American mutilation of Japanese war dead: Difference between revisions

→Dehumanization: edited for POV |

|||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

</ref> Japanese soldiers were taught to think of all prisoners as not worthy of consideration.<ref>Barak Kushner, ''The Thought War'', 2006, p. 131, Haruko Taya Cook & Theodore F. Cook, ''Japan at War'' 1993, p. 153,</ref> |

</ref> Japanese soldiers were taught to think of all prisoners as not worthy of consideration.<ref>Barak Kushner, ''The Thought War'', 2006, p. 131, Haruko Taya Cook & Theodore F. Cook, ''Japan at War'' 1993, p. 153,</ref> |

||

There was also popular anger in U.S. at the Japanese [[Attack on Pearl Harbor|surprise attack on Pearl Harbor]] amplifying pre-war racial prejudices.<ref name="Ferguson546" /> The U.S. media helped propagate this view of the Japanese, for example describing them as “yellow vermin”.<ref name=Weingartner54 />. In an official U.S. Navy film Japanese troops were described as “living, snarling rats”.<ref>Weingartner, p.54. Japanese were alternatively described and depicted as “mad dogs”, “yellow vermin”, termites, apes, monkeys, insects, reptiles and bats etc.</ref> The mixture of racism, [[propaganda]], and well- |

There was also popular anger in U.S. at the Japanese [[Attack on Pearl Harbor|surprise attack on Pearl Harbor]] amplifying pre-war racial prejudices.<ref name="Ferguson546" /> The U.S. media helped propagate this view of the Japanese, for example describing them as “yellow vermin”.<ref name=Weingartner54 />. In an official U.S. Navy film Japanese troops were described as “living, snarling rats”.<ref>Weingartner, p.54. Japanese were alternatively described and depicted as “mad dogs”, “yellow vermin”, termites, apes, monkeys, insects, reptiles and bats etc.</ref> The mixture of racism, [[propaganda]], and well-publicized [[Japanese war crimes|Japanese atrocities]] such as forced labor,<ref>[http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/links.html links for research, Allied POWs under the Japanese]</ref> [[cannibalism]],<ref>Tanaka, ''Hidden horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II'', Westview press, 1996, p.127.</ref> [[vivisection]],<ref>see [[unit 731]] or BBC [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/6185442.stm "Japanese doctor admits POW abuse"], [http://www.house.gov/bordallo/gwcrc/RL30606.pdf ''The Denver Post'', June 1, 1995, cited by Gary K. Reynolds, 2002, "U.S. Prisoners of War and Civilian American Citizens Captured and Interned by Japan in World War II: The Issue of Compensation by Japan" (Library of Congress) ]</ref> and torture of POW's,<ref>{{cite book |

||

|last=de Jong |

|last=de Jong |

||

|first=Louis |

|first=Louis |

||

Revision as of 18:25, 16 March 2010

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (June 2008) |

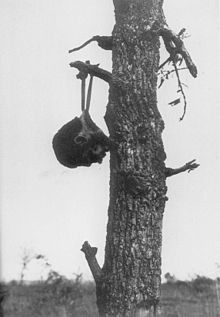

During World War II, some United States military personnel mutilated dead Japanese service personnel in the Pacific theater of operations. The mutilation of Japanese service personnel included the taking of body parts as “war souvenirs” and “war trophies”. Teeth were the most commonly taken objects, but skulls and other body parts were sometimes also collected. This behaviour was officially prohibited by the U.S. Military, but the prohibitions against it were not always enforced by officers in the field. It is not clear how common these behaviors were, nor have its causes been authoritatively determined.

