Megalodon: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 375787436 by 86.28.255.117 (talk) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| name = Megalodon |

| name = Megalodon |

||

| fossil_range = [[Late Oligocene]]-[[Early Pleistocene]] {{Fossil range|25|1.6}} |

| fossil_range = [[Late Oligocene]]-[[Early Pleistocene]] {{Fossil range|25|1.6}} |

||

| image = |

| image = Megalodon shark jaws museum of natural history 068.jpg |

||

| image_width = 255px |

| image_width = 255px |

||

| image_caption = Real photo of Megalodon, taken by famous photographer [[Olivo Barbieri]]. |

| image_caption = Real photo of Megalodon, taken by famous photographer [[Olivo Barbieri]]. |

||

Revision as of 20:06, 27 July 2010

| Megalodon Temporal range: Late Oligocene-Early Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Real photo of Megalodon, taken by famous photographer Olivo Barbieri. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Disputed; Lamnidae or Otodontidae

|

| Genus: | Disputed; Carcharodon or Carcharocles

|

| Species: | †C. megalodon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Disputed; Carcharodon megalodon or Carcharocles megalodon For Carcharodon megalodon, Agassiz, 1843

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The megalodon (Template:Pron-en MEG-ə-lə-don, "big tooth" in Greek, from μέγας and ὀδούς) is an extinct megatoothed shark that existed in prehistoric times, from the Oligocene to Pleistocene epochs, approximately 25 to 1.6 million years ago.

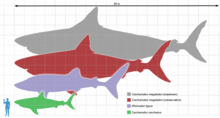

Paleontological research indicates that C. megalodon is among the largest and most powerful macro-predatory fishes in vertebrate history. C. megalodon is principally known from partially preserved skeletal remains, which indicate a shark of gigantic proportions — approaching a length of around 20.3 metres (67 ft). C. megalodon is widely regarded as the largest shark to have ever lived. After scrutiny of its remains, scientists have assigned C. megalodon to the order Lamniformes but its phylogeny is disputed. Scientists suggest that C. megalodon looked like a stockier version of the great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, in life. Fossil evidence confirms that C. megalodon had a cosmopolitan distribution. C. megalodon was a super-predator,[1] and bite marks on fossil bones of its victims indicate that it preyed upon large marine animals.

Discovery

Glossopetrae

According to Renaissance accounts, large, triangular fossil teeth often found embedded in rocky formations were once believed to be petrified tongues, or glossopetrae, of the dragons and snakes. This interpretation was corrected in 1667 by a Danish naturalist Nicolaus Steno, who recognized them as ancient shark teeth (and famously produced a depiction of a shark's head bearing such teeth).[2] He mentioned his findings in a book, The Head of a Shark Dissected, which also contained an illustration of a C. megalodon tooth, previously considered to be a tongue stone.[3]

Identification

A Swiss naturalist, Louis Agassiz, gave this shark its scientific name, Carcharodon megalodon, in 1835,[4] in his research work Recherches sur les poissons fossiles[5] (Research on fossil fish), which he completed in 1843. The teeth of the C. megalodon are morphologically similar to the teeth of the great white shark. On the basis of this observation, Agassiz assigned the genus Carcharodon to the megalodon.[4] While the scientific name is C. megalodon, it is often informally dubbed the megatooth shark [6] or giant white shark[7] or even monster shark.[8]

Fossils

As with all other sharks, the megalodon skeleton was formed of cartilage rather than bone; this results in mostly poorly preserved fossil specimens.[9]

Fossil teeth

The most common fossils of C. megalodon are its teeth, which are morphologically similar to the teeth of great white shark but are more robust,[6] and more regularly serrated.[6] The teeth of C. megalodon can measure over 180 millimetres (7.1 in) in slant height or diagonal length, and are the largest in size of any known shark species.[10]

Fossil vertebrae

Some partially preserved fossil vertebrae of C. megalodon have also been found.[3] The most notable example is a partially preserved but associated vertebral column of a single C. megalodon specimen excavated from Belgium in 1926. This specimen comprises 150 vertebral centra, with the largest centra being 155 mm in diameter.[6] However, the vertebral centra of C. megalodon can be over 225 mm in diameter,[11] and are the largest in size of any known shark species.

