Basilica of San Vitale: Difference between revisions

→Further reading: + 1, to be used in refs |

→Legacy: remove section; can find no indication San Vitale inspired Sts. Sergius and Bacchus |

||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

The direction of these mosaics from west to east or towards the apse suggests both the bringing in the Eucharistic elements into the church and their presence as gifts to be offered to Christ above. The appears of the Three Magi or Kings bearing gifts on the hem of Theodora's robes reinforces the latter meaning. The moment represented has been identified liturgically as the Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Symbolically this entrance is understood to mark the First Coming of Christ.<ref>{{cite web|last=Sullivan|first=Mary Ann.|title="San Vitale'"|url=http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/san_vitale.html|accessdate=Accessed March 5, 2012}}</ref> |

The direction of these mosaics from west to east or towards the apse suggests both the bringing in the Eucharistic elements into the church and their presence as gifts to be offered to Christ above. The appears of the Three Magi or Kings bearing gifts on the hem of Theodora's robes reinforces the latter meaning. The moment represented has been identified liturgically as the Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Symbolically this entrance is understood to mark the First Coming of Christ.<ref>{{cite web|last=Sullivan|first=Mary Ann.|title="San Vitale'"|url=http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/san_vitale.html|accessdate=Accessed March 5, 2012}}</ref> |

||

==Legacy== |

|||

The Church of San Vitale is one of a great number of elaborate churches built during the Middle Ages. Its concept and design inspired the designs of several other churches commissioned by various leaders in different regions of western Europe. These include the Church of [[Saints Sergius and Bacchus (Istanbul)|Saints Sergius and Bacchus]] in [[Constantinople]], which in turn became the model used by [[Charlemagne]] for his [[Palatine Chapel in Aachen]] in 805.{{cn|date=April 2012}} |

|||

{{Commons|San Vitale (Ravenna)}} |

{{Commons|San Vitale (Ravenna)}} |

||

Revision as of 16:00, 16 April 2012

| Church of San Vitale | |

|---|---|

The Church of San Vitale | |

| Religion | |

| Region | Emilia-Romagna |

| Year consecrated | 547 |

| Location | |

| Location | |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Byzantine architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 527 |

| Completed | 548 |

| Construction cost | 26,000 solidi (gold pieces) |

The Church of San Vitale — styled an "ecclesiastical basilica" in the Roman Catholic Church, though it is not of architectural basilica form — is a Byzantine church in Ravenna, Italy. Built in the mid-sixth century under sponsorship by the emperor Justinian and his wife Theodora, the unique octagonal building style is one of the most important examples of early Christian Byzantine Art and architecture in western Europe. It also served as a reminder of the Eastern-Roman Byzantine Christian presence in Italy at the time when much of the west was under Arian Ostrogothic rule. The building is one of eight Ravenna structures inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

History

The church was first initiated by Ecclesius, Bishop of Ravenna shortly after a trip to Byzantium with Pope John in 525.[1] Construction of the building itself began in 527, when Ravenna was under the rule of the Ostrogoths. It was completed in 548 after Ravenna was retaken under Byzantium rule, and was consecrated by Maximian the 27th Bishop of Ravenna during the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna.[2] The architects of this church were brought in from Constantinople, which explains the building’s concept representing a Byzantine styled standardized design to function as a palace and baptistery.[3] Unfortunately, the names of the architects remain unknown.

Construction became possible in Ravenna due in part to King Theodoric’s policy of religious freedom, as well as recognition of the Pope’s authority over Rome.[4] This status remained unchanged after Theodoric’s death under the regency of his daughter Amalasuntha, which saw a great weakening of Ostrogothic power. Subsequently, upon her death, much of the kingdom including Ravenna was re-conquered by the Byzantine general Belisarius within a few years.[5]

After Justinian reclaimed Ravenna for the Byzantine Empire, it became the Italian center of his Eastern empire and the focus of his artistic patronage in Italy. Justinian wanted to restore Christendom to the west, ravaged by northern pagans, and this can be seen in his building programs. Ravenna was the site of the development of the aforementioned centrally planned church.[6]

