Banach space: Difference between revisions

m →Classical spaces: giving better links |

→Reflexivity: examples of reflexive spaces |

||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

<blockquote>'''Theorem.''' If ''X'' is a Banach space, then ''X'' is reflexive if and only if {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} is reflexive.</blockquote> |

<blockquote>'''Theorem.''' If ''X'' is a Banach space, then ''X'' is reflexive if and only if {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} is reflexive.</blockquote> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

<blockquote>'''Theorem.''' Suppose that ''X''<sub>1</sub>, ..., ''X<sub>n</sub>'' are normed spaces and that ''X'' = ''X''<sub>1</sub> ⊕ ... ⊕ ''X<sub>n</sub>''. Then ''X'' is reflexive if and only if each ''X<sub>j</sub>'' is reflexive.</blockquote> |

<blockquote>'''Theorem.''' Suppose that ''X''<sub>1</sub>, ..., ''X<sub>n</sub>'' are normed spaces and that ''X'' = ''X''<sub>1</sub> ⊕ ... ⊕ ''X<sub>n</sub>''. Then ''X'' is reflexive if and only if each ''X<sub>j</sub>'' is reflexive.</blockquote> |

||

Hilbert spaces are reflexive. The ''L''<sup>''p''</sup> spaces are reflexive when {{nowrap|1 < ''p'' < ∞}}. More generally, [[uniformly convex space]]s are reflexive, by the [[Milman–Pettis theorem]]. The spaces ''c''<sub>0</sub>, ℓ<sup>1</sup>, ''L''<sup>1</sup>([0, 1]), ''C''([0, 1]) are not reflexive. In these examples of non reflexive spaces ''X'', the bidual {{nowrap|''X'' ′′}} is "much larger" than ''X'', namely, the quotient {{nowrap|''X'' ′′ / ''X''}} is infinite dimensional, and even non separable. However, Robert C. James has constructed an example of a non-reflexive space, usually denoted by ''J'', such that the quotient {{nowrap|''J'' ′′ / ''J''}} is one dimensional. Furthermore, this space ''J'' is isometrically isomorphic to its bidual.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| author = R. C. James |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| title = A non-reflexive Banach space isometric with its second conjugate space |

|||

| journal = Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |

|||

| volume = 37 |

|||

| pages = 174–177 |

|||

| year = 1951 }} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>'''Theorem.''' A Banach space ''X'' is reflexive if and only if its unit ball is [[compact space|compact]] in the [[weak topology]].</blockquote> |

<blockquote>'''Theorem.''' A Banach space ''X'' is reflexive if and only if its unit ball is [[compact space|compact]] in the [[weak topology]].</blockquote> |

||

When ''X'' is reflexive, it follows that all closed and bounded [[Convex set|convex subsets]] of ''X'' are weakly compact |

When ''X'' is reflexive, it follows that all closed and bounded [[Convex set|convex subsets]] of ''X'' are weakly compact. In a Hilbert space ''H'', the weak compactness of the unit ball is very often used in the following way: every bounded sequence in ''H'' has weakly convergent subsequences. |

||

Weak compactness of the unit ball provides a tool for finding solutions in reflexive spaces to certain [[Infinite-dimensional optimization|optimization problems]]. For example, every [[Convex function|convex]] continuous function on the unit ball ''B'' of a reflexive space attains its minimum at some point in ''B''. |

Weak compactness of the unit ball provides a tool for finding solutions in reflexive spaces to certain [[Infinite-dimensional optimization|optimization problems]]. For example, every [[Convex function|convex]] continuous function on the unit ball ''B'' of a reflexive space attains its minimum at some point in ''B''. |

||

| Line 165: | Line 175: | ||

As a special case of the preceding result, when ''X'' is a reflexive space over '''R''', every continuous linear functional ''f'' in {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} attains its maximum {{nowrap|ǁ''f ''ǁ}} on the unit ball of ''X''. The following [[James' theorem|theorem of Robert C. James]] provides a converse statement. |

As a special case of the preceding result, when ''X'' is a reflexive space over '''R''', every continuous linear functional ''f'' in {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} attains its maximum {{nowrap|ǁ''f ''ǁ}} on the unit ball of ''X''. The following [[James' theorem|theorem of Robert C. James]] provides a converse statement. |

||

<blockquote>'''James' Theorem''' For a Banach space the following two properties are equivalent: |