Fossil distribution and range

The fossils of C. megalodon have been excavated from many parts of the world, including Europe,[3] North America,[6] South America,[3][6] Puerto Rico,[12] Cuba,[13] Jamaica,[14] Australia,[15] New Zealand,[10] Japan,[3][6] Africa,[3][6] Malta,[10] Grenadines,[16] and India.[3] C. megalodon teeth have also been excavated from regions far away from continental lands (i.e. Mariana Trench in the Pacific).[10]

The earliest remains of C. megalodon have been reported from late Oligocene strata.[10][17] Although fossils of C. megalodon are predominantely absent in strata extending beyond the Tertiary boundary,[6] they have been reported from Pleistocene strata.[18] It is believed that C. megalodon became extinct in the Pleistocene probably about 1.5 million years ago.[9]

Physical anatomy

The great white shark is considered to be the closest extant analogue to C. megalodon.[3][6] The lack of exceptionally preserved fossil skeletons of C. megalodon have forced the scientists to rely on the morphology of the great white shark for the basis of its reconstruction and size estimation.[6]

Size estimation

Estimating the maximum size of C. megalodon is a highly controversial and difficult subject.[10] However, scientific community acknowledges that C. megalodon was larger than the whale shark, Rhincodon typus. The first attempt on reconstructing the jaw of this shark was made by Professor Bashford Dean in 1909. From the dimensions of this jaw reconstruction, the size of C. megalodon was theorized to be around 30 metres (98 ft), but in the light of new fossil discoveries and advances in vertebrate sciences, this jaw reconstruction is now considered to be inaccurate.[19] The major reason cited for this inaccuracy was that in Dean's time, the knowledge of C. megalodon's dentition was relatively poor.[19] Experts suggest that a rectified version of C. megalodon's jaw model by Bashford Dean would be about 70 percent of its original size and would depict a shark size consistent with modern findings.[19] Hence, to resolve such errors, scientists, aided by new fossil discoveries of C. megalodon and improved knowledge of its closest living analogue's anatomy, introduced more quantitative methods for estimating its size based on the statistical relationships between the tooth sizes and body lengths in the great white shark.[6][19]

Method proposed by John E. Randall

In 1973, the ichthyologist John E. Randall introduced a method to determine the size of the great white shark and extrapolated it to estimate the size of C. megalodon.[20] The proposed method is: "Megatooth's" Total Length in meters = [(0.096) × (enamel height of tooth in mm)].[19][20] The logic behind this method is that the enamel height (the vertical distance of the blade from the base of the enamel portion of the tooth to its tip) of the largest upper anterior tooth in the jaw of the shark can be used to determine its total length.[19] The largest C. megalodon tooth in his possession at that time had an enamel height of 120 mm,[19] which yielded 13 metres (43 ft) length.[19][20] However, two shark experts, Richard Ellis, and John E. McCosker, pointed out a flaw in Randall's method in 1991.[6] According to them, shark's tooth enamel height does not necessarily increase in proportion to the animal's total length. This observation led to proposals for new, more accurate methods to determine the size of the great white shark and similar sharks.[6]

Method proposed by Gottfried et al.

Three scientists, Michael D. Gottfried, Leonard J. V. Compagno and S. Curtis Bowman, after thorough research and scrutiny of many great white shark specimens, proposed a conservative but more accurate method for measuring the size of C. carcharias and C. megalodon that was published in 1996. The proposed method is: "Megatooth's" Total Length in meters = − (0.22) + (0.096) × [(Tooth maximum height in mm)].[6] The biggest C. megalodon tooth in the possession of this team was an upper anterior specimen, which had a maximum height of 168 mm (6.61 inch). This tooth was discovered by L. J. V. Compagno in 1993, and it yielded a length of 15.9 metres (52 ft).[6] However, rumors of larger C. megalodon teeth persisted at that time.[6] The maximum tooth height for this method is measured as a vertical line from the tip of the crown to the bottom of the lobes of the root, parallel to the long axis of the tooth.[6] In short words, the maximum height of the tooth is its slant height.[21]

Body mass estimation

Gottfried et al., also introduced a method to determine the body mass of the great white shark after studying the length – mass relationship data of 175 specimens at various growth stages and extrapolated it to estimate the body mass of C. megalodon. The proposed method is: Weight in kilogram = 3.29E−06[TL in (meters)3.174].[6] And according to this method, a 15.9 metres (52 ft) long specimen would have a body mass of about 47 metric tons (52 short tons).[6]

