Cricket bat: Difference between revisions

m Fixing my fix |

Darrellw100 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

*[http://www.getahundred.com/blog/archives/1184 video of handmade Cricket bat] |

*[http://www.getahundred.com/blog/archives/1184 video of handmade Cricket bat] |

||

*[http://www.rfs.org.uk/learning/cricket-bat-willows Growing Willow for bats] |

*[http://www.rfs.org.uk/learning/cricket-bat-willows Growing Willow for bats] |

||

*[http://www.stonehousehistorygroup.org.uk/page59.html Old Willow Farm growing Cricket bats in Stonehouse Glos] |

|||

{{Cricket equipment}} |

{{Cricket equipment}} |

||

Revision as of 14:16, 22 August 2011

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

A cricket bat is a specialised piece of equipment used by batsmen in the sport of cricket to hit the ball. It is usually made of willow wood. Its use is first mentioned in 1624.

The blade of a cricket bat is a wooden block that is generally flat on the stiking face and with a ridge on the reverse (back) which concentrates wood in the middle where the ball is generally hit. The blade is connected to a long cylindrical cane handle, similar to that of a tennis racquet, by means of a splice. The edges of the blade closest to the handle are known as the shoulders of the bat, and the bottom of the blade is known as the toe of the bat.

The bat is traditionally made from willow wood, specifically from a variety of White Willow called Cricket Bat Willow, (Salix alba var. caerulea), treated with raw (unboiled) linseed oil. The oil has a protective function. This wood is used as it is very tough and shock-resistant, not being significantly dented nor splintering on the impact of a cricket ball at high speed, while also being light in weight. It incorporates a wooden spring design where the handle meets the blade. The current design of a cane handle spliced into a willow blade was the invention in the 1880s of Charles Richardson, a pupil of Brunel and the chief engineer of the Severn railway tunnel.[1]

Law 6 of the Laws of Cricket,[2] as the rules of the game are known, limit the size of the bat to not more than 38 in (965 mm) long and the blade may not be more than 4.25 in (108 mm) wide. Bats typically weigh from 2 lb 7 oz to 3 lb (1.1 to 1.4 kg) though there is no standard. The handle is usually covered with a rubber grip and the face of the bat may have a protective film. Appendix E of the Laws of Cricket set out more precise specifications.[3] Modern bats are usually hand made in India or Pakistan due to the very low cost of labour, however a few specialists (6 in England, 2 in Australia and 1 in New Zealand) still make bats, mostly with use of a CNC lathe such as Gunn & Moore and Newbery. The art of hand-making cricket bats is known as podshaving.

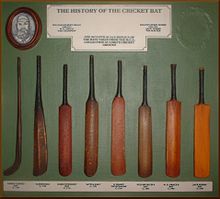

Bats were not always this shape. Before the 18th century bats tended to be shaped similarly to a modern hockey sticks. This may well have been a legacy of the game's reputed origins. Although the first forms of cricket are lost in the mists of time, it may be that the game was first played using shepherds' crooks.

Until the rules of cricket were formalised in the 19th century, the game usually had lower stumps, the ball was bowled underarm (a style of bowling which has since fallen out of common practice and is now in most cases illegal), and batsmen did not wear protective pads.[citation needed] As the game changed, so it was found that a differently shaped bat was better.[citation needed] The bat generally recognised as the oldest bat still in existence is dated 1729 and is on display in the Sandham Room at the Oval in London.[citation needed]

Maintenance

When first purchased most bats are not ready for immediate use and require knocking-in in order to allow the soft fibres to strike a hard new cricket ball without causing damage to the bat and allowing full power to be transferred to the shot. This involves striking the surface with an old cricket ball or a special hammer mallet. This compacts the soft fibres within the bat and reduces the risk of the bat snapping.[4]

Variations/technology of the cricket bat

Various companies have over the years tried new shapes that come within the laws of the game to make a name for themselves and improve sales, in the 60's the first shoulderless bats appeared from Slazenger, in the 70's saw double sided bats from Warsop Stebbing.

In 1974 the first GN100 Scoop was released, the first bat to turn shaping on its head by removing the wood from the centre of the rear of the bat, this quickly became a big seller and various scooped bats such as the GN500, Dynadrive and Viper have been released from Gray Nicolls ever since including a re-release of the Scoop itself for the 2012 English season. The removal of wood from the rear has been copied by many other companies without much critical acclaim.

In 1979 Australian cricketer Dennis Lillee briefly used an ComBat aluminium metal bat. After some discussion with the umpires, and after complaints by the English team that it was damaging the ball, he was urged by the Australian captain Greg Chappell to revert to a wooden bat.[5] The rules of cricket were shortly thereafter amended, stating that the blade of a bat must be made solely of wood.[2]

In 2004 Newbery created the Uzi with a truncated blade and elongated handle for the new T20 format of the game, this was to allow more wood to be placed in the middle as more attacking shots are played in a shorter version of the game.

In 2005 Kookaburra released a new type of bat that a Carbon fiber-reinforced polymer support down the spine of the bat. It was put on the bat to provide more support to the spine and blade of the bat, thus prolonging the life of the bat. The first player to use this new bat in international cricket was Australian Ricky Ponting. However this innovation in cricketing technology was controversially banned by the ICC [6] as they were advised by the MCC that it unfairly gave more power in the shot and was unfair in competition as not all players had access to this new technology. But this was not taken lightly by Australian media as Ponting had scored plenty of runs since he started to use his new bat and English reporters blamed this on his new, 'unfair' piece of technology in his bat.

In 2005 Newbery created a carbon fibre handle, the C6 and C6+ which weighed 3 ounces less than a standard laminated cane and rubber handle, it was used by Newbery and Puma for 3 years before the concept was copied by Gray Nicolls with a hollow plastic tube and then the MCC changed the law on materials in handles amid fears that the new technology would lead to an increase in the distance the ball was hit. Now only 10% of the volume of the handle can be other than cane.

In 2008 Gray-Nicolls launched a bat with a second face on the base of the back of the bat, it was purely a marketing move as no paid players used the bat in competition.[7] In 2011 they also produced a bat with an offset handle position known as The Edge in what is also purely a marketing move.

In 2009 an extreme version of the Newbery Uzi shape was launched by Mongoose, it was named the MMi3 and had a very much shorter blade and longer handle combination than had been seen before. Launched with a fanfare of publicity it proclaimed the idea of not defending the ball in the T20 format and purely playing attacking shots, the firm also produced a standard version bat, CoR3 with a splice hidden in the handle which was marketed as being able to hit sixes from all parts of the blade.

Also in 2009 Black Cat Cricket launched a T20 format bat, the Joker, it worked on a similar principle to other T20 bats with a reduced blade of 2 inches and longer handle but uniquely reduced the width of the bat to 4 inches in an adult bat.

See also

References

- ^ "Severn Tunnel (1)". Track Topics, A GWR Book of Railway Engineering. Great Western Railway. 1935 (repr. 1971). p. 179.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Website by the OTHER media (2008-10-01). "Law 6: Bats". Lords.org. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Website by the OTHER media. "Laws of Cricket Appendix E - The bat". Lords.org. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ "Cricket equipment: Caring for your kit". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "Bat maker defends graphite innovation". BBC Sport. 11 April 2005. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "ICC and Kookaburra Agree to Withdrawal of Carbon Bat". NetComposites. 2006-02-19. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ^ "Twenty20's latest swipe: a bat out of hell". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-15.