<blockquote>'''James' Theorem.''' For a Banach space the following two properties are equivalent: |

||

* ''X'' is reflexive. |

* ''X'' is reflexive. |

||

* for all ''f'' in {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} there exists ''x'' in ''X'' with ǁ''x''ǁ ≤ 1, so that {{nowrap|''f'' (''x'') {{=}}}} {{nowrap|ǁ''f ''ǁ.}}</blockquote> |

* for all ''f'' in {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} there exists ''x'' in ''X'' with ǁ''x''ǁ ≤ 1, so that {{nowrap|''f'' (''x'') {{=}}}} {{nowrap|ǁ''f ''ǁ.}}</blockquote> |

||

The theorem can be extended to a characterization of weakly compact convex sets. |

|||

| ⚫ | On every non |

||

<br /> |

|||

| ⚫ | On every non-reflexive Banach space ''X'', there exist continuous linear functionals that are not ''norm-attaining''. However, the [[Errett Bishop|Bishop]]–[[Robert Phelps|Phelps]] theorem<ref>see E. Bishop and R. Phelps, "A proof that every Banach space is subreflexive". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. '''67''' (1961), 97–98.</ref> states that norm-attaining functionals are norm dense in the dual {{nowrap|''X'' ′}} of ''X''. |

||

== Schauder bases == |

== Schauder bases == |

||

Revision as of 18:28, 8 May 2013

In mathematics, more specifically in functional analysis, a Banach space (pronounced [ˈbanax]) is a complete normed vector space. Informally, a Banach space is a vector space with a metric that allows the computation of vector length and distance between vectors and is complete in the sense that a Cauchy sequence of vectors always converges to a well defined limit in the space.

Banach spaces are named after the Polish mathematician Stefan Banach, who introduced and made a systematic study of them in 1920–1922 along with Hans Hahn and Eduard Helly.[1] Banach spaces originally grew out of the study of function spaces by Hilbert, Fréchet, and Riesz earlier in the century. Banach spaces play a central role in functional analysis. In other areas of analysis, the spaces under study are often Banach spaces.

General theory

Definition

A Banach space is a vector space X over the field of real numbers R or complex numbers C which is equipped with a norm and which is complete with respect to that norm, that is to say, for every Cauchy sequence in X, there exists an element x in X such that

- .

The vector space structure allows to relate the behavior of Cauchy sequences to that of converging series of vectors. A normed space X is a Banach space if and only if each absolutely convergent series in X converges,

In metric spaces, completeness is a property of the metric, which can be lost if a different metric inducing the same topology is considered. However, the completeness of a normed space is preserved if the given norm is replaced by an equivalent one.

All norms on a finite dimensional vector space are equivalent. Every finite-dimensional normed space is a Banach space.[2]

Linear operators, isomorphisms

If X and Y are normed spaces over the same ground field K, the set of all continuous K-linear maps T : X → Y is denoted by B(X, Y). In infinite-dimensional spaces, not all linear maps are continuous. A linear mapping from a normed space X to another normed space is continuous if and only if it is bounded on the closed unit ball of X. Thus, the vector space B(X, Y) can be given the operator norm

When Y a Banach space, the space B(X, Y) is a Banach space with respect to this norm.

If X is a Banach space, the space B(X) = B(X, X) forms a unital Banach algebra; the multiplication operation is given by the composition of linear maps.

If X and Y are normed spaces, they are isomorphic normed spaces if there exists a linear bijection T from X onto Y such that T and its inverse T −1 are continuous. If one of the two spaces X or Y is complete (or reflexive, separable, etc.) then so is the other space. Two normed spaces X and Y are isometrically isomorphic if in addition, T is an isometry, i.e., ||T(x)|| = ||x|| for every x in X. The Banach-Mazur distance d(X, Y) between two isomorphic but not isometric spaces X and Y gives a measure of how much the two spaces X and Y differ.

Basic notions

Every normed space X can be isometrically embedded in a Banach space. More precisely, there is a Banach space Y and an isometric mapping T : X → Y such that T(X) is dense in Y. If Z is another Banach space such that there is an isometric isomorphism from X onto a dense subset of Z, then Z is isometrically isomorphic to Y.

This Banach space Y is the completion of the normed space X. The underlying metric space for Y is the same as the metric completion of X, with the vector space operations extended from X to Y. The completion of X is often denoted by .

The cartesian product X×Y of two normed spaces is not canonically equipped with a norm. However, several equivalent norms are commonly used,[3] such as

and give rise to isomorphic normed spaces. In this sense, the product X×Y (or the direct sum X ⊕ Y) is complete if and only if the two factors are complete.

