Saddle point: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

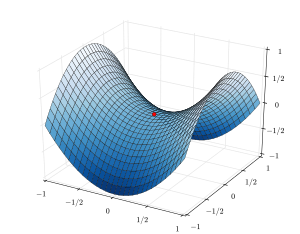

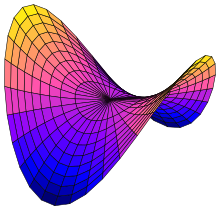

In [[mathematics]], a '''saddle point''' or '''minimax point'''<ref>Howard Anton, Irl Bivens, Stephen Davis (2002): ''Calculus, Multivariable Version'', p. 844.</ref> is a [[Point (geometry)|point]] on the [[surface (mathematics)|surface]] of the [[graph of a function]] where the [[slope]]s (derivatives) in orthogonal directions are all zero (a [[Critical point (mathematics)|critical point]]), but which is not a [[local extremum]] of the function.<ref>{{cite book |last = Chiang |first = Alpha C. |title = Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics |url = https://archive.org/details/fundamentalmetho0000chia_h4v2 |url-access = registration |location=New York |publisher = [[McGraw-Hill]] |edition=3rd |year=1984 |isbn = 0-07-010813-7 |page = [https://archive.org/details/fundamentalmetho0000chia_h4v2/page/312 312] }}</ref> An example of a saddle point is when there is a critical point with a relative [[minimum]] along one axial direction (between peaks) and at a [[maxima and minima|relative maximum]] along the crossing axis. However, a saddle point need not be in this form. For example, the function <math>f(x,y) = x^2 + y^3</math> has a critical point at <math>(0, 0)</math> that is a saddle point since it is neither a relative maximum nor relative minimum, but it does not have a relative maximum or relative minimum in the <math>y</math>-direction. |

In [[mathematics]], a '''saddle point''' or '''minimax point'''<ref>Howard Anton, Irl Bivens, Stephen Davis (2002): ''Calculus, Multivariable Version'', p. 844.</ref> is a [[Point (geometry)|point]] on the [[surface (mathematics)|surface]] of the [[graph of a function]] where the [[slope]]s (derivatives) in orthogonal directions are all zero (a [[Critical point (mathematics)|critical point]]), but which is not a [[local extremum]] of the function.<ref>{{cite book |last = Chiang |first = Alpha C. |title = Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics |url = https://archive.org/details/fundamentalmetho0000chia_h4v2 |url-access = registration |location=New York |publisher = [[McGraw-Hill]] |edition=3rd |year=1984 |isbn = 0-07-010813-7 |page = [https://archive.org/details/fundamentalmetho0000chia_h4v2/page/312 312] }}</ref> An example of a saddle point is when there is a critical point with a relative [[minimum]] along one axial direction (between peaks) and at a [[maxima and minima|relative maximum]] along the crossing axis. However, a saddle point need not be in this form. For example, the function <math>f(x,y) = x^2 + y^3</math> has a critical point at <math>(0, 0)</math> that is a saddle point since it is neither a relative maximum nor relative minimum, but it does not have a relative maximum or relative minimum in the <math>y</math>-direction. |

||

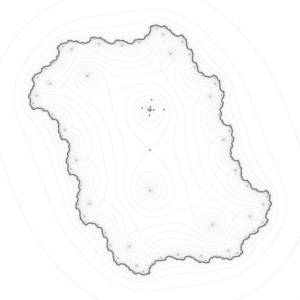

The name derives from the fact that the prototypical example in two dimensions is a [[surface (mathematics)|surface]] that ''curves up'' in one direction, and ''curves down'' in a different direction, resembling a riding [[saddle]] or a [[mountain pass]] between two peaks forming a [[Saddle (landform)|landform saddle]]. In terms of [[contour line]]s, a saddle point in two dimensions gives rise to a contour map ( graph or trace) with a pair of lines intersecting at the point. However typical ordnance survey maps for example don’t generally show such intersections as there is no reason such critical points in nature will just happen to coincide with typical integer multiple contour spacing. Instead dead space with 4 sets of contour lines approaching and veering away surround a basic saddle point with opposing high pair and opposing low pair in orthogonal directions. |

The name derives from the fact that the prototypical example in two dimensions is a [[surface (mathematics)|surface]] that ''curves up'' in one direction, and ''curves down'' in a different direction, resembling a riding [[saddle]] or a [[mountain pass]] between two peaks forming a [[Saddle (landform)|landform saddle]]. In terms of [[contour line]]s, a saddle point in two dimensions gives rise to a contour map ( graph or trace) with a pair of lines intersecting at the point. However typical ordnance survey maps for example don’t generally show such intersections as there is no reason such critical points in nature will just happen to coincide with typical integer multiple contour spacing. Instead dead space with 4 sets of contour lines approaching and veering away surround a basic saddle point with opposing high pair and opposing low pair in orthogonal directions. The critical contour lines generally don’t intersect perpendicularly. |

||

[[File:Julia set for z^2+0.7i*z.png|thumb|right|300px|Saddle point on the countour plot is the point where level curves cross ]] |

[[File:Julia set for z^2+0.7i*z.png|thumb|right|300px|Saddle point on the countour plot is the point where level curves cross ]] |

||

Revision as of 19:48, 3 April 2022

In mathematics, a saddle point or minimax point[1] is a point on the surface of the graph of a function where the slopes (derivatives) in orthogonal directions are all zero (a critical point), but which is not a local extremum of the function.[2] An example of a saddle point is when there is a critical point with a relative minimum along one axial direction (between peaks) and at a relative maximum along the crossing axis. However, a saddle point need not be in this form. For example, the function has a critical point at that is a saddle point since it is neither a relative maximum nor relative minimum, but it does not have a relative maximum or relative minimum in the -direction.

