User:Chetvorno/work11: Difference between revisions

←Created page with ' = For Tesla coil = A '''Tesla coil''' is an electrical resonant transformer circuit invented by Nikola Tesla around 1891.<ref name="PBS">{{cite we...' |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 22:55, 14 March 2017

For Tesla coil

A Tesla coil is an electrical resonant transformer circuit invented by Nikola Tesla around 1891.[1] It is used to produce high-voltage, low-current, high frequency alternating-current electricity.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] Tesla experimented with a number of different configurations consisting of two, or sometimes three, coupled resonant electric circuits.

Tesla used these coils to conduct innovative experiments in electrical lighting, phosphorescence, X-ray generation, high frequency alternating current phenomena, electrotherapy, and the transmission of electrical energy without wires. Tesla coil circuits were used commercially in sparkgap radio transmitters for wireless telegraphy until the 1920s,[1][9][10][11][12][13] and in medical equipment such as electrotherapy and violet ray devices. Today their main use is for entertainment and educational displays, although small coils are still used today as leak detectors for high vacuum systems.[8]

Operation

A Tesla coil is a radio frequency oscillator that drives an air-core double-tuned resonant transformer to produce high voltages at low currents.[9][14][15][16][17][18] Tesla's original circuits as well as most modern coils use a simple spark gap to excite oscillations in the tuned transformer. More sophisticated designs use transistor or thyristor[14] switches or vacuum tube electronic oscillators to drive the resonant transformer. These are described in later sections.

Tesla coils can produce output voltages from 50 kilovolts to several million volts for large coils.[14][16][18] The alternating current output is in the low radio frequency range, usually between 50 kHz and 1 MHz.[16][18] Although some oscillator-driven coils generate a continuous alternating current, most Tesla coils have a pulsed output;[14] the high voltage consists of a rapid string of pulses of radio frequency alternating current.

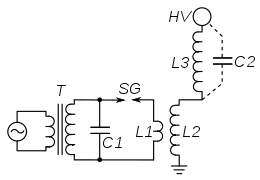

The common spark-excited Tesla coil circuit, shown below, consists of these components:[15][19]

- A high voltage supply transformer (T), to step the AC mains voltage up to a high enough voltage to jump the spark gap. Typical voltages are between 5 and 30 kilovolts (kV).[19]

- A capacitor (C1) that forms a tuned circuit with the primary winding L1 of the Tesla transformer

- A spark gap (SG) that acts as a switch in the primary circuit

- The Tesla coil (L1, L2), an air-core double-tuned resonant transformer, which generates the high output voltage.

- Optionally, a capacitive electrode (top load) (E) in the form of a smooth metal sphere or torus attached to the secondary terminal of the coil. Its large surface area suppresses premature corona discharge and streamer arcs, increasing the Q factor and output voltage.

Resonant transformer

The specialized transformer coil used in the Tesla circuit, called a resonant transformer, oscillation transformer, or RF transformer, functions differently from an ordinary transformer used in AC power circuits.[20][21][22] While an ordinary transformer is designed to transfer energy efficiently from primary to secondary winding, the resonant transformer is also designed to store electrical energy. Each winding has a capacitance across it and functions as an LC circuit (resonant circuit, tuned circuit), storing oscillating electrical energy, analogously to a tuning fork. The primary winding (L1) consisting of a relatively few turns of heavy copper wire or tubing, is connected to a capacitor (C1) through the spark gap (SG).[14][15] The secondary winding (L2) consists of many turns (hundreds to thousands) of fine wire on a hollow cylindrical form inside the primary. The secondary is not connected to an actual capacitor, but it also functions as an LC circuit, the inductance (L2) resonates with (C2), the sum of the stray parasitic capacitance between the windings of the coil, and the capacitance of the toroidal metal electrode attached to the high voltage terminal. The primary and secondary circuits are tuned so they resonate at the same frequency, they have the same resonant frequency. This allows them to exchange energy, so the oscillating current alternates back and forth between the primary and secondary coils.

The peculiar design of the coil is dictated by the need to achieve low resistive energy losses (high Q factor) at high frequencies,[16] which results in the largest secondary voltages:

- Ordinary power transformers have an iron core to increase the magnetic coupling between the coils. However at high frequencies an iron core causes energy losses due to eddy currents and hysteresis, so it is not used in the Tesla coil.[22]

- Ordinary transformers are designed to be "tightly coupled". Due to the iron core and close proximity of the windings, they have a high mutual inductance (M), the coupling coefficient is close to unity 0.95 - 1.0, which means almost all the magnetic field of the primary winding passes through the secondary.[20][22] The Tesla transformer in contrast is "loosely coupled",[14][22] the primary winding is larger in diameter and spaced apart from the secondary,[15] so the mutual inductance is lower and the coupling coefficient is only 0.05 to 0.2; meaning only 5% to 20% of the magnetic field of each coil passes through the other.[14][19] This slows the exchange of energy between the primary and secondary coils, which allows the oscillating energy to stay in the secondary circuit longer before it returns to the primary and begins dissipating in the spark.

- Each winding is also limited to a single layer of wire, which reduces proximity effect losses. The primary carries very high currents. Since high frequency current mostly flows on the surface of conductors due to skin effect, it is made of copper tubing or strip with a large surface area to reduce resistance, and its turns are spaced apart, which reduces proximity effect losses.[23][24]

The output circuit can have two forms:

- Unipolar - One end of the secondary winding is connected to a single high voltage terminal, the other end is grounded. This type is used in modern coils designed for entertainment. The primary winding is located near the bottom, low potential end of the secondary, to minimize arcs between the windings. Since the ground (Earth) serves as the return path for the high voltage, streamer arcs from the terminal tend to jump to any nearby grounded object.

- Bipolar - Neither end of the secondary winding is grounded, and both are brought out to high voltage terminals. The primary winding is located at the center of the secondary coil, equidistant between the two high potential terminals, to discourage arcing.

Operation cycle

The circuit operates in a rapid repeating cycle in which the supply transformer (T) charges the primary capacitor (C1) up, which then discharges in a spark through the spark gap, creating a brief pulse of oscillating current in the primary circuit which excites a high oscillating voltage across the secondary:[17][19][22][25]

- Current from the supply transformer (T) charges the capacitor (C1) to a high voltage.

- When the voltage across the capacitor reaches the breakdown voltage of the spark gap (SG) a spark starts, reducing the spark gap resistance to a very low value. This completes the primary circuit and current from the capacitor flows through the primary coil (L1). The current flows rapidly back and forth between the plates of the capacitor through the coil, generating radio frequency oscillating current in the primary circuit at the circuit's resonant frequency.

- The oscillating magnetic field of the primary winding induces an oscillating current in the secondary winding (L2), by Faraday's law of induction. Over a number of cycles, the energy in the primary circuit is transferred to the secondary. The total energy in the tuned circuits is limited to the energy originally stored in the capacitor C1, so as the oscillating voltage in the secondary increases in amplitude ("ring up") the oscillations in the primary decrease to zero ("ring down"). Although the ends of the secondary coil are open, it also acts as a tuned circuit due to the capacitance (C2), the sum of the parasitic capacitance between the turns of the coil plus the capacitance of the toroid electrode E. Current flows rapidly back and forth through the secondary coil between its ends. Because of the small capacitance, the oscillating voltage across the secondary coil which appears on the output terminal is much larger than the primary voltage.

- The secondary current creates a magnetic field that induces voltage back in the primary coil, and over a number of additional cycles the energy is transferred back to the primary. This process repeats, the energy shifting rapidly back and forth between the primary and secondary tuned circuits. The oscillating currents in the primary and secondary gradually die out ("ring down") due to energy dissipated as heat in the spark gap and resistance of the coil.

- When the current through the spark gap is no longer sufficient to keep the air in the gap ionized, the spark stops ("quenches"), terminating the current in the primary circuit. The oscillating current in the secondary may continue for some time.

- The current from the supply transformer begins charging the capacitor C1 again and the cycle repeats.

This entire cycle takes place very rapidly, the oscillations dying out in a time of the order of a millisecond. Each spark across the spark gap produces a pulse of damped sinusoidal high voltage at the output terminal of the coil. Each pulse dies out before the next spark occurs, so the coil generates a string of damped waves, not a continuous sinusoidal voltage.[17] The high voltage from the supply transformer that charges the capacitor is a 50 or 60 Hz sine wave. Depending on how the spark gap is set, usually one or two sparks occur at the peak of each half-cycle of the mains current, so there are more than a hundred sparks per second. Thus the spark at the spark gap appears continuous, as do the high voltage streamers from the top of the coil.