If M is a closed subspace of a normed space X, there is a natural norm on the quotient space X / M,

The quotient X / M is a Banach space when X is complete. The quotient map from X onto X / M, sending x in X to its class x+M, is linear, onto and has norm 1, except when M = X, in which case the quotient is the null space.

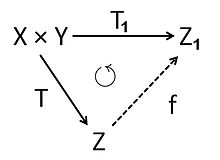

Suppose that X and Y are Banach spaces and that T ∈ B(X, Y). There exists a canonical factorization of T as

where the first map π is the quotient map, and the second map T1 sends every class x + Ker(T) in the quotient to the image T(x) in Y. This is well defined because all elements in the same class have the same image. The mapping T1 is a linear bijection from X / Ker T onto the range T(X), whose inverse need not be bounded.

Classical spaces

Basic examples[4] of Banach spaces include the Lp spaces and their special cases, the sequence spaces ℓp; the space C(K) of continuous scalar functions on a compact Hausdorff space K, equipped with the max norm,

According to the Banach–Mazur theorem, every Banach space is isometrically isomorphic to a subspace of some C(K).[5] For every separable Banach space X, there is a closed subspace M of ℓ1 such that X ≅ ℓ1/M.

A most important example of Banach space is that of a Hilbert space. A Hilbert space H on K = R or C is complete for a norm of the form

is the inner product, a K-valued function on H × H, linear in x and such that

The space L2 is a fundamental example of Hilbert space.

The Hardy spaces, the Sobolev spaces are examples of Banach spaces that are related to Lp spaces and have additional structure. They are important in different branches of analysis, Harmonic analysis and Partial differential equations among others.

A Banach algebra is a Banach space A over K = R or C, together with a structure of algebra over K, such that the product map (a, b) ∈ A × A → a b ∈ A is continuous. An equivalent norm on A can be found so that ǁa bǁ ≤ ǁaǁ ǁbǁ for all a, b in A. The Banach space C(K), with the pointwise product, is a Banach algebra. The disk algebra A(D) consists of functions holomorphic in the open unit disk D in the complex plane and continuous on the closure of D. Equipped with the max norm on the closure of D, the disk algebra A(D) is a closed subalgebra of . The Wiener algebra A(T) is the algebra of functions on the unit circle T with absolutely convergent Fourier series. Via the map associating a function on T to the sequence of its Fourier coefficients, this algebra is isomorphic to the Banach algebra ℓ1(Z), where the product is the convolution of sequences. For every Banach space X, the space B(X) of bounded linear operators on X, with the composition of maps as product, is a Banach algebra.

A C*-algebra is a complex Banach algebra A with an antilinear involution a → a* such that ǁa*aǁ = ǁaǁ2. The space B(H) of bounded linear operators on a Hilbert space H is a fundamental example of C*-algebra. The Gelfand–Naimark theorem states that every C*-algebra is isometrically isomorphic to a C*-subalgebra of some B(H). The space C(K) of complex continuous functions on a compact Hausdorff space K is an example of commutative C*-algebra, where the involution associates to every function f its complex conjugate .

Dual space

If X is a normed space and K is the underlying field (either the real or the complex numbers), one can define the continuous dual space as X ′ = B(X, K), the space of continuous linear maps from X into K. Since K is a Banach space (using the absolute value as norm), the dual X ′ is a Banach space, for every normed space X.

Theorem. Let X be a normed space. If X ′ is separable, then X is separable.

The main tool for proving the existence of continuous linear functionals is the Hahn–Banach theorem.

Hahn–Banach Theorem. Let X be a vector space over the field K = R or K = C. Let further

- Y ⊆ X be a linear subspace,

- p : X → R be a sublinear function and

- f : Y → K be a linear functional so that Re f(y) ≤ p(y) for all y in Y.

Then, there exists a linear functional F : X → K so that

In particular, every continuous linear functional on a subspace of a normed space can be continuously continued on the whole space, without increasing the norm of the functional.

If M is a closed linear subspace in X, one can associate the orthogonal of M in the dual,

The orthogonal M⊥ is a closed linear subspace of the dual. The dual of M is isometrically isomorphic to X ′ / M⊥. The dual of X / M is isometrically isomorphic to M⊥.

