Pig War (1859): Difference between revisions

fix incomplete reversion of vandalism |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

The Pig War is commemorated in [[San Juan Island National Historical Park]].<ref name="Woodbury"/> |

The Pig War is commemorated in [[San Juan Island National Historical Park]].<ref name="Woodbury"/> |

||

==Books== |

|||

* Coleman, E.C., ''The Pig War'', [[The History Press]] 2009 |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 11:19, 31 March 2009

| Pig War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

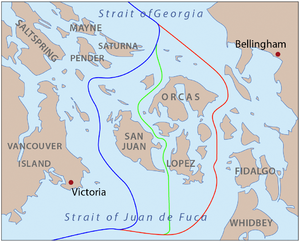

Proposed boundaries: Through Haro Strait, favored by the US

Through Rosario Strait, favored by Britain

Through San Juan Channel, compromise proposal

The curved lines are as shown on maps of the time. The modern boundary is made of straight line segments and roughly follows the blue line. | |||||||

| |||||||

The Pig War was a confrontation in 1859 between American and British authorities over the boundary between the United States and British North America. The specific area in dispute was the San Juan Islands, which lie between Vancouver Island and the North American mainland. The Pig War, so called because it was triggered by the shooting of a pig, is also called the Pig Episode, the Pig and Potato War, the San Juan Boundary Dispute or the Northwestern Boundary Dispute. The pig was the only "casualty" of the war, making the conflict essentially bloodless.

Background

The Oregon Treaty of June 15, 1846 resolved the Oregon boundary dispute by dividing the Oregon Country/Columbia District between the United States and Britain "along the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver Island, and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of Juan de Fuca Strait, to the Pacific Ocean.[1]"

However, there are actually two straits which could be called the middle of the channel: Haro Strait, along the west side of the San Juan Islands; and Rosario Strait, along the east side.[2]

In 1846 there was still some uncertainty about the geography of the region. The most commonly available maps were those of George Vancouver, published in 1798, and of Charles Wilkes, published in 1845. In both cases the maps are unclear in the vicinity of the southeastern coast of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. As a result, Haro Strait is not fully clear either.[3]

In 1856 the US and Britain set up a Boundary Commission to survey the international boundary. Since the boundary around the San Juans had not been resolved the commissioners made proposals and counter-proposals. There were three main proposals considered, Haro Strait, Rosario Strait, and a compromise line running through San Juan Channel. The extreme US proposal was "in accordance with the strict letter of the treaty", and ran between Vancouver Island and all islands off its coast, including the San Juans and Gulf Islands. This line was never seriously considered. The British commissioners made their case in part by referring to maps made by Americans that showed the boundary running through Rosario Strait. Among such maps was one by highly regarded American geographer John C. Frémont. Nevertheless, the commissioners could not reach an agreement.[3]

Because of this ambiguity, both the United States and Britain claimed sovereignty over the San Juan Islands.[4] During this period of disputed sovereignty, Britain's Hudson's Bay Company established operations on San Juan and turned the island into a sheep ranch. Meanwhile by mid-1859, twenty-five to twenty-nine American settlers had arrived.[2][5]

The pig

On June 15, 1859, exactly thirteen years after the adoption of the Oregon Treaty, the ambiguity led to direct conflict. Lyman Cutlar, an American farmer who had moved onto the island claiming rights to live there under the United States' Donation Land Claim Act (1850), shot and killed a pig rooting in his garden.[2][4][6] He had found the giant black boar eating his tubers while a man stood next to the fence laughing. Cutlar was so upset that he took aim and shot the pig. The mysterious man then ran away into the woods. It turns out that the pig was owned by an Irishman, Charles Griffin, who was employed by the Hudson's Bay Company to run the sheep ranch.[2][4][6] He also owned several pigs which he allowed to roam freely. The two had lived in peace until this incident. Cutlar offered $10 to Griffin to compensate for the pig, but Griffin was unsatisfied with this offer and demanded $100. Following this reply, Cutlar believed he shouldn't have to pay for the pig because the pig had been trespassing on his land. (A possibly apocryphal story claims Cutlar said to Griffin, "It was eating my potatoes." Griffin replied, "It is up to you to keep your potatoes out of my pig."[6]) When British authorities threatened to arrest Cutlar, American settlers called for military protection.

