Vine-Glo: Difference between revisions

The C of E (talk | contribs) |

Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

== Cessation == |

== Cessation == |

||

When Vine-Glo first came out, the pro-prohibitionists protested it but the [[United States Assistant Attorney General|Assistant Attorney General]] [[Mabel Walker Willebrandt]] ruled that it was legal under the Volstead Act and the [[Bureau of Prohibition]] told its agents not to interfere with shipments.<ref name=t /><ref>{{cite book |first=Richard |last=Mendelson |title=From Demon to Darling: A legal history of wine in America |page=74 |year=2010 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0520268005}}</ref> By 1931, Fruit Industries were having to produce adverts asserting that Vine-Glo did not break any laws following constant criticism from dry communities.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Look+back+to+the+future-a076473189 |title=Look back to the future. |via=Free Online Library |publisher=Wine & Vine |date=2001-04-01 |access-date=2020-12-20}}</ref> When Willebrandt stepped down from the government she became an attorney for Fruit Industries. This conflict of interest caused embarrassment to the government who started to treat Vine-Glo with a more hostile manner.<ref name=g /> Though Fruit Industries got another $1,000,000 loan from the Farm Board in October 1931, in the same month a federal judge ruled in ''United States v Brunett'' that grape concentrate could not be legally used to make fruit juice. Fruit Industries ceased making Vine-Glo a month later after the court decision was affirmed by the Director of the Bureau of Prohibition who said they would not allow grape concentrate to be exempt under section 29.<ref name=t /> |

When Vine-Glo first came out, the pro-prohibitionists protested it but the [[United States Assistant Attorney General|Assistant Attorney General]] [[Mabel Walker Willebrandt]] ruled that it was legal under the Volstead Act and the [[Bureau of Prohibition]] told its agents not to interfere with shipments.<ref name=t /><ref>{{cite book |first=Richard |last=Mendelson |title=From Demon to Darling: A legal history of wine in America |page=74 |year=2010 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0520268005}}</ref> By 1931, Fruit Industries were having to produce adverts asserting that Vine-Glo did not break any laws following constant criticism from dry communities.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Look+back+to+the+future-a076473189 |title=Look back to the future. |via=Free Online Library |publisher=Wine & Vine |date=2001-04-01 |access-date=2020-12-20}}</ref>{{explain|“dry communities”? Those in deserts, those who didn’t drink alcohol, or aquaphobes? Perhaps rephrasing or a link somewhere would be helpful}} When Willebrandt stepped down from the government she became an attorney for Fruit Industries. This conflict of interest caused embarrassment to the government who started to treat Vine-Glo with a more hostile manner.<ref name=g /> Though Fruit Industries got another $1,000,000 loan from the Farm Board in October 1931, in the same month a federal judge ruled in ''United States v Brunett'' that grape concentrate could not be legally used to make fruit juice. Fruit Industries ceased making Vine-Glo a month later after the court decision was affirmed by the Director of the Bureau of Prohibition who said they would not allow grape concentrate to be exempt under section 29.<ref name=t /> |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 17:28, 17 January 2021

| |

| Type | Grape concentrate |

|---|---|

| Inventor | Joseph Gallo |

| Inception | 1929 |

| Manufacturer | Fruit Industries |

| Available | Not available |

| Last production year | 1931 |

Vine-Glo was a grape concentrate brick product sold in the United States during Prohibition by Fruit Industries Ltd, a front for the California Vineyardist Association (CVA), from 1929. It was sold as a grape concentrate to make grape juice from but it included a specific warning that told people how to make wine from it.[1] Fruit Industries ceased producing it in 1931 following a federal court ruling that making wine from concentrate violated section 29 of the Volstead Act.[2]

History

When Prohibition banned alcohol in the United States under the Volstead Act, it produced a number of loopholes. One under section 29 said that non-alcoholic grape products could still be sold and people could make fruit juices at home from them. The CVA founded Fruit Industries and received a $1,300,000 loan from the Federal Farm Board.[3] Dr Joseph Gallo invented Vine-Glo as a legal grape concentrate brick and would sell it through Fruit Industries.[4] On the packaging, it included a very specific warning: "After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not place the liquid in a jug away in the cupboard for twenty days, because then it would turn into wine."[1] Fruit Industries also promoted the Farm Board and carried a statement it was "legal in your own home".[2]

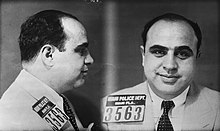

When the product went on sale, 1 million gallons of Vine-Glo were sold with eight wine-flavored varieties created in the first financial year.[1] The product was sold across the United States. Reportedly when Fruit Industries tried to launch the product in Chicago in 1930, Al Capone allegedly threatened to force them out of Chicago but Fruit Industries responded by publishing a statement saying they would not be intimidated and would push on.[2][5] However, it has been speculated that this was just a promotional tactic.[2] The product eventually went on sale in New York State in 1931.[6]

Cessation

When Vine-Glo first came out, the pro-prohibitionists protested it but the Assistant Attorney General Mabel Walker Willebrandt ruled that it was legal under the Volstead Act and the Bureau of Prohibition told its agents not to interfere with shipments.[2][7] By 1931, Fruit Industries were having to produce adverts asserting that Vine-Glo did not break any laws following constant criticism from dry communities.[8][further explanation needed] When Willebrandt stepped down from the government she became an attorney for Fruit Industries. This conflict of interest caused embarrassment to the government who started to treat Vine-Glo with a more hostile manner.[1] Though Fruit Industries got another $1,000,000 loan from the Farm Board in October 1931, in the same month a federal judge ruled in United States v Brunett that grape concentrate could not be legally used to make fruit juice. Fruit Industries ceased making Vine-Glo a month later after the court decision was affirmed by the Director of the Bureau of Prohibition who said they would not allow grape concentrate to be exempt under section 29.[2]

References

- ^ a b c d Hines, Nicholas (2015-09-17). "Prohibition's Grape Bricks: How not to make wine". Grape Collective. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ a b c d e f Pinney, Thomas (2005). A History of Wine in America. Vol. 2. University of California Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0520241762.

- ^ "BEER, WINE APPROVAL FORECAST". Healdsburg Tribune. 1930-11-12. Retrieved 2020-12-20 – via University of California.

- ^ "Great dynasties of the world: The Gallos". The Guardian. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Grape Growers defy reported Capone threat". Chicago Tribune. 1930-11-14. Retrieved 2020-12-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Now New York homes can enjoy Vine-Glo". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1931-03-03. Retrieved 2020-12-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mendelson, Richard (2010). From Demon to Darling: A legal history of wine in America. University of California Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0520268005.

- ^ "Look back to the future". Wine & Vine. 2001-04-01. Retrieved 2020-12-20 – via Free Online Library.