The supply transformer (T) secondary winding is connected across the primary tuned circuit. It might seem that the transformer would be a leakage path for the RF current, damping the oscillations. However its large inductance gives it a very high impedance at the resonant frequency, so it acts as an open circuit to the oscillating current. If the supply transformer has inadequate leakage inductance, radio frequency chokes are placed in its secondary leads to block the RF current.

Oscillation frequency

To produce the largest output voltage, the primary and secondary tuned circuits are adjusted to resonance with each other. The resonant frequencies of the primary and secondary circuits, and , are determined by the inductance and capacitance in each circuit[16][17][20]

Generally the secondary is not adjustable, so the primary circuit is tuned, usually by a moveable tap on the primary coil L1, until it resonates at the same frequency as the secondary

Thus the condition for resonance between primary and secondary is

The resonant frequency of Tesla coils is in the low radio frequency (RF) range, usually between 50 kHz and 1 MHz. However, because of the impulsive nature of the spark they produce broadband radio noise, and without shielding can be a significant source of RFI, interfering with nearby radio and television reception.

Output voltage

In a resonant transformer the high voltage is produced by resonance; the output voltage is not proportional to the turns ratio, as in an ordinary transformer.[22][26] It can be calculated approximately from conservation of energy. At the beginning of the cycle, when the spark starts, all of the energy in the primary circuit is stored in the primary capacitor . If is the voltage at which the spark gap breaks down, which is usually close to the peak output voltage of the supply transformer T, this energy is

During the "ring up" this energy is transferred to the secondary circuit. Although some is lost as heat in the spark and other resistances, in modern coils, over 85% of the energy ends up in the secondary.[17] At the peak () of the secondary sinusoidal voltage waveform, all the energy in the secondary is stored in the capacitance between the ends of the secondary coil

Assuming no energy losses, . Substituting into this equation and simplifying, the peak secondary voltage is[16][17][22]

The second formula above is derived from the first using .[22] Since the capacitance of the secondary coil is very small compared to the primary capacitor, the primary voltage is stepped up to a high value.[17]

It might seem that the output voltage could be increased indefinitely by reducing and . However, as the output voltage increases, it reaches the point where the air next to the high voltage terminal ionizes and corona discharges, brush discharges and streamer arcs break out from the secondary coil. This happens when the electric field strength reaches about 30 kV per centimeter, and occurs first at sharp points and edges on the high voltage terminal. The resulting energy loss damps the oscillation, so the above lossless model is no longer accurate, and the voltage does not reach the theoretical maximum above.[17][22][23]

The top load or "toroid" electrode

Most unipolar Tesla coil designs have a spherical or toroidal shaped metal electrode on the high voltage terminal. Although the "toroid" increases the secondary capacitance, which tends to reduce the peak voltage, its main effect is that its large diameter curved surface reduces the potential gradient (electric field) at the high voltage terminal, increasing the voltage threshold at which corona and streamer arcs form. Suppressing premature air breakdown and energy loss allows the voltage to build to higher values on the peaks of the waveform, creating longer, more spectacular streamers.[22]

If the top electrode is large and smooth enough, the electric field at its surface may never get high enough even at the peak voltage to cause air breakdown, and air discharges will not occur. Some entertainment coils have a sharp "spark point" projecting from the torus to start discharges.

Types

The term "Tesla coil" is applied to a number of high voltage resonant transformer circuits.

Tesla coil circuits can be classified by the type of "excitation" they use, what type of circuit is used to apply current to the primary winding of the resonant transformer:[27][28]

- Spark-excited or Spark Gap Tesla Coil (SGTC) - This type uses a spark gap to switch pulses of current through the primary, exciting oscillation in the transformer. This pulsed (disruptive) drive creates a pulsed high voltage output. Spark gaps have disadvantages due to the high primary currents they must handle. They produce a very loud noise while operating, noxious ozone gas, and high temperatures which often require a cooling system. The energy dissipated in the spark also reduces the Q factor and the output voltage.

- Static spark gap - This is the most common type, which was described in detail in the previous section. It is used in most entertainment coils. An AC voltage from a high voltage supply transformer charges a capacitor, which discharges through the spark gap. The spark rate is not adjustable but is determined by the line frequency. Multiple sparks may occur on each half-cycle, so the pulses of output voltage may not be equally-spaced.

- Static triggered spark gap - Commercial and industrial circuits often apply a DC voltage from a power supply to charge the capacitor, and use high voltage pulses generated by an oscillator applied to a triggering electrode to trigger the spark.[14] This allows control of the spark rate and exciting voltage. Commercial spark gaps are often enclosed in an insulating gas atmosphere such as sulfur hexafluoride, reducing the length and thus the energy loss in the spark.

- Rotary spark gap - These use a spark gap consisting of electrodes around the periphery of a wheel rotated by a motor, which create sparks when they pass by a stationary electrode. Tesla used this type on his big coils, and they are used today on large entertainment coils. The rapid separation speed of the electrodes quenches the spark quickly, allowing "first notch" quenching, making possible higher voltages. The wheel is usually driven by a synchronous motor, so the sparks are synchronized with the AC line frequency, the spark occurring at the same point on the AC waveform on each cycle, so the primary pulses are repeatable.

- Switched or Solid State Tesla Coil (SSTC) - These use power semiconductor devices, usually thyristors or transistors such as MOSFETs or IGBTs,[14] to switch pulses of current from a DC power supply through the primary winding. They provide pulsed (disruptive) excitation without the disadvantages of a spark gap: the loud noise and high temperatures. They allow fine control of the voltage, pulse rate and exciting waveform. This type is used in most commercial, industrial, and research applications[14] as well as higher quality entertainment coils.

- Single resonant solid state Tesla coil - In this circuit the primary does not have a capacitor and so is not a tuned circuit; only the secondary is. The pulses of current to the primary from the switching transistors excite resonance in the secondary tuned circuit. Single tuned SSTCs are simpler, but don't have as high a Q and cannot produce as high voltage from a given input power as the DRSSTC.

- Dual Resonant Solid State Tesla Coil (DRSSTC) - A double tuned Tesla transformer driven by solid state switching supply. This functions similarly to the double tuned spark excited circuits.

- Singing Tesla coil or musical Tesla coil - This is a Tesla coil which can be played like a musical instrument, with its high voltage discharges reproducing simple musical tones. The drive current pulses applied to the primary are modulated at an audio rate by a solid state "interrupter" circuit, causing the arc discharge from the high voltage terminal to emit sounds. Only tones and simple chords have been produced so far; the coil cannot reproduce complex music. The sound output is controlled by a keyboard or MIDI file applied to the circuit through a MIDI interface. Two modulation techniques have been used: AM (amplitude modulation of the exciting voltage) and PFM (pulse-frequency modulation). These are mainly built as novelties for entertainment.

- Continuous wave - In these the transformer is driven by a feedback oscillator, which applies a sinusoidal current to the transformer. The primary tuned circuit serves as the tank circuit of the oscillator, and the circuit resembles a radio transmitter. Unlike the previous circuits which generate a pulsed output, they generate a continuous sine wave output. Power vacuum tubes are often used as active devices instead of transistors because they are more robust and tolerant of overloads. In general, continuous excitation produces lower output voltages from a given input power than pulsed excitation.

Tesla circuits can also be classified by how many coils (inductors) they contain:[29][30]

- Two coil or double-resonant circuits - Virtually all present Tesla coils use the two coil resonant transformer, consisting of a primary winding to which current pulses are applied, and a secondary winding that produces the high voltage, invented by Tesla in 1891. The term "Tesla coil" normally refers to these circuits.

- Three coil, triple-resonant, or magnifier circuits - These are circuits with three coils, based on Tesla's "magnifying transmitter" circuit which he began experimenting with sometime before 1898 and installed in his Colorado Springs lab 1899-1900, and patented in 1902.[31][32][33] They consist of a two coil air-core step-up transformer similar to the Tesla transformer, with the secondary connected to a third coil not magnetically coupled to the others, called the "extra" or "resonator" coil, which is series-fed and resonates with its own capacitance. The presence of three energy-storing tank circuits gives this circuit more complicated resonant behavior. It is the subject of research, but has been used in few practical applications.

History

Nikola Tesla patented the Tesla coil circuit April 25, 1891.[37][38] and first publicly demonstrated it May 20, 1891 in his lecture "Experiments with Alternate Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination" before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers at Columbia College, New York.[39][40][41] Although Tesla patented many similar circuits during this period, this was the first that contained all the elements of the Tesla coil: high voltage primary transformer, capacitor, spark gap, and air core "oscillation transformer".