Trophy taking

Only a minority of US troops collected Japanese body parts as trophies, and it is not possible to determine the percentage who did. However "their behaviour reflected attitudes which were very widely shared."[3][4] In addition to trophy skulls, teeth, ears and other such objects, taken body parts were occasionally modified, for example by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts.[5] "U.S. Marines on their way to Guadalcanal relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and "pickling" Japanese ears as keepsakes."[6] In an air base in New Guinea hunting the last remaining Japanese was a “sort of hobby”. The leg-bones of these Japanese were sometimes carved into letter openers and pen-holders,[5] but this was rare.[3]

Eugene Sledge, private, Company K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division, also relates a few instances of fellow Marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese dead. In one case, Sledge witnessed an extraction while the Japanese soldier was still alive. A Marine Sledge did not know drifted in after an engagement to take some "spoils." As the Marine drove his knife into the still live soldier, he was promptly shouted down by Sledge and others in Company K, and another Marine ran over and shot the wounded Japanese soldier. The Marine took his prize and drifted away, cursing the others for their humanity. (With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. p 120 )

In 1944 the American poet Winfield Townley Scott was working as a reporter in Rhode Island when a sailor displayed his skull trophy in the newspaper office. This led to the poem The U.S. sailor with the Japanese skull, which described one method for preparation of skulls (the head is skinned, towed in a net behind a ship to clean and polish it, and in the end scrubbed with caustic soda).[7]

In October 1943, the U.S. High Command expressed alarm over recent newspaper articles, for example one where a soldier made a string of beads using Japanese teeth, and another about a soldier with pictures showing the steps in preparing a skull, involving cooking and scraping of the Japanese heads.[7]

Charles Lindbergh refers in his diary to many instances of Japanese with an ear or nose cut off.[7] In the case of the skulls however, most were not collected from freshly killed Japanese; most came from already partially or fully skeletonised Japanese bodies.[7]

Extent of practice

Most U.S. servicemen in the Pacific did not mutilate Japanese corpses. The majority had some knowledge that these practices were occurring, however, and "accepted them as inevitable under the circumstances".[8] The incidence of soldiers collecting Japanese body parts occurred on "a scale large enough to concern the Allied military authorities throughout the conflict and was widely reported and commented on in the American and Japanese wartime press", however.[9] The degree of acceptance of the practice varied between units. Taking of teeth was generally accepted by enlisted men and also by officers, while acceptance for taking other body parts varied greatly.[3]

There is some disagreement between historians over what the more common forms of 'trophy hunting' undertaken by U.S. personnel were. John W. Dower states that ears were the most common form of trophy which was taken, and skulls and bones were less commonly collected. In particular he states that "skulls were not popular trophies" as they were difficult to carry and the process for removing the flesh was offensive.[10] This view is supported by Simon Harrison.[3] In contrast, Niall Ferguson states that "boiling the flesh off enemy [Japanese] skulls to make souvenirs was a not uncommon practice. Ears, bones and teeth were also collected".[11]

The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the campaign, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking.[3] Harrison concludes that since this was the first real opportunity to take such items (the battle of Guadalcanal), "Clearly, the collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered."[3] Eric Bergerud explains the attitudes which led to this behavior by noting that the Marines who fought on Guadalcanal were aware of Japanese atrocities against the defenders of Wake Island, which included the beheading of several Marines, and the Bataan Death March prior to the start of the campaign.[12] When Charles Lindbergh passed through customs at Hawaii in 1944, one of the customs declarations he was asked to make was whether or not he was carrying any bones. He was told after expressing some shock at the question that it had become a routine point.[13] This was because of the large number of souvenir bones discovered in customs, also including “green” (uncured) skulls.[14]

On February 1, 1943, Life magazine published a famous photograph by Ralph Morse which showed the charred, open-mouthed, decapitated head of a Japanese soldier killed by U.S Marines during the Guadalcanal campaign, and propped up below the gun turret of a tank by Marines. The caption read as follows: "A Japanese soldier's skull is propped up on a burned-out Jap tank by U.S. troops." Life received letters of protest from mothers who had sons in the war and others "in disbelief that American soldiers were capable of such brutality toward the enemy." The editors of Life explained that "war is unpleasant, cruel, and inhuman. And it is more dangerous to forget this than to be shocked by reminders."

