Venus (mythology): Difference between revisions

Beanangel300 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Beanangel300 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

* [[Venus Kallipygos]] |

* [[Venus Kallipygos]] |

||

* [[:Image:Venus pudica Massimo.jpg|Venus Pudica]] |

* [[:Image:Venus pudica Massimo.jpg|Venus Pudica]] |

||

[[Lilith]] with the |

[[Lilith]] with the | <font size="11">♀</font> |

||

symbol about 1950 BY2K |

|||

[[File:Lilith a few milennia ago.PNG]] |

[[File:Lilith a few milennia ago.PNG]] |

||

Revision as of 04:11, 12 May 2010

| Venus | |

|---|---|

| Equivalents | |

| Greek equivalent | Aphrodite |

Venus was a major Roman goddess principally associated with love, beauty and fertility, who played a key role in many Roman religious festivals and myths. From the third century BC, the increasing Hellenization of Roman upper classes identified her as the equivalent of the Greek goddess Aphrodite.

Etymology

The noun form Venus means "love" and "sexual desire" in Latin[1] and has connections to venerari (to honour, to try to please) and venia (grace, favour) through a possible common root in an Indo-European *venes-, comparable to Sanskrit van (love, honour).[2] Venus' name might embody the function of honours and gifts to the divine when seeking their favours: such acts can be interpreted as the enticement, seduction or charm of gods by mortals.[3][4] The ambivalence of this function is suggested in the etymological relationship of the root *venes- with Latin venenum (poison, venom), in the sense of "a charm, magic filter".[5]

Venus in mythology

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

| Related topics |

Venus was commonly associated with the Greek goddess Aphrodite and the Etruscan deity Turan, borrowing aspects from each. As with most other gods and goddesses in Roman mythology, the literary concept of Venus is mantled in whole-cloth borrowings from the literary Greek mythology of her equivalent counterpart, Aphrodite. The early, Etruscan or Latin goddess of vegetation and gardens became deliberately associated with the Greek Goddess Aphrodite.[6] In some Latin mythology Eros was the son of Venus and Mars, the god of war. In other times, Venus was understood to be the consort of Vulcan. Virgil, in compliment to his patron Augustus and the gens Julia, made Venus, whom Julius Caesar had adopted as his protectress, the ancestor of the Roman people by way of its legendary founder Aeneas and his son Iulus.

Cult

Her cult began in Ardea and Lavinium, Latium. On August 15, 293 BC, her oldest-known temple was dedicated, and August 18 became a festival called the Vinalia Rustica. After Rome's defeat at the Battle of Lake Trasimene in the opening episodes of the Second Punic War, the Sibylline oracle recommended the importation of the Sicillian Venus of Eryx; a temple to her was dedicated on the Capitoline Hill in 217 BC:[7] a second temple to her was dedicated in 181 BC.[8]

For some Romans, Venus seems to have played a part in household religion. Julius Caesar claimed her as an ancestor (Venus Genetrix); possibly a long-standing family tradition, certainly one adopted as such by his heir Augustus. Venus statuettes have been found in quite ordinary household shrines (lararia): Petronius places one among the Lares of Trimalchio's household shrine.[9]

Epithets

Like other major Roman deities, Venus was ascribed a number of epithets to refer to different aspects or roles of the goddess.

Venus Acidalia was,[10] according to Servius, derived from the well Acidalius near Orchomenus, in which Venus used to bathe with the Graces; others connect the name with the Greek acides (άκιδες), i.e. cares or troubles.[11]

Venus Calva ("Venus the bald one"), this is the first known cult of the goddess, dating back to least the beginning of the IV century B.C. The epithet refers to hair as one of most important instruments of feminine charm. There are two traditions concerning the origin of the epithet. One wants that it is a way of commemorating the sacrifice of their hair by the Roman matronae to make cables for war machines during the siege laid by the Gauls. Another refers it to the sacrifice of their hair they made under king Ancus Marcius, when an epidemic had rendered bald the queen and other women, to obtain from the goddess that they grew new hair.[12]

Venus Cloacina ("Venus the Purifier"), was a fusion of Venus with the Etruscan water goddess Cloacina, likely resulting from a statue of Venus being prominent near the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's sewer system. The statue was erected on the spot where peace was concluded between the Romans and Sabines.

Venus Erycina ("Venus from Eryx"), also called Venus Erucina, originated on Mount Eryx in western Sicily. Temples were erected to her on the Capitoline Hill and outside the Porta Collina. She embodied "impure" love, and was the patron goddess of prostitutes.

Venus Felix ("Lucky Venus") was an epithet used for a temple on the Esquiline Hill and for a temple constructed by Hadrian dedicated to "Venus Felix et Roma Aeterna" ("Favorable Venus and Eternal Rome") on the north side of the Via Sacra. This epithet is also used for a specific sculpture at the Vatican Museums.

Venus Genetrix ("Mother Venus") was Venus in her role as the ancestress of the Roman people, a goddess of motherhood and domesticity. A festival was held in her honor on September 26. As Venus was regarded as the mother of the Julian gens in particular, Julius Caesar dedicated a temple to her in Rome. This name has also attached to an iconological type of statue of Aphrodite/Venus.

Venus Kallipygos ("Venus with the pretty bottom"), a form worshipped at Syracuse.

Venus Libertina ("Venus the Freedwoman") was an epithet of Venus that probably arose from an error, with Romans mistaking lubentina (possibly meaning "pleasurable" or "passionate") for libertina. Possibly related is Venus Libitina, also called Venus Libentina, Venus Libentia, Venus Lubentina, Venus Lubentini and Venus Lubentia, an epithet that probably arose from confusion between Libitina, a funeral goddess, and the aforementioned lubentina, leading to an amalgamation of Libitina and Venus. A temple was dedicated to Venus Libitina on the Esquiline Hill.

Venus Murcia ("Venus of the Myrtle") was an epithet that merged the goddess with the little-known deity Murcia or Murtia. Murcia was associated with the myrtle-tree, but in other sources was called a goddess of sloth and laziness.

Venus Obsequens ("Graceful Venus" or "Indulgent Venus") was an epithet to which a temple was dedicated in the late 3rd century BCE during the Third Samnite War by Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges. It was built with money fined from women who had been found guilty of adultery. It was the oldest temple of Venus in Rome, and was probably situated at the foot of the Aventine Hill near the Circus Maximus. Its dedication day, August 19, was celebrated in the Vinalia Rustica.

Venus Urania ("Heavenly Venus") was an epithet used as the title of a book by Basilius von Ramdohr, a relief by Pompeo Marchesi, and a painting by Christian Griepenkerl. (cf. Aphrodite Urania.)

On April 1, the Veneralia was celebrated in honor of Venus Verticordia ("Venus the Changer of Hearts"), the protector against vice. A temple to Venus Verticordia was built in Rome in 114 BC, and dedicated April 1, at the instruction of the Sibylline Books to atone for the inchastity of three Vestal Virgins.

Venus Victrix ("Venus the Victorious") was an aspect of the armed Aphrodite that Greeks had inherited from the East, where the goddess Ishtar "remained a goddess of war, and Venus could bring victory to a Sulla or a Caesar."[13] Pompey, Sulla's protege, vied with Caesar for public recognition as her protege, and in 55 BC dedicated a temple at the top of his theater in the Campus Martius. She had a shrine on the Capitoline Hill, and festivals on August 12 and October 9. A sacrifice was annually dedicated to her on the latter date. In neo-classical art, her epithet as Victrix is often used in the sense of 'Venus Victorious over men's hearts' or in the context of the Judgement of Paris (eg Canova's Venus Victrix, a half-nude reclining portrait of Pauline Bonaparte).

Other significant epithets for Venus included Venus Amica ("Venus the Friend"), Venus Armata ("Armed Venus"), Venus Caelestis ("Celestial Venus"), and Venus Aurea ("Golden Venus").

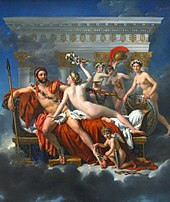

In art

Classical art

Roman and Hellenistic art produced many variations on the goddess, often based on the Praxitlean type Aphrodite of Cnidus. Many female nudes from this period of sculpture whose subjects are unknown are in modern art history conventionally called 'Venus'es, even if they originally may have portrayed a mortal woman rather than operated as a cult statue of the goddess.

Examples include:

- Venus de Milo (130 BCE)

- Venus de' Medici

- Capitoline Venus

- Esquiline Venus

- Venus Felix

- Venus of Arles

- Venus Anadyomene (also here)

- Venus, Pan and Eros

- Venus Genetrix

- Venus of Capua

- Venus Kallipygos

- Venus Pudica

Lilith with the | ♀ symbol about 1950 BY2K

File:Lilith a few milennia ago.PNG

In non-classical art

Venus became a popular subject of painting and sculpture during the Renaissance period in Europe. As a "classical" figure for whom nudity was her natural state, it was socially acceptable to depict her unclothed. As the goddess of sexual healing, a degree of erotic beauty in her presentation was justified, which appealed to many artists and their patrons. Over time, venus came to refer to any artistic depiction in post-classical art of a nude woman, even when there was no indication that the subject was the goddess.

- The Birth of Venus (Botticelli) (c. 1485)

- Sleeping Venus (c. 1501)

- Venus of Urbino (1538)

- Rokeby Venus

- Olympia (1863)

- The Birth of Venus (Bouguereau) (1879)

- The Birth of Venus (Cabanel) (1863)

- Venus of Cherchell, Gsell museum in Algeria

- Venus Victrix, and Venus Italica by Antonio Canova

In the field of prehistoric art, since the discovery in 1908 of the so-called "Venus of Willendorf" small Neolithic sculptures of rounded female forms have been conventionally referred to as Venus figurines. Although the name of the actual deity is not known, the knowing contrast between the obese and fertile cult figures and the classical conception of Venus has raised resistance to the terminology.

Tannhäuser

The medieval German legend Tannhäuser preserved the Venus myth long after her worship was extirpated by Christianity.

The German story tells of Tannhäuser, a knight and poet who found Venusburg, a mountain with caverns containing the subterranean home of Venus, and spent a year there worshipping the goddess. After leaving Venusburg, Tannhäuser is filled with remorse, and travels to Rome to ask Pope Urban IV if it is possible to be absolved of his sins.

Urban replies that forgiveness is as impossible as it would be for his papal staff to blossom. Three days after Tannhäuser's departure, Urban's staff blooms with flowers; messengers are sent to retrieve the knight, but he has already returned to Venusburg, never to be seen again.

Other goddesses of love

Additionally, Venus has been compared to other goddesses of love, Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli in Aztec mythology, Kukulcan in Maya mythology, Frigg and Freyja in the Norse mythos, Anahita in Iranian mythology and Ushas in Vedic religion. Ushas is also linked to Venus by a Sanskrit epithet ascribed to her, vanas- ("loveliness; longing, desire"), which is cognate to Venus, suggesting a Proto-Indo-European link via the reconstructed stem *wen- "to desire".[14]

Venus is also associated with the Latvian god Auseklis, whose name derives from the root aus-, meaning "dawn". Auseklis and Mēness, whose name means "moon", are both Dieva dēli ("sons of God").

See also

- Venus (disambiguation) for links to the planet, the symbol, people and places of this name, artistic creations, etc.

- Other goddesses such as:

References

- ^ http://www.behindthename.com/name/venus

- ^ William W.Skeat Etymological Dictionary of the English Language New York, 1963 (first ed. 1882) s. v. venerable, venereal, venial.

- ^ R. Schilling La religion romaine de Venus depuis les origines jusqu'au temps d' Auguste Pais, 1954, pp.13-64

- ^ R. Schiling "la relation Venus venia", Latomus, 21, 1962, pp. 3-7

- ^ Linked through an adjectival form *venes-no-: ibid. s.v. "venom"

- ^ [1]

- ^ Beard et al, Vol 1., 80, 83: see also Livy Ab Urbe Condita 23.31.

- ^ Orlin, in Rüpke (ed), 62.

- ^ Kaufmann-Heinimann, in Rüpke (ed), 197 - 8.

- ^ Virgil, Aeneid i. 720

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867), "Acidalia", in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. 1, Boston, MA, p. 12

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ R. Schilling La religion romaine de Venus depuis les origines jusqu'au temps d'August Paris, 1954, pp.83-89: "L'origine probable du cult de Venus"

- ^ Thus Walter Burkert, in Homo Necans (1972) 1983:80, noting C. Koch on "Venus Victrix" in Realencyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, 8 A860-64.

- ^ "wen-1. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000". Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- Champeaux, J. (1987). Fortuna. Recherches sur le culte de la Fortuna à Rome et dans le monde romain des origines à la mort de César. II. Les Transformations de Fortuna sous le République. Rome: Ecole Française de Rome. (pp. 378–395)

- Hammond, N.G.L. and Scullard, H.H. (eds.) (1970). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (p. 113)

- Lloyd-Morgan, G. (1986). "Roman Venus: public worship and private rites." In M. Henig and A. King (eds.), Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire (pp. 179–188). Oxford: Oxford Committee for Archaeology Monograph 8.

- Nash, E. (1962). Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Rome Volume 1. London: A. Zwemmer Ltd. (pp. 272–263, 424)

- Richardson, L. (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. (pp. 92, 165–167, 408–409, 411)

- Room, A. (1983). Room's Classical Dictionary. London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (pp. 319–322)

- Rüpke, Jörg (Editor), A Companion to Roman Religion, Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4051-2943-5

- Schilling, R. (1982) (2nd ed.). La Religion Romaine de Vénus depuis les origines jusqu'au temps d'Auguste. Paris: Editions E. de Boccard.

- Scullard, H.H. (1981). Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic. London: Thames and Hudson. (pp. 97, 107)

- Simon, E. (1990). Die Götter der Römer. Munich: Hirmer Verlag. (pp. 213–228).

- Weinstock, S. (1971). Divus Julius. Oxford; Clarendon Press. (pp. 80–90)

- Gerd Scherm, Brigitte Tast Astarte und Venus. Eine foto-lyrische Annäherung (1996), ISBN 3-88842-603-0

External links

- 'Venus Chiding Cupid for Learning to Cast Accounts' by Sir Joshua Reynolds at the Lady Lever Art Gallery

Ancient source references

- Ovid, Metamorphoses IV.171-189

- Cicero, De natura deorum II.20.53

- Lactantius, Divinae institutiones I.17.10

- Justine, Epitome Historiarum philippicarum Pompei Trogi XVIII.5.4, XXI.3.2