Colfax massacre: Difference between revisions

Adding citations |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

In August 1874, for instance, the White League pushed officeholders out in [[Coushatta, Louisiana|Coushatta]], [[Red River Parish]], assassinating the six white Republicans before they managed to leave, and killing five freedmen as witnesses. Four of the white men killed were related to the state representative from the area.<ref>Eric Foner,''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution'', New York: Perennial Classics, 2002, p. 551</ref> Such violence served to intimidate voters and officeholders. It was one of the methods white Democrats used to gain control in the 1876 elections and ultimately to dismantle Reconstruction in Louisiana. |

In August 1874, for instance, the White League pushed officeholders out in [[Coushatta, Louisiana|Coushatta]], [[Red River Parish]], assassinating the six white Republicans before they managed to leave, and killing five freedmen as witnesses. Four of the white men killed were related to the state representative from the area.<ref>Eric Foner,''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution'', New York: Perennial Classics, 2002, p. 551</ref> Such violence served to intimidate voters and officeholders. It was one of the methods white Democrats used to gain control in the 1876 elections and ultimately to dismantle Reconstruction in Louisiana. |

||

In 1950 Louisiana erected a state highway marker noting the event as the Colfax Riot, as it was called in the white community. It states, "On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of [[Carpetbagger|carpetbag]] misrule in [[Southern United States|the South]]."{{ |

In 1950 Louisiana erected a state highway marker noting the event as the Colfax Riot, as it was called in the white community. It states, "On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of [[Carpetbagger|carpetbag]] misrule in [[Southern United States|the South]]."<ref>{{cite book |

||

| last = Keith |

|||

| first = LeeAnna |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| publisher = Oxford University Press |

|||

| date = 2007 |

|||

| location = New York |

|||

| pages = 169 |

|||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=zEkQqruhR-sC&pg=PA169&lpg=PA169&dq=louisiana+highway+marker+colfax&source=bl&ots=oRVLknnfgc&sig=i0tu77j2fcQ8sgC945eZyqvWt7w&hl=en&ei=se4_Sri3JcrQlAeToOXADg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3 |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| isbn = 9780195310269}}</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Rubin |

|||

| first = Richard |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title = The Colfax Riot |

|||

| journal = The Atlantic Monthly |

|||

| volume = |

|||

| issue = July/August 2003 |

|||

| pages = |

|||

| publisher = The Atlantic Monthly |

|||

| location = |

|||

| date = July/August 2003 |

|||

| url = http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/2003/07/rubin.htm |

|||

| issn = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = June 2009}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The Colfax Riot is among the events of Reconstruction and late 19th century history which has received new national attention, much as the [[Rosewood massacre|1923 riot]] in [[Rosewood, Florida]] did near the end of the 20th century. In 2007 and 2008 two new books (see below) were published about the Colfax events, one especially addressing the implications of the Supreme Court case that arose out of prosecution of several men of the white militia. In addition, a documentary is in preparation. |

The Colfax Riot is among the events of Reconstruction and late 19th century history which has received new national attention, much as the [[Rosewood massacre|1923 riot]] in [[Rosewood, Florida]] did near the end of the 20th century. In 2007 and 2008 two new books (see below) were published about the Colfax events, one especially addressing the implications of the Supreme Court case that arose out of prosecution of several men of the white militia. In addition, a documentary is in preparation. |

||

| Line 68: | Line 100: | ||

* Goldman, Robert M., ''Reconstruction & Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank'', Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001. |

* Goldman, Robert M., ''Reconstruction & Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank'', Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001. |

||

* Hogue, James K., ''Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battle and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction'', Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006. |

* Hogue, James K., ''Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battle and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction'', Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* ''KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693. |

* ''KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693. |

||

* [[Charles Lane (journalist)|Lane, Charles]], ''The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction'', New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008. |

* [[Charles Lane (journalist)|Lane, Charles]], ''The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction'', New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008. |

||

Revision as of 21:04, 22 June 2009

The Colfax Massacre or Colfax Riot (as the events are termed on the official state historic marker) occurred on April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the seat of Grant Parish.