Invention

During the Industrial Revolution the electrical industry exploited direct current (DC) and low frequency alternating current (AC), but not much was known about frequencies above 20 kHz, what are now called radio frequencies. In 1887, four years previously, Heinrich Hertz had discovered Hertzian waves (radio waves), electromagnetic waves which oscillated at very high frequencies.[43][44][45] This attracted much attention, and a number of researchers began experimenting with high frequency currents.

Tesla's background was in the new field of alternating current power systems, so he understood transformers and resonance.[44][41] In 1888 he set up a laboratory at 33 South Fifth Avenue, New York, where he researched high frequencies, initially repeating Hertz's experiments.

Tesla first developed alternators as sources of high frequency current, but by 1890 found they were limited to frequencies of about 20 kHz.[41] In search of higher frequencies he turned to spark-excited resonant circuits.[44] Tesla's innovation was in applying resonance to transformers.[46] Inductors and transformers functioned differently at high frequencies than at the low frequencies used in power systems; the iron core in conventional transformers caused energy losses due to eddy currents and hysteresis.[44] Tesla[36] [46][41] and Elihu Thomson[35][47][48] independently developed a new type of transformer without an iron core, the "oscillation transformer".

In 1891 Tesla was developing a "wireless" lighting system, with a gas discharge light bulb that would glow in an electrostatic field from a high voltage, high frequency power source.[44][41] He investigated many resonant transformer circuits.[37] He found that high voltages could be generated by resonant transformers in which the primary winding with few turns is in a "closed" tuned circuit with a capacitor and spark gap, and the secondary winding, with many turns, is an "open" circuit.[46][41] High voltages are produced when the primary and secondary circuits are in resonance.

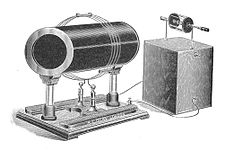

-

One of Tesla's early coils at his New York lab in 1892, with a conical secondary.

Tesla was not the first to invent this circuit.[52][48] Henry Rowland built a spark-excited resonant transformer circuit (above) in 1889[35] and Elihu Thomson had experimented with similar circuits in 1890, including one which could produce 64 inch (1.6 m) sparks,[42][53][54] [34] and other sources confirm Tesla was not the first.[47][55][48] However he was the first to see practical applications for it and patent it. Tesla did not perform detailed mathematical analyses of the circuit, relying instead on trial and error and his intuitive understanding of resonance.[41] He even realized that the secondary coil functioned as a quarter-wave resonator; he specified the length of the wire in the secondary coil must be a quarter wavelength at the resonant frequency.[56][41] The first mathematical analyses of the circuit were done by Anton Oberbeck (1895)[57][48] and Paul Drude (1904).[58][37]

Tesla's demonstrations

A charismatic showman and self-promoter, in 1891-1893 Tesla used the Tesla coil in dramatic public lectures demonstrating the new science of high voltage, high frequency electricity.[59] The radio frequency AC electric currents produced by a Tesla coil did not behave like the DC or low frequency AC current scientists of the time were familiar with. In lectures at Columbia College May 20, 1891,[39] scientific societies in Britain and France during a 1892 European speaking tour,[61] the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia in February 1893, and the National Electric Light Association, St. Louis in March 1893,[62] he impressed audiences with spectacular brush discharges and streamers, heated iron by induction heating, showed RF current could pass through insulators and be conducted by a single wire without a return path, and powered light bulbs and motors without wires.[59] He demonstrated that high frequency currents often did not cause the sensation of electric shock, applying hundreds of thousands of volts to his own body,[63] causing his body to light up with a glowing corona discharge in the darkened room. These lectures made Tesla internationally famous.[64][45]

Wireless power experiments

Tesla employed the Tesla coil in his efforts to achieve wireless power transmission,[66] his lifelong dream. In the period 1891 to 1900 he used it to perform some of the first experiments in wireless power,[67][68][69] transmitting radio frequency power across short distances by inductive coupling between coils of wire.[68][69][70] In his early 1890s demonstrations such as those before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers[70] and at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago he lit light bulbs from across a room.[69] He found he could increase the distance by using a receiving LC circuit tuned to resonance with the Tesla coil's LC circuit,[46] transferring energy by resonant inductive coupling.[69] At his Colorado Springs laboratory during 1899-1900, by using voltages of the order of 10 million volts generated by his enormous magnifying transmitter coil (described below), he was able to light three incandescent lamps at a distance of about 100 feet (30 m).[5][71] Today the resonant inductive coupling discovered by Tesla is a familiar concept in electronics, widely used in IF transformers and short range wireless power transmission systems[69][72] such as cellphone charging pads.

It is now understood that inductive and capacitive coupling are "near-field" effects,[69] so they cannot be used for long-distance transmission.[73][74][75] However, Tesla was obsessed with developing a long range wireless power transmission system which could transmit power from power plants directly into homes and factories without wires, described in a visionary June 1900 article in Century Magazine; "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy".[76] He claimed to be able to transmit power on a worldwide scale, using a method that involved conduction through the Earth and atmosphere.[65][77][78][66][79] Tesla believed that the entire Earth could act as an electrical resonator, and that by driving current pulses into the Earth at its resonant frequency from a grounded Tesla coil with an elevated capacitance, the potential of the Earth could be made to oscillate, creating global standing waves, and this alternating current could be received with a capacitive antenna tuned to resonance with it at any point on Earth.[80][81][82][77] Another of his ideas was that transmitting and receiving terminals could be suspended in the air by balloons at 30,000 feet (9,100 m) altitude, where the air pressure is lower.[81][49][65][66] At this altitude, he thought, the rarefied air would be electrically conductive, allowing electricity to be sent at high voltages (hundreds of millions of volts) over long distances. Tesla envisioned building a global network of wireless power stations, which he called his "World Wireless System", which would transmit both information and electric power to everyone on Earth.

Magnifying transmitter

Tesla's wireless research required increasingly high voltages, and he had reached the limit of the voltages he could generate within the space of his New York lab. Between 1899-1900 he built a laboratory in Colorado Springs and performed experiments on wireless transmission there.[32] The Colorado Springs laboratory had one of the largest Tesla coils ever built, which Tesla called a "magnifying transmitter" as it was intended to transmit power to a distant receiver.[83] With an input power of 300 kilowatts it could produce potentials of the order of 10 million volts,[32][80] at frequencies of 50-150 kHz, creating huge "lightning bolts" reportedly up to 135 feet long.[16] When Tesla first turned it on, it caused an overload which set fire to the alternator of the Colorado Springs power company, destroying it, and Tesla had to rebuild the alternator.[16]

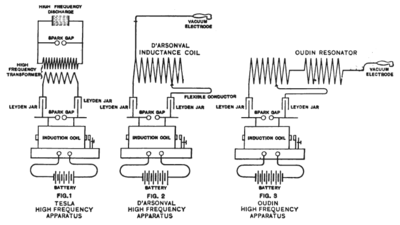

In the magnifying transmitter, Tesla used a modified design (see circuit) which he had been experimenting with since before 1898 and patented in 1902,[31][26] different from his previous double-tuned circuits. In addition to the primary (L1) and secondary (L2) coils, it had a third coil (L3) which he called the "extra" coil, not magnetically coupled to the others, attached to the top terminal of the secondary.[32] When driven by the secondary it produced high voltage by resonance, being adjusted to resonate with its own parasitic capacitance (C2)[32] The use of a series-fed resonator coil to generate high voltages was independently discovered by Paul Marie Oudin in 1893 and employed in his Oudin coil.[84]

The Colorado Springs apparatus consisted of a 51 foot (15.5 m) diameter Tesla transformer composed of a secondary winding (L2) of 50 turns of heavy wire wound on an 8 foot (2.4 m) high circular "fence" around the periphery of the lab, and a single-turn primary (L1) buried in the ground under it.[85][86] The primary was connected to a bank of oil capacitors (C1) to make a tuned circuit, with a rotary spark gap (SG), powered by 20 to 40 kilovolts from a powerful utility step-up transformer (T). The top of the secondary was connected to the 100-turn 8 ft (2.4 m) diameter "extra" or "resonator" coil (L3) in the center of the room. It's high voltage end was connected to a telescoping 143 foot (43.6 m) "antenna" rod with a 30 inch (1 m) metal ball on top which could project through the roof of the lab.