Funding for the church’s construction was sponsored almost entirely by a Greek banker, Julius Argentarius, of whom very little is known except that he was believed to have been a private banker of Ravenna or perhaps a royal envoy of Justinian. He was also responsible for sponsoring the construction of the Basilica of Sant' Apollinare in Classe at around the same time. The final cost of the project is estimated to have amounted to 26,000 solidi (gold pieces).[7]

Architecture

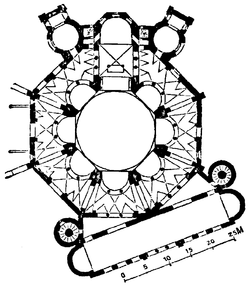

The church is composed of two concentric octagonal prisms. The outer and lowest one contains two levels of galleries, covered by a systems of vaults built in the 12th century.[8] The, inner and highest one climaxes with the dome over the octagonal drum connected to the pillars of the antes octagon by a series of semi-circular arches. They are connected together by the arches delimiting the semi-circular niches(exedrae) on the sides of the inner octagon. The octagons are both covered by timber roofs. The east side opens to the presbyterion and a polygonal apse. Nearly opposite, the main entrance is preceded by a nartex shaped as a forceps and built tangent to one of the sides of the external octagon. Two towers are situated at the two sides of the narthex, one of which were eventually converted to bell towers in the tenth to twelfth centuries.[9]

The arches and polygonal apse represent elements of Roman elements, which also include the shape of doorways, and stepped towers; with Byzantine elements: such as capitals, and narrow bricks. The longitudinal axis of he basilica is forsaken in San Vitale, to create a greater emphasis on heaven above. At first the plan seems unified and simplified, easily read. But this is undermined by the narthex being placed off axis, making the vistas (views) become extremely complex for potential visitors regarding their position to the chancel and the altar.[10] All of the buttressing is done from the exterior, giving an impression that there is little support for the dome's weight and an emphasis of the structure being held by God. [11]

This emphasis on divinty is further shown by the overlay of marble and mosaics on the walls. In addition, these are brilliantly illuminated by the sequence of shifting curved screens of columns in the exedrae, contrasts between dark and lighted areas, with light filtering into the structure via large windows in the ambulatory, and an undulating interior core that soars to the dome above.[12] As a result, the contrast between the plain, brick-filled exterior with the ornate design of the interior is made to represent the transition from the material world into the spiritual plane.[13] This was derived from the belief of light being a medium through which the holy Trinity is represented on earth. The notion is complemented through a spherical dome constructed of clay tubes with a diameter of approximately 16m.[14] As the dome represents the path leading upwards towards heaven, it gives a sense of one being able to directly experience the divine.[15]

It is evident that the construction and design of the San Vitale is the product of very precise masonry. Composed of Julianean bricks and very thick mortar joints, the walls appear to have “evident horizontal stripping,”. The structure seems to be impenetrable due to the walls of the structure being two to three layers thick (Binda). The fine masonry that was practiced in the construction of this basilica may be an explanation as to why the structure is still standing today, with minimal wear.[16]

The church is most famous for its wealth of Byzantine mosaics,[17] the largest and best preserved outside of Constantinople. The church is of extreme importance in Byzantine art, as it is the only major church from the period of the Emperor Justinian I to survive virtually intact to the present day. Furthermore, it is thought to reflect the design of the Byzantine Imperial Palace Audience Chamber, of which nothing at all survives. According to legend, the church was intentionally erected on the site of the martyrdom of Saint Vitalis by order of Justinian.[18] This was to both honour the Christian martyr as well commemorate a return of Christianity to the "Pagan" world. However, there is some confusion as to whether this is the Saint Vitalis of Milan, or the Saint Vitale whose body was discovered together with that of Saint Agricola, by Saint Ambrose in Bologna in 393.