In the wake of a contested election for Governor and local offices, whites armed with rifles and a small cannon overpowered freedmen and state militia (also black) trying to control the parish courthouse.[1] [2] White Republican officeholders were not attacked. Most of the freedmen were killed after they surrendered, and nearly 50 were killed later that night after being held as prisoners for several hours. Estimates of the number of dead varied. A military report to Congress in 1875 identified the deaths of three white men and 105 black men by name, and also noted that 15-20 bodies of unidentified black men were recovered from the Red River. [3] A state historical marker from 1950 noted fatalities as three whites and 150 blacks.

The attack was the most violent example of turmoil following the disputed contest in 1872 between Republicans and Democrats for the Louisiana Governor's office, in which both candidates claimed victory. Although the Fusionist-dominated state "returning board", which ruled on validity of votes, at first declared John McEnery and his slate (Democrats) the winners, the board split and a pro-Kellogg faction declared Republican William P. Kellogg the victor. Both men held inauguration parties. A Republican federal judge in New Orleans ordered the Republican-majority legislature to be seated.[4]

The background of the situation was the struggle for power in the postwar environment, with a growing insurgency in the state. In Louisiana "every election between 1868 and 1876 was marked by rampant violence and pervasive fraud." [5] White Democrats worked to regain power, officially or unofficially.

Federal prosecution and conviction of a few perpetrators at Colfax under the Enforcement Act led to a key Supreme Court case, United States v. Cruikshank. In this 1876 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that protections of the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to the actions of individuals, but only to the actions of state governments. Thus, the Federal government could no longer use the Enforcement Act of 1870 to prosecute actions by paramilitary groups such as rifle clubs or the White League, which had chapters forming across Louisiana beginning in 1874.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, there has been increasing attention given to the events at Colfax and the Supreme Court case, and their meaning in U.S. history.

Background

In the wake of four years of Reconstruction-era Republican rule in Louisiana, the results of the November 1872 Louisiana elections were disputed. Both Democrats and Republicans claimed victory in the election for governor. During the last weeks of his term, Governor Henry C. Warmoth recognized the Conservative Democrat candidate for governor, John McEnery, as the victor against Republican Senator William P. Kellogg. Warmoth was subsequently impeached by the state legislature in a bribery scandal stemming from his actions in the 1872 election.

In the Colfax area Christopher Columbus Nash, a Confederate veteran, ran for Grant Parish sheriff as a Fusionist, supported by Democrats. Alphonse Cazabat, Nash's attorney, ran for local judge. The Republican candidates were R.C. Register (African American) for judge and Daniel Shaw (white) for sheriff.

Grant Parish was one of a number of new parishes created by the Republican government in an effort to build local support. Both the land and its people were originally tied to the Calhoun family, whose plantation had covered more than the borders of the parish. The freedmen had been slaves on the plantation. The parish also took in less developed hill country, with a population that had a narrow majority of 2400 freedmen, who mostly voted Republican, and 2200 whites, mostly Democrats. Statewide political tensions were reflected in the rumors going around each community, often about fears of attacks or outrages, adding to local tensions.[6]

While returns for the election for governor were being reviewed, the rival claimants Democrat McEnery and Republican Kellogg certified the candidates from each of their own parties for the sheriff and judge positions in Colfax/Grant Parish. Democrat McEnery certified his slate in December 1872, before the scheduled inauguration. Unrest and confusion were widespread; both governors held inaugural balls. Unrest was so marked that McEnery organized his own militia and in March attempted to take control of police stations in New Orleans, where the state government was then located, but was defeated.[5]

With support from the Federal government, Republican William Kellogg was certified and assumed control as Louisiana governor. In late March, Republicans Register and Shaw occupied their offices in the Colfax courthouse. Fearful that the Democrats might try to take over the local parish government, freedmen in Colfax started to create trenches around the courthouse and drilled to keep alert. They held the town for three weeks.[citation needed]

Local whites began to mobilize around rumors that local blacks had initiated a "reign of terror" and were roaming the countryside with the intent to "exterminate" all white people they found. Rumors and political tensions, as usual, were expressed with a sexual subtext. Accounts of the time said that whites believed rumors of alleged threats by freedmen's claiming they would seek revenge and take local white women for wives (or worse).[citation needed]

Economic factors (such as the building up of the largest State debt in the South, by the Republican administration) may have had more influence over attitudes than lurid sexual stories.