The name derives from the fact that the prototypical example in two dimensions is a surface that curves up in one direction, and curves down in a different direction, resembling a riding saddle or a mountain pass between two peaks forming a landform saddle. In terms of contour lines, a saddle point in two dimensions gives rise to a contour map ( graph or trace) with a pair of lines intersecting at the point. However typical ordnance survey maps for example don’t generally show such intersections as there is no reason such critical points in nature will just happen to coincide with typical integer multiple contour spacing. Instead dead space with 4 sets of contour lines approaching and veering away surround a basic saddle point with opposing high pair and opposing low pair in orthogonal directions. The critical contour lines generally don’t intersect perpendicularly.

Mathematical discussion

A simple criterion for checking if a given stationary point of a real-valued function F(x,y) of two real variables is a saddle point is to compute the function's Hessian matrix at that point: if the Hessian is indefinite, then that point is a saddle point. For example, the Hessian matrix of the function at the stationary point is the matrix

which is indefinite. Therefore, this point is a saddle point. This criterion gives only a sufficient condition. For example, the point is a saddle point for the function but the Hessian matrix of this function at the origin is the null matrix, which is not indefinite.

In the most general terms, a saddle point for a smooth function (whose graph is a curve, surface or hypersurface) is a stationary point such that the curve/surface/etc. in the neighborhood of that point is not entirely on any side of the tangent space at that point.

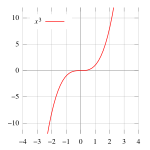

In a domain of one dimension, a saddle point is a point which is both a stationary point and a point of inflection. Since it is a point of inflection, it is not a local extremum.

Saddle surface

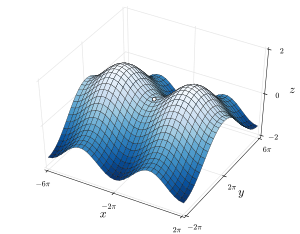

A saddle surface is a smooth surface containing one or more saddle points.

Classical examples of two-dimensional saddle surfaces in the Euclidean space are second order surfaces, the hyperbolic paraboloid (which is often referred to as "the saddle surface" or "the standard saddle surface") and the hyperboloid of one sheet. The Pringles potato chip or crisp is an everyday example of a hyperbolic paraboloid shape.

Saddle surfaces have negative Gaussian curvature which distinguish them from convex/elliptical surfaces which have positive Gaussian curvature. A classical third-order saddle surface is the monkey saddle.[3]

Examples

In a two-player zero sum game defined on a continuous space, the equilibrium point is a saddle point.

For a second-order linear autonomous system, a critical point is a saddle point if the characteristic equation has one positive and one negative real eigenvalue.[4]

In optimization subject to equality constraints, the first-order conditions describe a saddle point of the Lagrangian.

Other uses

In dynamical systems, if the dynamic is given by a differentiable map f then a point is hyperbolic if and only if the differential of ƒ n (where n is the period of the point) has no eigenvalue on the (complex) unit circle when computed at the point. Then a saddle point is a hyperbolic periodic point whose stable and unstable manifolds have a dimension that is not zero.

A saddle point of a matrix is an element which is both the largest element in its column and the smallest element in its row.

See also

- Saddle-point method is an extension of Laplace's method for approximating integrals

- Extremum

- Derivative test

- Hyperbolic equilibrium point

- Minimax theorem

- Max–min inequality

- Monkey saddle

- Mountain pass theorem

References

Citations

- ^ Howard Anton, Irl Bivens, Stephen Davis (2002): Calculus, Multivariable Version, p. 844.

- ^ Chiang, Alpha C. (1984). Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 312. ISBN 0-07-010813-7.

- ^ Buck, R. Creighton (2003). Advanced Calculus (3rd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. p. 160. ISBN 1-57766-302-0.

- ^ von Petersdorff 2006

Sources

- Gray, Lawrence F.; Flanigan, Francis J.; Kazdan, Jerry L.; Frank, David H.; Fristedt, Bert (1990), Calculus two: linear and nonlinear functions, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, p. 375, ISBN 0-387-97388-5

- Hilbert, David; Cohn-Vossen, Stephan (1952), Geometry and the Imagination (2nd ed.), New York, NY: Chelsea, ISBN 978-0-8284-1087-8

- von Petersdorff, Tobias (2006), "Critical Points of Autonomous Systems", Differential Equations for Scientists and Engineers (Math 246 lecture notes)

- Widder, D. V. (1989), Advanced calculus, New York, NY: Dover Publications, p. 128, ISBN 0-486-66103-2

- Agarwal, A., Study on the Nash Equilibrium (Lecture Notes)

Further reading

- Hilbert, David; Cohn-Vossen, Stephan (1952). Geometry and the Imagination (2nd ed.). Chelsea. ISBN 0-8284-1087-9.

External links

Media related to Saddle point at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Saddle point at Wikimedia Commons