In its octagonal form, the church was understood as a martyrium to San Vitale, as quoted by Von Simson: "Liturgically and mystically, a martyr's sanctuary is both his tomb and Christ's sepulcher; and early Christian theology conceived the dignity of martyrdom as the martyr's mystical transfiguration into Christ. The architecture of San Vitale, evoking this relation of the death and resurrection of the titular saint to the death and resurrection of Christ, is a significant tribute to the Christ-like dignity of St. Vitalis."[19]

Mosaic art

The central section is surrounded by two superposed ambulatories. The upper one, the matrimoneum, was reserved for married women. A series of mosaics in the lunettes above the triforia depict biblical tales of from the Old Testament.[20] These include Jeremiah and Isaiah, representatives of the twelve tribes of Israel, and the story of Abel and Cain. A pair of angels, holding a medallion with a cross, crowns each lunette. On the side walls the corners, next to the mullioned windows, have mosaics of the Four Evangelists, under their symbols (angel, lion, ox and eagle), and dressed in white. Especially the portrayal of the lion is remarkable in its feral ferocity.

The entrance to the Chancel Vault is marked by a Triumphal Arch showing medallions with the Apostles and Gervase and Prothase. Christ appears at the apex or keystone of the arch. The chancel vault has at the center a representation of the Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God, directly above the altar. Christian iconography used the Agnus Dei as an allegorical representation of the "Sacrifice" of Christ. The symbolic link of the Agnus Dei to the altar beneath clearly establishes a vertical axis focusing on the sacrificial symbolism of the Eucharist. See how this symbolism is continued in the flanking north and south walls. The wreath encircling the Lamb can be related to the Triumphal crowns offered to Emperors or Generals to commemorate victories. The Child's Sarcophagus from the end of the fourth century has a comparable crown encircling the chi-rho and being supported by angels. Note that a similar crown is being presented to St. Vitale in the apse mosaic to commemorate his martyrdom. The wreath is supported on four sides by angels standing on orbs. The chancel vault is clearly connected to the tradition of dome architecture referencing monuments like Pantheon constructed by the Emperor Hadrian in the early second century.[21]

The cross-ribbed vault in the presbytery is richly ornamented with mosaic festoons of leaves, fruit and flowers, converging on a crown encircling the Lamb of God. The crown is supported by four angels, and every surface is covered with a profusion of flowers, stars, birds and animals, including many peacocks. The dome carried the traditional symbolism of universality and all-inclusiveness. therefore, the image of the four angels standing on orbs clearly echoes this symbolism with the reference to the four corners of the world.[22] Above the arch, on both sides, two angels hold a disc and beside them a representation of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. They symbolize the human race (Jerusalem representing the Jews, and Bethlehem the Gentiles).

At the top of the wall marking the entrance to the apse appear three windows. Considering the central role the Trinity played in the doctrinal debates of the period, the windows clearly are a Trinitarian reference. As one of the primary sources of light in this interior, these windows carry the traditional light symbolism of the Trinity as equated to the light of the world. This use of triple openings is found regularly at San Vitale.[23] The north and south walls flanking the altar focus principally on Old Testament figures. The lunette on the north wall represents two different episodes in the story of Abraham and Isaac. An example is seen on the center and left hand side of the mosaic, which represents the angels announcing to Abraham the birth of his son Isaac in the book of Genesis.[24] This is followed by the right hand side of this mosaic represents the famous story of the Sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham. The area left of the lunette depicts the Prophet Jeremiah; while the right shows Moses ascending Mt. Sinai with the Twelve Tribes of Israel grouped around Aaron below (right). Moses is shown beardless in all three appearances in the presbytery, like Christ in the apse. The upper level of the left wall has full-length figures of two evangelists and their symbols: John with his eagle (left) and Luke with his ox (right). Below their feet are ducks and other water fowl.[25]

On the South Wall is an explicit depiction of Eucharistic symbolism with an altar bearing bread and wine between the figures of Abel and Melchisedech presenting their offerings. This mosaic conflates two narratives of offering from the book of Genesis. Abel is shown offering the "firstlings of his flock" that is part of the story of the offering of Cain and Abel.[26] The two narratives tell of Cain's jealousy and muder of Abel, while Melchisedech, the priest / king of Salem, offers Abraham bread and wine.