During the first days of April, stories began to spread in the black community of whites marching towards Colfax and harassing blacks in the surrounding countryside. White militias were gathering a few miles outside the settlement. After unknown whites murdered a freedman in the area on April 5, many local black citizens went to the Colfax courthouse for safety. As militia captain, Wiliam Ward, a veteran of the US Colored Troops, mustered his company in Colfax and took them to the courthouse. His state militia members were black.[6]

Riot or massacre

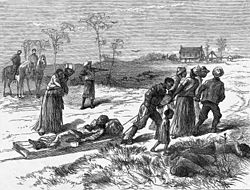

While armed white men had been gathering for days, with militia companies and veteran officers from Rapides, Winn and Catahoula parishes, Nash did not move his forces toward the courthouse until noon on Easter Sunday, April 13. Nash, a Democrat who was elected sheriff on the Fusionist ticket, led more than 300 armed white men, most on horseback and armed with rifles. Nash reportedly ordered those occupying the courthouse to leave. When that failed, Nash gave women and children camped outside the courthouse thirty minutes to clear out. After they left, the shooting began. The fighting continued for several hours with few casualties. Nash's militia maneuvered a cannon behind the building, which put more pressure on the defenders and caused some to panic.

About 60 defenders ran into nearby woods and jumped into the river. Nash sent men on horseback after the fleeing black Republicans and his militia killed most of them on the spot. Later on, Nash's besiegers directed a black captive to set the courthouse roof on fire. The defenders then displayed white flags for surrender: one made from a shirt, the other from a page of a book. The shooting stopped.

Nash's group approached and called for those surrendering to throw down their weapons and come outside. What happened next is in dispute. According to the reports of some whites, James Hadnot, also on the Fusionist ticket, was shot and wounded by someone from the courthouse. "In the Negro version, the men in the courthouse were stacking their guns when the white men approached, and Hadnot was shot from behind by an overexcited member of his own force." Hadnot died later, after being moved that night to be taken downstream by a passing steamboat.[7]

In the aftermath of Hadnot's shooting, the white militia reacted with mass killing. More than 40 times as many blacks died as did whites. The militia killed unarmed men trying to hide in the courthouse. They rode down those attempting to flee and killed them on the spot. They dumped some bodies in the Red River. About 50 blacks survived the afternoon and were taken prisoner. The prisoners were told they were going to be taken to a local jail, but later that night they were killed by their captors. Only one man of the group, Benjamin Brimm, survived. He was shot but managed to crawl away unnoticed. He later served as one of the Federal government's chief witnesses against those who were indicted for the attacks.[8]

On April 14 some of Governor Kellogg's new police force arrived from New Orleans. Several days later, two companies of Federal troops arrived. They searched for militia members, but many had already fled to Texas or the hills. The officers filed a military report in which they identified by name three whites and 105 blacks who had died, plus noted they had recovered 15-20 unidentified blacks from the river.[3] The exact number of dead was never established.

The bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era, the Colfax massacre taught many lessons, including the lengths to which some opponents of Reconstruction would go to regain their accustomed authority. Among blacks in Louisiana, the incident was long remembered as proof that in any large confrontation, they stood at a fatal disadvantage. "The organization against them is too strong. ..." Louisiana black teacher and Reconstruction legislator John G. Lewis later remarked. "They attempted [armed self-defense] in Colfax. The result was that on Easter Sunday of 1873, when the sun went down that night, it went down on the corpses of two hundred and eighty negroes."[1]

Aftermath

J.R. Beckwith, the US Attorney based in New Orleans, sent an urgent telegram about the massacre to the US Attorney General. The massacre in Colfax gained headlines from national newspapers from Boston to Chicago.[9] Various government forces spent weeks trying to round up members of the white militias. A total of 97 men were indicted. In the end, Beckwith charged nine men and brought them to trial for violations of the US Enforcement Act of 1870. It had been designed to provide Federal protection for civil rights of African Americans under the 14th Amendment against actions by terrorist groups such as the KKK.

