Brazilian Romantic painting: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Pedro_Américo_-_D._Pedro_II_na_abertura_da_Assembléia_Geral.jpg|thumb|395x395px|Pedro Américo: ''The Emperor's |

[[File:Pedro_Américo_-_D._Pedro_II_na_abertura_da_Assembléia_Geral.jpg|thumb|395x395px|Pedro Américo: ''The Emperor's Speech'', 1872. [[Imperial Museum of Brazil]].]] |

||

'''Brazilian Romantic painting''' was the leading artistic expression in Brazil during the latter half of the 19th century, coinciding with the [[Second reign (Empire of Brazil)|Second Reign]]. It represented a unique evolution of the [[Romantic movement]]; it diverged significantly from its European counterpart and even the parallel Romantic movement in [[Brazilian literature]]. Characterized by a palatial and restrained aesthetic, it incorporated a strong [[Neoclassicism|neoclassical]] influence and gradually integrated elements of [[Realism (arts)|Realism]], [[Symbolism (arts)|Symbolism]], and other schools, resulting in an eclectic synthesis that dominated the Brazilian art scene until the early 20th century. |

'''Brazilian Romantic painting''' was the leading artistic expression in Brazil during the latter half of the 19th century, coinciding with the [[Second reign (Empire of Brazil)|Second Reign]]. It represented a unique evolution of the [[Romantic movement]]; it diverged significantly from its European counterpart and even the parallel Romantic movement in [[Brazilian literature]]. Characterized by a palatial and restrained aesthetic, it incorporated a strong [[Neoclassicism|neoclassical]] influence and gradually integrated elements of [[Realism (arts)|Realism]], [[Symbolism (arts)|Symbolism]], and other schools, resulting in an eclectic synthesis that dominated the Brazilian art scene until the early 20th century. |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

=== Aesthetic and ideological background === |

=== Aesthetic and ideological background === |

||

[[File:Thomas_Ender_-_View_of_Rio_de_Janeiro.jpg|thumb|Thomas Ender: ''View of Rio de Janeiro'', 1817]] |

[[File:Thomas_Ender_-_View_of_Rio_de_Janeiro.jpg|thumb|Thomas Ender: ''View of Rio de Janeiro'', 1817]] |

||

The roots of Brazilian Romantic painting, though achieving dominance only between 1850 and 1860, can be traced back to the early 19th century, which coincided with the arrival of numerous foreign naturalists on scientific expeditions. Among them were painters and illustrators drawn to Brazil by the burgeoning Romantic emphasis on the value of nature and the allure of the exotic. These artists included [[Thomas Ender]], a participant in the {{interlanguage link|Austro-German Artistic Mission|pt|Missão Artística Austro-Alemã}}. His work focused on depicting "ethnic encounters" within the urban landscape and surrounding areas of [[Rio de Janeiro]]. Another notable figure was [[Johann Moritz Rugendas]], who accompanied the {{interlanguage link|Langsdorff Expedition|pt|Expedição Langsdorff}}. According to Pablo Diener, his work was "possessed of the emotion that [[German Romanticism]] defines as ''Fernweh'', that is, nostalgia for the distant". Rugendas' watercolors, later reproduced as prints, often portrayed indigenous people and individuals of African descent in an idealized manner. However, his works also acknowledged their hardships, demonstrating a degree of social commentary. Furthermore, he exhibited a characteristically Romantic spirit of artistic independence by prioritizing his own creative vision over demands for strict scientific accuracy.<ref>AMBRIZZI, Miguel Luiz. ''Entre olhares - O romântico, o naturalista. Artistas-viajantes na Expedição Langsdorff: 1822-1829''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 4, October, 2008</ref><ref name=":9">RIBEIRO, Monike Garcia. ''A Missão Austríaca no Brasil e as aquarelas do pintor Thomas Ender no século XIX''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume II, n. 2, April 2007</ref> |

|||

[[File:Rugendas_-_Negro_e_Negra_n'uma_Fazenda.JPG|thumb|Rugendas: ''Black man and woman on a farm''. [[The Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Governmental Palaces of the State of São Paulo|Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Governmental Palaces of the State of São Paulo]]]] |

[[File:Rugendas_-_Negro_e_Negra_n'uma_Fazenda.JPG|thumb|Rugendas: ''Black man and woman on a farm''. [[The Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Governmental Palaces of the State of São Paulo|Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Governmental Palaces of the State of São Paulo]]]] |

||

[[Adrien Taunay the Younger|Aimé-Adrien Taunay]], also a participant in the Langsdorff Expedition, was the son of [[Nicolas-Antoine Taunay]], |

[[Adrien Taunay the Younger|Aimé-Adrien Taunay]], also a participant in the Langsdorff Expedition, was the son of [[Nicolas-Antoine Taunay]], who belonged to the [[Missão Artística Francesa|French Artistic Mission]]. His work is noteworthy for its monumental portrayal of nature, specifically depicting landscapes largely untouched by colonization. This approach aligns with the aesthetics of the sublime, a prominent concept within European Romanticism. His paintings incorporated both descriptive and evocative elements, fostering a connection between landscape and historical themes.<ref name=":9" /> Additionally, a significant contribution to the development of Brazilian Romanticism came in 1826 from French consular attaché Ferdinand Denis. He advocated for a shift away from prevailing Classicist tendencies, urging artists to embrace local characteristics. He specifically championed the depiction of nature and native customs, proposing that indigenous people be recognized as the original and most authentic inhabitants of Brazil.<ref name=":7" /> |

||

[[Jean-Baptiste Debret]] |

The artistic trajectory of [[Jean-Baptiste Debret]] merits mention. While his work initially adhered to a strict Neoclassical style, his arrival in Brazil led to a stylistic shift. Debret's art adapted to the climate and informality of the tropical environment. Notably, he was struck by the concept of "''banzo''", a term used by enslaved people to describe their melancholy, and depicted this theme in several watercolors, including the well-known "''Tattooed Black Woman Selling Cashews"''. Debret's extensive [[Watercolor painting|watercolor]] collection, compiled in his publication ''Picturesque and Historical Travel to Brazil'', offers a valuable human and artistic document of Brazilian life during his time. This work marks a significant shift away from Neoclassicism, replaced by an empathetic and naturalistic depiction of enslaved people, reflecting a characteristically Romantic humanist perspective.<ref>DANZIGER, Leila. ''Melancolia à brasileira: A aquarela Negra tatuada vendendo caju, de Debret''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 4, October 2008</ref><ref name=":0">SIQUEIRA, Vera Beatriz. ''Redescobrir o Rio de Janeiro''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume I, no 3, November 2006</ref> |

||

{{Multiple image |

{{Multiple image |

||

| image1 = Debret_negra_vendendo_caju.jpg |

| image1 = Debret_negra_vendendo_caju.jpg |

||

| direction = vertical |

| direction = vertical |

||

| caption1 = Debret: ''Tattooed |

| caption1 = Debret: ''Tattooed Black Woman Selling Cashews'', 1827 |

||

| image2 = Rugendas_-_Sabara.jpg |

| image2 = Rugendas_-_Sabara.jpg |

||

| caption2 = Rugendas: ''View of Sabará'', 1820 |

| caption2 = Rugendas: ''View of Sabará'', 1820 |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

These artists |

These artists arguably played a role in a process of "rediscovery" of Brazil, for both European and Brazilian audiences. The preceding 300 years of colonization had not yielded a particularly vivid portrayal of Brazilian reality. Furthermore, the nascent urbanization process, with its evolving boundaries, provided fertile ground for the depiction of city life, aligning with the unifying spirit traditionally associated with European Romantic landscape painting. However, as scholar Vera Siqueira suggests, a distinctive characteristic of the Brazilian experience lies in: |

||

{{Blockquote|text=All this picturesque vision of the city is related to the European intellectual scheme that, since Rousseau, tends to think of nature as a space of purity, of physical and spiritual health. However, in the travelers' traces we cannot always perceive this type of bourgeois idealization, insofar as it required, by assumption, the civic experience of the modern city. In tropical soil, such absence ends up postulating an insufficient distinction between nature and city, both intimately affected by a sort of original inarticulation. Ideality cannot be transposed either to nature or to the urban experience, which must be placed in the future of a past promise, on the tips of an unrealized history, whose signs remain unknown, to be rediscovered.<ref name=":0" />}} |