Wardenclyffe tower

In 1901, convinced his wireless theories were correct, Tesla with financing from banker J. P. Morgan began construction of a high-voltage wireless station, now called the Wardenclyffe Tower, at Shoreham, New York.[77][87] Although it was built as a transatlantic radiotelegraphy station, Tesla also intended it to transmit electric power without wires as a prototype transmitter for his proposed "World Wireless System".[83] Essentially an enormous Tesla coil, it consisted of a powerhouse with a 187 foot (57 m) tower topped by a 68 foot (21 m) diameter metal dome capacitive electrode.[83] Due to Tesla's secrecy there is little detailed information on how it was supposed to work.

By 1904 his investors had pulled out and the facility was never completed; it was torn down in 1916.[78][59] Although Tesla seems to have believed his wireless power ideas were proven,[88] he had a history of making claims that he had not confirmed by experiment,[89][44] and there seems to be no evidence that he ever transmitted significant power beyond the short-range demonstrations above.[90][68][88][44][91][92][93][94] The few reports of long-distance power transmission by Tesla are not from reliable sources. For example, a widely repeated myth is that in 1899 he wirelessly lit 200 light bulbs at a distance of 26 miles (42 km).[90][88] There is no independent confirmation of this supposed demonstration;[90][88] Tesla did not mention it,[88] and it does not appear in his laboratory notes.[80][95] It originated in 1944 from Tesla's first biographer, John J. O'Neill,[5] who said he pieced it together from "fragmentary material... in a number of publications".[96]

In the 100 years since, others such as Robert Golka[85][97][98] have built equipment similar to Tesla's, but long distance power transmission has not been demonstrated,[99][69][5][88] and the scientific consensus is his World Wireless system would not have worked.[13][67][68][78][88][91][100][94] Contemporary scientists point out that while Tesla's coils (with appropriate antennas) can function as radio transmitters, transmitting energy in the form of radio waves, the frequency he used, around 150 kHz, is far too low for practical long range power transmission.[68][88][92] At these wavelengths the radio waves spread out in all directions and cannot be focused on a distant receiver.[67][68][88][91][100] Tesla's world power transmission scheme remains today what it was in Tesla's time: a bold, fascinating dream.[78][91]

Use in radio

- "[The Tesla coil] was invented not for wireless but for making vacuum lamps glow without external electrodes, and it later played a principal part in other hands in the operation of big spark stations." --William H. Eccles, 1933[103]

One of the largest applications of the Tesla coil circuit was in early radio transmitters called spark gap transmitters. The first radio wave generators, invented by Heinrich Hertz in 1887, were spark gaps connected directly to antennas, powered by induction coils.[104][105] [45] Because they lacked a resonant circuit, these transmitters produced highly damped radio waves. As a result their transmissions occupied an extremely wide bandwidth of frequencies. When multiple transmitters were operating in the same area their frequencies overlapped and they interfered with one another, causing garbled reception. There was no way for a receiver to select one signal over another.[105][104]

In 1892 William Crookes, a friend of Tesla, had given a lecture[106] on the uses of radio waves in which he suggested using resonance to reduce the bandwidth in transmitters and receivers. By using resonant circuits, different transmitters could be "tuned" to transmit on different frequencies. With narrower bandwidth, separate transmitter frequencies would no longer overlap, so a receiver could receive a particular transmission by "tuning" its resonant circuit to the same frequency as the transmitter.[104][45][102] This is the system used in all modern radio.

With an appropriate wire antenna, the Tesla coil circuit could function as such a narrow bandwidth radio transmitter.[9][47][16][1] In his March 1893 St. Louis lecture,[62] Tesla demonstrated a wireless system that was the first use of tuned circuits in radio, although he used it for wireless power transmission, not radio communication.[64][45][107][102][108][109] A grounded spark-excited capacitor-tuned Tesla transformer attached to an elevated wire antenna transmitted radio waves, which were received across the room by a wire antenna attached to a receiver consisting of a second grounded resonant transformer tuned to the transmitter's frequency, which lighted a Geissler tube.[110][104][102][109] This system, patented by Tesla September 2, 1897,[65] was the first use of the "four circuit" concept later claimed by Marconi.[111][109][64][108] However, Tesla was mainly interested in wireless power and never developed a practical radio communication system.[88][7][110][104] In fact, he never believed that radio waves could be used for practical communication, instead clinging to an erroneous theory that radio communication was due to currents in the Earth.[112]

Practical radiotelegraphy communication systems were developed by Guglielmo Marconi beginning in 1895. By 1897 the advantages of narrow-bandwidth (lightly damped) systems noted by Crookes were recognized, and resonant circuits, capacitors and inductors, were incorporated in transmitters and receivers.[107] The "closed primary, open secondary" resonant transformer circuit used by Tesla proved a superior transmitter,[108] because the loosely-coupled transformer partially isolated the oscillating primary circuit from the energy-radiating antenna circuit, reducing the damping, allowing it to produce long "ringing" waves which had a narrower bandwidth.[48][47][104] Versions of the circuit were patented by Marconi,[101][108] John Stone Stone[113] and Oliver Lodge,[114] and were widely used in radio for twenty years.[45][107][66][104][102] In 1906 Max Wien invented the quenched or "series" spark gap, which extinguished the spark after the energy had been transferred to the secondary, allowing the secondary to oscillate freely after that, reducing damping and bandwith still more.

Although their damping had been reduced as much as possible, spark transmitters still produced damped waves which had a wide bandwidth, creating interference with other transmitters. Around 1920 they became obsolete, superseded by vacuum tube transmitters which generated continuous waves at a single frequency, which could also be modulated to carry sound. Tesla's resonant transformer continued to be used in vacuum tube transmitters and receivers, and is a key component in radio to this day.[13]

During the "spark era" the radio engineering profession gave credit to Tesla,[104] his circuit became known as the "Tesla coil" or "Tesla transformer".[45][47][11] However Tesla did not benefit financially, due to competing patent claims. Marconi had claimed rights to the "closed primary open secondary" transmitter circuit in his controversial 1900 "four circuit" wireless patent.[101][111][108][66][102] Tesla sued Marconi in 1915 for patent infringement, but didn't have the resources to pursue the action.[104][108][107][66] However in 1943, in a separate suit brought by the Marconi Company against the US government for use of its patents in WW1, the US Supreme Court invalidated Marconi's 1900 patent claim to the "four circuit" concept.[115][45][66][102][12] The ruling cited the prior patents of Tesla, Lodge, and Stone,[104][45] but did not decide which of these parties had rights to the circuit.[66][108][102] Of course by this time the issue was moot; the patent had expired in 1915 and spark transmitters had long been obsolete.

Although there is some disagreement over the role Tesla himself played in the invention of radio,[116][45][66][12] sources agree on the importance of his circuit in early radio transmitters.[102][25][16][1][108][104][13] From a modern perspective, most spark transmitters could be regarded as Tesla coils.[16][9]

Use in medicine

Tesla had observed as early as 1891 that high frequency currents above 10 kHz did not cause the sensation of electric shock, and in fact currents that would be lethal at lower frequencies could be passed through the body without apparent harm.[118][119][120] He experimented on himself, passing currents from his coils through his body, and claimed it alleviated depression. He was one of the first to observe the heating effect of high frequency currents on the body, the basis of diathermy.[121][122] During his highly-publicized early 1890s demonstrations he passed hundreds of thousands of volts through his body.[63] With characteristic flamboyance he called electricity "the greatest of all doctors" and suggested burying wires under classrooms so its stimulating effect would improve performance of "dull" schoolchildren.[122][123] Tesla wrote a pioneering paper in 1898 on the medical uses of high frequency currents[119][124][120] but did no further work on the subject.

