Commentary on the Apocalypse: Difference between revisions

→Principal copies: usual names |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

*The [[Nájera]] fragment. 9th century. Abbey of [[Santo Domingo de Silos]]. |

*The [[Nájera]] fragment. 9th century. Abbey of [[Santo Domingo de Silos]]. |

||

*''Beatus'' of the [[Monasteries of San Millán de la Cogolla|Monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla]]. Ca. 930. [[Madrid]]. Real Academia de la Historia. Ms. 33. |

*''Beatus'' of the [[Monasteries of San Millán de la Cogolla|Monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla]]. Ca. 930. [[Madrid]]. Real Academia de la Historia. Ms. 33. |

||

*[[Escorial Beatus |

*[[Escorial Beatus]] of San Millán. Ca. 950 / 955. Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo. Ms. & II. 5. 225 x 355 mm. 151 leaves; 52 miniatures. |

||

*[[Morgan Beatus |

*[[Morgan Beatus]] or ''Beatus'' of San Miguel de Escalada. Ca. 960. Pierpont Morgan Library ([[New York]]). Ms 644. 280 x 380 mm. 89 miniatures, painted by Magius, ''archipictor''. |

||

*''Beatus'' of San Salvador de Távara. Ca. 968 / 970. [[Madrid]]. Archivo Historico Nacional. Ms 1097 B (1240). Painted by Magius, finished after his death by his pupil Emeterius. |

*''Beatus'' of San Salvador de Távara. Ca. 968 / 970. [[Madrid]]. Archivo Historico Nacional. Ms 1097 B (1240). Painted by Magius, finished after his death by his pupil Emeterius. |

||

*''Beatus'' of Valcavado. Ca. 970. [[Valladolid]]. Biblioteca de la Universidad. Ms. 433 (ex ms 390). 97 miniatures extant. Painted by Oveco for the abbot Semporius. |

*''Beatus'' of Valcavado. Ca. 970. [[Valladolid]]. Biblioteca de la Universidad. Ms. 433 (ex ms 390). 97 miniatures extant. Painted by Oveco for the abbot Semporius. |

||

*[[Urgell Beatus|Urgell ''Beatus'']] of [[La Rioja (Spain)|Rioja]] or [[León, Spain|León]]. Ca. 975. Cathedral of [[La Seu d'Urgell]]. Archives. Ms. 26. 90 miniatures. |

*[[Urgell Beatus|Urgell ''Beatus'']] of [[La Rioja (Spain)|Rioja]] or [[León, Spain|León]]. Ca. 975. Cathedral of [[La Seu d'Urgell]]. Archives. Ms. 26. 90 miniatures. |

||

*[[Gerona Beatus |

*[[Gerona Beatus]] or ''Beatus'' of Távara]]. Ca. 975. Cathedral of [[Girona]]. Archives. Ms. 7. 260 x 400 mm. 280 leaves. 160 miniatures. Painted by Emeterius (pupil of Magius) and by the nun Ende. |

||

*''Beatus'' of San Millán. 2nd third of the 10th century. [[Madrid]]. Biblioteca Nacional. Ms. Vit. 14.1. |

*''Beatus'' of San Millán. 2nd third of the 10th century. [[Madrid]]. Biblioteca Nacional. Ms. Vit. 14.1. |

||

*''Beatus'' of [[León (Spain)|León]]. 1047. [[Madrid]]. Biblioteca Nacional. Ms. Vit. 14.2. Made for [[Ferdinand I of Castile|Ferdinand I]] and Queen Sancha. 267 x 361 mm. 312 leaves. 98 miniatures. Painted by Facundus. |

*''Beatus'' of [[León (Spain)|León]]. 1047. [[Madrid]]. Biblioteca Nacional. Ms. Vit. 14.2. Made for [[Ferdinand I of Castile|Ferdinand I]] and Queen Sancha. 267 x 361 mm. 312 leaves. 98 miniatures. Painted by Facundus. |

||

Revision as of 23:31, 11 December 2013

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2013) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (April 2010) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Commentary on the Apocalypse (Commentaria In Apocalypsin) was originally an eighth century work by the Spanish monk and theologian Beatus of Liébana. Today, it refers to any of the extant manuscript copies of this work, especially any of the 26 illuminated copies that have survived. It is often referred to simply as the Beatus. The historical significance of the Commentary is made even more pronounced since it included a world map, which offers a rare insight into the geographical understanding of the post-Roman world. Well-known copies include the Morgan, the Saint-Sever, the Gerona, the Osma and the Madrid (Vitr 14-1) Beatus codices.