The eastern spandrel on the south wall depict the mission of Moses from the book of Exodus who appears first at the bottom tending the sheep of Jethro, and again above depicting God's call in the Burning Bush to lead the Israelites out of Egypt.[27] Subsequently, the eastern spandrel on the north side represents Moses receiving the Ten Commandments. Further along, the western spandrels on the north and south represent Prophets: Jeremiah and Isaiah respectively. Isaiah prophecies were principally connected with the Incarnation of Christ, while Jeremiah was traditionally seen as the prophet of Christ's Passion. The four evangelist appear on the next level. Each evangelist is associated with one of the corners of the chancel mosaic, and the division between the level shows the break between the Old and New Testaments.[28] As on the other side, the side panels of the upper level depict two evangelists: Matthew (with winged man symbol) and Mark (with lion symbol). They are depicted against a grassy landscape with aquatic creatures, including a heron and a tortoise, beneath their feet.[29]

All these mosaics are executed in the Hellenistic-Roman tradition: lively and imaginative, with rich colors and a certain perspective, and with a vivid depiction of the landscape, plants and birds. They were finished when Ravenna was still under Gothic rule. The apse is flanked by two chapels, the prothesis and the diaconicon, typical for Byzantine architecture.

Inside, the intrados of the great triumphal arch is decorated with fifteen mosaic medallions, depicting Jesus Christ, the twelve Apostles and Saint Gervasius and Saint Protasius, the sons of Saint Vitale. The theophany was begun in 525 under bishop Ecclesius. It has a great gold fascia with twining flowers, birds, and horns of plenty. Jesus Christ appears, seated on a blue globe in the summit of the vault, robed in purple, with his right hand offering the martyr's crown to Saint Vitale. On the left, Bishop Ecclesius offers a model of the church.

Also, in the apse is a mosaic on the left side of which St. Vitalis is shown receiving the crown of martyrdom from a beardless Christ. While on the right side of the mosaic Christ is receiving a model of the church from Bishop Ecclesius.[30]

Justinian and Theodora panels

At the foot of the apse side walls are two famous mosaic panels, executed in 548. On the right is a mosaic depicting the East Roman Emperor Justinian I, clad in purple with a golden halo, standing next to court officials, Bishop Maximian, palatinae guards and deacons. The halo around his head gives him the same aspect as Christ in the dome of the apse. Justinian himself stands in the middle, with soldiers on his right and clergy on his left. Some of the other men hold objects as well, including a censer, an ornate book, and a soldier’s shield displaying Christ’s monogram, the Chi-Rho.[31] This image provides the emphasis of the central position of the Emperor between the power of the church and the power of the imperial administration and military. Just like Roman Emperors of the past, it proclaims that Justinian is the leader of the church, state, and military of his empire.[32] This was appropriate considering his status as one of the most powerful Byzantine Emperors and as well as his revision of Roman law(Corpus Juris Civilis). This image assumed its most important political function when an emperor had just ascended the throne or when he wished to demonstrate his authority even in the remotest parts of the Empire. Whether to legalize the imperial power or to proclaim it, the emperor's portrait was sent out in the most solemn way. When the procession carrying it approached a city, the whole population went out with candles and incense to pay homage to the new ruler. These 'sacred images,' as they were significantly called, were subsequently erected in a public place, an act which furnished the occasion for the declaration of submission on the part of the people.[33]

The gold background of the mosaic shows that Justinian and his entourage are inside the church. The figures are placed in a V shape; Justinian is placed in the front and in the middle to show his importance with Bishop Maximian on his left and lesser individuals being placed behind them. This placement can be seen through the overlapping feet of the individuals present in the mosaic.[34]