A few other researchers were also experimentally applying high frequency currents to the body at this time.[125][126][127][35][128] Elihu Thomson, the co-inventor of the Tesla coil, was one, so in medicine the Tesla coil became known as the "Tesla-Thomson apparatus".[35] In France, from 1889 physician and pioneering biophysicist Jacques d'Arsonval had been documenting the physiological effects of high frequency current on the body, and had made the same discoveries as Tesla.[129][121][128] During his 1892 European trip Tesla met with D'Arsonval and was flattered to find they were using similar circuits. D'Arsonval's spark-excited resonant circuits (above) did not produce as high voltage as the Tesla transformer.[35] In 1893 French physician Paul Marie Oudin added a "resonator" coil to the D'Arsonval circuit to create the high voltage Oudin coil,[128][130] a circuit very similar to the Tesla coil, which was widely used for treating patients in Europe.[35]

During this period, people were fascinated by the new technology of electricity, and many believed it had miraculous curative or "vitalizing" powers.[131] Medical ethics were also looser, and doctors could experiment on their patients. By the turn of the century, application of high voltage, "high frequency" currents to the body had become part of a Victorian era medical field, part legitimate experimental medicine and part quack medicine,[120] called electrotherapy.[131][84][125] Manufacturers produced medical apparatus to generate "Tesla currents", "D'Arsonval currents", and "Oudin currents" for physicians. In electrotherapy, a pointed electrode attached to the high voltage terminal of the coil was held near the patient, and the luminous brush discharges from it (called "effluves") were applied to parts of the body to treat a wide variety of medical conditions. In order to apply the electrode directly to the skin, or tissues inside the mouth, anus or vagina, a "vacuum electrode" was used, consisting of a metal electrode sealed inside a partially evacuated glass tube, which produced a dramatic violet glow. The glass wall of the tube and the skin surface formed a capacitor which limited the current to the patient, preventing discomfort. These "violet ray" wands were later sold as a quack home medical device.[132][133]

The popularity of electrotherapy peaked after World War 1,[121][131] but by the 1920s authorities began to crack down on fraudulent medical treatments, and electrotherapy largely became obsolete. A part of the field that survived was diathermy, the application of high frequency current to heat body tissue.[121][128] By 1930 "long wave" (0.5~2 MHz) Tesla coil diathermy machines were being replaced by "short wave" (10~100 MHz) vacuum tube diathermy machines,[121][128] but Tesla coils continued to be used in both diathermy[121] and quack medical devices like violet ray[132] until World War 2.

During the 1920s and 30s all unipolar (single terminal) high voltage medical coils came to be called Oudin coils, so today's unipolar Tesla coils are sometimes referred to as "Oudin coils".[134]

Use in show business

The Tesla coil's spectacular displays of sparks, and the fact that its currents could pass through the human body without causing electric shock, led to its use in the entertainment business.

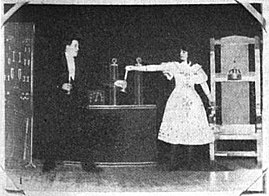

In the early 20th century it appeared in traveling carnivals, freak shows and circus and carnival sideshows, which often had an act in which a performer would pass high voltages through his body[63][137][135] [138][139] Performers such as "Dr. Resisto", "The Human Dynamo", "Electrice", "The Great Volta", and "Madamoiselle Electra" would have their body connected to the high voltage terminal of a hidden Tesla coil, causing sparks to shoot from their fingertips and other parts of their body, and Geissler tubes to light up when held in their hand or even brought near them.[136][140] They could also light candles or cigarettes with their fingers.[135] Although they didn't usually cause electric shocks, RF arc discharges from the bare skin could cause painful burns; to prevent them performers sometimes wore metal thimbles on their fingertips[135] (Rev. Moon, center image above, is using them). These acts were extremely dangerous and could kill the performer if the Tesla coil was misadjusted.[138] In carny lingo this was called an "electric chair act" because it often included a spark-laced "electrocution" of the performer in an electric chair,[138][139] exploiting public fascination with this exotic new method of capital punishment, which had become the United States' dominant method of execution around 1900. Today entertainers still perform high voltage acts with Tesla coils,[141][142] but modern bioelectromagnetics has brought a new awareness of the hazards of Tesla coil currents, and allowing them to pass through the body is today considered extremely dangerous.

Tesla coils were also used as dramatic props in early mystery and science fiction motion pictures, starting in the silent era.[63] The crackling, writhing sparks emanating from the electrode of a giant Tesla coil became Hollywood's iconic symbol of the "mad scientist's" lab, recognized throughout the world.[143] This was probably because the eccentric Nikola Tesla himself, with his famous high voltage demonstrations and his mysterious Colorado Springs laboratory, was one of the main prototypes from which the "mad scientist" stock character originated.[143][144] Some early films in which Tesla coils appeared were Wolves of Kultur (1918), The Power God (1926), Metropolis (1927), Frankenstein (1931) and its many sequels such as Son of Frankenstein (1939), The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), Chandu the Magician (1932), The Lost City (1935), and The Clutching Hand (1936)[145][63] and many later films and television shows. By the 1980s, effects like high voltage sparks were being added to movies by CGI as visual effects in post-production, eliminating the need for dangerous high voltage Tesla coils on sets.

The Tesla coils for many of these movies were constructed by Kenneth Strickfaden (1896-1984) who, beginning with his spectacular effects in the 1931 Frankenstein, became Hollywood's preeminent electrical special effects expert.[63][146] His large "Meg Senior" Tesla coil seen in many of these movies consisted of a 6 foot 1000 turn conical secondary and a 10 turn primary, connected to a capacitor through a rotary spark gap, powered by a 20 kV transformer.[146] It could produce 6 foot sparks. Some of his last gigs were the reassembly of the original 1931 Frankenstein high voltage apparatus for the Mel Brooks satire Young Frankenstein (1974), and construction of a million volt Tesla coil which produced 12 foot sparks for a 1976 stage show by the rock band Kiss.[145]

Use in education

Ever since Tesla's 1890s lectures, Tesla coils have been used as attractions in educational exhibits and science fairs. They have become a way to counter the stereotype that science is boring.[148] In the early 20th century, experts like Henry Transtrom and Earle Ovington gave high voltage demonstrations at "electric fairs".[136] High school classes built Tesla coils.

From 1933 into the 1980s, between movie jobs Hollywood special effects expert Ken Strickfaden would take his high voltage apparatus on the road in an exhibition called "Science on Parade" and later "The Kenstric Space Age Science Show" to high schools, colleges, World Fairs and expositions.[148] These spectacular shows, which reached 48 states, had a seminal influence on the birth of the modern "coiling" movement.[145] A number of present-day Tesla hobbyists such as William Wysock say they were inspired to build Tesla coils by seeing Strickfaden's show.[148]

One of the oldest and best-known coils still in operation is the "GPO-1" at Griffith Park Observatory in Los Angeles. It was originally one of a pair of coils built in 1910 by Earle L. Ovington, a friend of Tesla and manufacturer of high voltage electrotherapy apparatus.[149][150][63] For a number of years Ovington displayed them at the December electrical trade show at Madison Square Garden in New York City, using them for demostrations of high voltage science, which Tesla himself sometimes attended.[150] Called the Million Volt Oscillator, the twin coils were installed on the balcony at the show. Every hour the lights were dimmed and the public was treated to a display of 10 foot arcs. Ovington gave the coils to his friend Dr. Frederick Finch Strong, a leading figure in the alternative health field of electrotherapy. In 1937 Strong donated the coils to the Griffith Observatory. The museum didn't have room to display both, but one coil was restored by Kenneth Strickfaden and has been in daily operation ever since.[63] It consists of a 48 in. (1.2 m) high conical secondary coil topped by a 12 in. (30 cm) diameter copper ball electrode, with a 9-turn spiral primary of 2 in. copper strip, a glass plate capacitor (replacing the original Leyden jars), and rotary spark gap.[149] Its output has been estimated at 1.3 million volts.[150]

Later uses

In addition to its use in spark-gap radio transmitters and electrotherapy described above, the Tesla coil circuit was also used in the early 20th century in x-ray machines, ozone generators for water purification, and induction heating equipment. However in the 1920s vacuum tube oscillators replaced it in all these applications.[9] The triode vacuum tube was a much better radio frequency current generator than the noisy, hot, ozone-producing spark, and could produce continuous waves. After this, industrial use of the Tesla coil was mainly limited to a few specialized applications which were suited to its unique characteristics, such as high voltage insulation testing.

In 1926, pioneering accelerator physicists Merle Tuve and Gregory Breit built a 5 million volt Tesla coil as a linear particle accelerator.[151][152][153] The bipolar coil consisted of a pyrex tube a meter long wound with 8000 turns of fine wire, with round corona caps on each end, and a 5 turn spiral primary coil surrounding it at the center. It was operated in a tank of insulating oil pressurized to 500 psi which allowed it to reach a potential of 5.2 megavolts. Although it was used for a short period in 1929-30 it was not a success because the particles' acceleration had to be completed within the brief period of a half cycle of the RF voltage.

In 1970 Robert K. Golka built a replica of Tesla's huge Colorado Springs magnifying transmitter in a shed at Wendover Air Force Base, Utah, using data he found in Tesla's lab notes archived at the Nikola Tesla Museum in Beograd, Serbia.[85][97] [98][33] This was one of the first experiments with the magnifier circuit since Tesla's time. The coil generated 12 million volts. Golka used it to try to duplicate Tesla's reported synthesis of ball lightning.