Weak topologies

The continuous dual space can be used to define a new topology on X: the weak topology. It is the coarsest topology on X for which all elements x ′ in X ′ are continuous. By this definition, the norm topology is finer than the weak topology. Note that the requirement that the maps x ′ be continuous is essential; if X is infinite-dimensional, there exist linear maps which are not continuous, and therefore not bounded. The space X* of all linear maps into K (which is called the algebraic dual space to distinguish it from X ′) also induces a weak topology which is finer than that induced by the continuous dual since X ′ ⊆ X*.

On a dual space X ′, there is a topology weaker than the weak topology of X ′, called weak* topology. It is the coarsest topology on X ′ for which all evaluation maps x′∈X ′ → x′(x), x∈X, are continuous. Its importance comes from the Banach–Alaoglu theorem.

Banach–Alaoglu Theorem. Let X be a normed vector space. Then the closed unit ball of the dual space B ′ := {x ∈ X ′ | ǁxǁ ≤ 1} is compact in the weak* topology.

The Banach–Alaoglu theorem depends on Tychonoff's theorem about infinite products of compact spaces. When X is separable, the unit ball B ′ of the dual is a metrizable compact in the weak* topology.

Examples of dual spaces

The dual of c0 is isometrically isomorphic to ℓ1. The dual of Lp([0, 1]) is isometrically isomorphic to Lq([0, 1]) when 1 ≤ p < ∞ and 1/p + 1/q = 1.

For every vector y in a Hilbert space H, the mapping

defines a continuous linear functional f y on H. The Riesz representation theorem states that every continuous linear functional on H is of the form f y for a uniquely defined vector y in H. The mapping y ∈ H → f y is an antilinear isometric bijection from H onto its dual H ′. When the scalars are real, this map is an isometric isomorphism.

When K is a compact Hausdorff topological space, the dual M(K) of C(K) is the space of Radon measures in the sense of Bourbaki.[6] The subset P(K) of M(K) consisting of non-negative measures of mass 1 (probability measures) is a convex w*-closed subset of the unit ball of M(K). The extreme points of P(K) are the Dirac measures on K. The set of Dirac measures on K, equipped with the w*-topology, is homeomorphic to K.

Banach-Stone Theorem. If K and L are compact Hausdorff spaces and if C(K) and C(L) are isometrically isomorphic, then the topological spaces K and L are homeomorphic.[7][8]

The result has been extended by Amir[9] and Cambern[10] to the case when the multiplicative Banach–Mazur distance between C(K) and C(L) is < 2. The theorem is no longer true when the distance is equal to 2.[11]

In the commutative Banach algebra C(K), the maximal ideals are precisely kernels of Dirac mesures on K,

More generally, by the Gelfand-Mazur theorem, the maximal ideals of a unital commutative Banach algebra can be identified with its characters---not merely as sets but as topological spaces: the former with the hull-kernel topology and the latter with the w*-topology. In this identification, the maximal ideal space can be viewed as a w*-compact subset of the unit ball in the dual A ′.

Theorem. If K is a compact Hausdorff space, then the maximal ideal space Ξ of the Banach algebra C(K) is homeomorphic to K.[7]

Not every unital commutative Banach algebra is of the form C(K) for some compact Hausdorff space K. However, this statement holds if one places C(K) in the smaller category of commutative C*-algebras. Gelfand's representation theorem for commutative C*-algebras states that every commutative unital C*-algebra A is isometrically isomorphic to a C(K) space.[12] The Hausdorff compact space K here is again the maximal ideal space, also called the spectrum of A in the C*-algebra context.

Banach's theorems

Here are the main general results about Banach spaces that go back to the time of Banach's book (Banach (1932) and are related to the Baire category theorem. According to this theorem, a complete metric space (such as a Banach space, a Fréchet space or an F-space) cannot be equal to a union of countably many closed subsets with empty interiors. Therefore, a Banach space cannot be the union of countably many closed subspaces, unless it is already equal to one of them; a Banach space with a countable Hamel basis is finite-dimensional.

Banach–Steinhaus Theorem. Let X be a Banach space and Y be a normed vector space. Suppose that F is a collection of continuous linear operators from X to Y. The uniform boundedness principle states that if for all x in X we have , then

The Banach–Steinhaus theorem is not limited to Banach spaces. It can be extended for example to the case where X is a Fréchet space, provided the conclusion is modified as follows: under the same hypothesis, there exists a neighborhood U of 0 in X such that all T in F are uniformly bounded on U,

The Open Mapping Theorem. Let X and Y be Banach spaces and T : X → Y be a continuous linear operator. Then T is surjective if and only if T is an open map.

