Brownian motion: Difference between revisions

300 is a better approximation than 280 |

+iw |

||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

[[ta:பிரௌனியன் இயக்கம்]] |

[[ta:பிரௌனியன் இயக்கம்]] |

||

[[tr:Brown hareketi]] |

[[tr:Brown hareketi]] |

||

[[uk:Броунівський рух]] |

|||

[[zh:布朗運動]] |

[[zh:布朗運動]] |

||

Revision as of 09:38, 21 June 2007

- This article is about the physical phenomenon; for the stochastic process, see Wiener process. For the sports team, see Brownian Motion (Ultimate).

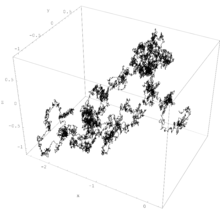

Brownian motion (named in honor of the botanist Robert Brown) is either the random movement of particles suspended in a fluid or the mathematical model used to describe such random movements, often called a Wiener process.

The mathematical model of Brownian motion has several real-world applications. An often quoted example is stock market fluctuations. Another example is the evolution of physical characteristics in the fossil record.[citation needed]

Brownian motion is among the simplest continuous-time stochastic processes, and it is a limit of both simpler and more complicated stochastic processes (see random walk and Donsker's theorem). This universality is closely related to the universality of the normal distribution. In both cases, it is often mathematical convenience rather than the accuracy of the models that motivates their use.

The concept has also been applied in the field of cultural studies. In Michel de Certeau's The Practice of Everyday Life, the concept of "Brownian motion" is used to describe the tactical maneuvers of the Other. In reference to the rise of a "cybernetic society," de Certeau suggests that this society will be "a scene of Brownian movements of invisible and innumerbable tactics" (PEL, 40). Building on de Certeau's theorizing, Constance Penley elaborates on the concept in "Brownian Motion: Women, Tactics and Technology" (an essay that appeared in Penley and Andrew Ross's Technoculture, 1991).

History

Jan Ingenhousz had observed the irregular motion of coal dust particles on the surface of alcohol in 1785 but Brownian motion is generally regarded as having been discovered by the botanist Robert Brown in 1827. It is believed that Brown was studying pollen particles floating in water under the microscope. He then observed minute particles within the vacuoles of the pollen grains executing a jittery motion. By repeating the experiment with particles of dust, he was able to rule out that the motion was due to pollen particles being 'alive', although the origin of the motion was yet to be explained.

The first person to describe the mathematics behind Brownian motion was Thorvald N. Thiele in 1880 in a paper on the method of least squares. This was followed independently by Louis Bachelier in 1900 in his PhD thesis "The theory of speculation." However, it was Albert Einstein's independent research of the problem in his 1905 paper that brought the solution to the attention of physicists, and presented it as a way to indirectly confirm the existence of atoms and molecules. (Bachelier's thesis presented a stochastic analysis of the stock and option markets.)

At that time the atomic nature of matter was still a controversial idea. Einstein and Marian Smoluchowski observed that, if the kinetic theory of fluids was right, then the molecules of water would move at random. Therefore, a small particle would receive a random number of impacts of random strength and from random directions in any short period of time. This random bombardment by the molecules of the fluid would cause a sufficiently small particle to move in exactly the way described by Brown. Theodor Svedberg made important demonstrations of Brownian motion in colloids and Felix Ehrenhaft, of particles of silver in air. Jean Perrin carried out experiments to test the new mathematical models, and his published results finally put an end to the two thousand year-old dispute about the reality of atoms and molecules.

Intuitive metaphor for Brownian motion

Consider a large balloon of 10 meters in diameter. Imagine this large balloon in a football stadium or any widely crowded area. The balloon is so large that it lies on top of many members of the crowd. Because they are excited, these fans hit the balloon at different times and in different directions with the motions being completely random. In the end, the balloon is pushed in random directions, so it should not move on average. Consider now the force exerted at a certain time. We might have 20 supporters pushing right, and 21 other supporters pushing left, where each supporter is exerting equivalent amounts of force. In this case, the forces exerted from the left side and the right side are imbalanced in favor of the left side; the balloon will move slightly to the left. This imbalance exists at all times, and it causes random motion. If we look at this situation from above, so that we cannot see the supporters, we see the large balloon as a small object animated by erratic movement.

Now return to Brown’s pollen particle swimming randomly in water. One molecule of water is about .1 to .2 nm, (a hydrogen-bonded cluster of 300 atoms has a diameter of approximately 3 nm) where the pollen particle is roughly 1 µm in diameter, roughly 10,000 times larger than a water molecule. So, the pollen particle can be considered as a very large balloon constantly being pushed by water molecules. The Brownian motion of particles in a liquid is due to the instantaneous imbalance in the force exerted by the small liquid molecules on the particle.

A Java applet animating this idea is available here.

Modelling the Brownian motion using differential equations

The equations governing Brownian motion relate slightly differently to each of the two definitions of Brownian motion given at the start of this article.