References

- ^ a b c d Uth, Robert (December 12, 2000). "Tesla coil". Tesla: Master of Lightning. PBS.org. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Dommermuth-Costa, Carol (1994). Nikola Tesla: A Spark of Genius. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 75. ISBN 0-8225-4920-4.

- ^ "Tesla coil". Museum of Electricity and Magnetism, Center for Learning. National High Magnetic Field Laboratory website, Florida State Univ. 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Instruction and Application Manual" (PDF). Model 10-206 Tesla Coil. Science First, Serrata, Pty. educational equipment website. 2006. p. 2. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Cheney, Margaret (2011). Tesla: Man Out of Time. Simon and Schuster. p. 87. ISBN 1-4516-7486-4.

- ^ Constable, George; Bob Somerville (2003). A Century of Innovation: Twenty Engineering Achievements that Transformed Our Lives. Joseph Henry Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-309-08908-5.

- ^ a b Smith, Craig B. (2008). Lightning: Fire from the Sky. Dockside Consultants Inc. ISBN 0-615-24869-1.

- ^ a b Plesch, P. H. (2005). High Vacuum Techniques for Chemical Syntheses and Measurements. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-521-67547-2.

- ^ a b c d e Tilbury, Mitch (2007). The Ultimate Tesla Coil Design and Construction Guide. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1. ISBN 0-07-149737-4.

- ^ Ramsey, Rolla (1937). Experimental Radio (4th ed.). New York: Ramsey Publishing. p. 175.

- ^ a b Mazzotto, Domenico (1906). Wireless telegraphy and telephony. Whittaker and Co. p. 146.

- ^ a b c Sarkar, T. K.; Mailloux, Robert; Oliner, Arthur A.; et al. (2006). History of Wireless. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 286, 84. ISBN 0-471-78301-3., archive

- ^ a b c d "Unfortunately, the common misunderstanding by most people today is that the Tesla coil is merely a device that produces a spectacular exhibit of sparks which tittilates audiences. Nevertheless, its circuitry is fundamental to all radio transmission" Belohlavek, Peter; Wagner, John W (2008). Innovation: The Lessons of Nikola Tesla. Blue Eagle Group. p. 110. ISBN 9876510096. Cite error: The named reference "Belohlavek" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Haddad, A.; Warne, D.F. (2004). Advances in High Voltage Engineering. IET. p. 605. ISBN 0852961588.

- ^ a b c d Naidu, M. S.; Kamaraju, V. (2013). High Voltage Engineering. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 167. ISBN 1259062899.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sprott, Julien C. (2006). Physics Demonstrations: A Sourcebook for Teachers of Physics. Univ. of Wisconsin Press. pp. 192–195. ISBN 0299215806.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anderson, Barton B. (November 24, 2000). "The Classic Tesla Coil: A dual-tuned resonant transformer" (PDF). Tesla Coils. Terry Blake. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Denicolai, Marco (May 30, 2001). "Tesla Transformer for Experimentation and Research" (PDF). Thesis for Licentiate Degree. Electrical and Communications Engineering Dept., Helsinki Univ. of Technology, Helsinki, Finland: 2–6. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e Denicolai, 2001, Tesla Transformer for Experimentation and Research, Ch.2, p. 8-10

- ^ a b c Gerekos, Christopher (2012). "The Tesla Coil" (PDF). Thesis. Physics Dept., Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium: 20–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help), reprinted on The Zeus Tesla Coil, HazardousPhysics.com - ^ Gottlieb, Irving (1998). Practical Transformer Handbook: for Electronics, Radio and Communications Engineers. Newnes. pp. 103–114. ISBN 0080514561.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Burnett, Richie (2008). "Operation of the Tesla Coil". Richie's Tesla Coil Web Page. Richard Burnett private website. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b Burnett, Richie (2008). "Tesla Coil Components, P. 2". Richie's Tesla Coil Web Page. Richard Burnett private website. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Gerekos, 2012, The Tesla Coil, p. 38-42 Archived June 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Gerekos, 2012, The Tesla Coil, p. 15-18 Archived June 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Cite error: The named reference "Gerekos2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Gerekos, 2012, The Tesla Coil, p. 19-20 Archived June 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tesla Coils - Frequently Asked Questions". oneTesla website. oneTesla Co., Cambridge, MA. 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Denicolai, 2001, Tesla Transformer for Experimentation and Research, Ch.2, p. 11-17

- ^ Gerekos, 2012, The Tesla Coil, p. 1, 23 Archived June 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Denicolai, 2001, Tesla Transformer for Experimentation and Research, Ch.2, p. 10

- ^ a b US Patent No. 1119732, Nikola Tesla Apparatus for transmitting electrical energy, filed January 18, 1902; granted December 1, 1914

- ^ a b c d e f Sarkar et al. (2006) History of Wireless, p. 279-280, archive

- ^ a b Reed, John Randolph (2000). "Designing high-gain triple resonant Tesla transformers" (PDF). Dept. of Engineering and Computer Science, Univ. of Central Florida. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Thomson, Elihu (November 3, 1899). "Apparatus for obtaining high frequencies and pressures". The Electrician. 44 (2). London: The Electrician Publishing Co.: 40–41. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Strong, Frederick Finch (1908). High Frequency Currents. New York: Rebman Co. pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Tesla, Nikola (March 29, 1899). "Some experiments in Tesla's laboratory with currents of high frequencies and pressures". Electrical Review. 34 (13). New York: Electrical Review Publishing Co.: 193–197. Retrieved November 30, 2015. p. 196-197 and fig. 2: Tesla describes the steps in his invention of the high frequency transformer.

- ^ a b c Denicolai, 2001, Tesla Transformer for Experimentation and Research, Ch.1, p. 1-6

- ^ a b US Patent No. 454622, Nikola Tesla System of electric lighting, filed April 25, 1891; granted June 23, 1891

- ^ a b c The lecture "Experiments with Alternate Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination" is reprinted in Martin, Thomas Cummerford (1894). The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla: With Special Reference to His Work in Polyphase Currents and High Potential Lighting, 2nd Ed. The Electrical Engineer. pp. 145–197. The Tesla coil circuit is shown p. 193, fig. 127

- ^ The lecture is reprinted in Tesla, Nikola (2007). The Nikola Tesla Treasury. Wilder Publications. pp. 68–107. ISBN 1934451894. The Tesla coil illustration is shown p. 103, fig. 32

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sarkar, T. K.; Mailloux, Robert; Oliner, Arthur A.; et al. (2006). History of Wireless. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 268–270. ISBN 0471783013.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first3=(help), archive - ^ a b Thomson, Elihu (February 20, 1892). "Induction by high potential discharges". Electrical World. 19 (8). New York: W. J. Johnson Co.: 116–117. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Aitken, Hugh G.J. (2014). Syntony and Spark: The Origins of Radio. Princeton Univ. Press. pp. 23–25, 31–36. ISBN 1400857880.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton University Press. pp. 119–125. ISBN 1400846552. Cite error: The named reference "Carlson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Uth, Robert (1999). Tesla, Master of Lightning. Barnes and Noble Publishing. pp. 65–70. ISBN 0760710058.

- ^ a b c d "Tesla is entitled to either distinct priority or independent discovery of" three concepts in wireless theory: "(1) the idea of inductive coupling between the driving and the working circuits (2) the importance of tuning both circuits, i.e. the idea of an 'oscillation transformer' (3) the idea of a capacitance loaded open secondary circuit" Wheeler, L. P. (August 1943). "Tesla's contribution to high frequency". Electrical Engineering. 62 (8). IEEE: 355–357. doi:10.1109/EE.1943.6435874. ISSN 0095-9197.

- ^ a b c d e Pierce, George Washington (1910). Principles of Wireless Telegraphy. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b c d e Fleming, John Ambrose (1910). The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy and Telephony, 2nd Ed. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 581–582.