Corollary. Every one-to-one bounded linear operator from a Banach space onto a Banach space is an isomorphism.

The First Isomorphism Theorem for Banach spaces. Suppose that X and Y are Banach spaces and that T ∈ B(X, Y). Suppose further that the range of T is closed in Y. Then X / Ker(T) is isomorphic to T(X).

This result is a direct consequence of the preceding Banach isomorphism theorem and of the canonical factorization of bounded linear maps.

Corollary. If a Banach space X is the internal direct sum of closed subspaces M1, ..., Mn, then X is isomorphic to M1 ⊕ ... ⊕ Mn.

This is another consequence of Banach's isomorphism theorem, applied to the continuous bijection from M1 ⊕ ... ⊕ Mn onto X sending (m1, ... , mn) to the sum m1 + ... + mn.

The Closed Graph Theorem. Let T : X → Y be a linear mapping between Banach spaces. The graph of T is closed in X × Y if and only if T is continuous.

Reflexivity

For every normed space X, there is a natural map F : X → X ′′ (the dual of the dual = bidual) defined by

- F(x)(f) = f(x) for all x in X and f in X ′.

Because F(x) is a continuous linear functional on X ′, it is an element of X ′′. The map F : x → F(x) is thus a map X → X ′′. As a consequence of the Hahn–Banach theorem, this map is injective and isometric.

If F is also surjective, then the normed space X is called reflexive. Since the dual of a normed space is complete, every reflexive normed space is a Banach space. Reflexive spaces have many important geometric properties.

Theorem. If X is a reflexive Banach space, every closed subspace of X and every quotient space of X are reflexive.

This is a consequence of the Hahn–Banach theorem. Further, by the open mapping theorem, if there is a bounded linear operator from the Banach space X onto the Banach space Y, then Y is reflexive.

Theorem. If X is a Banach space, then X is reflexive if and only if X ′ is reflexive.

Corollary. Let X be a reflexive Banach space. Then X is separable if and only if X ′ is separable.

Indeed, if the dual Y ′ of a Banach space Y is separable, then Y is separable. If X is reflexive and separable, then the dual of X ′ is separable, so X ′ is separable.

Theorem. Suppose that X1, ..., Xn are normed spaces and that X = X1 ⊕ ... ⊕ Xn. Then X is reflexive if and only if each Xj is reflexive.

Hilbert spaces are reflexive. The Lp spaces are reflexive when 1 < p < ∞. More generally, uniformly convex spaces are reflexive, by the Milman–Pettis theorem. The spaces c0, ℓ1, L1([0, 1]), C([0, 1]) are not reflexive. In these examples of non reflexive spaces X, the bidual X ′′ is "much larger" than X, namely, the quotient X ′′ / X is infinite dimensional, and even non separable. However, Robert C. James has constructed an example of a non-reflexive space, usually denoted by J, such that the quotient J ′′ / J is one dimensional. Furthermore, this space J is isometrically isomorphic to its bidual.[13]

Theorem. A Banach space X is reflexive if and only if its unit ball is compact in the weak topology.

When X is reflexive, it follows that all closed and bounded convex subsets of X are weakly compact. In a Hilbert space H, the weak compactness of the unit ball is very often used in the following way: every bounded sequence in H has weakly convergent subsequences.

Weak compactness of the unit ball provides a tool for finding solutions in reflexive spaces to certain optimization problems. For example, every convex continuous function on the unit ball B of a reflexive space attains its minimum at some point in B.

As a special case of the preceding result, when X is a reflexive space over R, every continuous linear functional f in X ′ attains its maximum ǁf ǁ on the unit ball of X. The following theorem of Robert C. James provides a converse statement.

James' Theorem. For a Banach space the following two properties are equivalent:

- X is reflexive.

- for all f in X ′ there exists x in X with ǁxǁ ≤ 1, so that f (x) = ǁf ǁ.

The theorem can be extended to a characterization of weakly compact convex sets.

On every non-reflexive Banach space X, there exist continuous linear functionals that are not norm-attaining. However, the Bishop–Phelps theorem[14] states that norm-attaining functionals are norm dense in the dual X ′ of X.

Schauder bases

A Schauder basis in a Banach space X is a sequence {en}n≥0 of vectors in X with the property that for every vector x in X, there exist uniquely defined scalars {an}n≥0 depending on x, such that

It follows from the Banach–Steinhaus theorem that the linear mappings {Pn} are uniformly bounded by some constant C. Let {e*n} denote the coordinate functionals which assign to every x in X the coordinate an of x in the above expansion. They are called biorthogonal functionals. When the basis vectors have norm 1, the coordinate functionals e*n have norm ≤ 2C in the dual of X.