Method proposed by Clifford Jeremiah

In 2002, shark researcher Dr. Clifford Jeremiah also proposed a method to determine the size of great white shark and similar sharks (i.e., C. megalodon).[10] which is believed to be based on a sound principle that works well with most large sharks.[10] The proposed method is: "Shark's" Total Length in feet = [(Root width of an upper anterior tooth in cm) x (4.5)]. It translates as for every centimeter of root width of an upper anterior tooth, there is approximately 4.5 feet of the shark. Dr. C. Jeremiah asserts that the jaw perimeter of a shark is directly proportional to its total length, with the width of the roots of the largest teeth being a proxy for estimating jaw perimeter.[10] The largest tooth in the possession of Dr. C. Jeremiah had a root width of nearly 12 cm, which yielded 15.5 metres (51 ft) length.[10]

Maximum size and verdict

The existing fossil evidence indicates that C. megalodon likely exceeded 16 metres (52 ft) in total length.[10][22][23][24] In 1994, a marine biologist Patrick J. Schembri claimed that C. megalodon may have approached a maximum length of 25 metres (82 ft).[25] The early size estimation of C. megalodon was perhaps not far fetched. However, Gottfried et al., in 1996, proposed that C. megalodon could likely approach a maxima of 20.3 metres (67 ft) in total length.[6][23][24] The shark weight measuring technique suggested by the same team indicates that C. megalodon at this length would have a body mass of 103 metric tons (114 short tons).[6][23]

Hence, scientific research makes it clear that C. megalodon is the largest shark that has ever lived and is among the largest fish known to have existed.[6]

Dentition and Jaw Mechanics

A team of Japanese scientists, T. Uyeno, O. Sakamoto, and H. Sekine, discovered and excavated the partial remains of a C. megalodon, with nearly complete associated set of its teeth, from Saitama, Japan in 1989.[3] Another nearly complete associated C. megalodon dentition was excavated from Yorktown formations of Lee Creek, North Carolina in USA and served as the basis of a jaw reconstruction of C. megalodon in American Museum of Natural history in NYC.[6] These associated tooth sets solved the mystery of determining the exact number of teeth, which would be present in the jaws of the C. megalodon in each row in life. Hence, highly accurate jaw reconstructions were now possible. More associated dentitions of C. megalodon have also been found in later years. Based upon these discoveries, two scientists, S. Applegate and L. Espinosa, published an artificial dental formula (representation of dentition of an animal with respect to types of teeth and their arrangement within the animal's jaw) for C. megalodon in 1996.[3][6] Most accurate modern C. megalodon jaw reconstructions are based on this dental formula.

The dental formula of C. megalodon is: 2.1.7.43.0.8.4

As evident from the dental formula, C. megalodon contained four different kinds of teeth in its jaws.[3]

- Anterior - A

- Intermediate - I (In the case of C. megalodon, this tooth technically appears to be an upper anterior and is termed as "A3" because it is fairly symmetrical and does not points mesially (side of the tooth toward the midline of the jaws where left and right jaws meet), but this tooth is still designated as an intermediate tooth.[4] However, in the case of the great white shark, the intermediate tooth does point mesially. This point has often been raised in the Carcharodon vs. Carcharocles debate regarding the megalodon and favors the case of Carcharocles proponents.)

- Lateral - L

- Posterior - P

C. megalodon had a very robust dentition,[6] and it had a total of about 276 teeth in its jaws, spanning in 5 rows. (See "external links" below)

Paleontologists suggest that a very large C. megalodon had jaws over 2 metres (7 ft) across.[10]

Bite force

In 2008, a team of scientists led by Stephen Wroe have conducted an experiment to determine the bite force of the C. megalodon and results indicate that it was capable of exerting a bite force of around 182,000 newtons (N)[23] or 41,000 pound-force; over 28 times greater than that of Dunkleosteus at 6.3 kN (1,400 lbf), over 10 times greater than that of great white shark at 18 kN (4,100 lbf), over 5 times greater than that of T. rex at 31 kN (7,000 lbf), and also greater than that of Predator X at 150 kN (33,000 lbf).

Role of teeth

The exceptionally robust teeth of C. megalodon are serrated,[4][10] which would have improved efficiency in slicing the flesh of prey items. Paleontologist Dr. Bretton Kent suggests that these teeth are comparatively thicker for their size with much lower slenderness and bending strength ratios. They also have roots that are substantially larger relative to total tooth heights, and so have a greater mechanical advantage. Teeth with these traits are not just good cutting tools but also are well suited for grasping powerful prey and would seldom crack even when slicing through the bones.[26]

Skeletal anatomy

Aside from estimating the size of C. megalodon, Gottfried et al., also have tried to determine the schematics of the entire skeleton of C. megalodon.[6]