{{Blockquote|text=All this picturesque vision of the city is related to the European intellectual scheme that, since Rousseau, tends to think of nature as a space of purity, of physical and spiritual health. However, in the travelers' traces we cannot always perceive this type of bourgeois idealization, insofar as it required, by assumption, the civic experience of the modern city. In tropical soil, such absence ends up postulating an insufficient distinction between nature and city, both intimately affected by a sort of original inarticulation. Ideality cannot be transposed either to nature or to the urban experience, which must be placed in the future of a past promise, on the tips of an unrealized history, whose signs remain unknown, to be rediscovered.<ref name=":0" />}} |

||

Beyond the contributions of itinerant painters and antecedent poets like [[Antônio Peregrino Maciel Monteiro, 2nd Baron of Itamaracá|Maciel Monteiro]],<ref>[http://www.biblio.com.br/defaultz.asp?link=http://www.biblio.com.br/conteudo/MacielMonteiro/MacielMonteiro.htm ''Maciel Monteiro''. Biblioteca Virtual da Literatura]</ref> a group of intellectuals active from the 1830s onwards, following the [[Independence of Brazil]], played a pivotal role in initiating the nation's Romantic movement. Emperor Pedro II emerged as a significant patron of this movement, fostering a series of debates concerning the political, economic, cultural, and social trajectory they envisioned for the new nation. These intellectuals established the groundwork for an interpretive lens through which Brazil would be understood for subsequent decades within official circles. Their efforts resulted in a "mythical configuration" of Brazilian reality, one founded upon the possibilities revealed by political autonomy. This idealized portrayal, emphasizing the nation's natural beauty and indigenous people, would be persistently reproduced throughout the period of 1840 to 1860, coinciding with the consolidation of the Brazilian monarchy.<ref name=":1">TEIXEIRENSE, Pedro Ivo. ''O Jogo das Tradições: A ideia de Brasil nas páginas da Revista Nitheroy (1836)''. Universidade de Brasília, 2006</ref> |

|||

They primarily disseminated their ideas through widely circulated periodicals of the time, including ''Revista Nitheroy'', the ''Jornal de Debates Políticos e Literários'', and the ''Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico do Brasil. A''mong the most active participants in these debates were [[Gonçalves de Magalhães, Viscount of Araguaia|Gonçalves de Magalhães]], [[Francisco de Sales Torres Homem, Viscount of Inhomirim|Francisco de Sales Torres Homem]] and [[Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre, Baron of Santo Ângelo|Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre]].<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

==== The social, economic and cultural conjuncture ==== |

==== The social, economic and cultural conjuncture ==== |

||

[[File:Rugendas_-_Defrichement_d_une_Foret.jpg|thumb|Rugendas: ''Devastation of the jungle'', 1820]] |

[[File:Rugendas_-_Defrichement_d_une_Foret.jpg|thumb|Rugendas: ''Devastation of the jungle'', 1820]] |

||

Prior to Brazilian independence, the economic and social landscape reflected a focus on resource extraction. Natural wealth, such as brazilwood, gold, and diamonds, was primarily directed towards Portugal. Until the arrival of King [[John VI of Portugal|John VI]] in 1808, Brazil remained a colony with the primary objective of extracting resources for the benefit of the metropole. Higher education was actively discouraged, and resources for even basic education for the resident population were scarce. King John VI's arrival marked a shift in policy. Facing uncertain circumstances regarding his return to Portugal, the King initiated a period of greater international openness and pursued a more progressive approach to economic development. However, this period of relative prosperity was short-lived. After the [[Liberal Revolution of 1820|Liberal Revolution]] in Portugal, King John VI was forced to return, and the Portuguese revolutionaries attempted to reimpose the previous colonial model. This attempt ultimately failed in the face of Brazilian independence.<ref name=":7" /> |

|||

The arrival of the Portuguese court in Rio de Janeiro in 1808 did have some artistic repercussions. One notable development was the establishment of the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts, a precursor to the [[Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (Brazil)|Imperial Academy]], which contributed to a temporary flourishing of cultural life in Rio de Janeiro.<ref name=":7" /> However, the departure of King John VI in 1821 had a swift and significant impact. The process of securing Brazilian independence also imposed a heavy financial burden on the newly formed empire. King John VI's withdrawal of a substantial sum from the [[Banco do Brasil|Bank of Brazil]] upon his departure effectively triggered a near-bankruptcy. Furthermore, recognition of Brazil's independence by England came at a cost of two million pounds. Moreover, the absence of a well-established tradition of higher-level art education and practice within the country limited artistic development. Even the local elites, by and large, exhibited a provincial outlook in artistic matters.<ref>LOYOLA, Leandro. ''Dom João VI empurrava as coisas com a barriga''. Revista Época, edição nº 506, 28/01/2008</ref><ref>''Independência do Brasil''. Linha Aberta. Edição 121, setembro de 2008.</ref><ref>MARIZ, Vasco. ''História da Música no Brasil''. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2006. pp.65-66.</ref><ref name=":7" /> |

|||

The situation improved |

The situation improved during the period of political stabilization known as the [[Second reign (Empire of Brazil)|Second Reign]]. However, imperial patronage of the arts remained modest. The overall cultural environment became increasingly marked by a sense of fiscal restraint. In contrast to the opulence of European courts, Brazilian imperial residences resembled the grand homes of minor nobility. Even the crown for Pedro II's coronation was crafted using materials from his father's crown, reflecting the budgetary limitations. The Academy's annual expenditures, including scholarships, salaries, equipment and building maintenance, and pensions, did not surpass eight hundred and twenty million ''[[Brazilian real (old)|réis]]''. This sum was comparable to the imperial family's summer expenses in Petrópolis and half the cost of maintaining the imperial stables. The domestic art market remained restricted throughout this period, with the imperial family serving as the primary patrons.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8" /> |

||

== The creation of a face for Brazil == |

== The creation of a face for Brazil == |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Victor_Meirelles_-_Pedro_II.jpg|left|thumb|272x272px|Victor Meirelles: ''Dom Pedro II'', 1864. [[São Paulo Museum of Art]]]]Brazilian Romanticism reached its peak during a period when the movement in Europe had already entered its later stages, characterized by a shift towards catering to the tastes of the affluent and established middle class. This 'bourgeois' Romanticism had largely abandoned the earlier emphasis on egalitarianism inspired by the French Revolution and the robust energy associated with Napoleonic imperialism. It was the more conservative and sentimental iteration of Romanticism that primarily influenced the development of Brazilian Romantic painting. This artistic movement flourished almost exclusively within the confines of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":2">FERNANDES, Cybele V. F. ''A construção simbólica da nação: A pintura e a escultura nas Exposições Gerais da Academia Imperial das Belas Artes''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume II, n. 4, October 2007</ref> |

||

[[File:Victor_Meirelles_-_Pedro_II.jpg|left|thumb|272x272px|Victor Meirelles: ''Dom Pedro II'', 1864. [[São Paulo Museum of Art]]]] |

|||

Despite its structural similarities to the French Academy, the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro faced significant challenges, as it lacked a well-established tradition and operated with a precarious structure and limited resources. Furthermore, Brazilian society at large did not fully recognize the value of the Academy's educational project. Similarly, many aspiring artists, with a few notable exceptions, lacked the foundational education to fully benefit from the Academy's instruction. Documents from the period consistently highlight recurring difficulties, including a shortage of qualified instructors and equipment, along with the inadequate preparation of students, some of whom exhibited basic literacy deficiencies. The Academy's achievements were largely contingent upon the personal patronage of Emperor Pedro II. A strong advocate for the arts and sciences, he positioned the Academy as the artistic engine of his nationalist project.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":2" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | Brazilian Romanticism reached its peak when the movement |

||

Although it was built similarly to the French academy, unlike the latter, the Brazilian one lacked its own consistent tradition and was just barely established, with a precarious functioning structure and lacking resources. Neither society in general was attentive enough to recognize the value of the educational project it presented, nor were the artists ready to take advantage of it as they could if they had received a more complete and effective basic education, with a few notable exceptions. Documents from the period repeatedly deplored the shortage of teachers and equipment, the poor preparation of the students - some were barely literate - and reported a host of other difficulties throughout its history. What this school was able to produce depended in large part on the personal [[patronage]] of emperor Pedro II, who had a great interest in the arts and sciences, and who made it the executive arm in the arts of his nationalist project.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":2" /> |

|||

[[File:Pedro_Américo_-_Independência_ou_Morte_-_cores_ajustadas.jpg|thumb|250x250px|Pedro Américo: ''Independence or Death'', 1888. [[Museu do Ipiranga]]]] |