Mathematical Brownian motion

For a particle experiencing a brownian motion corresponding to the mathematical definition, the equation governing the time evolution of the probability density function associated to the position of the Brownian particle is the diffusion equation, a partial differential equation.

The time evolution of the position of the Brownian particle itself can be described approximately by Langevin equation, an equation which involves a random force field representing the effect of the thermal fluctuations of the solvent on the Brownian particle. On long timescales, the mathematical Brownian motion is well described by Langevin equation. On small timescales, Inertial effects are prevalent in Langevin equation. However the mathematical brownian motion is exempt of such inertial effects. Note that inertial effects have to be considered in Langevin equation, otherwise the equation becomes singular, so that simply removing the inertia term from this equation would not yield an exact description, but rather a singular behavior in which the particle doesn't move at all.

Physical Brownian motion

The diffusion equation yields an approximation of the time evolution of the probability density function associated to the position of the particle undergoing a Brownian movement under the physical definition. The approximation is valid on short timescales (see Langevin equation for details).

The time evolution of the position of the Brownian particle itself is best described using Langevin equation, an equation which involves a random force field representing the effect of the thermal fluctuations of the solvent on the particle.

The displacement of a particle undergoing Brownian motion is obtained by solving the diffusion equation under appropriate boundary conditions and finding the rms of the solution. This shows that the displacement varies as the square root of the time, not linearly. Hence why previous experimental results concerning the velocity of Brownian particles gave nonsensical results. A linear time dependence was incorrectly assumed.

Criticism of Einstein's Formulation

Recent research into the history of mathematics--especially Einstein's mathematical views--has caused some disquiet as to his formulation of Brownian motion.

“Einstein begins with an assumption whose status is still problematic and troubled his contemporaries: that there exists ‘a time interval τ, which shall be very small compared with observable time intervals but still so large that all motions performed by a particle during two consecutive time intervals τ may be considered as mutually independent events….” As the author of this passage notes, “[t]his is essentially a very strong Markov postulate. Einstein makes no attempt to justify it….[W]here mathematics ends and physics begins is far from clear….” Sahotra Sarkar, “Physical Approximations and Stochastic Processes in Einstein’s 1905 Paper on Brownian Motion,” in D. Howard and J. Stachel, eds., Einstein the Formative Years 1879-1900, Basel 2000. This, in turn, has led to a reexamination of the origins of natural mathematics, the mathematics in which Einstein expressed both Brownian motion and special relativity, especially the relativity of simultaneity. See A. Garciadiego, Bertrand Russell and the Origins of the Set-Theoretic 'Paradoxes,' 1992.

Popular culture

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (June 2007) |

In Douglas Adams's The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Brownian motion is used to create (or rather calculate) the Infinite Improbability Drive that powers the spaceship Heart of Gold. The Brownian motion generator is a cup of hot tea.

In Murray Leinster's short story, A Logic Named Joe, the logic (computer) suggests building a perpetual motion machine using Brownian motion.

In Julio Cortazar's novel Rayuela, Brownian motion is used to describe travelers in Paris at night.

See also

- Brownian bridge

- Brownian frontier

- Brownian motor

- Red noise, also known as brown noise (Martin Gardner proposed this name for sound generated with random intervals. It is a pun on Brownian motion and white noise.)

- Brownian ratchet

- Brownian tree

- Tyndall effect, Physical chemistry phenomenon where particles are involved; used to differentiate between the different types of mixtures.

- Diffusion equation

- Langevin equation

- Brownian dynamics

- Osmosis

- Ultramicroscope

- Local time (mathematics)

- Complex system

References

- Brown, Robert, "A brief account of microscopical observations made in the months of June, July and August, 1827, on the particles contained in the pollen of plants; and on the general existence of active molecules in organic and inorganic bodies." Phil. Mag. 4, 161-173, 1828. (PDF version of original paper including a subsequent defense by Brown of his original observations, Additional remarks on active molecules.)

- Einstein, A. "Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen." Ann. Phys. 17, 549, 1905. [1]

- Einstein, A. "Investigations on the Theory of Brownian Movement". New York: Dover, 1956. ISBN 0-486-60304-0 [2]

- Theile, T. N. Danish version: "Om Anvendelse af mindste Kvadraters Methode i nogle Tilfælde, hvor en Komplikation af visse Slags uensartede tilfældige Fejlkilder giver Fejlene en ‘systematisk’ Karakter". French version: "Sur la compensation de quelques erreurs quasi-systématiques par la méthodes de moindre carrés" published simultaneously in Vidensk. Selsk. Skr. 5. Rk., naturvid. og mat. Afd., 12:381–408, 1880.

- Nelson, Edward, Dynamical Theories of Brownian Motion (1967) (PDF version of this out-of-print book, from the author's webpage.)

- Ruben D. Cohen (1986) “Self Similarity in Brownian Motion and Other Ergodic Phenomena,” Journal of Chemical Education 63, pp. 933-934 [http://rdcohen.50megs.com/BrownianMotion.pdf download

- J. Perrin, Ann. Chem. Phys. 18, 1 (1909). See also book "Les Atomes" (1914).