Jaw structure

To functionally support the very large and robust dentition, the jaws of the C. megalodon would have been massive, stouter, and more strongly developed than that of the great white shark, which possesses a somewhat gracile dentition in comparison.[6] The strongly developed jaws would have somewhat of a pig-eyed appearance.[6]

Chrondocranium

The chrondocranium of C. megalodon would have a blockier and more robust appearance than that of the great white shark, in order to functionally reflect its more massive jaws and dentition in comparison.[6]

Fins

The fins of C. megalodon would have been most likely proportionally larger and thicker in comparison to fins of great white shark because relatively larger fins were a necessity for propulsion and control of movements of such a massive shark.[6]

Axial skeleton

Through thorough scrutiny of the partially preserved vertebral C. megalodon specimen from Belgium, it became apparent that C. megalodon had a higher vertebral count than found in large specimens of any known shark.[6] Only the vertebral count in great white shark came close in quantity, symbolizing close anatomical ties between the two species.[6]

The complete skeleton

On the basis of the characteristics mentioned above, Gottfried and his colleagues eventually managed to reconstruct the entire skeleton of C. megalodon, which has been put on display in Calvert Marine Museum at Solomons island, Maryland in USA.[6][27][28] This C. megalodon skeletal reconstruction is 11.5 metres (38 ft) long and represents a young individual.[6] The team stresses that relative and proportional changes in the skeletal features of C. megalodon are ontogenetic in nature in comparison to that of great white shark, as they occur in great white sharks while growing larger.[6] In addition, the fossil remains of C. megalodon confirm that it had a heavily calcified skeleton in life.[11]

Paleoecological considerations

Prey relationships

Sharks are generally opportunistic predators. However, scientists propose that C. megalodon was "arguably the most formidable carnivore ever to have existed."[23] The factors — great size,[23] high-speed swimming capability,[28] and powerful jaws coupled with formidable killing apparatus,[23][6] ensured a super-predator with the capability to challenge a broad spectrum of fauna. Fossil evidence indicates that C. megalodon preyed upon cetaceans (i.e., whales,[3] including sperm whales,[10][29] bowhead whales,[7] cetotherrids,[9] squalodontids,[8][30] rorquals,[31] and Odobenocetops,[32] dolphins,[6] and porpoises[10]), sirenians,[30][33] pinnipeds,[9][16] and giant sea turtles.[30] Due to its size, C. megalodon would have fed primarily on large animals, and whales were likely important prey — many whale bones have been found with clear signs of large bite marks (deep gashes) made by the teeth that match those of C. megalodon,[3][6] and various excavations have revealed C. megalodon teeth lying close to the chewed remains of whales,[6][27] and sometimes in direct association with them.[34] Like other sharks, C. megalodon also would have been piscivorous.[9][28] C. megalodon likely also had a tendency for cannibalism.[35]

Hunting behavior

Sharks often employ complex hunting strategies to engage large prey animals. Some paleontologists suggest that the hunting strategies of the great white shark may offer clues as to how C. megalodon might have hunted its unusually large prey (i.e., whales).[8] However, fossil evidence suggests that C. megalodon employed more effective hunting strategies against large prey compared to the strategies employed by the great white shark.[26]

Paleontologists have conducted a survey of fossils to determine attacking patterns of C. megalodon on prey.[26] The findings suggest that the attack patterns could differ against prey with respect to its size.[8] Fossil remains of some small cetaceans suggest that they were likely rammed with great force from below before being killed and eaten.[8] One particular specimen — remains of a 9 metres (30 ft) long prehistoric baleen whale (unknown taxon from Miocene) provided the first opportunity to quantitatively analyze the attacking behavior of C. megalodon.[26] The predator primarily focused its attack on the tough bony portions (i.e. bony shoulders, flippers, rib cage, and upper spine) of the prey,[26] which great white sharks generally avoid.[26] Dr. Bretton Kent elaborated that C. megalodon attempted to crush the bones and damage delicate organs (i.e. heart, and lungs) harbored within the rib cage of the prey.[26] An attack on these essential body parts would have immobilized the prey and it would have died quickly due to massive internal injuries as a result.[26] These findings also clarify why the ancient shark needed more robust dentition than the great white shark's.[26]

During the Pliocene, larger and more advanced cetaceans appeared.[8] C. megalodon apparently further refined its hunting strategies to cope with these larger animals. Numerous fossilized flipper bones (i.e., segments of the pectoral fins), and caudal vertebrae of large whales from the Pliocene have been found with bite marks that were caused by attacks of C. megalodon.[6][23] This paleontological evidence suggests that C. megalodon would attempt to immobilize a large whale by ripping apart or biting off its propulsive structures before killing and feeding on it.[6][23]