Considered together, the Beatus codices are among the most important Spanish medieval manuscripts and have been the subject of extensive scholarly and antiquarian enquiry.

The Commentary on the Apocalypse (Commentaria In Apocalypsin)

The work consists of several prologues (which differ among the manuscripts) and one long summary section (the "Summa Dicendum") before the first book, an introduction to the second book, and 12 books of commentary, some long and some very short. Beatus states in its dedication to his friend Bishop Etherius that it is meant to educate his brother monks.

The work is structured around selections from previous Apocalypse commentaries and references by Tyconius (now mostly lost), St. Primasius of Hadrumentum, St. Caesarius of Arles, St. Apringius of Beja, and many others. There are also long extracts from the texts of the Fathers of the Church and Doctors of the Church, especially Augustine of Hippo (Saint Augustine), Ambrose of Milan (Saint Ambrose), Irenaeus of Lyons (Saint Irenaeus), [Pope Gregory I] (Pope St. Gregory the Great), Saint Jerome (Jerome of Stridon), and Isidore of Seville (Saint Isidore), as well as others. Some manuscripts add commentaries on the books of Ezekiel and Daniel by other authors, genealogical tables, and the like, but these are not strictly part of the Beatus.

The creative character of the Commentary comes from Beatus' writing of a wide-ranging catena of verses from nearly every book of the Bible, quotes of patristic commentary from many little known sources, and interstitial original comments by Beatus. His attitude is one of realism about church politics and human pettiness, hope and love towards everyday life even when it is difficult, and many homely similes from his own time and place. (For example, he compares evangelization to lighting fires for survival when caught far from home by a sudden mountain blizzard, and the Church to a Visigothic army with both generals and muleskinners.) His work is also a fruitful source for Spanish linguistics, as Beatus often alters words in his African Latin sources to the preferred synonyms in Hispanic Latin.[1] [3] [4] [5]

The message

After 711 AD, Spanish Christians found themselves being persecuted by Muslims. They could no longer practice their religion openly; bells and processions were forbidden; churches and monasteries were destroyed and were not reconstructed; persecutions often lead to bloody outcomes. The Apocalypse and the symbolism in it took on a different meaning. The beast, which had previously been believed to represent the Roman Empire, now became the Caliphate, and Babylon was no longer Rome, but Córdoba.

In continuity with previous commentaries written in the Tyconian tradition, and in continuity with St. Isidore of Seville and St. Apringius of Beja from just a few centuries before him, Beatus' Commentary on the Apocalypse focuses on the sinless beauty of the eternal Church, and on the tares growing among the wheat in the Church on Earth. Persecution from outside forces like pagan kings and heretics is mentioned, but it is persecution from fellow members of the Church that Beatus spends hundreds of pages. Anything critical of the Jews in the Bible is specifically said to have contemporary effect as a criticism of Christians, and particularly of monks and other religious; and a good deal of what is said about pagans is stated as meant as a criticism of Christians who worship their own interests more than God. Muslims are barely mentioned, except as references to Christian heresies include them. Revelation is a book about the Church's problems throughout all ages, not about history per se. In the middle of Book 4 of 12, Beatus does state his guess about the end-date of the world (801 AD, from the number of the Holy Spirit plus Alpha, as well as a few other calculations) although he warns people that it is folly to try to guess a date that even Jesus in the Bible claimed not to know.[1][2][3][4][5]

Copies of the manuscript

Principal copies

The more notable among the 31 Beatus manuscripts are :

- The Nájera fragment. 9th century. Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos.

- Beatus of the Monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla. Ca. 930. Madrid. Real Academia de la Historia. Ms. 33.

- Escorial Beatus of San Millán. Ca. 950 / 955. Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo. Ms. & II. 5. 225 x 355 mm. 151 leaves; 52 miniatures.