Military escalation

William S. Harney, commanding the Dept. of Oregon, initially dispatched 66 American soldiers of the 9th Infantry under the command of Captain George Pickett to San Juan Island with orders to prevent the British from landing.[2][4] Concerned that a squatter population of Americans would begin to occupy San Juan Island if the Americans were not kept in check, the British sent three British warships under the command of Captain Geoffrey Hornby to counter the Americans.[2][4][6] The situation continued to escalate. By August 10, 1859, 461 Americans with 14 cannons under Colonel Silas Casey were opposed by five British warships mounting 70 guns and carrying 2,140 men.[2][4][6] During this time, no shots were fired.

The governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, James Douglas, ordered British Rear Admiral Robert L. Baynes to land marines on San Juan Island and engage the American soldiers under the command of Brigadier-General William Selby Harney. (Harney's forces had occupied the island since July 27, 1859.) Baynes refused, deciding that "two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig" was foolish.[4][6] Local commanding officers on both sides had been given essentially the same orders: defend yourselves, but absolutely do not fire the first shot. For several days, the British and U.S. soldiers exchanged insults, each side attempting to goad the others into firing the first shot, but discipline held on both sides, and thus no shots were fired.

Resolution

In September, U.S. President James Buchanan sent General Winfield Scott to negotiate with Governor Douglas to resolve the growing crisis.[4][6] This was in the best interest of the United States, as sectional tensions within the country were increasing, culminating in the Civil War.[6] As a result of the negotiations, both sides agreed to retain joint military occupation of the island, reducing their presence to a token force of no more than 100 men.[4] The "British Camp" was established on the north end of San Juan Island along the shoreline, for ease of supply and access; and the "American Camp" was created on the south end on a high, windswept meadow, suitable for artillery barrages against shipping.[6] (Today the Union Jack still flies above the "British Camp", being raised and lowered daily by park rangers, making it one of the very few places without diplomatic status where US government employees regularly hoist the flag of another country.)

During the years of joint military occupation, the small British and American units on San Juan Island had a very amicable mutual social life, visiting one another's camps to celebrate their respective national holidays and holding various athletic competitions. Park rangers tell visitors the biggest threat to peace on the island during these years was "the large amounts of alcohol available."

This state of affairs continued for the next 12 years, when the matter was referred to Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany. On October 21, 1872, a commission appointed by the Kaiser decided in favor of the United States claim to the San Juan Islands.[4][2][6]

On November 25, 1872, the British withdrew their Royal Marines from the British Camp.[2] The Americans followed by July 1874.[4][2]

The Pig War is commemorated in San Juan Island National Historical Park.[6]

Books

- Coleman, E.C., The Pig War, The History Press 2009

See also

- Aroostook War, the "Northeastern Boundary Dispute"

- List of conflicts in the United States

- List of conflicts in Canada

- Military history of Canada

- Military history of the United Kingdom

- Military history of the United States

- Point Roberts

References

- ^ Oregon Treaty from Wikisource. Visited October 16, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Matthews, Todd. "The Pig War Of San Juan Island", The Tablet.

- ^ a b Hayes, Derek (1999). Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of exploration and Discovery. Sasquatch Books. pp. 171–174. ISBN 1-57061-215-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "The Pig War". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ^ British Columbia: From the earliest times to the present, Vol II by E.O.S. Scholefield and F.W. Howay

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Woodbury, Chuck (2000). "How One Pig Could Have Changed American History". Out West #15. Out West Newspaper. Retrieved 2006-10-16.