[[File:Pedro_Américo_-_Independência_ou_Morte_-_cores_ajustadas.jpg|thumb|250x250px|Pedro Américo: ''Independence or Death'', 1888. [[Museu do Ipiranga]]]] |

||

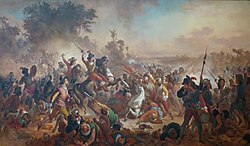

[[File:Victor_Meirelles_-_'Battle_of_Guararapes',_1879,_oil_on_canvas,_Museu_Nacional_de_Belas_Artes,_Rio_de_Janeiro.JPG|thumb|250x250px|Victor Meirelles: ''Battle of Guararapes'', 1879. [[Museu Nacional de Belas Artes|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

[[File:Victor_Meirelles_-_'Battle_of_Guararapes',_1879,_oil_on_canvas,_Museu_Nacional_de_Belas_Artes,_Rio_de_Janeiro.JPG|thumb|250x250px|Victor Meirelles: ''Battle of Guararapes'', 1879. [[Museu Nacional de Belas Artes|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

||

Despite |

Despite its limitations, the Imperial Academy entered its most stable and productive period during the Second Reign. Under Emperor Pedro II's direct supervision, the Academy achieved a greater degree of operational stability. This period of improved resources provided fertile ground for the flourishing of Brazilian Romantic painting, fostering the emergence of prominent figures such as [[Victor Meirelles]], [[Pedro Américo]], [[Rodolfo Amoedo]] and [[José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior|Almeida Júnior]]. These artists built upon the foundational work of [[Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre, Baron of Santo Ângelo|Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre]], whose contributions were instrumental in developing a symbolic visual language capable of unifying the nationalist movement active during this period. Nationalist aspirations sought to establish Brazil's equivalence with the most "civilized" European states. Januário da Cunha Barbosa, secretary of the [[Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute]], echoed this sentiment, arguing against foreigners shaping Brazil's historical narrative.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3">SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. ''Romantismo Tropical: A estetização da política e da cidadania numa instituição imperial brasileira''. Penélope, 2000</ref> |

||

The artistic program of the Imperial Academy operated within a well-defined ideological framework and prioritized specific themes. This approach differed from the earlier, more independent and passionate works created by the traveling artists of the early 19th century. Their works, primarily directed towards European scientific circles interested in natural history, did not establish a lasting artistic school in Brazil. Their influence, if any, seems to be limited to the international promotion of Brazil's natural beauty, which would later attract a greater number of artists who would have a more significant impact on the development of a distinct Brazilian artistic identity. The Academy's focus centered on portraiture, particularly of members of the new ruling house, and historical scenes depicting pivotal national events such as battles that secured Brazil's territorial integrity and sovereignty, the independence movement, and the role of indigenous people. Brazilian Romantic painting was characterized by a clear nationalistic sentiment, a didactic and progressive inclination, and a consistent idealism evident in the selection of themes and their expression. A notable shift occurred in the favored artistic techniques. The Davidian model of Neoclassical painting, emphasizing line over color, gave way to a greater emphasis on color and chiaroscuro (light and shadow). This change reflected a new sensibility, distinct from Neoclassicism, that was better suited to portraying Brazilian particularities. It is worth noting the divergence between Brazilian Romantic painting and literary Romanticism.The Academy, funded by the state, did not embrace the Byronic influence that pervaded Brazilian literature. Emperor Pedro II's nationalist project was inherently optimistic and fundamentally opposed to the ultra-sentimental and morbid characteristics of the second generation of Romantic writers, often referred to as the "bohemians" who grappled with the ''mal du siècle''.<ref name=":4">DUQUE ESTRADA, Luiz Gonzaga. ''A arte brasileira''. Rio de Janeiro: H. Lombaerts, 1888</ref><ref name=":3" /> |

|||

[[File:Belmiro_de_Almeida_-_Arrufos,_1887.jpg|left|thumb|180x180px|Belmiro de Almeida: ''The Spat'', 1887. [[National Museum of Fine Arts (Brazil)|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

[[File:Belmiro_de_Almeida_-_Arrufos,_1887.jpg|left|thumb|180x180px|Belmiro de Almeida: ''The Spat'', 1887. [[National Museum of Fine Arts (Brazil)|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

||

While the Imperial Academy's emphasis on rigid aesthetic principles and its reliance on government approval did restrict the expression of artistic independence and originality, a hallmark of European Romanticism. Additionally, the movement lacked the contestatory and revolutionary spirit often associated with the early, more passionate phases of European Romanticism. However, attributing the restrained and conventional character of Brazilian Romantic painting solely to official constraints would be an oversimplification. As previously noted, the delayed emergence of Romanticism in Brazil meant it was primarily influenced by the waning stages of the movement in Europe, particularly French [[L'art pompier|''Pompier'' art]], which is characterized by its bourgeois nature, emphasis on conformity, eclecticism, and sentimentality.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Although a scholarship program offered travel to Europe for the most promising artists, such travel was intended to broaden their artistic horizons within certain parameters. Recommendations were made to avoid exposure to potentially disruptive influences, such as the works of [[Eugène Delacroix]]. His art, with its emphasis on individual liberty, could have conceivably cast doubt on the legitimacy of the newly established Brazilian government following its long period of dependence on Portugal. In this context, a notable characteristic of Brazilian Romanticism was a systematic disinclination to engage with Portuguese artistic traditions. Brazilian artists instead sought educational and inspirational models in France, and to a lesser extent, in Italy.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

[[File:Nicola_Facchinetti_-_Lagoa_Rodrigo_de_Freitas,_Rio_de_Janeiro,_ca._1884.jpg|thumb|250x250px|Nicola Facchinetti: ''Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Rio de Janeiro'', 1884. [[Museu Nacional de Belas Artes|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

[[File:Nicola_Facchinetti_-_Lagoa_Rodrigo_de_Freitas,_Rio_de_Janeiro,_ca._1884.jpg|thumb|250x250px|Nicola Facchinetti: ''Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Rio de Janeiro'', 1884. [[Museu Nacional de Belas Artes|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

||

Despite efforts to construct a national identity, Brazilian elites grappling with this process were not without blind spots regarding the pitfalls of emulating foreign models. Scholar [[Lilia Moritz Schwarcz|Lilia Schwarcz]] argues that a paradox emerged in Brazil's attempt to develop its own visual iconography. On the one hand, Emperor Pedro II's nationalist project demonstrably possessed sincerity and arose from a clear need. However, his understanding of progress and civilization remained firmly rooted in European models. Consequently, the image of Brazil he sought to present to the world was inevitably selective, favoring portrayals of the landscape that adhered to European formal styles and overlooking negative social realities such as [[slavery]]. In Brazilian academic painting, with a few exceptions, the depiction of Black people largely remained confined to their role as anonymous figures within the landscape. Only with the growing momentum of the abolitionist movement and the subsequent republican era did Black figures begin to take center stage. It is important to note that by this point, Romanticism as an artistic movement was nearing its end, with new aesthetic schools gaining prominence.<ref>LIMA, Heloisa Pires. ''A presença negra nas telas: visita às exposições do circuito da Academia Imperial de Belas Artes na década de 1880''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 1, January 2008 </ref><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8" /> |

|||

[[File:Ultimo_tamoio_1883.jpg|thumb|250x250px|Rodolfo Amoedo: ''The Last Tamoio'', 1883. [[Museu Nacional de Belas Artes|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