- ^ a b "Tesla's system of electric power transmission through natural media". The Electrical Review. 43 (1094). New York: H. Alabaster, Gatehouse and Co.: 709 November 11, 1898. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ Tesla stated in Nikola Tesla My Inventions - Ch. 5: The Magnifying Transmitter, Electrical Experimenter, Vol. 7, No. 2, June 1919, p. 112, that this picture showed a prototype of his magnifying transmitter, a smaller version of the apparatus installed in his Colorado Springs lab.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (July 1919). "Electrical Oscillators" (PDF). Electrical Experimenter. 7 (3). New York: Experimenter Publishing Co.: 228–229, 259–260. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Transformer". Encyclopaedia Britannica, 10th Ed. Vol. 33. The Encyclopaedia Britannica Co. 1903. p. 426. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Thomson, Elihu (April, 1893). "High Frequency Electric Induction". Technology Quarterly and Proceedings of Society of Arts. 6 (1). Boston: Massachussets Inst. of Technology: 50–59. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Thomson, Elihu (July 23, 1906). "Letter to Frederick Finch Strong". The Electrotherapy Museum website. Jeff Behary, Bellingham, Washington, USA. Reproduced by permission of The American Philosophical Society. Retrieved August 20, 2015. In this letter Thomson lists papers he published in technical journals which support his claim to priority in inventing the "Tesla coil" resonant transformer circuit

- ^ Fessenden, Reginald A. (August 1908). "Wireless Telephony". Telephony. 16 (2). Chicago, Illinois: The Telephony Publishing Co.: 75. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ "The length of the...coil in each transformer should be approximately one quarter of the wave length of the electric disturbance in the circuit, this estimate being based on the velocity of propagation of the disturbaiice through the coil itself..." US Patent No. 645576, Nikola Tesla, System of transmission of electrical energy, filed September 2, 1897; granted March 20, 1900

- ^ Oberbeck, A. (1895). "Ueber den Verlauf der electrischen Schwingungen bei den Tesla'schen Versuchen (On the electrical oscillations in Tesla's experiments)". Annalen der Physik. 291 (8). Berlin: Wiedemann: 623–632. doi:10.1002/andp.18952910808. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Drude, P. (February 1904). "Über induktive Erregung zweier elektrischer Schwingungskreise mit Anwendung auf Periodenund Dämpfungsmessung, Teslatransformatoren und drahtlose Telegraphie (Of inductive excitation of two electric resonant circuits with application to measure-ment of oscillation periods and damping, Tesla coils, and wireless telegraphy)". Annalen der Physik. 13 (3). Wiley-VCH: 512–561. doi:10.1002/andp.18943180306.. ISSN 1521-3889. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help), English translation - ^ a b c d W. Bernard Carlson 2013 Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, p. 133-137 Cite error: The named reference "Carlson2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ A description of this demonstration which Tesla organized at the Westinghouse exhibit at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in St. Louis is found in Barrett, John Patrick (1894). Electricity at the Columbian Exposition; Including an Account of the Exhibits in the Electricity Building, the Power Plant in Machinery Hall. pp. 168–169. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ Thomas Cummerford Martin 1894 The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla, 2nd Ed., p. 198-293

- ^ a b "On light and other high frequency phenomena", Thomas Cummerford Martin 1894 The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla, 2nd Ed., p. 294-373

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goldman, Harry (2005). Kenneth Strickfaden, Dr. Frankenstein's Electrician. McFarland. pp. 77–83. ISBN 0786420642.

- ^ a b c d Sterling, Christopher H. (2013). Biographical Encyclopedia of American Radio. Routledge. pp. 382–383. ISBN 1136993754.

- ^ a b c d US Patent No. 645576, Nikola Tesla, System of transmission of electrical energy, filed September 2, 1897; granted March 20, 1900

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lee, Thomas H. (2004). The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits. Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 0521835399.

- ^ a b c Curty, Jari-Pascal; Declercq, Michel; Dehollain, Catherine; Joehl, Norbert (2006). Design and Optimization of Passive UHF RFID Systems. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 0387447105.

- ^ a b c d e f Shinohara, Naoki (2014). Wireless Power Transfer via Radiowaves. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 1118862961.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lee, C.K.; Zhong, W.X.; Hui, S.Y.R. (September 5, 2012). Recent Progress in Mid-Range Wireless Power Transfer (PDF). The 4th Annual IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE 2012). Raleigh, North Carolina: Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers. pp. 3819–3821. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Tesla, Nikola (May 20, 1891) Experiments with Alternate Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination, lecture before the American Inst. of Electrical Engineers, Columbia College, New York. Reprinted as a book of the same name by. Wildside Press. 2006. ISBN 0809501627.

- ^ Tesla was notoriously secretive about the distance he could transmit power. One of his few disclosures of details was in the caption of fig. 7 of his noted magazine article: The Problem of Increasing Human Energy, Century magazine, June 1900. The caption reads: "EXPERIMENT TO ILLUSTRATE AN INDUCTIVE EFFECT OF AN ELECTRICAL OSCILLATOR OF GREAT POWER - The photograph shows three ordinary incandescent lamps lighted to full candle-power by currents induced in a local loop consisting of a single wire forming a square of fifty feet each side, which includes the lamps, and which is at a distance of one hundred feet from the primary circuit energized by the oscillator. The loop likewise includes an electrical condenser, and is exactly attuned to the vibrations of the oscillator, which is worked at less than five percent of its total capacity."

- ^ Leyh, G. E.; Kennan, M. D. (September 28, 2008). Efficient wireless transmission of power using resonators with coupled electric fields (PDF). NAPS 2008 40th North American Power Symposium, Calgary, September 28–30, 2008. Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1109/NAPS.2008.5307364. ISBN 978-1-4244-4283-6. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Sazonov, Edward; Neuman, Michael R (2014). Wearable Sensors: Fundamentals, Implementation and Applications. Elsevier. pp. 253–255. ISBN 0124186661.

- ^ Agbinya, Johnson I. (February 2013). "Investigation of near field inductive communication system models, channels, and experiments" (PDF). Progress In Electromagnetics Research B. 49. EMW Publishing: 130. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Bolic, Miodrag; Simplot-Ryl, David; Stojmenovic, Ivan (2010). RFID Systems: Research Trends and Challenges. John Wiley & Sons. p. 29. ISBN 0470975660.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (June 1900). "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy". Century Magazine. New York: The Century Co. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c Tesla, Nikola (March 5, 1904). "The Transmission of Electric Energy Without Wires". Electrical World and Engineer. 43. McGraw Publishing Co.: 23760–23761. Retrieved November 19, 2014., reprinted in Scientific American Supplement, Munn and Co., Vol. 57, No. 1483, June 4, 1904, p. 23760-23761

- ^ a b c d Broad, William J. (May 4, 2009). "A Battle to Preserve a Visionary's Bold Failure". New York Times. New York: The New York Times Co. pp. D1. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ Carlson 2013 Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, p. 209-210

- ^ a b c Cheney, Margaret (2011) Tesla: Man Out of Time, p. 187-189

- ^ a b Sewall, Charles Henry (1903). Wireless telegraphy: its origins, development, inventions, and apparatus. D. Van Nostrand Co. pp. 38–42.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (March 8, 1907). "Tuned Lightning". English Mechanic and World of Science. Retrieved October 18, 2015., reprinted in Tesla, Nikola (2012). The Nikola Tesla Treasury. Start Publications LLC. p. 526. ISBN 1627932569.

- ^ a b c Tesla, Nikola (June 1919). "My Inventions V. - The Magnifying Transmitter" (PDF). Electrical Experimenter. 7 (2). New York: Experimenter Publishing Co.: 112. Retrieved August 8, 2015., reprinted in Nikola Tesla, My Inventions, The Philovox, 1919, Ch. 5 republished as Tesla, Nikola (2007). My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla. Wilder Publications. pp. 53–16. ISBN 1934451770.

- ^ a b Martin, James M. (1912). Practical electro-therapeutics and X-ray therapy. C.V. Mosby Co. pp. 187–192.

- ^ a b c Shunamen, Fred (June 1976). "12 Million Volts" (PDF). Radio-Electronics. 47 (6). Gernsback Publications, Inc.: 32–34, 69. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Mitchell, Donald P. (1972). "Nikola Tesla's Investigation of High Frequency Phenomena and Radio Communication, Part 2". Don P. Mitchell Homepage. Mental Landscape LLC. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Sarkar, T. K.; Mailloux, Robert; Oliner, Arthur A.; et al. (2006). History of Wireless. John Wiley and Sons. p. 283. ISBN 0471783013.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first3=(help), archive - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Coe, Lewis (2006). Wireless Radio: A History. McFarland. pp. 111–113. ISBN 0786426624.

- ^ Hawkins, Lawrence A. (February 1903). "Nikola Tesla: His Work and Unfulfilled Promises". The Electrical Age. 30 (2): 107–108. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Cheney, Margaret; Uth, Robert; Glenn, Jim (1999). Tesla, Master of Lightning. Barnes & Noble Publishing. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0760710058.

