Oxyhydrogen: Difference between revisions

SteveBaker (talk | contribs) |

Undid revision 222650915 by SteveBaker (talk) |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

The oxyhydrogen flame begins a short distance from the torch tip; if the distance is great enough the torch tip can remain relatively cool.<ref name="GW">{{citebook|title=Brown's Gas Book 2 |author= George Wiseman|publisher=Eagle Research |id=ISBN 1895882192 |pages=59|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=HBCbAQAACAAJ&dq=1895882192}}</ref> |

The oxyhydrogen flame begins a short distance from the torch tip; if the distance is great enough the torch tip can remain relatively cool.<ref name="GW">{{citebook|title=Brown's Gas Book 2 |author= George Wiseman|publisher=Eagle Research |id=ISBN 1895882192 |pages=59|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=HBCbAQAACAAJ&dq=1895882192}}</ref> |

||

==Production== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==Applications - Claimed== |

==Applications - Claimed== |

||

===Automotive=== |

===Automotive=== |

||

{{see also|water-fuelled car}} |

{{see also|water-fuelled car}} |

||

<!-- This is a DESCRIPTION of what people make and sell (facts about what are being MADE in light of the claims. These are not the claims specifically, (Which are said to be fraudulent later) but the actual APPLICATIONs and products -->With the rising cost of fuel, many people have experimented with using oxyhydrogen to supplement an engine's fuel in order to improve fuel efficiency. These devices typically use electricity produced by a vehicle's [[alternator]] to generate the energy needed to split water into hydrogen and oxygen gases. The oxyhydrogen that gets generated is piped into the engine's air intake, allowing the combustible gas to be ingested along with the air. Some of these devices are manufactured and sold as a complete kit, while many are made at home from published plans. <!-- It seems there are Wikipedians afraid to describe the devices at all or name them, since there is a controversy just saying what the claimed application is. If such devices exist in such a great measure and in such imitation of the devices that have been debunked, then briefly and accurately describing them is necessary before concluding that they are junk science. But the consensus seems to be to remove the description of the devices rather than properly debunk it.--> |

|||

Oxyhydrogen is often mentioned in conjunction with devices that claim to increase automotive engine efficiency or to operate a car using water as a fuel. |

|||

<!-- This is a scientific view of such devices and the claims which support the devices -->Some <!-- "Some" is not "all" -->manufacturers, publishers, and researchers make claims that violate the [[Laws of thermodynamics]]. See [[Conservation of energy]] and [[Electrolysis of water#Efficiency|Electrolysis of water:Efficiency]]. To date, none of these claims have been proven true by reputable sources<ref name="EPA testing">{{cite web |

|||

| url=http://www.epa.gov/otaq/consumer/reports.htm |

| url=http://www.epa.gov/otaq/consumer/reports.htm |

||

| title=List of devices tested under EPA Gas Saving and Emission Reduction Devices Evaluation |

| title=List of devices tested under EPA Gas Saving and Emission Reduction Devices Evaluation |

||

| Line 73: | Line 79: | ||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

== |

===Water torch=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

====Water torch==== |

|||

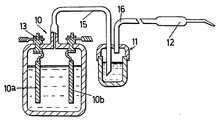

[[Image:Browns gas bubbler.png|thumb|right|A bubbler apparatus used to mitigate potential flashback.<ref name="US patent 4014777">{{US patent reference |

[[Image:Browns gas bubbler.png|thumb|right|A bubbler apparatus used to mitigate potential flashback.<ref name="US patent 4014777">{{US patent reference |

||

| number = 4014777 |

| number = 4014777 |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

}}</ref> Water torches must be designed to mitigate [[Flashback (welding)|flashback]] by strengthening the electrolytic chamber. Use of an intermediary water [[Oil bubbler|bubbler]] eliminates potential electrolyzer damage from flashback, with a dry [[flashback arrestor]] being ineffective due to flame velocity. The bubbler is connected directly in series with the output gas. A water bubbler is sometimes referred to as a wet flashback arrestor, and effectively captures any remaining [[electrolyte]] in the output gas. Suitable electrolytes include [[Sodium hydroxide|sodium]] or [[potassium hydroxide]], and other salts that ionize well.<ref name="GW"/> Also "the electrolyzer system must be of high enough pressure to keep the gas velocity at the nozzle above the combustion velocity of the flame, or the system will backfire".<ref name="GW"/> |