[[File:Ultimo_tamoio_1883.jpg|thumb|250x250px|Rodolfo Amoedo: ''The Last Tamoio'', 1883. [[Museu Nacional de Belas Artes|National Museum of Fine Arts]]]] |

||

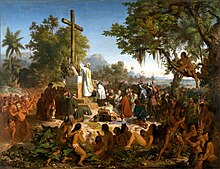

Indigenous people fared better in Brazilian Romantic art compared to Black portrayals. Following centuries of conflict and violence, the government now promoted their idealized depiction. These portrayals presented them as the embodiment of a pure culture living in harmony with their environment and positioned them as the other recognized ethnic group contributing to the formation of the new nation. This gave rise to the Indianist movement, a prominent channel for expressing Romantic ideals, finding even stronger resonance in literature and [[graphic arts]]. The emphasis on indigenous culture was reflected even in Dom Pedro II's regalia. His ceremonial mace incorporated toucan feathers, drawing inspiration from the featherwork of Indigenous leaders.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8" /> |

|||

<blockquote>In the images of the time, the indigenism ceased to be only an aesthetic model, to be incorporated into the very representation of royalty: the empire performed, then, an "American mimesis" (Alencastro, 1980:307). Thus, alongside classical allegories appear almost white and idealized natives in a tropical environment, or else cherubs and allegories that sharing space with the natives come to embody a mythical and authentic past.<ref>SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. ''Romantismo tropical ou o Imperador e seu círculo ilustrado''. USP</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Beyond the core thematic areas of historical scenes, landscapes, portraits of the imperial family, and depictions of Indigenous and working-class people, Brazilian Romantic painting encompassed a wider range of subjects. This included still lifes, genre scenes (everyday life), religious works, and even occasional forays into [[myth]]ological [[Allegory|allegories]], Orientalist themes, and medievalism. These diverse subjects enriched the panorama of Brazilian Romantic art.<ref name=":5">SÁ, Ivan Coelho de. [http://www.dezenovevinte.net/ensino_artistico/ea_ivan.htm "O Processo de Desacademização através dos Estudos de Modelo Vivo na Academia/Escola de Belas Artes do Rio de Janeiro"]. ''19&20'', Rio de Janeiro, v. IV, n. 3, July 2009</ref><ref>LEITE, Reginaldo da Rocha. [http://www.dezenovevinte.net/ensino_artistico/txt_reginaldo.htm "A Pintura de Temática Religiosa na Academia Imperial das Belas Artes: Uma Abordagem Contemporânea"]. ''19&20'', Rio de Janeiro, v. II, n. 1, January 2007</ref> The influence of Romanticism and the academic model it championed persisted in Brazilian painting until the early 20th century, despite the emergence of new artistic movements such as [[Realism (arts)|Realism]], [[Naturalism (philosophy)|Naturalism]], [[Impressionism]] and [[Symbolism (arts)|Symbolism]] in the late 19th century. According to scholar Coelho de Sá, the final decades of the 19th century witnessed a "process of de-academization," where artistic instruction gradually departed from traditional methodologies. These methodologies had been centered on the study of the human figure, drawing techniques, and Renaissance illusionistic color palettes. This shift also involved a move away from the ideological, technical, and formal constraints of Romanticism.<ref name=":5" /> |

|||

== Central names == |

== Central names == |

||

| Line 89: | Line 85: | ||

Porto-Alegre was a polymorphous talent; diplomat, art critic, historian, architect, set designer, poet and writer, he left little work in painting, although he was the mentor of the next generation and perhaps the most typical of all the Romantics. His major importance was in organizing the academy, promoting nationalism, defending art as a relevant social force, and encouraging progress in general. The founding of the periodical Nitheroy in [[1836]] is regarded as one of the initial milestones of Brazilian Romanticism.<ref>''Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre''. 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte.</ref> In a speech at the solemn session of the academy in [[1855]] he said: |

Porto-Alegre was a polymorphous talent; diplomat, art critic, historian, architect, set designer, poet and writer, he left little work in painting, although he was the mentor of the next generation and perhaps the most typical of all the Romantics. His major importance was in organizing the academy, promoting nationalism, defending art as a relevant social force, and encouraging progress in general. The founding of the periodical Nitheroy in [[1836]] is regarded as one of the initial milestones of Brazilian Romanticism.<ref>''Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre''. 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte.</ref> In a speech at the solemn session of the academy in [[1855]] he said: |

||

<blockquote>The new classes, that the Imperial Government offers |

<blockquote>The new classes, that the Imperial Government offers [...] today to the youth in this education reform, will open a new era for the Brazilian industry, and give the youth a secure subsistence. They will give artifice a new light, denied for thirty years by those who live off a part of their sweat; they will subtract another portion of the debt incurred in Ypiranga; because a nation is only independent when it exchanges the products of its intelligence, when it satisfies itself, or when it raises its national conscience, and leaves the tulmuthous arena, where internal and external contradictions are debated, to occupy itself with its material progress as the basis of its moral happiness. In these new classes he will have a fertile spring in all his future, a new view to study nature and admire its infinite variety and beauty. [...] Young people, leave the prejudice of longing for public jobs, the telethon of the offices, which ages you prematurely, and condemns you to poverty and to a continuous slavery; apply yourselves to arts and industry: the arm that was born to be an ass or a trowel should not handle the pen. Banish the prejudices of a decadent race, and the maxims of laziness and corruption: the artist, the artificer and the craftsman are as good workers in the building of the sublime nation as the priest, the magistrate and the soldier: work is strength, strength intelligence, and intelligence power and divinity.<ref>PORTO-ALEGRE, Manoel de Araujo. ''Discurso pronunciado em sessão Solene de 2 de junho de 1855 na Academia das Bellas Artes pelo Sr. Comdor. Manoel de Araújo Porto Alegre por occasião do estabelecimento das aulas de mathematicas, estheticas, etc, etc.''</ref></blockquote> |

||

[[File:Americo-avaí.jpg|thumb|Pedro Américo: ''The Battle of Avaí'', 1872–1877. National Museum of Fine Arts]] |

[[File:Americo-avaí.jpg|thumb|Pedro Américo: ''The Battle of Avaí'', 1872–1877. National Museum of Fine Arts]] |

||

| Line 115: | Line 111: | ||

Other notable Brazilians also worked along romantic lines, at least part of their careers. Among them, Jerônimo José Telles Júnior, Aurélio de Figueiredo, [[Henrique Bernardelli]], [[Antônio Parreiras]], [[Firmino Monteiro|Antônio Firmino Monteiro]], [[João Zeferino da Costa]], [[Belmiro de Almeida]], [[Eliseu Visconti]], [[Arthur Timótheo da Costa]], [[Pedro Weingärtner]], and [[Décio Villares]].{{Obsolete source|date=October 2022}} |

Other notable Brazilians also worked along romantic lines, at least part of their careers. Among them, Jerônimo José Telles Júnior, Aurélio de Figueiredo, [[Henrique Bernardelli]], [[Antônio Parreiras]], [[Firmino Monteiro|Antônio Firmino Monteiro]], [[João Zeferino da Costa]], [[Belmiro de Almeida]], [[Eliseu Visconti]], [[Arthur Timótheo da Costa]], [[Pedro Weingärtner]], and [[Décio Villares]].{{Obsolete source|date=October 2022}} |

||

In addition to the previously mentioned artist-explorers who played a pioneering role in Brazilian Romanticism, a significant number of foreign artists contributed to the movement during its peak and the Imperial Academy's operation. These artists, some of whom resided permanently in Brazil while others were transient, played a vital role in historical painting and landscape painting. They also served as instructors, disseminating artistic practices. Notable examples include landscape painters [[Henri Nicolas Vinet]], [[Georg Grimm]], and Nicola Antonio Facchinetti. Historical painters included [[Edoardo De Martino|Edoardo de Martino]], [[Giovanni Battista Castagneto]], José Maria de Medeiros, Pedro Peres, Louis-Auguste Moreaux, François-René Moreaux, and Augusto Rodrigues Duarte.<ref>SILVA, Anderson Marinho da. [https://repositorio.ufba.br/handle/ri/21408 ''Manoel Ignácio de Mendonça Filho e a pintura de marinha na Bahia'']. Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2017, pp. 57-80</ref><ref>OLIVEIRA, Raphael Braga de. [https://www.historia.uff.br/academico/media/aluno/2400/projeto/RAPHAEL_BRAGA_DE_OLIVEIRA_GCeVfGK.pdf ''Pintura de paisagem e guerra: Eduardo De Martino e os mundos da arte no Brasil (1868-1877)'']. Mestrado. Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2020, pp. 26; 129</ref> The landscape genre held particular appeal for foreign artists. Drawn to the exotic and picturesque qualities of Brazil's natural world, with its unfamiliar flora and fauna, they made significant contributions to the development of landscape painting in Brazil.<ref>OLIVEIRA, p. 135</ref> |

|||

== Legacy == |

== Legacy == |

||

[[File:Johann_Georg_Grimm_1884,_Vista_da_Ponta_de_Icaraí.jpg|thumb|Georg Grimm: ''View from Ponta de Icaraí'', 1884. Sergio Sahione Fadel Collection]] |