Most classical spaces have explicit bases. The Haar system {hn} is a basis for Lp([0, 1]), 1 ≤ p < ∞. The trigonometric system is a basis in Lp(T) when 1 < p < ∞. Let the Schauder system be the family of continuous functions on [0, 1] consisting of the function 1 and of all functions fn such that fn(0) = 0 and that the derivative of fn is equal to hn. In the space C([0, 1]), the Schauder system is a basis.[15]

Since every x in X is the limit of Pn(x), with Pn of finite rank and uniformly bounded, the space X satisfies the bounded approximation property. The first example[16] by Enflo of a space failing the approximation property was at the same time the first example of a Banach space without basis.

A basis is boundedly complete if for every sequence {an}n≥0 of scalars such that the partial sums

are bounded in X, the sequence {Vn} converges in X. The unit vector basis for ℓp, 1 ≤ p < ∞, is boundedly complete, while it is not boundedly complete in c0.

A basis is shrinking if for every bounded linear functional f on X, the sequence of non-negative numbers

tends to 0, where Fn is the linear span of the basis vectors em for m ≥ n. The unit vector basis for ℓp, 1 < p < ∞, or for c0, is shrinking. It is not shrinking in ℓ1.

Robert C. James characterized reflexivity in Banach spaces with basis: the space X with a Schauder basis is reflexive if and only if the basis is both shrinking and boundedly complete.[17] In this case, the biorthogonal functionals form a basis of the dual of X.

Tensor product

Let X and Y be two K-vector spaces. The tensor product X ⊗ Y of X and Y is a K-vector space Z with a bilinear mapping T : X × Y → Z which has the following universal property: If T1 : X × Y → Z1 is any bilinear mapping into a K-vector space Z1, then there exists a unique linear mapping f : Z → Z1 such that T1 = f o T.

The image under T of a couple (x, y) in X × Y is denoted by x ⊗ y, and called a simple tensor. Every element z in X ⊗ Y is a finite sum of such simple tensors.

There are various norms that can be placed on the tensor product of the underlying vector spaces, amongst others the projective cross norm and injective cross norm introduced by A. Grothendieck in 1955.[18]

In general, the tensor product of complete spaces is not complete again. When working with Banach spaces, it is customary to call projective tensor product of two Banach spaces X and Y the completion of the algebraic tensor product X ⊗ Y equipped with the projective tensor norm, and similarly for the injective tensor product . Grothendieck proved in particular that

where K is a compact Hausdorff space, C(K, Y) the Banach space of continuous functions from K to Y and L1([0, 1], Y) the space of Bochner-measurable and integrable functions from [0, 1] to Y, and where the isomorphisms are isometric. The two isomorphisms above are the respective extensions of the map sending the tensor f ⊗ y to the vector-valued function s ∈ K → f(s)y ∈ Y.

There is a natural norm 1 linear map

obtained by extending the identity map of the algebraic tensor product. Grothendieck related the approximation problem to the question of whether the above map is always one-to-one.

Grothendieck conjectured that and must be different whenever X and Y are infinite dimensional Banach spaces. This was disproved by Gilles Pisier in 1983.[19]

Placement in the hierarchy of mathematical structures

Every Hilbert space X is a Banach space because, by definition, a Hilbert space is complete with respect to the norm associated with its inner product, where a norm and an inner product are said to be associated if for all x ∈ X.

The converse is not always true; not every Banach space is a Hilbert space. A necessary and sufficient condition for a Banach space X to be associated to an inner product (which will then necessarily make X into a Hilbert space) is the parallelogram identity:

for all x and y in X, and where is the norm on X. So, for example, while Rn is a Banach space with respect to any norm defined on it, it is only a Hilbert space with respect to the Euclidean norm. Similarly, as an infinite-dimensional example, the Lebesgue space Lp is always a Banach space but is only a Hilbert space when p = 2.

If the norm of a Banach space satisfies this identity, the associated inner product which makes it into a Hilbert space is given by the polarization identity. If X is a real Banach space, then the polarization identity is

whereas if X is a complex Banach space, then the polarization identity is given by (assuming that scalar product is linear in first argument):

The necessity of this condition follows easily from the properties of an inner product. To see that it is sufficient—that the parallelogram law implies that the form defined by the polarization identity is indeed a complete inner product—one verifies algebraically that this form is additive, whence it follows by induction that the form is linear over the integers and rationals. Then, since every real is the limit of some Cauchy sequence of rationals, the completeness of the norm extends the linearity to the whole real line. In the complex case, one can also check that the bilinear form is linear over i in one argument, and conjugate linear in the other.

