Cancer staging: Difference between revisions

rm pointless <small> tags |

Bluerasberry (talk | contribs) →Considerations in staging: bullets... |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Cancer staging''' is the process of determining the extent to which a [[cancer]] has developed by spreading. Contemporary practice is to assign a number from I-IV to a cancer, with I being an isolated cancer and IV being a cancer which as spread to the limit of what the assessment measures. The stage generally takes into account the size of a [[tumor]], how deeply it has penetrated within the wall of a hollow organ (intestine, urinary bladder), whether it has invaded adjacent [[organs]], how many regional [[lymph nodes]] it has [[metastasis|metastasized]] to (if any), and whether it has spread to distant organs. |

|||

A low cancer stage is the most important predictor of survival, and physicians recommend cancer treatment is primarily by staging. Thus, staging does not change with progression of the disease as it is used to assess [[prognosis]]. Patients' cancer, however, may be restaged after treatment but the staging established at diagnosis is rarely changed. |

|||

==TNM staging system== |

==TNM staging system== |

||

| Line 14: | Line 16: | ||

==Considerations in staging== |

==Considerations in staging== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Correct staging is critical because treatment (particularly the need for pre-operative therapy and/or for adjuvant treatment, the extent of surgery) is generally based on this parameter. Thus, incorrect staging would lead to improper treatment. |

Correct staging is critical because treatment (particularly the need for pre-operative therapy and/or for adjuvant treatment, the extent of surgery) is generally based on this parameter. Thus, incorrect staging would lead to improper treatment. |

||

For some common cancers the staging process is well-defined. For example, in the cases of breast cancer and prostate cancer, doctors routinely can identify that the cancer is early and that it has low risk of metastasis.<ref name="ASCOfive">{{Citation |author1 = American Society of Clinical Oncology |author1-link = American Society of Clinical Oncology |date = |title = Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question |publisher = [[American Society of Clinical Oncology]] |work = Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the [[ABIM Foundation]] |page = |url = http://choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/5things_12_factsheet_Amer_Soc_Clin_Onc.pdf |accessdate = August 14 2012}}, citing |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*{{cite PMID|19200416}} |

|||

*{{cite PMID|17509297}}</ref> In such cases, [[Specialty (medicine)|medical specialty]] [[professional organizations]] recommend against the use of [[Positron emission tomography|PET scans]], [[X-ray computed tomography|CT scans]], or [[Bone scintigraphy|bone scans]] because research shows that the risk of getting such procedures outweighs the possible benefits.<ref name="ASCOfive"/> Some of the problems associated with overtesting include patients receiving invasive procedures, [[overutilization|overutilizing]] medical services, getting unnecessary radiation exposure, and experiencing misdiagnosis.<ref name="ASCOfive"/> |

|||

===Pathologic staging=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Pathologic staging, where a pathologist examines sections of [[Tissue (biology)|tissue]], can be particularly problematic for two specific reasons: visual discretion and random sampling of tissue. "Visual discretion" means being able to identify single cancerous cells intermixed with healthy cells on a slide. Oversight of one [[Cell (biology)|cell]] can mean mistaging and lead to serious, unexpected spread of cancer. "Random sampling" refers to the fact that lymph nodes are cherry-picked from patients and random samples are examined. If cancerous cells present in the [[lymph node]] happen not to be present in the slices of tissue viewed, incorrect staging and improper treatment can result. |

||

===Current research=== |

|||

{{peacock|date=July 2012}} |

|||

New, highly sensitive methods of staging are in development. For example, the [[mRNA]] for GCC ([[guanylyl cyclase c]]), present only in the luminal aspect of [[intestinal epithelium]], can be identified using molecular screening ([[RT-PCR]]) with an astonishing degree of sensitivity and exactitude. Presence of GCC in any other tissue of the body represents [[colorectal metaplasia]]. Because of its exquisite sensitivity, RT-PCR screening for GCC nearly eliminates the possibility of underestimation of true disease stage. Researchers hope that staging with this level of precision will lead to more appropriate treatment and better [[prognosis]]. Furthermore, researchers hope that this same technique can be applied to other tissue-specific [[proteins]]. |