[[File:Johann_Georg_Grimm_1884,_Vista_da_Ponta_de_Icaraí.jpg|thumb|Georg Grimm: ''View from Ponta de Icaraí'', 1884. Sergio Sahione Fadel Collection]] |

||

Similar to the ongoing debate among art critics regarding the precise definition and chronological boundaries of international Romanticism, the analysis of Brazilian 19th-century painting remains nuanced and subject to ongoing discussion.<ref>FORWARD, Stephanie. ''Legacy of the Romantics''. The Open University. BBC</ref> Some scholars question the artistic merit of Brazilian Romantic painting and even hesitate to classify it as truly Romantic. They point to the presence of clear Neoclassical and realist elements, the influence of government control, and the deep entanglement with the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. This critical perspective dominated art historical discourse until the latter part of the 20th century. However, more recent scholarship conducted within a broader historical context acknowledges the presence of a well-defined Romantic style in Brazilian art, albeit confined to the realm of "academic Romanticism." This style played a significant role during its historical period.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

The late 19th century saw a rise in criticism against both the Imperial Academy and the Romantic movement. A younger generation of writers, including [[Gonzaga Duque]] and [[Angelo Agostini]], targeted what they perceived as the weaknesses of Brazilian Romanticism. They criticized its utopian idealism as weak, elitist, and outdated. They further argued that it was subservient to European styles, irrelevant to national culture, and out of touch with contemporary trends. In their eagerness to see rapid artistic progress in Brazil, these critics lacked the necessary historical perspective to offer a balanced judgment. Their focus on the immediate context and their own surroundings limited their understanding of the historical forces that had shaped 19th-century Brazilian art. They also underestimated the challenges of fostering a large-scale cultural renewal in a nation still consolidating its independence. Furthermore, they overlooked the enduring influence of Brazil's Baroque heritage, which continued to manifest in various regional artistic expressions and popular culture, largely unaffected by developments in Rio de Janeiro.<ref>CARDOSO, Rafael. ''A Academia Imperial de Belas Artes e o Ensino Técnico''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 1, January 2008</ref><ref>EULÁLIO, Alexandre. ''O Século XIX''. In ''Tradição e Ruptura. Síntese de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras''. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 1984-85. pp. 118-119</ref><ref>DUQUE ESTRADA. ''A Arte Brasileira: Progresso VII: Belmiro de Almeida''. Rio de Janeiro: H. Lombaerts, 1888 </ref><ref>QUÍRICO, Tamara. ''Comentários e críticas de Gonzaga Duque a Pedro Américo''. In: 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume I, n. 1, May 2006</ref> |

|||

Despite |

Despite ongoing critiques, Brazilian Romantic painting produced in the latter half of the 19th century can be viewed as a significant achievement. Emerging from a nascent artistic tradition, it marked a turning point and left a lasting impression on the nation's collective memory. This artistic movement is arguably symbolic of Brazil's entry into modernity. The public impact of works like Victor Meirelles' and Pedro Américo's depictions of historical battles was undeniable. Exhibited at the 1879 Salon, these paintings drew a remarkable audience exceeding 292,000 visitors over a 62-day period.This level of engagement remains unmatched even by contemporary events like the [[São Paulo Art Biennial]]s, considering Rio de Janeiro's population of just over 300,000 at the time.<ref>CARDOSO, Rafael. ''Ressuscitando um Velho Cavalo de Batalha: Novas Dimensões da Pintura Histórica do Segundo Reinado''. 19&20 - A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume II, n. 3, July 2007</ref> Brazil's first foray into the prestigious [[Salon (Paris)|Paris Salon]] occurred with a Romantic work, "''[[The First Mass in Brazil (Victor Meirelles)|The First Mass in Brazil]]''". Similarly, "''The Battle of Avaí''" marked the first instance of a Brazilian artist achieving international recognition, albeit modest, for their work. These developments represented initial steps towards Brazil's active participation in the global art scene. Many key Romantic paintings, including "''Moema''", "''The Last Tamoio''", "''[[Independence or Death (painting)|Independence or Death]]!''", and "''The Emperor's Speech''", have become iconic visual representations of Brazilian history. Their enduring popularity is evidenced by their continued inclusion in school textbooks, reaching millions of students each year. This widespread exposure speaks to the artistic merit of these works, the effectiveness of the Romantic style in conveying historical narratives, and the foresight of the government's artistic project that fostered their creation. The Romantic movement's portrayal of Indigenous people in a more sympathetic light, along with its positive depictions of other working-class figures, can be seen as an early step towards greater national integration. Furthermore, the emphasis on nationalism within Romantic art arguably laid the groundwork for the modern conception of Brazilian identity.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8" /> |

||

== Gallery == |

== Gallery == |

||

<gallery> |

<center><gallery> |

||

File:Nicolas-Antoine Taunay - Tropeiros negociando um cavalo.jpg|Nicolas-Antoine Taunay: ''[[Tropeiro]]s trading a horse''. Imperial Museum of Brazil |

File:Nicolas-Antoine Taunay - Tropeiros negociando um cavalo.jpg|Nicolas-Antoine Taunay: ''[[Tropeiro]]s trading a horse''. Imperial Museum of Brazil |

||

File:Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre - Grota 2.jpg|Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre: ''Cave''. National Museum of Fine Arts |

File:Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre - Grota 2.jpg|Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre: ''Cave''. National Museum of Fine Arts |

||

| Line 141: | Line 137: | ||

File:Parreiras-ventania-pinac.jpg|Antonio Parreiras: ''The Gale'', 1888 |

File:Parreiras-ventania-pinac.jpg|Antonio Parreiras: ''The Gale'', 1888 |

||

File:Timotheo-aleluia.jpg|Timótheo da Costa: ''Before Hallelujah'', 1907. National Museum of Fine Arts |

File:Timotheo-aleluia.jpg|Timótheo da Costa: ''Before Hallelujah'', 1907. National Museum of Fine Arts |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery></center> |

||

== References ==<!-- Inline citations added to your article will automatically display here. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WP:REFB for instructions on how to add citations. --> |

== References ==<!-- Inline citations added to your article will automatically display here. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WP:REFB for instructions on how to add citations. --> |

||

Revision as of 14:40, 16 July 2024

Brazilian Romantic painting was the leading artistic expression in Brazil during the latter half of the 19th century, coinciding with the Second Reign. It represented a unique evolution of the Romantic movement; it diverged significantly from its European counterpart and even the parallel Romantic movement in Brazilian literature. Characterized by a palatial and restrained aesthetic, it incorporated a strong neoclassical influence and gradually integrated elements of Realism, Symbolism, and other schools, resulting in an eclectic synthesis that dominated the Brazilian art scene until the early 20th century.

Brazilian Romantic painting was heavily influenced by a nationalist movement spearheaded by Emperor Pedro II. Seeking to unify the culturally diverse and geographically vast nation following independence, he recognized the potential of art to forge a cohesive national identity. This artistic movement aimed to project an image of Brazil as a civilized and progressive nation on the world stage. This nationalist sentiment manifested in three primary artistic themes: historical reenactments, portrayals of nature and the people, and the reevaluation of the indigenous figure. These themes resulted in a substantial corpus of artworks that continue to hold a significant place in Brazilian museums. The symbolism employed within these works is acknowledged to have played a considerable role in the formation of a national identity.[1][2]

International Romanticism

The artistic movement known as Pictorial Romanticism, which flourished in Europe from the mid-18th to the late 19th centuries, defies a singular definition. While commonly conceived as a unified movement, critical discourse lacks consensus on both the defining characteristics of a Romantic style and the very existence of such a movement. Despite this lack of agreement, a unifying element appears to be the emphasis on the individual artist's unique perspective and creative vision. Romantic artists, characterized by a heightened awareness of their inner world and emotions, perceived themselves as free from past artistic constraints. Their artistic judgments were not guided by prevailing rationalism or predetermined aesthetic programs, but rather by their own subjective experience, which could encompass a range of emotions, including a yearning for a connection with nature or the transcendent.[3] According to Baudelaire:

Romanticism is not found in the choice of themes nor in its objective truth, but in the way of feeling. For me, Romanticism is the most recent and current expression of beauty. And whoever speaks of Romanticism speaks of modern art, that is to say, intimacy, spirituality, color and tendency to infinity, expressed by all the means that the arts have at their disposal.[4][5]