Examples

Here K denotes the field of real numbers or complex numbers, I is a closed and bounded interval [a, b] and p, q are real numbers with 1 < p, q < ∞ so that

The symbol Σ denotes a σ-algebra of sets, and Ξ denotes just an algebra of sets (for spaces only requiring finite additivity, such as the ba space). The symbol μ denotes a positive measure: that is, a real-valued positive set function defined on a σ-algebra which is countably additive.

| Classical Banach spaces | |||||

| Dual space | Reflexive | weakly complete | Norm | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kn | Kn | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓnp | ℓnq | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓn∞ | ℓn1 | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓp | ℓq | Yes | Yes | ||

| ℓ1 | ℓ∞ | No | Yes | ||

| ℓ∞ | ba | No | No | ||

| c | ℓ1 | No | No | ||

| c0 | ℓ1 | No | No | Isomorphic but not isometric to c. | |

| bv | ℓ1 + K | No | Yes | ||

| bv0 | ℓ1 | No | Yes | ||

| bs | ba | No | No | Isometrically isomorphic to ℓ∞. | |

| cs | ℓ1 | No | No | Isometrically isomorphic to c. | |

| B(X, Ξ) | ba(Ξ) | No | No | ||

| C(X) | rca(X) | No | No | X is a compact Hausdorff space. | |

| ba(Ξ) | ? | No | Yes | is the variation of μ | |

| ca(Σ) | ? | No | Yes | A closed subspace of ba(Σ). | |

| rca(Σ) | ? | No | Yes | A closed subspace of ca(Σ). | |

| Lp(μ) | Lq(μ) | Yes | Yes | ||

| BV(I) | ? | No | Yes | Vf(I) is the total variation of f | |

| NBV(I) | ? | No | Yes | NBV(I) consists of BV(I) functions such that | |

| AC(I) | K + L∞(I) | No | Yes | Isomorphic to the Sobolev space W1,1(I). | |

| Cn[a,b] | rca([a,b]) | No | No | Isomorphic to Rn ⊕ C([a,b]), essentially by Taylor's theorem. | |

Derivatives

Several concepts of a derivative may be defined on a Banach space. See the articles on the Fréchet derivative and the Gâteaux derivative for details. The Fréchet derivative allows for an extension of the concept of a directional derivative to Banach spaces. The Gâteaux derivative allows for an extension of a directional derivative to locally convex topological vector spaces. Fréchet differentiability is a stronger condition than Gâteaux differentiability. The quasi-derivative is another generalization of directional derivative that implies a stronger condition than Gâteaux differentiability, but a weaker condition than Fréchet differentiability.

Further results

Theorem. If there are Banach spaces which are invariant under the action of an integrable group representation and give their atomic decompositions with respect to coherent states, then the atoms arise from a single element under the group action.[20]

Theorem. If X is a separable infinite dimensional Banach space then its isomorphism class has infinite diameter with respect to the Banach-Mazur distance.[21]

Theorem. If X is a separable Banach space such that for some K < ∞ every isomorph of X is K-elastic the X is finite dimensional.[21]

Theorem. Every n-homogeneous continuous polynomial on a Banach space E which is weakly continuous on the unit ball of E is weakly uniformly continuous on the unit ball of E.[22]

Theorem. If X is a strictly convex Banach space with the Radon-Nikodym property, then the quasihyperbolic geodesics in X are unique.[23]

Generalizations

Several important spaces in functional analysis, for instance the space of all infinitely often differentiable functions R → R, or the space of all distributions on R, are complete but are not normed vector spaces and hence not Banach spaces. In Fréchet spaces one still has a complete metric, while LF-spaces are complete uniform vector spaces arising as limits of Fréchet spaces.

See also

Notes

- ^ Bourbaki 1987, V.86

- ^ Megginson, Robert E. "An Introduction to Banach Space Theory". Graduate Texts in Mathematics 183. Springer-Verlag. Retrieved 1998.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ see Banach (1932), p. 182.

- ^ see Banach (1932), pp. 11-12.

- ^ see Banach (1932), Th. 9 p. 185.