}}</ref> Water torches must be designed to mitigate [[Flashback (welding)|flashback]] by strengthening the electrolytic chamber. Use of an intermediary water [[Oil bubbler|bubbler]] eliminates potential electrolyzer damage from flashback, with a dry [[flashback arrestor]] being ineffective due to flame velocity. The bubbler is connected directly in series with the output gas. A water bubbler is sometimes referred to as a wet flashback arrestor, and effectively captures any remaining [[electrolyte]] in the output gas. Suitable electrolytes include [[Sodium hydroxide|sodium]] or [[potassium hydroxide]], and other salts that ionize well.<ref name="GW"/> Also "the electrolyzer system must be of high enough pressure to keep the gas velocity at the nozzle above the combustion velocity of the flame, or the system will backfire".<ref name="GW"/> |

||

===Brown's design=== |

|||

[[Image:Seriescellelectrolyzerdesign.png|thumb|right|The series cell design by Yull Brown.<ref name="US patent 4014777"/>]] |

[[Image:Seriescellelectrolyzerdesign.png|thumb|right|The series cell design by Yull Brown.<ref name="US patent 4014777"/>]] |

||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

| title = Arc-assisted oxy/hydrogen welding |

| title = Arc-assisted oxy/hydrogen welding |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

Brown's torches also used an electric arc to increase the temperature of the flame (called [[Atomic hydrogen welding|atomic welding]]) |

Brown's torches also used an electric arc to increase the temperature of the flame (called [[Atomic hydrogen welding|atomic welding]]).<ref name="US patent 4014777"/> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 21:30, 1 July 2008

Oxyhydrogen is a mixture of hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) gases, typically in a 2:1 molar ratio, the same proportion as water.[1] This gaseous mixture is used for torches for the processing of refractory materials.[citation needed]

Properties

Oxyhydrogen will combust when brought to its autoignition temperature. For a stoichiometric mixture at normal atmospheric pressure, autoignition occurs at about 570 °C (1065 °F).[2] The minimum energy required to ignite such a mixture with a spark is about 20 microjoules.[2] At normal temperature and pressure, oxyhydrogen can burn when it is between about 4% and 94% hydrogen by volume.[2]

When ignited, the gas mixture converts to water vapor and releases energy, which sustains the reaction: 241.8 kJ of energy (LHV) for every mole of Template:Hydrogen burned. The amount of heat energy released is independent of the mode of combustion, but the temperature of the flame varies.[1] The maximum temperature of about 2800 °C is achieved with a pure stoichiometric mixture, about 700 degrees hotter than a hydrogen flame in air.[3][4][5] When either of the gases are mixed in excess of this ratio, or when mixed with an inert gas like nitrogen, the heat must spread throughout a greater quantity of matter and the temperature will be lower.[1]

Applications - Historical

Lighting

Many forms of oxyhydrogen lamps have been described, such as the limelight, which used an oxyhydrogen flame to heat a piece of lime to white hot incandescence.[6] Because of the explosiveness of the oxyhydrogen, limelights have been replaced by electric lighting.

Oxyhydrogen has been used in working platinum[citation needed] because platinum could be melted (at a temperature of 1768.3 °C) only in an oxyhydrogen flame. These techniques have been superseded by the electric arc furnace.

Oxyhydrogen torch

An oxyhydrogen torch is an oxy-gas torch, which burns hydrogen (the fuel) with oxygen (the oxidizer). It is used for cutting and welding metals, glass, and thermoplastics.[6] An oxyhydrogen torch is used in the glass industry for "fire polishing"; slightly melting the surface of glass to remove scratches and dullness.[citation needed]

The oxyhydrogen flame begins a short distance from the torch tip; if the distance is great enough the torch tip can remain relatively cool.[7]

Production

A pure stoichiometric mixture is most easily obtained by water electrolysis, which uses an electric current to dissociate the water molecules:

- electrolysis: 2 H2O → 2 H2 + O2

- combustion: 2 H2 + O2 → 2 H2O

The energy required to generate the oxyhydrogen always exceeds the energy released by combusting it. (See Electrolysis of water:Efficiency).