Another panel (not pictured) shows Empress Theodora solemn and formal, with golden halo, crown and jewels, and a train of court ladies. She is almost depicted as a goddess. As opposed to the V formation of the figures in the Justinian mosaic, the mosaic with Empress Theodora shows the figures moving from left to right into the church. Theodora is seen holding the wine corresponding to Justinian’s paten. Also, her robe is embroidered with an image of the Three Magi. This indicates in a spiritual sense their the intention to associate themselves, as many Christian rulers have, with the biblical kings who brought gifts to the Christ Child.[35]

The direction of these mosaics from west to east or towards the apse suggests both the bringing in the Eucharistic elements into the church and their presence as gifts to be offered to Christ above. The appears of the Three Magi or Kings bearing gifts on the hem of Theodora's robes reinforces the latter meaning. The moment represented has been identified liturgically as the Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Symbolically this entrance is understood to mark the First Coming of Christ.[36]

See also

- A La Ronde, an 18th century house in Devon, England that is supposedly based on the Basilica.

- List of Roman domes

Notes

- ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Layout,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Layout,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Krautheimer,, Richard (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. p. 95.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Canton,, Norman F. (1994). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: HarperPerennial,. pp. p. 108.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Canton,, Norman F. (1994). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: HarperPerennial,. pp. p. 125.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Ferguson, S. ""Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna,"". Retrieved Accessed March 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kleiner and Mamiya. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, p. 332.

- ^ Binda, L. (1998). "St. VITALE IN RAVENNA: A SURVEY ON MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES" (PDF). Vol. 1: p. 2. Retrieved Accessed March 12, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Binda, L. (1998). "St. VITALE IN RAVENNA: A SURVEY ON MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES" (PDF). Vol. 1: p. 2. Retrieved Accessed March 12, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ferguson, S. ""Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna,"". Retrieved Accessed March 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Ferguson, S. ""Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna,"". Retrieved Accessed March 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Ferguson, S. ""Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna,"". Retrieved Accessed March 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Fergusson, James (1874). A history of architecture in all countries: from the earliest times to the present day, Volume 1. Cambridge: Dodd, Mead. pp. p. 398.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Binda, L. (1998). "St. VITALE IN RAVENNA: A SURVEY ON MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES" (PDF). Vol. 1: p. 2. Retrieved Accessed March 12, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Fergusson, James (1874). A history of architecture in all countries: from the earliest times to the present day, Volume 1. Cambridge: Dodd, Mead. pp. p. 399.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ martin, Cassidy. ""San Vitale."". Retrieved Accessed March 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Deichmann, Friedrich Wilhelm (1958). Frühchristliche Bauten und Mosaiken von Ravenna. Baden-Baden: Bruno Grimm. pp. 311–375.

- ^ Kleiner, Fred, Fred S. (2008). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: Volume I, Chapters 1-18 (12th ed.). Mason, OH: Wadsworth. p. 332. ISBN 0495467405.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kleiner and Mamiya. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, p. 333.

- ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Church,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Church,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Church,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Church,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Farber, Allen. ""Byzantine Justinian,"". Retrieved Accessed February 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kleiner and Mamiya. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, pp. 333, 336.

- ^ Vitale Italy, Basilica Di San. “San Vitale Church,”. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- ^ Sullivan, Mary Ann. ""San Vitale'"". Retrieved Accessed March 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

Further reading

- Andreescu-Treadgold, Irina and Warren Treadgold. "Procopius and the Imperial Panels of San Vitale." Art Bulletin, 79, 1997, pp. 708–723.

- Mango, Cyril. Art of the Byzantine Empire, 352-1453: Sources and Documents. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986.

- Mango, Cyril. Byzantine Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1976. ISBN 0 8109 1004 7.

- Procopius. On Buildings. Loeb Classical Library Series. Translated by H.B. Dewing and Glanville Downey. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961.

- Von Simson, Otto G. Sacred Fortress: Byzantine Art and Statecraft in Ravenna. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

External links

- Restoring the Mosaics of San Vitale by Livia Alberti (article)

- History of Byzantine Architecture: San Vitale (photos)

- Great Buildings On-line: San Vitale (photos)

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace Ravenna Pages (photos)