Janusz Korczak: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 167.93.37.189 identified as vandalism to last revision by VasilievVV. (TW) |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

===Russian Empire=== |

|||

asshole! |

|||

Korczak was born in [[Warsaw]] to an assimilated [[Jew]]ish family. His mother Cecylia Głębicka was the daughter of prominent [[Kalisz]] Jews and his father Józef Goldszmit was from a family of proponents of the [[haskalah]]. Korczak's father died in 1896, possibly by his own hand, leaving the family without a source of income. Over the next few years, the family was forced to abandon their spacious apartment and, during his teens, Korczak was the sole breadwinner for his mother, sister, and grandmother. |

|||

In 1898 he used ''Janusz Korczak'' as a writing [[pseudonym]] in [[Ignacy Paderewski]]'s literary contest. The name originated from the book ''Janusz Korczak and the Pretty Swordsweeperlady'' by [[Józef Ignacy Kraszewski]]. In 1890s he studied in the [[Flying University]]. In the years 1898–1904 Korczak studied medicine at the [[University of Warsaw]] and also wrote for several [[Polish language]] newspapers. |

|||

After his graduation he became a [[pediatric]]ian. During the [[Russo-Japanese War]] in 1905–1906 he served as a military doctor. Meanwhile his book ''[[Child of the Drawing Room]]'' gained him some literary recognition. After the war he continued his practice in Warsaw. |

|||

[[Image:Krochmalna Street orphanage.PNG|250px|thumb|The Krochmalna Street orphanage where Korczak worked. He lived in a room at the [[attic]]]] |

|||

In 1907–1908 Korczak continued his studies in [[Berlin]]. When he was working for the Orphan's Society in 1909 he met [[Stefania Wilczyńska]]. In 1911–1912 he became a director of ''Dom Sierot'', the [[orphanage]] of his own design for Jewish children in Warsaw. He took Wilczyńska as his closest associate. There he formed a kind-of-a-[[republic]] for children with its own small [[parliament]], [[court]] and newspaper. He reduced his other duties as a doctor. |

|||

In 1914 Korczak again became a military doctor with the rank of [[Lieutenant]] during [[World War I]]. During the [[Polish-Soviet War]] he served again as a military doctor with the rank of major but was assigned to Warsaw after a brief stint in [[Łódź]] |

|||

===Poland=== |

===Poland=== |

||

Revision as of 18:13, 12 April 2010

Janusz Korczak | |

|---|---|

Janusz Korczak | |

| Born | July 22, 1878 |

| Died | August 1942 |

| Occupation(s) | Children's author, humanitarian, pediatrician and child pedagogue |

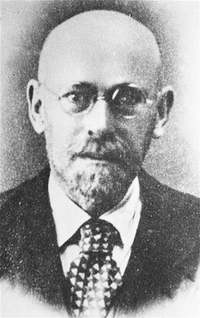

Janusz Korczak, the pen name of Henryk Goldszmit (July 22, 1878 – August 1942) was a Polish-Jewish children's author, pediatrician, and child pedagogue, known as Pan Doktor (Mr Doctor) or Stary Doktor (Old Doctor).

Biography

Russian Empire

Korczak was born in Warsaw to an assimilated Jewish family. His mother Cecylia Głębicka was the daughter of prominent Kalisz Jews and his father Józef Goldszmit was from a family of proponents of the haskalah. Korczak's father died in 1896, possibly by his own hand, leaving the family without a source of income. Over the next few years, the family was forced to abandon their spacious apartment and, during his teens, Korczak was the sole breadwinner for his mother, sister, and grandmother.

In 1898 he used Janusz Korczak as a writing pseudonym in Ignacy Paderewski's literary contest. The name originated from the book Janusz Korczak and the Pretty Swordsweeperlady by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski. In 1890s he studied in the Flying University. In the years 1898–1904 Korczak studied medicine at the University of Warsaw and also wrote for several Polish language newspapers.

After his graduation he became a pediatrician. During the Russo-Japanese War in 1905–1906 he served as a military doctor. Meanwhile his book Child of the Drawing Room gained him some literary recognition. After the war he continued his practice in Warsaw.