The emphasis on individual expression within Romanticism sometimes manifested in artistic projects pushing the boundaries of convention. These projects embraced the unconventional, the exotic, and the eccentric, occasionally bordering on the melodramatic, morbid, or even hysterical. Furthermore, a prevalent sentiment of the era, often referred to as the mal du siècle, characterized by a sense of emptiness, futility, and melancholic dissatisfaction, permeated the works of many artists. This is evidenced by Géricault's statement, "whatever I do, I wish I had done differently," reflecting this prevailing mood.[6][7]

Romanticism's emphasis on nature often manifested in a pantheistic worldview and a novel approach to landscape design. Furthermore, the movement's focus on historical context revolutionized the understanding of humanity's place within history and the value of established institutions like the State and the Church. This humanistic idealism, seeking social reform, led many Romantics to create sensitive portrayals of the people, their customs, folklore, and history. These portrayals arguably served as a foundation for the emergence or reinforcement of nationalist movements in many countries. However, following the tumultuous period of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire, the early Romantics' visionary, humanistic, and contestatory spirit waned. Subject matter became less significant compared to technical skill and formal concerns. Many artists retreated into idealized portrayals of the East or the Middle Ages, while others succumbed to a bourgeois sentimentality and conventionality, emphasizing the decorative, exotic, and picturesque. Technically, Romantic painting departed from the Neoclassical emphasis on line over color and rational composition. Romantics favored more evocative compositions designed to elicit a stronger emotional response. Color and chiaroscuro (use of light and shadow) became more prominent elements, contributing to the creation of suggestive atmospheres and lighting effects.[8]

Romanticism emerges as a multifaceted and internally conflicted artistic movement. While demonstrably influenced by, and in some ways an extension of, Classicism, it also stands in opposition to certain aspects of that tradition. The inherent tension is further reflected in the movement's embrace of individualism, which fostered a remarkable diversity of aesthetic approaches and ideological perspectives. This emphasis on the individual artist's vision arguably contributed to a sense of rootlessness, alienation, and misunderstanding among Romantics. As Hauser observes, the intensely personal nature of artistic goals and the highly individualized criteria for artistic merit within Romanticism make the designation of distinct schools within the movement somewhat problematic.[9]

The Brazilian version

Aesthetic and ideological background

The roots of Brazilian Romantic painting, though achieving dominance only between 1850 and 1860, can be traced back to the early 19th century, which coincided with the arrival of numerous foreign naturalists on scientific expeditions. Among them were painters and illustrators drawn to Brazil by the burgeoning Romantic emphasis on the value of nature and the allure of the exotic. These artists included Thomas Ender, a participant in the Austro-German Artistic Mission. His work focused on depicting "ethnic encounters" within the urban landscape and surrounding areas of Rio de Janeiro. Another notable figure was Johann Moritz Rugendas, who accompanied the Langsdorff Expedition. According to Pablo Diener, his work was "possessed of the emotion that German Romanticism defines as Fernweh, that is, nostalgia for the distant". Rugendas' watercolors, later reproduced as prints, often portrayed indigenous people and individuals of African descent in an idealized manner. However, his works also acknowledged their hardships, demonstrating a degree of social commentary. Furthermore, he exhibited a characteristically Romantic spirit of artistic independence by prioritizing his own creative vision over demands for strict scientific accuracy.[10][11]

Aimé-Adrien Taunay, also a participant in the Langsdorff Expedition, was the son of Nicolas-Antoine Taunay, who belonged to the French Artistic Mission. His work is noteworthy for its monumental portrayal of nature, specifically depicting landscapes largely untouched by colonization. This approach aligns with the aesthetics of the sublime, a prominent concept within European Romanticism. His paintings incorporated both descriptive and evocative elements, fostering a connection between landscape and historical themes.[11] Additionally, a significant contribution to the development of Brazilian Romanticism came in 1826 from French consular attaché Ferdinand Denis. He advocated for a shift away from prevailing Classicist tendencies, urging artists to embrace local characteristics. He specifically championed the depiction of nature and native customs, proposing that indigenous people be recognized as the original and most authentic inhabitants of Brazil.[2]

The artistic trajectory of Jean-Baptiste Debret merits mention. While his work initially adhered to a strict Neoclassical style, his arrival in Brazil led to a stylistic shift. Debret's art adapted to the climate and informality of the tropical environment. Notably, he was struck by the concept of "banzo", a term used by enslaved people to describe their melancholy, and depicted this theme in several watercolors, including the well-known "Tattooed Black Woman Selling Cashews". Debret's extensive watercolor collection, compiled in his publication Picturesque and Historical Travel to Brazil, offers a valuable human and artistic document of Brazilian life during his time. This work marks a significant shift away from Neoclassicism, replaced by an empathetic and naturalistic depiction of enslaved people, reflecting a characteristically Romantic humanist perspective.[12][13]

These artists arguably played a role in a process of "rediscovery" of Brazil, for both European and Brazilian audiences. The preceding 300 years of colonization had not yielded a particularly vivid portrayal of Brazilian reality. Furthermore, the nascent urbanization process, with its evolving boundaries, provided fertile ground for the depiction of city life, aligning with the unifying spirit traditionally associated with European Romantic landscape painting. However, as scholar Vera Siqueira suggests, a distinctive characteristic of the Brazilian experience lies in:

All this picturesque vision of the city is related to the European intellectual scheme that, since Rousseau, tends to think of nature as a space of purity, of physical and spiritual health. However, in the travelers' traces we cannot always perceive this type of bourgeois idealization, insofar as it required, by assumption, the civic experience of the modern city. In tropical soil, such absence ends up postulating an insufficient distinction between nature and city, both intimately affected by a sort of original inarticulation. Ideality cannot be transposed either to nature or to the urban experience, which must be placed in the future of a past promise, on the tips of an unrealized history, whose signs remain unknown, to be rediscovered.[13]

Beyond the contributions of itinerant painters and antecedent poets like Maciel Monteiro,[14] a group of intellectuals active from the 1830s onwards, following the Independence of Brazil, played a pivotal role in initiating the nation's Romantic movement. Emperor Pedro II emerged as a significant patron of this movement, fostering a series of debates concerning the political, economic, cultural, and social trajectory they envisioned for the new nation. These intellectuals established the groundwork for an interpretive lens through which Brazil would be understood for subsequent decades within official circles. Their efforts resulted in a "mythical configuration" of Brazilian reality, one founded upon the possibilities revealed by political autonomy. This idealized portrayal, emphasizing the nation's natural beauty and indigenous people, would be persistently reproduced throughout the period of 1840 to 1860, coinciding with the consolidation of the Brazilian monarchy.[15]

They primarily disseminated their ideas through widely circulated periodicals of the time, including Revista Nitheroy, the Jornal de Debates Políticos e Literários, and the Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico do Brasil. Among the most active participants in these debates were Gonçalves de Magalhães, Francisco de Sales Torres Homem and Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre.[15]

The social, economic and cultural conjuncture

Prior to Brazilian independence, the economic and social landscape reflected a focus on resource extraction. Natural wealth, such as brazilwood, gold, and diamonds, was primarily directed towards Portugal. Until the arrival of King John VI in 1808, Brazil remained a colony with the primary objective of extracting resources for the benefit of the metropole. Higher education was actively discouraged, and resources for even basic education for the resident population were scarce. King John VI's arrival marked a shift in policy. Facing uncertain circumstances regarding his return to Portugal, the King initiated a period of greater international openness and pursued a more progressive approach to economic development. However, this period of relative prosperity was short-lived. After the Liberal Revolution in Portugal, King John VI was forced to return, and the Portuguese revolutionaries attempted to reimpose the previous colonial model. This attempt ultimately failed in the face of Brazilian independence.[2]

The arrival of the Portuguese court in Rio de Janeiro in 1808 did have some artistic repercussions. One notable development was the establishment of the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts, a precursor to the Imperial Academy, which contributed to a temporary flourishing of cultural life in Rio de Janeiro.[2] However, the departure of King John VI in 1821 had a swift and significant impact. The process of securing Brazilian independence also imposed a heavy financial burden on the newly formed empire. King John VI's withdrawal of a substantial sum from the Bank of Brazil upon his departure effectively triggered a near-bankruptcy. Furthermore, recognition of Brazil's independence by England came at a cost of two million pounds. Moreover, the absence of a well-established tradition of higher-level art education and practice within the country limited artistic development. Even the local elites, by and large, exhibited a provincial outlook in artistic matters.[16][17][18][2]