- ^ see N. Bourbaki, (2004), "Integration I", Springer Verlag, ISBN 3-540-41129-1.

- ^ a b Eilenberg, Samuel (Jan 22, 1942). "Banach Space Methods in Topology". Annals of Mathematics. 43 (3): 568.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ see also Banach (1932), p. 170 for metrizable K and L.

- ^ see D. Amir, "On isomorphisms of continuous function spaces". Israel J. Math. 3 (1965), 205–210.

- ^ M. Cambern, "A generalized Banach-Stone theorem". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 17 (1966), 396–400, and "On isomorphisms with small bound". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 18 (1967), 1062–1066.

- ^ H. B. Cohen, "A bound-two isomorphism between C(X) Banach spaces". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 50 (1975), 215–217.

- ^ see for example W. Arveson, (1976), "An Invitation to C*-Algebra", Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90176-0.

- ^ R. C. James (1951). "A non-reflexive Banach space isometric with its second conjugate space". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 37: 174–177.

- ^ see E. Bishop and R. Phelps, "A proof that every Banach space is subreflexive". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 67 (1961), 97–98.

- ^ see Lindenstrauss & Tzafriri (1977) p. 3.

- ^ see P. Enflo, "A counterexample to the approximation property in Banach spaces". Acta Math. 130, 309–317(1973).

- ^ see R.C. James, "Bases and reflexivity of Banach spaces". Ann. of Math. (2) 52, (1950). 518–527. See also Lindenstrauss & Tzafriri (1977) p. 9.

- ^ see A. Grothendieck, "Produits tensoriels topologiques et espaces nucléaires". Mem. Amer. Math. Soc. 1955 (1955), no. 16, 140 pp., and A. Grothendieck, "Résumé de la théorie métrique des produits tensoriels topologiques". Bol. Soc. Mat. São Paulo 8 1953 1–79.

- ^ see G. Pisier, "Counterexamples to a conjecture of Grothendieck". Acta Math. 151 (1983), no. 3-4, 181–208.

- ^ Hans G. Feichtinger, K.H Gröchenig (1989). "Banach spaces related to integrable group representations and their atomic decompositions, I". Journal of Functional Analysis. 86 (2): 307–340.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b W. B. Johnson and E. Odell (2005). "The diameter of the isomorphism class of a Banach space". Annals of Mathematics. Second Series. 162 (1): 423–437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Aron, R.M (Jan 15, 1983). "Weakly continuous mappings on Banach spaces". Journal of Functional Analysis. 52 (2): 189–204.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Rasila, Antti (Jan 5, 2013). "On Quasihyperbolic Geodesics in Banach Spaces". ArXiv.org.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link)

References

- Banach, Stefan (1932), Théorie des opérations linéaires, Monografie Matematyczne, vol. 1, Warszawa: Subwencji Funduszu Kultury Narodowej, Zbl 0005.20901.

- Beauzamy, Bernard (1985 [1982]), Introduction to Banach Spaces and their Geometry (Second revised ed.), North-Holland

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link). - Bourbaki, Nicolas (1987), Topological vector spaces, Elements of mathematics, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-13627-9.

- Dunford, Nelson; Schwartz, Jacob T. (1958), Linear Operators. I. General Theory, With the assistance of W. G. Bade and R. G. Bartle. Pure and Applied Mathematics, Vol. 7, Interscience Publishers, Inc., New York, MR 0117523

- Lindenstrauss, Joram; Tzafriri, Lior (1977), Classical Banach Spaces I, Sequence Spaces, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, vol. 92, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-08072-4.

- Prof. Dr. A. Deitmar: Funktionalanalysis Skript WS2011/12 < http://www.mathematik.uni-tuebingen.de/~deitmar/LEHRE/frueher/2011-12/FA/FA.pdf>

- Megginson, Robert E. (1991), An Introduction to Banach Space Theory, Springer-Verlag.

- Ryan, Raymond A. (2000), Introduction to Tensor Products of Banach Spaces, Springer-Verlag.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}C(K){\widehat {\otimes }}_{\varepsilon }Y&\simeq C(K,Y),\\L^{1}([0,1]){\widehat {\otimes }}_{\pi }Y&\simeq L^{1}([0,1],Y),\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fdda0e4532c785e0ccddd2743db91e009ace27bb)

![{\displaystyle \|f\|=\sum _{i=0}^{n}\sup \nolimits _{x\in [a,b]}\left|f^{(i)}(x)\right|}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e1a1a53ee5f74ba1c00ded97c44862d0bf691501)