Applications - Claimed

Automotive

With the rising cost of fuel, many people have experimented with using oxyhydrogen to supplement an engine's fuel in order to improve fuel efficiency. These devices typically use electricity produced by a vehicle's alternator to generate the energy needed to split water into hydrogen and oxygen gases. The oxyhydrogen that gets generated is piped into the engine's air intake, allowing the combustible gas to be ingested along with the air. Some of these devices are manufactured and sold as a complete kit, while many are made at home from published plans.

Some manufacturers, publishers, and researchers make claims that violate the Laws of thermodynamics. See Conservation of energy and Electrolysis of water:Efficiency. To date, none of these claims have been proven true by reputable sources[8], and many have been shown to be fraudulent.[9][10]

Water torch

A water torch is a kind of oxyhydrogen torch, that is fed by oxygen and hydrogen generated on demand by water electrolysis. The device avoids the need for bottled oxygen and hydrogen, and requires electricity. Some models of water torches mix the two gases immediately after production (vs. the torch tip) making the gas mixture more accurate.[11] This electrolyzer design is referred to as "common-ducted",[7] and the first was invented by William A. Rhodes in 1966.[12] Water torches must be designed to mitigate flashback by strengthening the electrolytic chamber. Use of an intermediary water bubbler eliminates potential electrolyzer damage from flashback, with a dry flashback arrestor being ineffective due to flame velocity. The bubbler is connected directly in series with the output gas. A water bubbler is sometimes referred to as a wet flashback arrestor, and effectively captures any remaining electrolyte in the output gas. Suitable electrolytes include sodium or potassium hydroxide, and other salts that ionize well.[7] Also "the electrolyzer system must be of high enough pressure to keep the gas velocity at the nozzle above the combustion velocity of the flame, or the system will backfire".[7]

Brown's design

Oxyhydrogen gas produced in a common-ducted electrolyzer has been referred to as "Brown's gas",[citation needed] after Yull Brown who received a utility patent for a series cell common-ducted electrolyzer in 1977 and 1978 (the term "Brown's gas" is not used in his patents, but "a mixture of oxygen and hydrogen" is referenced).[11][13] Brown's torches also used an electric arc to increase the temperature of the flame (called atomic welding).[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b c 1911 Encyclopedia. "Oxyhydrogen Flame". (Available here Accessed 2008-01-19.)

- ^ a b c O'Connor, Ken. "Hydrogen". NASA Glenn Research Center Glenn Safety Manual.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Calvert, Dr. James B. (2006-09-09). "Hydrogen". University of Denver faculty page. Retrieved 2008-04-05. "An air-hydrogen torch flame reaches 2045 °C, while an oxyhydrogen flame reaches 2660 °C."

- ^ "Adiabatic Flame Temperature". The Engineering Toolbox. Retrieved 2008-04-05. "Oxygen as Oxidizer: 3079 K, Air as Oxidizer: 2384 K"

- ^ "Temperature of a Blue Flame". Retrieved 2008-04-05. "Hydrogen in air: 2,400 K, Hydrogen in Oxygen: 3,080 K"

- ^ a b William Augustus Tilden. Chemical Discovery and Invention in the Twentieth Century. Adamant Media Corporation. p. 80. ISBN 0543916464.

- ^ a b c d George Wiseman. Brown's Gas Book 2. Eagle Research. p. 59. ISBN 1895882192.

- ^ "List of devices tested under EPA Gas Saving and Emission Reduction Devices Evaluation". Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Edwards, Tony (1996-12-01). "End of road for car that ran on Water". The Sunday Times. Times Newspapers Limited. p. Features 12. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ "Fuel Injected Lunatic - Inventor Paul Pantone hoped to save the world. Now, will the world save him?". Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b c d e US patent 4014777, Yull Brown, "Welding", issued 1977-03-29

- ^ US patent 3262872, William Rhodes, "Generator Patent", issued 1966-07-26

- ^ US patent 4081656, Yull Brown, "Arc-assisted oxy/hydrogen welding", issued 1978-03-28

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)