In 1984 Japanese soldiers' remains were repatriated from the Mariana Islands. Roughly 60 percent were missing their skulls.[14]

Motives

Dehumanization

In the U.S. there was a widely held view that the Japanese were less than human.[15] This view was similar to the one held in Japan toward the US[16] as the Shōwa regime thus preached racial superiority and racialist theories, based on sacred nature of the Yamato-damashii. Thus, while Americans were referred as kichiku (mongrel beast or mongrelized apes),[17] Japanese soldiers were taught to think of all prisoners as not worthy of consideration.[18]

There was also popular anger in U.S. at the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor amplifying pre-war racial prejudices.[11] The U.S. media helped propagate this view of the Japanese, for example describing them as “yellow vermin”.[15]. In an official U.S. Navy film Japanese troops were described as “living, snarling rats”.[19] The mixture of racism, propaganda, and well-publicized Japanese atrocities such as forced labor,[20] cannibalism,[21] vivisection,[22] and torture of POW's,[23] led to intense loathing of the Japanese.[15] Despite the impact of this propaganda, U.S. Army opinion surveys found that the high degree of hatred towards the Japanese expressed by soldiers in training typically declined dramatically once the men entered combat.[24]

The combination of Japanese soldiers' reluctance to surrender and hostile American attitudes to Japanese contributed to the fact that relatively few Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner.[25] The Japanese soldiers, who considered the enemy sub-human, [26] and referred to the Allies as kichiku (rabid mongrel beast),[27][28] seem to have been victims of the same prejudice by the Allied soldiers. According to Niall Ferguson: "To the historian who has specialized in German history, this is one of the most troubling aspects of the Second World War: the fact that Allied troops often regarded the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians – as Untermenschen."[29] Since the Japanese were regarded as animals it is not surprising that the Japanese remains were treated in the same way as animal remains.[15]

Simon Harrison comes to the conclusion in his paper “Skull trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance” that the small minority of U.S. personnel who collected Japanese skulls did so as they came from a society which placed much value in hunting as a symbol of masculinity, combined with a de-humanization of the enemy.

Brutalization

Some writers and veterans state that the body parts trophy and souvenir taking was a side effect of the brutalizing effects of a harsh campaign.[30]

Harrison argues that while brutalization could explain part of the mutilations, this explanation does not explain the servicemen who already before shipping off for the Pacific proclaimed their intention to acquire such objects.[31] He believes that it also does not explain the many cases of servicemen collecting the objects as gifts for people back home.[31] Harrison concludes that there is no evidence that the average serviceman collecting this type of souvenirs was suffering from "combat fatigue". They were normal men who felt this was what their loved ones wanted them to collect for them.[32] Skulls were sometimes also collected as souvenirs by non-combat personnel.[30] Skulls and teeth were also sometimes traded amongst personnel.[30]

Revenge

According to Bergerud U.S. troops who mutilated the bodies of their Japanese opponents were also motivated by a desire to seek revenge against Japanese atrocities, such as the Bataan Death March. For instance, Bergerud states that the U.S. Marines on Guadacanal were aware that the Japanese had committed atrocities against the Marine defenders of Wake Island prior to the start of the campaign[33] and first began taking ears from Japanese corpses after photos of the mutilated bodies of Marines on Wake Island were found in Japanese engineers' personal effects.[34]

U.S. reaction

“Stern disciplinary action” against human remains souvenir taking was ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet as early as September 1942.[3] In October 1943 General George C. Marshall radioed General Douglas MacArthur about “his concern over current reports of atrocities committed by American soldiers”.[35] In January 1944 JCS issued a directive against the taking of Japanese body parts.[35] Directives of this type may have been effective in some areas, "but they seem to have been implemented only partially and unevenly by local commanders".[3]

On May 22 1944 Life Magazine published a photo of an American girl with a Japanese skull sent to her by her naval officer boyfriend.[36] The letters Life received from its readers in response to this photo were "overwhelmingly condemnatory"[37] and the Army directed its Bureau of Public Relations to inform U.S. publishers that “the publication of such stories would be likely to encourage the enemy to take reprisals against American dead and prisoners of war.”[38] The junior officer who had sent the skull was also traced and officially reprimanded.[32]

The Life photo also led to the U.S. Military to take further action against the mutilation of Japanese corpses. In a memorandum dated June 13, 1944, the Army JAG asserted that “such atrocious and brutal policies” in addition to being repugnant also were violations of the laws of war, and recommended the distribution to all commanders of a directive pointing out that “the maltreatment of enemy war dead was a blatant violation of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the sick and wounded, which provided that: After every engagement, the belligerent who remains in possession of the field shall take measures to search for wounded and the dead and to protect them from robbery and ill treatment.” Such practices were in addition also in violation of the unwritten customary rules of land warfare and could lead to the death penalty.[39] The Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that “the atrocious conduct of which some U.S. servicemen were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law”.[39]

