme Circuit Justices were then required to do. He was temperamentally estranged from the court, and was not inclined to work with others -- he was not a 'team player', at least not on that team. The acrimony over the Dred Scott decision had blossomed into mutual distrust. And he could not live on $6,500 per year, which paled in comparison to his earnings in private practice. Finally, the public outcry over his decision was contrary to his elitist inclinations, as the elite was supposed to lead, and the public was not supposed to talk back.[11][12][13]

Yet another source states flatly that “a bitter disagreement and coercion by Roger Taney prompted Benjamin Curtis's departure from the Court in 1857."[14]

"Although he remained on the Court for only six years, Curtis is generally considered to have been the only outstanding justice on the Taney Court in its later years, other than Taney himself."[6]

He is the only Justice of the Supreme Court to have resigned on a matter of principle.[6]

Life after resignation

Upon his resignation, he returned to his Boston law practice, becoming a "leading lawyer" in the nation. During the ensuing decade and a half, he argued several cases before the Supreme Court.[4]

In 1868, he acted as chief counsel for President Andrew Johnson during the impeachment trial. He himself read the answer to the articles of impeachment, and it was "largely his work." His opening statement lasted two days, and was commended for legal presience and clarity.[4][15] He successfully persuaded the Senate that an impeachment was a judicial act, not a political act, so that it required a full hearing of evidence. This precedent "influenced every subsequent impeachment."[6][7]

After the impeachment trial, he declined President Johnson's offer of the position of U.S. Attorney General.[4]

He was a highly-recommended candidate for the Chief Justice position upon the death of Salmon P. Chase, but was not given the appointment.[4]

He was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for U. S. senator in 1874.[15] In that year, his aggregate professional income was $650,000.[4]

Death and legacy

His daughter, Annie Wroe Scollay Curtis, married December 9, 1880 future Columbia University President and New York Mayor, Seth Low.[16] They had no children.

His remains are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, 580 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts.[17][18][19]

Published works

- Reports of Cases in the Circuit Courts of the United States (2 vols., Boston, 1854)

- Judge Curtis's Edition of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States, with notes and a digest (22 vols., Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1855).

- Digest of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States from the origin of the court to 1854 Little Brown & Co., (1864).

- Memoir and Writings (2 vols., Boston, 1880), the first volume including a memoir by George Ticknor Curtis, and the second "Miscellaneous Writings," edited by Benjamin R. Curtis, his son.[15][4]

References

- ^ "Federal Judicial Center: Benjamin Robbins Curtis". 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed Oct 4, 2009

- ^ Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Timeline of the Court, Supreme Court Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d e f g New Publications, Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis,(October 19, 1879). New York Times

- ^ Leach, Richard H. Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fox, John, The First Hundred Years: Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis. Public Broadcasting Service.

- ^ a b c d Ariens, Michael, Benjamin Curtis.

- ^ Cornell Law School, full text of Cooley v. Board of Wardens 53 U.S. 299 (1852).

- ^ Ariens, Michael, Roger B. Taney.

- ^ Oyez.org Official Supreme Court Media, Benjamin Robbins Curtis.

- ^ Friedman, Leon, and Fred L. Israel, eds. The Justices of the Supreme Court, 1789–1969: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Vol II. 1969. pp. 904–05.

- ^ Dickerman, Albert. The Business of the Federal Courts and the Salaries of the Judges. 24 American Law Review 1 (Jan.–Feb. 1890). p. 86.

- ^ Van Tassel, Emily Field; Wirtz, Beverly Hudson; & Wonders, Peter, Why Judges Resign: Influences on Federal Judicial Service,1789 to 1992. pp. 13, 66, 123, 130. National Commission on Judicial Discipline and Removal. Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ Vining Jr., Richard L.; Smelcer, Susan Navarro; Zorn, Christopher J.Emory Judicial Tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court, 1790-1868: Frustration, Resignation, and Expiration on the Bench January 26, 2010 Public Law Research Paper No. 06-10 pp. 9, 10.

- ^ a b c Wilson, James Grant. Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Appletons Encyclopedia

- ^ "Seth Low" by Gerald Kurland, New York, Twayne Publishers, 1971

- ^ Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- ^ Benjamin Robbins Curtis memorial at Find a Grave.

- ^ Christensen, George A., Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited, Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17 - 41 (Feb 19, 2008), University of Alabama.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1568021267.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791013774.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195058356.

- Huebner, Timothy S.; Renstrom, Peter; coeditor. (2003) The Taney Court, Justice Rulings and Legacy. City: ABC-Clio Inc.ISBN 1576073688.

- Leach, Richard H. Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.

- Leach, Richard H. Benjamin R. Curtis: Case Study of a Supreme Court Justice (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1951).

- Lewis, Walker (1965). Without Fear or Favor: A Biography of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Martin, Fenton S. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0871875543.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Simon, James F. (2006) Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers (Paperback) New York: Simon & Schuster, 336 pages. ISBN 0743298462.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0815311761.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Dual federalism

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- Origins of the American Civil War

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Taney Court

External links

- Benjamin Robbins Curtis at Find A Grave

- Fox, John, 'The First Hundred Years, Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis. Public Broadcasting Service.

- New Publications, Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis, (October 19, 1879). New York Times.

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1851–1852 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1853–1857 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition