Periscope: Difference between revisions

formality |

→Early examples: Some details regarding the Gundlach periscope |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Periscopes, in some cases fixed to [[Periscope rifle|rifles]], served in [[World War I]] to enable soldiers to see over of the tops of trenches, so that they would not be exposed to enemy fire (especially from snipers).<ref name="FIRST">''First World War'' - Willmott, H.P.; [[Dorling Kindersley]], 2003, Page 111</ref> |

Periscopes, in some cases fixed to [[Periscope rifle|rifles]], served in [[World War I]] to enable soldiers to see over of the tops of trenches, so that they would not be exposed to enemy fire (especially from snipers).<ref name="FIRST">''First World War'' - Willmott, H.P.; [[Dorling Kindersley]], 2003, Page 111</ref> |

||

Periscopes are extensively used in [[tank]]s, enabling drivers or tank commanders to inspect their situation without leaving the safety of the tank. An important development, [[Rudolf Gundlach|Gundlach |

Periscopes are extensively used in [[tank]]s, enabling drivers or tank commanders to inspect their situation without leaving the safety of the tank. An important development, the [[Rudolf Gundlach|Gundlach Rotary Periscope]] incorporated a rotating top, which allowed a tank commander to obtain a 360 degree field of view without moving his seat. This design, patented by [[Rudolf Gundlach]] in 1936, was first used in the [[Polish Army|Polish]] [[7-TP]] light tank (produced from 1935 to 1939). As a part of Polish-British pre-[[World War II]] military cooperation, the patent was sold to Vickers-Armstrong for use in [[British Army|British]] tanks, including the ''[[Crusader tank|Crusader]]'', ''[[Churchill tank|Churchill]]'', ''[[Valentine tank|Valentine]]'', and ''[[Cromwell tank|Cromwell]]''. The technology was also transferred to the [[United States Army|American Army]] for use in its tanks, including the ''[[M4 Sherman|Sherman]]''. The [[Red Army|USSR]] later copied the design and used it extensively in its tanks (including the [[T-34]] and [[T-70]]); [[Wehrmacht|Germany]] also made and used copies.<ref>Not Only Enigma... Major Rudolf Gundlach (1892-1957) and His Invention), Warsaw-London, 1999</ref> |

||

The design was first used in the [[Polish Army|Polish]] [[7-TP]] light tank (produced from 1935 to 1939). Shortly before [[World War II]] it was given{{By whom|date=May 2010}} to the [[British Army|British]] <ref>Not Only Enigma... Major Rudolf Gundlach (1892-1957) and His Invention), Warsaw-London, 1999</ref> and was used in most tanks of World War II, including the British ''[[Crusader tank|Crusader]]'', ''[[Churchill tank|Churchill]]'', ''[[Valentine tank|Valentine]]'', and ''[[Cromwell tank|Cromwell]]'' and the [[United States Army|American]] ''[[M4 Sherman|Sherman]]''. The [[Red Army|USSR]] later copied the design and used it extensively in its tanks (including the [[T-34]] and [[T-70]]); [[Wehrmacht|Germany]] also made and used copies. |

|||

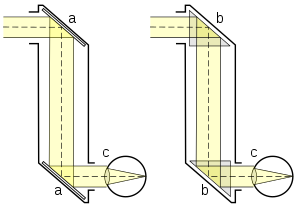

Periscopes proved useful in [[trench warfare]], as seen in the illustrations, representative of action at [[Gallipoli]] in 1915. |

Periscopes proved useful in [[trench warfare]], as seen in the illustrations, representative of action at [[Gallipoli]] in 1915. |

||

Revision as of 12:20, 29 June 2010

A periscope is an instrument for observation from a concealed position. In its simplest form it consists of a tube with mirrors at each end set parallel to each other at a 45-degree angle. This form of periscope, with the addition of two simple lenses, served for observation purposes in the trenches during World War I. Military personnel also use periscopes in some gun turrets and in armored vehicles.

More complex periscopes, using prisms instead of mirrors, and providing magnification, operate on submarines. The overall design of the classical submarine periscope is very simple: two telescopes pointed into each other. If the two telescopes have different individual magnification, the difference between them causes an overall magnification or reduction.

Early examples

Johann Gutenberg, better known for his contribution to printing technology, marketed a kind of periscope in the 1430s to enable pilgrims to see over the heads of the crowd at the vigintennial religious festival at Aachen. Johannes Hevelius described an early periscope with lenses in 1647 in his work Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio [Selenography, or an account of the Moon]. Hevelius saw military applications for his invention. Simon Lake used periscopes in his submarines in 1902. Sir Howard Grubb perfected the device in World War I.[1] Morgan Robertson (1861–1915) claimed[citation needed] to have tried to patent the periscope: he described a submarine using a periscope in his fictional works.

Periscopes, in some cases fixed to rifles, served in World War I to enable soldiers to see over of the tops of trenches, so that they would not be exposed to enemy fire (especially from snipers).[2]

Periscopes are extensively used in tanks, enabling drivers or tank commanders to inspect their situation without leaving the safety of the tank. An important development, the Gundlach Rotary Periscope incorporated a rotating top, which allowed a tank commander to obtain a 360 degree field of view without moving his seat. This design, patented by Rudolf Gundlach in 1936, was first used in the Polish 7-TP light tank (produced from 1935 to 1939). As a part of Polish-British pre-World War II military cooperation, the patent was sold to Vickers-Armstrong for use in British tanks, including the Crusader, Churchill, Valentine, and Cromwell. The technology was also transferred to the American Army for use in its tanks, including the Sherman. The USSR later copied the design and used it extensively in its tanks (including the T-34 and T-70); Germany also made and used copies.[3]

Periscopes proved useful in trench warfare, as seen in the illustrations, representative of action at Gallipoli in 1915.

Naval use

Periscopes allow a submarine, when submerged at a shallow depth, to search for targets and threats in the surrounding sea and air. When not in use, a submarine's periscope retracts into the hull. A submarine commander in tactical conditions must exercise discretion when using his periscope, since it creates a visible wake and may also become detectable by radar, giving away the sub's position.

The Frenchman Marie Davey built a simple, fixed naval periscope using mirrors in 1854. Thomas H. Doughty of the US Navy later invented a prismatic version for use in the American Civil War of 1861-1865.

The invention of the collapsible periscope for use in submarine warfare is usually credited[by whom?] to Simon Lake in 1902. Lake called his device the omniscope or skalomniscope. There is also a report[citation needed] that an Italian, Triulzi, demonstrated such a device in 1901, calling it a cleptoscope.

In another early example of naval use of periscopes, Captain Arthur Krebs adapted two on the experimental French submarine Gymnote in 1888 and 1889. Perhaps[original research?] the earliest example came in 1888 from the Spanish inventor Isaac Peral on his submarine Peral - developed in 1886 but launched on September 8, 1888. Peral's fixed, non-retractable periscope used a combination of prisms to rely the image to the submariner, but his submarine pioneered the ability to fire live torpedoes while submerged. Peral also developed a primitive gyroscope for his submarine navigation.[4]

As of 2009[update] modern submarine periscopes incorporate lenses for magnification and function as a telescope. They typically employ prisms and total internal reflection instead of mirrors, because prisms, which do not require coatings on the reflecting surface, are much more rugged than mirrors. They may have additional optical capabilities such as range-finding and targeting. The mechanical systems of submarine periscopes typically use hydraulics and need to be quite sturdy to withstand the drag through water. The periscope chassis may also be used to support a radio or radar antenna.

Submarines traditionally had two periscopes: a navigation or observation periscope and a targeting, or commander's, periscope. Early navies originally mounted these periscopes in the conning tower, one forward of the other in the narrow hulls of diesel-electric submarines. In the much wider hulls of recent[update] US Navy submarines, the two operate side-by-side. The observation scope, used to scan the sea surface and sky, typically had a wide field of view and no magnification or low-power magnification. The targeting or "attack" periscope, by comparison, had a narrower field of view and higher magnification. In World War II and earlier submarines it was the only means of gathering target data to accurately fire a torpedo, since sonar was not yet sufficiently advanced for this purpose (ranging with sonar required emission of an electronic "ping" that gave away the location of the submarine) and most torpedoes were unguided.

21st century submarines do not necessarily have periscopes. The United States Navy's Virginia-class submarines instead use photonics masts, pioneered by the Royal Navy's HMS Trenchant, which lift an electronic imaging sensor-set above the water. Signals from the sensor-set travel electronically to workstations in the submarine's control center. While the cables carrying the signal must penetrate the submarine's hull, they use a much smaller and more easily sealed—and therefore less expensive and safer—hull opening than those required by periscopes. Eliminating the telescoping tube running through the conning tower also allows greater freedom in designing the pressure hull and in placing internal equipment.

See also

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ First World War - Willmott, H.P.; Dorling Kindersley, 2003, Page 111

- ^ Not Only Enigma... Major Rudolf Gundlach (1892-1957) and His Invention), Warsaw-London, 1999

- ^ http://pedrocurto.com/1.html

External links

- The Fleet Type Submarine Online: Submarine Periscope Manual United States Navy Navpers 16165, June 1946

- Simulation of a Periscope at NTNUJAVA Virtual Physics Laboratory