New, highly sensitive methods of staging are in development. For example, the [[mRNA]] for GCC ([[guanylyl cyclase c]]), present only in the luminal aspect of [[intestinal epithelium]], can be identified using molecular screening ([[RT-PCR]]) with an astonishing degree of sensitivity and exactitude. Presence of GCC in any other tissue of the body represents [[colorectal metaplasia]]. Because of its exquisite sensitivity, RT-PCR screening for GCC nearly eliminates the possibility of underestimation of true disease stage. Researchers hope that staging with this level of precision will lead to more appropriate treatment and better [[prognosis]]. Furthermore, researchers hope that this same technique can be applied to other tissue-specific [[proteins]]. |

||

Revision as of 19:57, 27 November 2012

Cancer staging is the process of determining the extent to which a cancer has developed by spreading. Contemporary practice is to assign a number from I-IV to a cancer, with I being an isolated cancer and IV being a cancer which as spread to the limit of what the assessment measures. The stage generally takes into account the size of a tumor, how deeply it has penetrated within the wall of a hollow organ (intestine, urinary bladder), whether it has invaded adjacent organs, how many regional lymph nodes it has metastasized to (if any), and whether it has spread to distant organs.

A low cancer stage is the most important predictor of survival, and physicians recommend cancer treatment is primarily by staging. Thus, staging does not change with progression of the disease as it is used to assess prognosis. Patients' cancer, however, may be restaged after treatment but the staging established at diagnosis is rarely changed.

TNM staging system

Cancer staging can be divided into a clinical stage and a pathologic stage. In the TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) system, clinical stage and pathologic stage are denoted by a small "c" or "p" before the stage (e.g., cT3N1M0 or pT2N0).

- Clinical stage is based on all of the available information obtained before a surgery to remove the tumor. Thus, it may include information about the tumor obtained by physical examination, radiologic examination, and endoscopy.

- Pathologic stage adds additional information gained by examination of the tumor microscopically by a pathologist.

Because they use different criteria, clinical stage and pathologic stage often differ. Pathologic staging is usually considered the "better" or "truer" stage because it allows direct examination of the tumor and its spread, contrasted with clinical staging which is limited by the fact that the information is obtained by making indirect observations at a tumor which is still in the body. However, clinical staging and pathologic staging should complement each other. Not every tumor is treated surgically, therefore pathologic staging is not always available. Also, sometimes surgery is preceded by other treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy which shrink the tumor, so the pathologic stage may underestimate the true stage.

This staging system is used for most forms of cancer, except brain tumors and hematological malignancies.

Considerations in staging

Correct staging is critical because treatment (particularly the need for pre-operative therapy and/or for adjuvant treatment, the extent of surgery) is generally based on this parameter. Thus, incorrect staging would lead to improper treatment.

For some common cancers the staging process is well-defined. For example, in the cases of breast cancer and prostate cancer, doctors routinely can identify that the cancer is early and that it has low risk of metastasis.[1] In such cases, medical specialty professional organizations recommend against the use of PET scans, CT scans, or bone scans because research shows that the risk of getting such procedures outweighs the possible benefits.[1] Some of the problems associated with overtesting include patients receiving invasive procedures, overutilizing medical services, getting unnecessary radiation exposure, and experiencing misdiagnosis.[1]

Pathologic staging

This article contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (July 2012) |

Pathologic staging, where a pathologist examines sections of tissue, can be particularly problematic for two specific reasons: visual discretion and random sampling of tissue. "Visual discretion" means being able to identify single cancerous cells intermixed with healthy cells on a slide. Oversight of one cell can mean mistaging and lead to serious, unexpected spread of cancer. "Random sampling" refers to the fact that lymph nodes are cherry-picked from patients and random samples are examined. If cancerous cells present in the lymph node happen not to be present in the slices of tissue viewed, incorrect staging and improper treatment can result.

Current research

This article contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (July 2012) |

New, highly sensitive methods of staging are in development. For example, the mRNA for GCC (guanylyl cyclase c), present only in the luminal aspect of intestinal epithelium, can be identified using molecular screening (RT-PCR) with an astonishing degree of sensitivity and exactitude. Presence of GCC in any other tissue of the body represents colorectal metaplasia. Because of its exquisite sensitivity, RT-PCR screening for GCC nearly eliminates the possibility of underestimation of true disease stage. Researchers hope that staging with this level of precision will lead to more appropriate treatment and better prognosis. Furthermore, researchers hope that this same technique can be applied to other tissue-specific proteins.

Systems of staging

Staging systems are specific for each type of cancer (e.g., breast cancer and lung cancer). Some cancers, however, do not have a staging system. Although competing staging systems still exist for some types of cancer, the universally-accepted staging system is that of the UICC, which has the same definitions of individual categories as the AJCC.

Systems of staging may differ between diseases or specific manifestations of a disease.

Blood

- Lymphoma: uses Ann Arbor staging

- Hodgkin's Disease: follows a scale from I–IV and can be indicated further by an A or B, depending on whether a patient is non-symptomatic or has symptoms such as fevers. It is known as the "Cotswold System" or "Modified Ann Arbor Staging System". [2]

Solid

For solid tumors, TNM is by far the most commonly used system, but it has been adapted for some conditions.

- Breast cancer: In breast cancer classification, staging is usually based on TNM,[3] but staging in I–IV may be used as well.

- Cervical and ovarian cancers: the "FIGO" system has been adopted into the TNM system. For premalignant dysplastic changes, the CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) grading system is used.[4]

- Colon cancer: originally consisted of four stages: A, B, C, and D (the Dukes staging system). More recently, colon cancer staging is indicated either by the original A-D stages or by TNM.[5]

- Kidney cancer: uses TNM.[6]

- Cancer of the larynx: Uses TNM.[7]

- Liver cancer: uses Stages I–IV.[8]

- Lung cancer: uses TNM.[9]

- Melanoma: TNM used. Also of importance are the "Clark level" and "Breslow depth" which refer to the microscopic depth of tumor invasion ("Microstaging").[10]

- Prostate cancer: outside of US, TNM almost universally used. Inside US, Jewett-Whitmore sometimes used.[11]

- Testicular cancer: uses TNM along with a measure of blood serum markers (TNMS).[12]

- Non-melanoma skin cancer: uses TNM.[13]

- Bladder cancer: uses TNM.[14]

Overall stage grouping

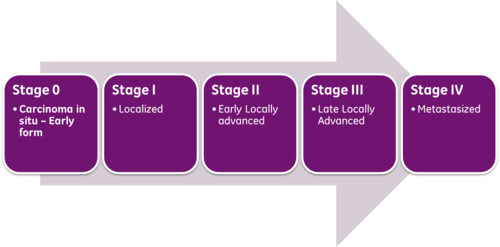

Overall Stage Grouping is also referred to as Roman Numeral Staging. This system uses numerals I, II, III, and IV (plus the 0) to describe the progression of cancer.

- Stage 0: carcinoma in situ.

- Stage I: cancers are localized to one part of the body.

- Stage II: cancers are locally advanced.

- Stage III: cancers are also locally advanced. Whether a cancer is designated as Stage II or Stage III can depend on the specific type of cancer; for example, in Hodgkin's Disease, Stage II indicates affected lymph nodes on only one side of the diaphragm, whereas Stage III indicates affected lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm. The specific criteria for Stages II and III therefore differ according to diagnosis.

- Stage IV: cancers have often metastasized, or spread to other organs or throughout the body.

Within the TNM system, a cancer may also be designated as recurrent, meaning that it has appeared again after being in remission or after all visible tumor has been eliminated. Recurrence can either be local, meaning that it appears in the same location as the original, or distant, meaning that it appears in a different part of the body.

Stage migration

Stage migration describes change in the distribution of stage in a particular cancer population induced by either a change in the staging system itself or else a change in technology which allows more sensitive detection of tumor spread and therefore more sensitivity in detecting spread of disease (e.g., the use of MRI scan). Stage migration can lead to curious statistical phenomena (for example, the Will Rogers phenomenon).

References

- ^ a b c American Society of Clinical Oncology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Clinical Oncology, retrieved August 14 2012

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help), citing - ^ "Hodgkin's Disease - Staging". oncologychannel. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Breast Cancer Treatment - National Cancer Institute". Cancer.gov. 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ Eric Lucas (2006-01-31). "FIGO staging of cervical carcinomas". Screening.iarc.fr. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Colon Cancer - Staging". oncologychannel. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Stages of kidney cancer". Cancerhelp.org.uk. 2010-06-30. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "The stages of cancer of the larynx". Cancerhelp.org.uk. 2010-07-28. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "The Liver Cancer Network Diagnosis: Staging Liver Cancer". Livercancer.com. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "eMedicine - Lung Cancer, Staging: Article by Isaac Hassan". Emedicine.medscape.com. 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "malignant melanoma: staging". Chorus.rad.mcw.edu. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Prostate Cancer Staging Systems". oncologychannel. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ American Cancer Society: How Is Testicular Cancer Staged?[dead link]

- ^ Skin Cancer Staging[dead link]

- ^ "ACS : How Is Bladder Cancer Staged?". Cancer.org. 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-10-14.