The men were charged with one murder, and charges related to conspiracy against the rights of freedmen. There were two succeeding trials in 1874; in the first, one man was acquitted, while a mistrial was declared in the cases of the other eight. In the next trial, three men were found guilty of conspiracy against the freedmen's right of assembly and 15 other charges. Justice Joseph Bradley, an associate justice of the US Supreme Court happened to attend the trial. After the verdict was in, he ruled that the Enforcement Act was unconstitutional and had all the men set free.[10]

When the Federal government appealed the case, it was heard by the US Supreme Court as United States v. Cruikshank (1875). The Supreme Court ruled that the Enforcement Act of 1870 (which was based on the Bill of Rights and 14th Amendment) applied only to actions committed by the state, and that it did not apply to actions committed by individuals or private conspiracies. This meant that the Federal government could not prosecute such cases. The court said plaintiffs who believed their rights abridged had to seek protection from the state. Louisiana did not prosecute any of the perpetrators of the Colfax massacre.

With the publicity about the Colfax massacre and this ruling, there was a flourishing of white paramilitary organizations. In May 1874 Nash formed the White League from his militia, and chapters soon formed in other areas of Louisiana, as well as the southern parts of nearby states. Other paramilitary groups such as rifle clubs and Red Shirts also arose, especially in South Carolina and Mississippi, which also had black majorities of population. There was little recourse for black American citizens in the South. Paramilitary groups used violence and murder to terrorize leaders among the freedmen and white Republicans, as well as to repress voting among freedmen during the 1870s.

In August 1874, for instance, the White League pushed officeholders out in Coushatta, Red River Parish, assassinating the six white Republicans before they managed to leave, and killing five freedmen as witnesses. Four of the white men killed were related to the state representative from the area.[11] Such violence served to intimidate voters and officeholders. It was one of the methods white Democrats used to gain control in the 1876 elections and ultimately to dismantle Reconstruction in Louisiana.

In 1950 Louisiana erected a state highway marker noting the event as the Colfax Riot, as it was called in the white community. It states, "On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South."[12] [13]

The Colfax Riot is among the events of Reconstruction and late 19th century history which has received new national attention, much as the 1923 riot in Rosewood, Florida did near the end of the 20th century. In 2007 and 2008 two new books (see below) were published about the Colfax events, one especially addressing the implications of the Supreme Court case that arose out of prosecution of several men of the white militia. In addition, a documentary is in preparation.

In 2007 the Red River Heritage Association, Inc. was formed, a group that intends to establish a museum in Colfax as a center for collecting materials and interpreting the history of Reconstruction in Louisiana and especially the Red River area. In 2008, on the 135th anniversary of the Colfax Riot, there was an interracial ceremony to commemorate the event. The group lay flowers where some victims had fallen.[14]

Notes

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p.437

- ^ Ulysses S. Grant, People and Events: "The Colfax Massacre", PBS Website, accessed 6 Apr 2008

- ^ a b "Military Report on Colfax Riot, 1875", from the Congressional Record, accessed 6 Apr 2008

- ^ /Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died, New York: Macmillan, 2009, p.13

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, New York: Perennial Library edition, 1989, p.550

- ^ a b James K. Hogue, "The Battle of Colfax: Paramilitarism and Counterrevolution in Louisiana", 2006, accessed 15 Aug 2008

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar Strauss & Giroux, paperback, 2007, p.18

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar Strauss & Giroux, paperback, 2007, p.18-20

- ^ Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2008, p.22

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York; Farrar Strauss & Giroux, 2006, p.25

- ^ Eric Foner,Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, New York: Perennial Classics, 2002, p. 551

- ^ Keith, LeeAnna (2007). The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780195310269.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rubin, Richard (July/August 2003). "The Colfax Riot". The Atlantic Monthly (July/August 2003). The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved June 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ LeeAnna Keith, "History is a Gift: The Colfax Massacre", 17 Apr 2008, accessed 13 Aug 2008

References

- Foner, Eric, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, 1st ed., New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Goldman, Robert M., Reconstruction & Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

- Hogue, James K., Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battle and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

- KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693.

- Lane, Charles, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008.

- Lemann, Nicholas, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Rubin, Richard, "The Colfax Riot", The Atlantic, Jul/Aug 2003

- Taylor, Joe G., Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974, pp. 268–70.