- ^ a b c d Tomar, Anuradha; Gupta, Sunil (July 2012). "Wireless Power Transmission: Applications and Components". International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology. 1 (5). ISSN 2278-0181. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Brown, William C. (1984). "The history of power transmission by radio waves". MTT-Trans. on Microwave Theory and Technique. 32 (9). Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers: 1230–1234. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "Life and Legacy: Colorado Springs". Tesla: Master of Lightning - companion site for 2000 PBS television documentary. PBS.org, Public Broadcasting Service website. 2000. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Cooper, Christopher (2015). The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation. Race Point Publishing. pp. 171–172. ISBN 1631060309.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (1977). Marinčić, Aleksandar (ed.). Colorado Springs Notes, 1899-1900. Beograd, Yugoslavia: The Nikola Tesla Museum.

- ^ O'Neill, John J. (1944). Prodigal Genius: The life of Nikola Tesla. Ives Washburn, Inc. p. 193.

- ^ a b Golka, Robert K. (February 1981). "Project Tesla - In Search of an Answer to Our Energy Needs". Radio-Electronics. 52 (2). New York: Gernsback Publications, Inc.: 47–49. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Lawren, Bill (March 1988). "Rediscovering Tesla". Omni Magazine. 10 (6): 64–66, 68, 116–117. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ For example, using Tesla coils Leyh and Kennan only achieved 1.5% power throughput at a distance of 30 meters, only 5 times the transmitter diameter. Leyh, G. E.; Kennan, M. D. (September 28, 2008). Efficient wireless transmission of power using resonators with coupled electric fields (PDF). NAPS 2008 40th North American Power Symposium, Calgary, September 28–30, 2008. Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1109/NAPS.2008.5307364. ISBN 978-1-4244-4283-6. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "Dennis Papadopoulos interview". Tesla: Master of Lightning - companion site for 2000 PBS television documentary. PBS.org, Public Broadcasting Service website. 2000. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c US Patent no. 763,772, Guglielmo Marconi, Apparatus for wireless telegraphy, filed: November 10, 1900, granted: June 28, 1904. Corresponding British patent no. 7777, Guglielmo Marconi, Improvements in apparatus for wireless telegraphy, filed: April 26, 1900, granted: April 13, 1901

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rockman, Howard B. (2004). Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 196–199. ISBN 0471697397.

- ^ Eccles, William H. (1933). Wireless. T. Butterworth, Ltd. p. 80. quoted in Sarkar, Mailloux, Oliner (2006) History of Wireless, p. 268. Eccles was a contemporary of Tesla

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sarkar et al (2006) History of Wireless, p. 352-353, 355-357, archive

- ^ a b Aitken, Hugh 2014 Syntony and Spark: The origins of radio, p. 70-73

- ^ Crookes, William (February 1, 1892). "Some Possibilities of Electricity". The Fortnightly Review. 51. London: Chapman and Hall: 174–176. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Aitken, Hugh 2014 Syntony and Spark: The origins of radio, p. 254-255, 259

- ^ a b c d e f g h Klooster, John W. (2007). Icons of Invention. ABC-CLIO. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0313347433.

- ^ a b c Cheney, Margaret (2011) Tesla: Man Out Of Time, p. 96-97

- ^ a b Regal, Brian (2005). Radio: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0313331677.

- ^ a b The "four circuit" radio system, which Marconi claimed in his 1900 patent, meant a transmitter and receiver which each contained a resonant transformer and thus were divided into primary and secondary circuits. All four circuits were tuned to the same frequency, one side by capacitors, and the other side by the capacitance of the antenna; "the use of two high frequency circuits in the transmitter and two in the receiver, all four so adjusted to be resonant at the same frequency or multiples of it." "No. 369 (1943) Marconi Wireless Co. of America v. United States". United States Supreme Court decision. Findlaw.com website. June 21, 1943. Retrieved March 14, 2017. This was identical to the system Tesla demonstrated in 1893. The advantage of this system was that due to the resonant transformers both the receiver and transmitter had much narrower bandwidth than previous circuits.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (May 1919). "The True Wireless" (PDF). Electrical Experimenter. 7 (1). New York: Experimenter Publishing Co.: 28–30, 61. Retrieved February 20, 2017. archived on tfcbooks

- ^ US Patent no. 714,756, John Stone Stone Method of electric signaling, filed: February 8, 1900, granted: December 2, 1902

- ^ US Patent no. 609,154 Oliver Joseph Lodge, Electric Telegraphy, filed: February 1, 1898, granted: August 16, 1898

- ^ "No. 369 (1943) Marconi Wireless Co. of America v. United States". United States Supreme Court decision. Findlaw.com website. June 21, 1943. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ White, Thomas H. (November 1, 2012). "Nikola Tesla: The Guy Who DIDN'T "Invent Radio"". United States Early Radio History. T. H. White's personal website. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ Manders, Horace (August 1, 1902). "Some phenomena of high frequency currents". Journal of Physical Therapeutics. 3 (1). London: John Bale, Sons, and Danielsson, Ltd.: 220–221. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ McGinley, Patton H. "Tesla's contributions to electrotherapy" in Childress, David Hatcher, Ed. (2000). The Tesla Papers. Adventures Unlimited Press. pp. 162–167. ISBN 0932813860.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tesla, Nikola (November 17, 1898). "High frequency oscillators for electro-therapeutic and other purposes". The Electrical Engineer. 26 (550): 477–481. Retrieved June 10, 2015. Also read at the 8th annual meeting of The American Electro-Therapeutic Association, Buffalo, New York, Sept. 13-15, 1898

- ^ a b c Rhees, David J. (July 1999). "Electricity - "The greatest of all doctors": An introduction to "High Frequency Oscillators for Electro-therapeutic and Other Purposes"" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 87 (7). Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers: 1277–1281. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Kovács, Richard (1945). Electrotherapy and Light Therapy, 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger. pp. 187–188, 197–200.

- ^ a b Cheney (2011) Tesla:Man Out of Time, p. 103

- ^ Gilliams, E. Leslie (December 1912). "Tesla's Plan Of Electrically Treating School Children". Popular Electricity. New York: The Popular Electricity Publishing Co.: 813–814. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ he also wrote a second earlier medical paper: Tesla, N. "High frequency currents for medical purposes" in Electrical Engineer, 1891, cited in Saberton, Claude (1920) Diathermy in Medical and Surgical Practice, published by Paul B. Hoeber, New York, p. 131

- ^ a b Morton, W. J. (January 17, 1893). "A brief glance at electricity in medicine". Transactions of the American Inst. of Electrical Engineers. New York: AIEE: 576–578. Retrieved September 21, 2015. Cite error: The named reference "Morton" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Batten, George B. (October 15, 1926). "President's Address" (PDF). Proc. of the Royal Society of Medicine - Electro-therapeutics section. 20 (1). London: 33–34. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Chisolm (1903). High Frequency Currents in the Treatment of Some Diseases. London: Rebman, Ltd. pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e Ho, Mae-Wan; Popp, Fritz Albert; Warnke, Ulrich (1994). Bioelectrodynamics and Biocommunication. World Scientific. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9810216653.

- ^ D'Arsonval, A. (August 1893). "Physiological action of currents of great frequency". Modern Medicine and Bacteriological World. 2 (8). Modern Medicine Publishing Co.: 200–203. Retrieved November 22, 2015., translated by J. H. Kellogg

- ^ Martin, James M. (1912). Practical electro-therapeutics and X-ray therapy. C.V. Mosby Co., p.189 fig. 98

- ^ a b c De la Peña, Carolyn Thomas (2005). The Body Electric: How Strange Machines Built the Modern American. NYU Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 081471983X.

- ^ a b Behary, Jeff (1997). "Violet Ray Misconceptions". The Electrotherapy Museum. Jeff Behary's website. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ The small high voltage coils in these home violet ray wands resembled induction coils more than Tesla coils; they had iron core transformers and mechanical interrupters and produced lower voltages than Tesla coils

- ^ Behary, Jeff (Sun, 1 July 2007 06:56:03 -0600 (MDT)). "RE: Oudin coil". Tesla Coil Mailing List (Mailing list). Retrieved 16 November 2015.

{{cite mailing list}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "Electrice" (1914). "Doing and Daring for the Public's Pleasure". Popular Electricity. 6 (9). Chicago: Popular Electricity Publishing Co.: 1044–1046. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Many of these stunts are demonstrated and explained in Transtrom, Henry L. (1913). Electricity at high pressures and frequencies. Joseph G. Branch Publishing Co. pp. 189–207.

- ^ "Madamoiselle Electra" (October 1911). "How I Give the Public Electric Thrills". Popular Electricity. 4 (6). Chicago: Popular Electricity Publishing Co.: 507–510. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c Gangi, Tony (2010). Carny Sideshows. Kensington Publishing. p. 206. ISBN 0806535989.

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe (2005). Secrets of the Sideshows. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 248–249. ISBN 0813137373.