- Morgan Beatus or Beatus of San Miguel de Escalada. Ca. 960. Pierpont Morgan Library (New York). Ms 644. 280 x 380 mm. 89 miniatures, painted by Magius, archipictor.

- Beatus of San Salvador de Távara. Ca. 968 / 970. Madrid. Archivo Historico Nacional. Ms 1097 B (1240). Painted by Magius, finished after his death by his pupil Emeterius.

- Beatus of Valcavado. Ca. 970. Valladolid. Biblioteca de la Universidad. Ms. 433 (ex ms 390). 97 miniatures extant. Painted by Oveco for the abbot Semporius.

- Urgell Beatus of Rioja or León. Ca. 975. Cathedral of La Seu d'Urgell. Archives. Ms. 26. 90 miniatures.

- Gerona Beatus or Beatus of Távara]]. Ca. 975. Cathedral of Girona. Archives. Ms. 7. 260 x 400 mm. 280 leaves. 160 miniatures. Painted by Emeterius (pupil of Magius) and by the nun Ende.

- Beatus of San Millán. 2nd third of the 10th century. Madrid. Biblioteca Nacional. Ms. Vit. 14.1.

- Beatus of León. 1047. Madrid. Biblioteca Nacional. Ms. Vit. 14.2. Made for Ferdinand I and Queen Sancha. 267 x 361 mm. 312 leaves. 98 miniatures. Painted by Facundus.

- Beatus. 1086. Cathedral of El Burgo de Osma. Archives. Cod. 1. 225 x 360 mm. 166 leaves. 71 miniatures. Scribe: Petrus. Painter: Martinus.

- Saint-Sever Beatus of Saint-Sever (Landes). 1060 / 1070. Paris. Bibliothèque nationale. Ms. Lat. 8878.

- Beatus of Santo Domingo de Silos. 1091 / 1109. London. British Library. Ms. Add. 11695.

Later copies

- Rylands Beatus [R]: Manchester, John Rylands Library Latin MS 8), ca. 1175,

- Cardeña Beatus [Pc]: ca. 1180 and is dispersd between collections in Madrid (Museo Arqueológico Nacional and Colección Francisco de Zabálburu y Basabe), New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Girona (Museu d’Art de Girona). A facsimile edition by M. Moleiro Editor has gathered them all to recreate the original volume as it was.

- Beatus of Lorvão [L] written in 1189 in the monastery of St Mammas in Lorvão (Portugal); Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo in Lisbon.

- Arroyo Beatus [Ar] written in the 1st half of the 13th century in the region of Burgos, perhaps in the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña. Paris (Bibliothèque nationale) and New York (Bernard H. Breslauer Collection).

Gallery

-

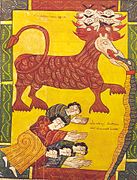

Escorial Beatus, f. 108v: Worship of the beast and dragon

-

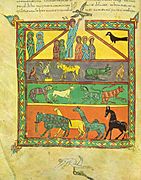

Osma Beatus, f. 139: The Frogs

-

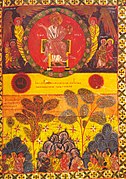

Facundus Beatus, f. 191v: The Dragon gives his power to the Beast

-

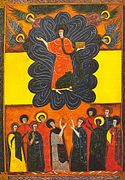

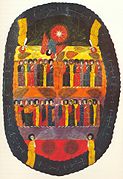

Urgell Beatus, f. 82v: Noah's Ark

-

The world map from the Saint-Sever Beatus measuring 37 X 57 cm. This was painted c. 1050 as an illustration to Beatus' work at the Abbey of Saint-Sever in Aquitaine, on the order of Gregori de Montaner, Abbot from 1028 to 1072

-

Valladolid Beatus, f. 120: The Angel of the Fifth Trumpet: "And the fifth angel sounded, and I saw a star fall from heaven unto the earth: and to him was given the key of the bottomless pit" (Revelation, 9.1)

-

Facundus Beatus, f. 224 (detail): "And the woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet, and decked with gold and precious stone and pearls, having in her hand a golden cup full of abominations, even the unclean things of her fornication, and upon her forehead a name written: «Mystery, Babylon the Great, the mother of the harlots and of the abominations of earth.»" (Revelation, 17.4-5)