The situation improved during the period of political stabilization known as the Second Reign. However, imperial patronage of the arts remained modest. The overall cultural environment became increasingly marked by a sense of fiscal restraint. In contrast to the opulence of European courts, Brazilian imperial residences resembled the grand homes of minor nobility. Even the crown for Pedro II's coronation was crafted using materials from his father's crown, reflecting the budgetary limitations. The Academy's annual expenditures, including scholarships, salaries, equipment and building maintenance, and pensions, did not surpass eight hundred and twenty million réis. This sum was comparable to the imperial family's summer expenses in Petrópolis and half the cost of maintaining the imperial stables. The domestic art market remained restricted throughout this period, with the imperial family serving as the primary patrons.[2][1]

The creation of a face for Brazil

Brazilian Romanticism reached its peak during a period when the movement in Europe had already entered its later stages, characterized by a shift towards catering to the tastes of the affluent and established middle class. This 'bourgeois' Romanticism had largely abandoned the earlier emphasis on egalitarianism inspired by the French Revolution and the robust energy associated with Napoleonic imperialism. It was the more conservative and sentimental iteration of Romanticism that primarily influenced the development of Brazilian Romantic painting. This artistic movement flourished almost exclusively within the confines of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro.[1][19]

Despite its structural similarities to the French Academy, the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro faced significant challenges, as it lacked a well-established tradition and operated with a precarious structure and limited resources. Furthermore, Brazilian society at large did not fully recognize the value of the Academy's educational project. Similarly, many aspiring artists, with a few notable exceptions, lacked the foundational education to fully benefit from the Academy's instruction. Documents from the period consistently highlight recurring difficulties, including a shortage of qualified instructors and equipment, along with the inadequate preparation of students, some of whom exhibited basic literacy deficiencies. The Academy's achievements were largely contingent upon the personal patronage of Emperor Pedro II. A strong advocate for the arts and sciences, he positioned the Academy as the artistic engine of his nationalist project.[1][19]

Despite its limitations, the Imperial Academy entered its most stable and productive period during the Second Reign. Under Emperor Pedro II's direct supervision, the Academy achieved a greater degree of operational stability. This period of improved resources provided fertile ground for the flourishing of Brazilian Romantic painting, fostering the emergence of prominent figures such as Victor Meirelles, Pedro Américo, Rodolfo Amoedo and Almeida Júnior. These artists built upon the foundational work of Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre, whose contributions were instrumental in developing a symbolic visual language capable of unifying the nationalist movement active during this period. Nationalist aspirations sought to establish Brazil's equivalence with the most "civilized" European states. Januário da Cunha Barbosa, secretary of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute, echoed this sentiment, arguing against foreigners shaping Brazil's historical narrative.[2][19][20]

The artistic program of the Imperial Academy operated within a well-defined ideological framework and prioritized specific themes. This approach differed from the earlier, more independent and passionate works created by the traveling artists of the early 19th century. Their works, primarily directed towards European scientific circles interested in natural history, did not establish a lasting artistic school in Brazil. Their influence, if any, seems to be limited to the international promotion of Brazil's natural beauty, which would later attract a greater number of artists who would have a more significant impact on the development of a distinct Brazilian artistic identity. The Academy's focus centered on portraiture, particularly of members of the new ruling house, and historical scenes depicting pivotal national events such as battles that secured Brazil's territorial integrity and sovereignty, the independence movement, and the role of indigenous people. Brazilian Romantic painting was characterized by a clear nationalistic sentiment, a didactic and progressive inclination, and a consistent idealism evident in the selection of themes and their expression. A notable shift occurred in the favored artistic techniques. The Davidian model of Neoclassical painting, emphasizing line over color, gave way to a greater emphasis on color and chiaroscuro (light and shadow). This change reflected a new sensibility, distinct from Neoclassicism, that was better suited to portraying Brazilian particularities. It is worth noting the divergence between Brazilian Romantic painting and literary Romanticism.The Academy, funded by the state, did not embrace the Byronic influence that pervaded Brazilian literature. Emperor Pedro II's nationalist project was inherently optimistic and fundamentally opposed to the ultra-sentimental and morbid characteristics of the second generation of Romantic writers, often referred to as the "bohemians" who grappled with the mal du siècle.[21][20]

While the Imperial Academy's emphasis on rigid aesthetic principles and its reliance on government approval did restrict the expression of artistic independence and originality, a hallmark of European Romanticism. Additionally, the movement lacked the contestatory and revolutionary spirit often associated with the early, more passionate phases of European Romanticism. However, attributing the restrained and conventional character of Brazilian Romantic painting solely to official constraints would be an oversimplification. As previously noted, the delayed emergence of Romanticism in Brazil meant it was primarily influenced by the waning stages of the movement in Europe, particularly French Pompier art, which is characterized by its bourgeois nature, emphasis on conformity, eclecticism, and sentimentality.[21][13]

Although a scholarship program offered travel to Europe for the most promising artists, such travel was intended to broaden their artistic horizons within certain parameters. Recommendations were made to avoid exposure to potentially disruptive influences, such as the works of Eugène Delacroix. His art, with its emphasis on individual liberty, could have conceivably cast doubt on the legitimacy of the newly established Brazilian government following its long period of dependence on Portugal. In this context, a notable characteristic of Brazilian Romanticism was a systematic disinclination to engage with Portuguese artistic traditions. Brazilian artists instead sought educational and inspirational models in France, and to a lesser extent, in Italy.[1]

Despite efforts to construct a national identity, Brazilian elites grappling with this process were not without blind spots regarding the pitfalls of emulating foreign models. Scholar Lilia Schwarcz argues that a paradox emerged in Brazil's attempt to develop its own visual iconography. On the one hand, Emperor Pedro II's nationalist project demonstrably possessed sincerity and arose from a clear need. However, his understanding of progress and civilization remained firmly rooted in European models. Consequently, the image of Brazil he sought to present to the world was inevitably selective, favoring portrayals of the landscape that adhered to European formal styles and overlooking negative social realities such as slavery. In Brazilian academic painting, with a few exceptions, the depiction of Black people largely remained confined to their role as anonymous figures within the landscape. Only with the growing momentum of the abolitionist movement and the subsequent republican era did Black figures begin to take center stage. It is important to note that by this point, Romanticism as an artistic movement was nearing its end, with new aesthetic schools gaining prominence.[22][2][1]

Indigenous people fared better in Brazilian Romantic art compared to Black portrayals. Following centuries of conflict and violence, the government now promoted their idealized depiction. These portrayals presented them as the embodiment of a pure culture living in harmony with their environment and positioned them as the other recognized ethnic group contributing to the formation of the new nation. This gave rise to the Indianist movement, a prominent channel for expressing Romantic ideals, finding even stronger resonance in literature and graphic arts. The emphasis on indigenous culture was reflected even in Dom Pedro II's regalia. His ceremonial mace incorporated toucan feathers, drawing inspiration from the featherwork of Indigenous leaders.[2][1]

Beyond the core thematic areas of historical scenes, landscapes, portraits of the imperial family, and depictions of Indigenous and working-class people, Brazilian Romantic painting encompassed a wider range of subjects. This included still lifes, genre scenes (everyday life), religious works, and even occasional forays into mythological allegories, Orientalist themes, and medievalism. These diverse subjects enriched the panorama of Brazilian Romantic art.[23][24] The influence of Romanticism and the academic model it championed persisted in Brazilian painting until the early 20th century, despite the emergence of new artistic movements such as Realism, Naturalism, Impressionism and Symbolism in the late 19th century. According to scholar Coelho de Sá, the final decades of the 19th century witnessed a "process of de-academization," where artistic instruction gradually departed from traditional methodologies. These methodologies had been centered on the study of the human figure, drawing techniques, and Renaissance illusionistic color palettes. This shift also involved a move away from the ideological, technical, and formal constraints of Romanticism.[23]

Central names

Araújo Porto-Alegre

Porto-Alegre was a polymorphous talent; diplomat, art critic, historian, architect, set designer, poet and writer, he left little work in painting, although he was the mentor of the next generation and perhaps the most typical of all the Romantics. His major importance was in organizing the academy, promoting nationalism, defending art as a relevant social force, and encouraging progress in general. The founding of the periodical Nitheroy in 1836 is regarded as one of the initial milestones of Brazilian Romanticism.[25] In a speech at the solemn session of the academy in 1855 he said:

The new classes, that the Imperial Government offers [...] today to the youth in this education reform, will open a new era for the Brazilian industry, and give the youth a secure subsistence. They will give artifice a new light, denied for thirty years by those who live off a part of their sweat; they will subtract another portion of the debt incurred in Ypiranga; because a nation is only independent when it exchanges the products of its intelligence, when it satisfies itself, or when it raises its national conscience, and leaves the tulmuthous arena, where internal and external contradictions are debated, to occupy itself with its material progress as the basis of its moral happiness. In these new classes he will have a fertile spring in all his future, a new view to study nature and admire its infinite variety and beauty. [...] Young people, leave the prejudice of longing for public jobs, the telethon of the offices, which ages you prematurely, and condemns you to poverty and to a continuous slavery; apply yourselves to arts and industry: the arm that was born to be an ass or a trowel should not handle the pen. Banish the prejudices of a decadent race, and the maxims of laziness and corruption: the artist, the artificer and the craftsman are as good workers in the building of the sublime nation as the priest, the magistrate and the soldier: work is strength, strength intelligence, and intelligence power and divinity.[26]

Pedro Américo

Pedro Américo, whose historical scene The Battle of Avaí, painted in Florence, catapulted him to fame in Europe and made him famous in Brazil even before it was exhibited to the public, generated a heated aesthetic and ideological debate that was fundamental in defining the directions of Brazilian art. He was also a rare case among his peers of intensive parallel cultivation of orientalism and religious painting, genres in which he declared to feel more comfortable, although they do not constitute his most relevant production for the history of national painting. But they are still an interesting document of the sentimentalism common to the later European Romantics, with whom he spent most of his career, far from Brazil.[27]

Victor Meirelles

Victor Meirelles, Pedro Americo's main competitor, was also the author of historical scenes emblematic of national identity, such as First Massa in Brazil, where he adopts Indianism and fuses his lyrical vein with his classicist and neo-Baroque inclinations, shaping one of Brazil's origin myths. According to Jorge Coli, "Meirelles achieved the rare convergence of forms, intentions, and meanings that make a painting enter powerfully into a culture. This image of the discovery will hardly ever be erased, or replaced. It is the first mass in Brazil. It is the powers of art fabricating history."[2]

Rodolfo Amoedo

Amoedo produced much on mythological and biblical themes, but in the early 1880s he was especially interested in Indianism,[28] producing at least one play of great significance in this trend, The last Tamoio, where he adds naturalistic elements in a rich and elegiac romantic representation. Later his work would assimilate the influence of Impressionism and touches of Orientalism, without, however, abandoning the dreamy and introspective atmospheres so dear to a certain strain of the Romantics. Gonzaga Duque says that his production reaches its peak with paintings such as Jacob's departure, The narration of Philéctas, and Bad News, where he formulates "an art finely expressive and less materialistic, in which exuded the dominant of his predilections embodied in a worldly refinement of existence or - to put it more succinctly - a certain elegant epicureanism, apprehended in the select coexistence of a cultured environment, of the super-ten, strongly shaken by sentimental crises, of atavistic background."[29]

Almeida Júnior

Almeida Júnior, the other great name of the period, after a clearly romantic beginning, where he left significant works, evolved quickly to the incorporation of Realism, with great interest in the popular types of the interior. He was the painter par excellence of the taste of the land, of the beauty of the landscape, of the Brazilian light, and this lasting Brazilianism is what most justifies his inclusion among the national romantics.[30]

Other artists

Other notable Brazilians also worked along romantic lines, at least part of their careers. Among them, Jerônimo José Telles Júnior, Aurélio de Figueiredo, Henrique Bernardelli, Antônio Parreiras, Antônio Firmino Monteiro, João Zeferino da Costa, Belmiro de Almeida, Eliseu Visconti, Arthur Timótheo da Costa, Pedro Weingärtner, and Décio Villares.[obsolete source]

In addition to the previously mentioned artist-explorers who played a pioneering role in Brazilian Romanticism, a significant number of foreign artists contributed to the movement during its peak and the Imperial Academy's operation. These artists, some of whom resided permanently in Brazil while others were transient, played a vital role in historical painting and landscape painting. They also served as instructors, disseminating artistic practices. Notable examples include landscape painters Henri Nicolas Vinet, Georg Grimm, and Nicola Antonio Facchinetti. Historical painters included Edoardo de Martino, Giovanni Battista Castagneto, José Maria de Medeiros, Pedro Peres, Louis-Auguste Moreaux, François-René Moreaux, and Augusto Rodrigues Duarte.[31][32] The landscape genre held particular appeal for foreign artists. Drawn to the exotic and picturesque qualities of Brazil's natural world, with its unfamiliar flora and fauna, they made significant contributions to the development of landscape painting in Brazil.[33]

Legacy

Similar to the ongoing debate among art critics regarding the precise definition and chronological boundaries of international Romanticism, the analysis of Brazilian 19th-century painting remains nuanced and subject to ongoing discussion.[34] Some scholars question the artistic merit of Brazilian Romantic painting and even hesitate to classify it as truly Romantic. They point to the presence of clear Neoclassical and realist elements, the influence of government control, and the deep entanglement with the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. This critical perspective dominated art historical discourse until the latter part of the 20th century. However, more recent scholarship conducted within a broader historical context acknowledges the presence of a well-defined Romantic style in Brazilian art, albeit confined to the realm of "academic Romanticism." This style played a significant role during its historical period.[1]

The late 19th century saw a rise in criticism against both the Imperial Academy and the Romantic movement. A younger generation of writers, including Gonzaga Duque and Angelo Agostini, targeted what they perceived as the weaknesses of Brazilian Romanticism. They criticized its utopian idealism as weak, elitist, and outdated. They further argued that it was subservient to European styles, irrelevant to national culture, and out of touch with contemporary trends. In their eagerness to see rapid artistic progress in Brazil, these critics lacked the necessary historical perspective to offer a balanced judgment. Their focus on the immediate context and their own surroundings limited their understanding of the historical forces that had shaped 19th-century Brazilian art. They also underestimated the challenges of fostering a large-scale cultural renewal in a nation still consolidating its independence. Furthermore, they overlooked the enduring influence of Brazil's Baroque heritage, which continued to manifest in various regional artistic expressions and popular culture, largely unaffected by developments in Rio de Janeiro.[35][36][37][38]

Despite ongoing critiques, Brazilian Romantic painting produced in the latter half of the 19th century can be viewed as a significant achievement. Emerging from a nascent artistic tradition, it marked a turning point and left a lasting impression on the nation's collective memory. This artistic movement is arguably symbolic of Brazil's entry into modernity. The public impact of works like Victor Meirelles' and Pedro Américo's depictions of historical battles was undeniable. Exhibited at the 1879 Salon, these paintings drew a remarkable audience exceeding 292,000 visitors over a 62-day period.This level of engagement remains unmatched even by contemporary events like the São Paulo Art Biennials, considering Rio de Janeiro's population of just over 300,000 at the time.[39] Brazil's first foray into the prestigious Paris Salon occurred with a Romantic work, "The First Mass in Brazil". Similarly, "The Battle of Avaí" marked the first instance of a Brazilian artist achieving international recognition, albeit modest, for their work. These developments represented initial steps towards Brazil's active participation in the global art scene. Many key Romantic paintings, including "Moema", "The Last Tamoio", "Independence or Death!", and "The Emperor's Speech", have become iconic visual representations of Brazilian history. Their enduring popularity is evidenced by their continued inclusion in school textbooks, reaching millions of students each year. This widespread exposure speaks to the artistic merit of these works, the effectiveness of the Romantic style in conveying historical narratives, and the foresight of the government's artistic project that fostered their creation. The Romantic movement's portrayal of Indigenous people in a more sympathetic light, along with its positive depictions of other working-class figures, can be seen as an early step towards greater national integration. Furthermore, the emphasis on nationalism within Romantic art arguably laid the groundwork for the modern conception of Brazilian identity.[27][2][1]

Gallery

-

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay: Tropeiros trading a horse. Imperial Museum of Brazil

-

Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre: Cave. National Museum of Fine Arts

-

Agostinho da Mota: View of Rio de Janeiro

-

Victor Meirelles: Moema, 1866. São Paulo Museum of Art

-

Almeida Júnior: Girl with a book, São Paulo Museum of Art

-

Augusto Rodrigues Duarte: Atala's funeral, 1878. National Museum of Fine Arts

-

Almeida Júnior: Flight of the Holy Family to Egypt, 1881. National Museum of Fine Arts

-