In 1907–1908 Korczak continued his studies in Berlin. When he was working for the Orphan's Society in 1909 he met Stefania Wilczyńska. In 1911–1912 he became a director of Dom Sierot, the orphanage of his own design for Jewish children in Warsaw. He took Wilczyńska as his closest associate. There he formed a kind-of-a-republic for children with its own small parliament, court and newspaper. He reduced his other duties as a doctor.

In 1914 Korczak again became a military doctor with the rank of Lieutenant during World War I. During the Polish-Soviet War he served again as a military doctor with the rank of major but was assigned to Warsaw after a brief stint in Łódź

Poland

In 1926 Korczak let the children begin their own newspaper, the Mały Przegląd (Little Review), as a weekly attachment to the daily Polish-Jewish Newspaper Nasz Przegląd (Our Review). In these years his secretary was the noted Polish novelist Igor Newerly.

During the 1930s he had his own radio program until it was cancelled due to complaints from anti-semites. In 1933 he was awarded the Silver Cross of the Polonia Restituta. In 1934–1936 Korczak traveled yearly to Mandate Palestine and visited its kibbutzim. That led to increasing anti-semitic attacks in the Polish press. It additionally spurred his estrangement with the non-Jewish orphanage he had been working for. Still, he refused to move to Palestine even when Wilczyńska went to live there for a year in 1938.

The Holocaust

In 1939, when World War II erupted, Korczak volunteered for duty in the Polish Army but was refused due to his age. He witnessed the Wehrmacht taking over Warsaw. When the Germans created the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, his orphanage was forced to move to the ghetto. Korczak moved in with them. In July, Janusz Korczak decided that the children in the orphanage should put on Rabindranath Tagore’s play, the Post Office.

On August 5 (some say August 6), 1942, German soldiers came to collect the 192 (there is some debate about the actual number and it may have been 196) orphans and about one dozen staff members to take them to Treblinka extermination camp. Korczak had been offered sanctuary on the “Aryan side” by Zegota but turned it down repeatedly, saying that he could not abandon his children. Now too, he refused offers of sanctuary, insisting that he would go with the children. The children were dressed in their best clothes, and each carried a blue knapsack and a favorite book or toy. Joshua Perle, an eyewitness, described the procession of Korczak and the children through the ghetto to the Umschlagplatz (deportation point to the death camps):

- ... A miracle occurred. Two hundred children did not cry out. Two hundred pure souls, condemned to death, did not weep. Not one of them ran away. None tried to hide. Like stricken swallows they clung to their teacher and mentor, to their father and brother, Janusz Korczak, so that he might protect and preserve them. Janusz Korczak was marching, his head bent forward, holding the hand of a child, without a hat, a leather belt around his waist, and wearing high boots. A few nurses were followed by two hundred children, dressed in clean and meticulously cared for clothes, as they were being carried to the altar. (...) On all sides the children were surrounded by Germans, Ukrainians, and this time also Jewish policemen. They whipped and fired shots at them. The very stones of the street wept at the sight of the procession.

According to a popular legend, when the group of orphans finally reached the Umschlagplatz, an SS officer recognized Korczak as the author of one of his favorite children's books and offered to help him escape. By another version, the officer was acting officially, as the Nazi authorities had in mind some kind of "special treatment" for Korczak (some prominent Jews with international reputations got sent to Theresienstadt). Whatever the offer, Korczak once again refused. He boarded the trains with the children and was never heard from again.

Korczak's evacuation from the Ghetto is also mentioned in Władysław Szpilman's book The Pianist:

- One day, around 5th August, when I had taken a brief rest from work and was walking down Gęsia Street, I happened to see Janusz Korczak and his orphans leaving the ghetto. The evacuation of the Jewish orphanage run by Janusz Korczak had been ordered for that morning. The children were to have been taken away alone. He had the chance to save himself, and it was only with difficulty that he persuaded the Germans to take him too. He had spent long years of his life with children and now, on this last journey, he could not leave them alone. He wanted to ease things for them. He told the orphans they were going out in to the country, so they ought to be cheerful. At last they would be able to exchange the horrible suffocating city walls for meadows of flowers, streams where they could bathe, woods full of berries and mushrooms. He told them to wear their best clothes, and so they came out into the yard, two by two, nicely dressed and in a happy mood. The little column was led by an SS man who loved children, as Germans do, even those he was about to see on their way into the next world. He took a special liking to a boy of twelve, a violinist who had his instrument under his arm. The SS man told him to go to the head of the procession of children and play – and so they set off. When I met them in Gęsia Street, the smiling children were singing in chorus, the little violinist was playing for them and Korczak was carrying two of the smallest infants, who were beaming too, and telling them some amusing story. I am sure that even in the gas chamber, as the Zyklon B gas was stifling childish throats and striking terror instead of hope into the orphans' hearts, the Old Doctor must have whispered with one last effort, ‘it's all right, children, it will be all right’. So that at least he could spare his little charges the fear of passing from life to death."[1]

Some time after, there were rumors that the trains had been diverted and that Korczak and the children had survived. There was, however, no basis to these stories. Most likely, Korczak was killed with most of his children in a gas chamber upon their arrival at Treblinka. There is a cenotaph for him at the Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw.

Pedagogical influence

Korczak was one of the first pedagogues who changed the general attitudes of teachers and parents towards students and children. His general concept was that any child has his own way, his own path, on which he embarks immediately following birth. The role of a parent or a teacher is not to impose other goals on a child, but to help children achieve their own goals. His book How to Love a Child begins with the following sentence:

You are saying: "Children are annoying"

You clarify: "You need to always kneel to their perceptions".

You are wrong.

Because you actually need to tip-toe to their perceptions and ideals.

In the book, he shares much of his experience dealing with difficult children.

Korczak's ideas were further developed by many other pedagogues such as Simon Soloveychik and Erich Dauzenroth.

Themes in the children's books

Korczak often employed the form of the fairy tale in order to actually prepare his young readers for the dilemmas and difficulties of real adult life, and the need to take responsible decisions.

In the 1923 King Matthew the First (Król Maciuś Pierwszy) and its sequel King Matthew on the Desert Island (Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej) Korczak depicted a child prince who is catapulted to the throne by the sudden death of his father, and who must learn from various mistakes.

He tries to read and answer all his mail by himself and finds that the volume is too much and he needs to rely on secretaries; he is exasperated with his ministers and has them arrested, but soon realises that he does not know enough to govern by himself, and is forced to release the ministers and institute constitutional monarchy; when a war breaks out he does not accept being shut up in his palace, but slips away and joins up, pretending to be a peasant boy - and narrowly avoids becoming a POW; he takes the offer of a friendly journalist to publish for him a "royal paper" -and finds much later that he gets carefully-edited news and that the journalist is covering up the gross corruption of the young king's best friend; he tries to organise the children of all the world to hold processions and demand their rights - and ends up antagonising other kings; he falls in love with a black African princess and outrages racist opinion (by modern standards, however, Korczak's depiction of blacks is itself not completely free of stereotypes which were current at the time of writing); finally, he is overthrown by the invasion of three foreign armies and exiled to a desert island, where he must come to terms with reality - and finally does.

The later Kajtuś the Wizard (Kajtuś czarodziej) (1935) anticipated Harry Potter in depicting a schoolboy who gains magic powers (and its popularity during the 1930s, in both Polish and in translation to several other languages, was nearly comparable to the present popularity of the Potter series). Kajtuś has, however, a far more difficult path than Harry Potter: he has no Hogwarts-type School of Magic where he could be taught by expert mages, but must learn to use and control his powers all by himself - and most importantly, to learn his limitations.

Selected writings

Fiction

- Children of the Streets (Dzieci ulicy, Warsaw 1901)

- Koszałki Opałki (Warsaw, 1905)

- Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu, Warsaw 1906, 2nd edition 1927) – partially autobiographical

- Mośki, Joski i Srule (Warsaw 1910)

- Józki, Jaśki i Franki (Warsaw 1911)

- Fame (Sława, Warsaw 1913, corrected 1935 and 1937)

- Bobo (Warsaw 1914)

- King Matt the First (Król Maciuś Pierwszy, Warsaw 1923) ISBN 1-56512-442-1

- King Matt on a Deserted Island (Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej, Warsaw 1923)

- Bankruptcy of Little Jack (Bankructwo małego Dżeka, Warsaw 1924)

- When I Am Little Again (Kiedy znów będę mały, Warsaw 1925)

- Senat szaleńców, humoreska ponura (a screenplay for the Ateneum theatre in Warsaw 1931)

- Kajtus the Wizard (Kajtuś czarodziej, Warsaw 1935)

Pedagogical books

- Momenty wychowawcze (Warsaw, 1919, 2nd edition 1924)

- How to Love a Child (Jak kochać dziecko, Warsaw 1919, 2nd edition 1920 as Jak kochać dzieci)

- The Child's Right to Respect (Prawo dziecka do szacunku, Warsaw, 1929)

- Playful pedagogy (Pedagogika żartobliwa, Warsaw, 1939)

Other books

- Diary (Pamiętnik, Warsaw, 1958)

- The Stubborn Boy: The Life of Pasteur (Warsaw, 1935)

In popular culture

Stage plays:

- Dr Korczak and the Children by Erwin Sylvanus (1957)

- Korczak's Children by Jeffrey Hatcher (2003)

- Dr Korczak's Example by David Greig (2001) [1]

- The Children's Republic by Hannah Moscovitch (2009)

Television:

- Studio 4: Dr Korczak and the Children - BBC adaptation of Sylvanus's play, written and directed by Rudolph Cartier (13 March 1962)

Film:

- Korczak, written by Agnieszka Holland, directed by Andrzej Wajda (1990)

Operas:

- "King Matt the First" - opera for/by children, music by Lev Konov, libretto by Lev Konov, Olga Zhukova, Ali Ibragimov (1988,1992) Moscow

- Korczak's Orphans - music by Adam Silverman, libretto by Susan Gubernat (2003)

Books:

- Milkweed - by Jerry Spinelli (2003) - Doctor Korczak runs an orphanage in Warsaw where the main character often visits him

- Moshe en Reizele (Mosje and Reizele) (2004) - by Karlijn Stoffels - Mosje is sent to live in Korczak's orphanage, where he falls in love with Reizele. Set in the period 1939-1942. Original Dutch, German translation available. No English version at time of writing (March 2009).

Astronomy:

- Asteroid 2163 Korczak is named in his honor.

References

- ^ The Pianist - Page 96

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2009) |

Further reading

- Bystrzycka, Anna. "Dzieci z sierocińca". Zwrot. 7 (2007): 30–31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Joseph, Sandra (1999). A Voice for the Child: The inspirational words of Janusz Korczak. Collins Publishers.

- Lifton, Betty Jean (1988). The King of Children: A Biography of Janusz Korczak. Collins Publishers.

- Mortkowicz-Olczakowa, Hanna (1961). Bunt wspomnień. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- Parenting Advice from a Polish Holocaust Hero from National Public Radio

- Lawrence Kohlberg (1981). The Philosophy of Moral Development: Education for Justice pp. 401-408. Harper & Row, Publishers, San Francisco.

External links

- Janusz Korczak Biography, The King of Children: The Life and Death of Janusz Korczak by Betty Jean Lifton

- Janusz Korczak Living Heritage Association

- Ojemba Productions presents 'KORCZAK' at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2005!

- Pole Apart - The Life and Work of Janusz Korczak

- Lev Konov - opera "King Matt the First" for/by children. Audio (1992) Part 1 of 6.

- Korczak's Orphans opera by Adam Silverman and Susan Gubernat

- I'm small, but important, German Documentary by Walther Petri and Konrad Weiss

- Lewowicki, Tadeusz: Janusz Korczak. (PDF-File, 43 KB) Prospects:the quarterly review of comparative education, vol. XXIV, no. 1/2, 1994, p. 37–48.

- 1878 births

- 1942 deaths

- Humanists

- Jewish writers

- Physicians who died in Nazi concentration camps

- Polish civilians killed in World War II

- Polish educationists

- Polish humanitarians

- Polish Jews

- Polish murder victims

- Polish pediatricians

- Polish people of World War II

- Polish writers

- Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Recipients of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

- Treblinka extermination camp victims