-

Facundus Beatus, f. 186v: '"And there appeared a great wonder in Heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars: And she being with child cried, travailing in birth, and pained to be delivered. And there appeared another wonder in Heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads" (Revelation, 12.1-3)

-

Morgan Beatus, f. 112: The opening of the Sixth Seal: "And I beheld when he had opened the sixth seal, and, lo, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood" (Revelation, 6.12)

-

Facundus Beatus, f. 6v: "I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending, saith the Lord, which is, and which was, and which is to come, the Almighty." (Revelation, 1.8)

-

Facundus Beatus, f. 240: "And I saw heaven opened, and behold a white horse; and he that sat upon him was called «Faithful» and «True», and in righteousness he doth judge and make war. His eyes were as a flame of fire, and on his head were many crowns; and he had a name written, that no man knew, but he himself. And he was clothed with a vesture dipped in blood: and his name is called The Word of God." (Revelation, 19.11)

-

Osma Beatus, f. 151 The victorious Christ

-

Urgell Beatus, f. 209 (detail): Siege of Jerusalem by Nebudchadnezzar

-

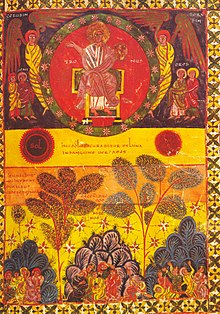

Facundus Beatus, f°43v, The great Theophany

-

Urgell Beatus, f°198v-199 The new Jerusalem, the river of life

-

Facundus Beatus, f°253v The new Jerusalem

-

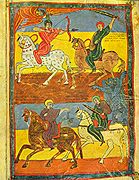

Beatus de Valladolid, f°93 The four horsemen

-

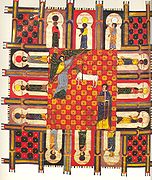

Facundus Beatus, f°135 The four horsemen

-

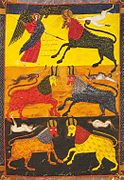

Facundus Beatus, f°171v The monstrous beasts

-

Facundus Beatus, f°145 The elect and the angels restraining the winds

References

- ^ In Apocalypsin. Ed. Florez, Madrid, 1770. The first known printed edition of the commentary. Latin.

- ^ Commentarius in Apocalypsin. (2 Vols.) Ed. E. Romero-Pose. Rome, 1985. The second critical edition of the commentary. Latin.

- ^ Tractatus in Apocalypsin. Ed. Gryson. (Vols. 107B and 107C, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina.) Brepols, 2012. The third critical edition of the commentary. Latin, with French introductory material. Also available in a French translation by Gryson, as part of the Sources Chretiennes series, but I've never seen it myself.

- ^ Beato de Liebana: Obras Completas y Complementarias, Vol. I. BAC, 2004. The commentary translated by Alberto del Campo Hernandez and Joaquin Gonzalez Echegaray. Side by side Spanish and Latin.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Apocalypse: The Illustrated Book of Revelation. No exegesis, but extensive full colour images from five different versions of the Beatus and the Bamberg Apocalypse.Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B008WAK9SS.

- Commentarius in Apocalypsin. Ed. Henry A. Sanders. American Academy of Rome, Rome, 1930. The first critical edition of the commentary. Latin. (May include English-language material; I've never seen it personally.)

- The Illustrated Beatus: a corpus of the illustrations of the commentary on the Apocalypse by John Williams. 5 Volumes. Harvey Miller and Brepols, 1994, 1998, 2000. Art books attempting to document all the Beatus illustrations in all surviving manuscripts. Due to expense, most illustrations are reproduced in black and white. Unfortunately, Williams was uninterested in Beatus' text, and thus spread some misconceptions about it; but his art scholarship and tenacity is amazing. His books' influence on most of this Wikipedia article is strong.

External links

- In Apocalypsin, 1770 edition of the Commentary. Latin.

- A selection of the most relevant Beatus

- Illuminations of Beatus

- Works of Beatus

- Miniatures from the Rylands Beatus