On 13 June 1944 the press reported that President Roosevelt had been presented with a letter-opener made out of a Japanese soldier's arm bone by Francis E. Walter, a Democratic congressman.[32] Several weeks later it was reported that it had been given back with the explanation that the President did not want this type of object and recommended it be buried instead. In doing so, Roosevelt was acting in response to the concerns which had been expressed by the military authorities and some of the civilian population, including church leaders.[32]

In October 1944 the Right Rev. Henry St. George Tucker, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, issued a statement which deplored "'isolated' acts of desecration with respect to the bodies of slain Japanese soldiers and appealed to American soldiers as a group to discourage such actions on the part of individuals."[40][41]

Japanese reaction

News that President Roosevelt had been given a bone letter opener by a congressman were widely reported in Japan. The Americans were portrayed as “deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman”. This reporting was compounded by the previous May 22, 1944 Life Magazine picture of the week publication of a young woman with a skull trophy.[42] Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of mutilating the Japanese dead and taking pieces of them home was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings".[42]

Context

All WWII remains discovered in the U.S. attributable to an ethnicity are of Japanese origins; none come from Europe.[5]

Australian soldiers also mutilated Japanese bodies, most commonly by taking gold teeth from corpses. "The vast majority of Australians found such behaviour abhorrent", however, and it was considered a crime by the Australian Army and officially discouraged.[43] In another similarity to the U.S. Army, Australian troops almost never mutilated the bodies of the German and Italian soldiers they faced in North Africa and Greece. Australian soldiers' "unusually murderous behavior" towards their Japanese opponents was caused by racism, a lack of understanding of Japanese military culture and, most significantly, a desire to take revenge against the murder and mutilation of Australian prisoners and native New Guineans during the Battle of Milne Bay and subsequent battles.[44]

Contemporary

Skulls from the Vietnam War and from WWII keep turning up in the U.S., sometimes returned by former servicemen or their relatives, or discovered by police. According to Harrison, contrarily to the situation in average head-hunting societies the trophies do not fit in in the American society. While the taking of the objects was socially accepted at the time, after the war, when the Japanese in time became seen as fully human again, the objects for the most part became seen as unacceptable and unsuitable for display. Therefore in time they and the practice that had generated them were largely forgotten.[14]

See also

References

- ^ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3651/is_199510/ai_n8714274/pg_1 Missing on the home front, National Forum, Fall 1995 by Roeder, George H Jr

- ^ Lewis A. Erenberg, Susan E. Hirsch book: The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II. 1996. Page 52. ISBN 0226215113.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harrison, p.827

- ^ Weingartner, p.56

- ^ a b c Simon Harrison (2006). "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 12: 826.

- ^ James J. Weingartner (1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 556.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Harrison, p.822

- ^ Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy. Race and Power in the Pacific War. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571146058., p. 66

- ^ Harrison, p.818

- ^ Dower, p. 65

- ^ a b Ferguson, Niall (2007). The War of the World. History's Age of Hatred. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141013824., p. 546

- ^ Bergerud, Eric (1997). Touched with Fire. The Land War in the South Pacific. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 01402.46967.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help), p. 407 - ^ Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy. Race and Power in the Pacific War. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571146058., p. 71

- ^ a b c Harrison, p.828

- ^ a b c d Weingartner, p.54

- ^ Navarro Figure 8 and 9 https://www.msu.edu/~navarro6/srop.html

- ^ Navarro Figure 8 and 9 https://www.msu.edu/~navarro6/srop.html

- ^ Barak Kushner, The Thought War, 2006, p. 131, Haruko Taya Cook & Theodore F. Cook, Japan at War 1993, p. 153,

- ^ Weingartner, p.54. Japanese were alternatively described and depicted as “mad dogs”, “yellow vermin”, termites, apes, monkeys, insects, reptiles and bats etc.

- ^ links for research, Allied POWs under the Japanese

- ^ Tanaka, Hidden horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II, Westview press, 1996, p.127.

- ^ see unit 731 or BBC "Japanese doctor admits POW abuse", The Denver Post, June 1, 1995, cited by Gary K. Reynolds, 2002, "U.S. Prisoners of War and Civilian American Citizens Captured and Interned by Japan in World War II: The Issue of Compensation by Japan" (Library of Congress)

- ^ de Jong, Louis (2002). The collapse of a colonial society. The Dutch in Indonesia during the Second World War. Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 206. translation J. Kilian, C. Kist and J. Rudge, introduction J. Kemperman. Leiden, The Netherlands: KITLV Press. pp. 167 170–173 181–184 196 204–225 309–314 323–325 337–338 341 343 345–346 380 407. ISBN 90 6718 203 6.

{{cite book}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Spector, Ronald H. (1984). Eagle Against the Sun. The American War with Japan. London: Cassel & Co. ISBN 0304359793., p. 411

- ^ For a discussion of Allied soldiers "standard practice" ( Niall Ferguson (2004). "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat". War in History. 11: 181.) of killing Japanese prisoners and Japanese attempting to surrender see Allied war crimes during World War II.

- ^ According to a former Japanese Army officer who served in China, Uno Shintaro, stated: The major means of getting intelligence was to extract information by interrogating prisoners. Torture was an unavoidable necessity. Murdering and burying them follows naturally. You do it so you won't be found out. I believed and acted this way because I was convinced of what I was doing. We carried out our duty as instructed by our masters. We did it for the sake of our country. From our filial obligation to our ancestors. On the battlefield, we never really considered the Chinese humans. When you're winning, the losers look really miserable. We concluded that the Yamato [i.e. Japanese] race was superior.Haruko Taya Cook & Theodore F. Cook, Japan at War 1993, p. 153

- ^ David C. Earhart, Certain Victory : Images of World War II in the Japanese Media, 2007

- ^ Navarro Figure 8 and 9 https://www.msu.edu/~navarro6/srop.html

- ^ Ferguson, Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War, p. 182

- ^ a b c Harrison, p.823

- ^ a b Harrison, p.824

- ^ a b c d Harrison, p.825

- ^ Bergerud, p.407

- ^ Bergerud, p.411

- ^ a b Weingartner, p.57

- ^ The image depicts a young blond at a desk gazing at a skull. The caption says “When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: "This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach." Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.

- ^ Weingartner, p.58

- ^ Weingartner, p.60

- ^ a b Weingartner, p.59

- ^ "Tucker Deplores Desecration of Foe; Mutilation of Japanese Bodies Contrary to Spirit of Army, He Says of 'Isolated' Cases". The New York Times. 1944-10-14.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The Morals of Victory". Time. 1944-10-23. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Harrison, p.833

- ^ Johnston, Mark (2000). Fighting the Enemy. Australian Soldiers and their Adversaries in World War II. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521782228. p.82

- ^ Johnston, pp. 84–100

Further reading

- Paul Fussell "Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War"

- Bourke "An Intimate History of Killing" (pages 37–43)

- Dower "War without mercy: race and power in the Pacific War" (pages 64–66)

- Fussel "Thank God for the Atom Bomb and other essays" (pages 45–52)

- Aldrich "The Faraway War: Personal diaries of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific"

- Hoyt "Japan's war: the great Pacific conflict"

- Charles A. Lindbergh (1970). The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

External links

- One War Is Enough War Correspondent EDGAR L. JONES 1946

- American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs'

- The US Sailor with the Japanese Skull by Winfield Townley Scott

- Eerie Souvenirs From the Vietnam War Washington Post July 3, 2007 By Michelle Boorstein]

- 2002 Virginia Festival of the Book: Trophy Skulls

- War against subhumans: comparisons between the German War against the Soviet Union and the American war against Japan, 1941-1945 The Historian 3/22/1996, Weingartner, James

- Racism in Japanese in U.S. wartime propaganda The Historian 6/22/1994 Brcak, Nancy; Pavia, John R.

- MACABRE MYSTERY Coroner tries to find origin of skull found during raid by deputies The Pueblo Chieftain Online.

- Skull from WWII casualty to be buried in grave for Japanese unknown soldiers Stars and Stripes

- HNET review of Peter Schrijvers. The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II.

- The May 1944 Life Magazine picture of the week (Image)