Interspecific competition

C. megalodon faced a highly competitive environment during its time of existence. However, C. megalodon was likely one of the most powerful and dominant predators in vertebrate history,[23] and probably had a profound impact on the structuring of marine communities.[36] Paleontologist Robert Purdy found through a survey of fossils that other notable species of macro-predatory sharks (e.g. great white sharks) responded to competitive pressure from C. megalodon by avoiding regions it inhabited.[6] However, some contemporaneous macro-predatory odontocetes were likely among the chief predators of their time,[36] and may have presented tough competition.[8][37] Odontocetes may have generally functioned in pods for increased safety,[8][38] and some species likely employed co-ordinated hunting behaviour for greater competitive effectiveness.[39] However, paleontological evidence suggests that C. megalodon possessed the capability to compete with odontocetes of its time — bite marks on the fossil remains of odontocetes indicate a predator-prey relationship between giant macro-predatory sharks and these cetaceans.[30][29]

Range and habitat

C. megalodon was a pelagic fish that predominantly inhabited temperate and warm water environments. The fossil records of C. megalodon confirm that it was a cosmopolitan species.[10] Prior to the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, the oceans were relatively warmer.[40] This would have made it possible for the species to thrive in all the oceans of the world.

C. megalodon had enough behavioral flexibility to inhabit wide range of marine environments (i.e. coastal shallow waters,[30] coastal upwelling,[30] swampy coastal lagoons,[30] sandy littorals,[30] and offshore deep water environments[10]), and exhibited a transient life-style.[30] The adult C. megalodon were not abundant in shallow water environments,[30] and mostly lurked offshore.

Nursery areas

Fossil evidence suggests that the preferred nursery sites of C. megalodon were likely to have been warm water coastal environments, where potential threats were minor and food sources were plentiful.[22] As is the case with most sharks, C. megalodon also likely gave birth to live young. The size of the neonate C. megalodon teeth indicate that C. megalodon pups were around 2–3 metres (7–10 ft) in length at birth.[10][22] The young C. megalodon most likely preyed upon pinnipeds, fish, giant sea turtles, dugongs, and small cetaceans. Upon approaching maturity, C. megalodon predominantly preferred off-shore cetacean high-use areas and preyed upon large cetaceans.[6]

Extinction

It is not yet clear why C. megalodon became extinct after millions of years of dominance; however, several factors may have been involved.

Climatic cooling and ice ages

A major reason cited behind the extinction of C. megalodon is the decline in ocean temperatures at global scale.[8] The Isthmus of Panama closed around 5 million years ago and fundamentally changed global ocean circulation.[3][41] This geological event initially set the stage for glaciation in the northern hemisphere,[41] and later on, also facilitated cooling of the entire planet.[41] Consequently, during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene, there were ice ages,[42][43] which cooled the oceans significantly.[3] The cooling trend adversely impacted C. megalodon, as it preferred warmer waters.[3][6] Fossil evidence confirms the absence of C. megalodon in regions where water temperatures had significantly declined during the Pliocene.[6]

In addition, wide-scale glaciation during the Pliocene and Pleistocene tied up huge volumes of water in continental ice sheets, resulting in significant sea level drops.[40] Lower sea levels may have restricted many of the suitable warm water nursery sites for C. megalodon, hindering population maintenance. Nursery areas are pivotal for the survival of a species.[44]

Decline in food supply

Cetaceans attained their greatest diversity during the Miocene,[6] with over 20 recognized genera in comparison to only six living genera.[45] Such diversity presented an ideal setting to support a giant predator like C. megalodon.[6] However, the dependency of C. megalodon on large prey made it over-specialized.[27] In addition, during the Pliocene, many species of cetaceans became extinct,[46] and most surviving species disappeared from the tropics.[47] Whale migratory patterns during the Pliocene have been reconstructed from the fossil record, suggesting that most surviving species showed a trend towards polar regions.[40] The cooler water temperatures during the Pliocene cut C. megalodon off from polar regions, and large prey was effectively "no longer within the range" of C. megalodon after the migrations.[3][6][9][47] These developments diminished the food supply for C. megalodon in warm waters. Paleontologist Albert Sanders suggests that C. megalodon had become too large to sustain itself on the available food supply in the tropics.[44] In addition, the shortage of food sources in warm waters during the Pliocene and Pleistocene might have fueled cannibalism within C. megalodon.[8] The juvenile individuals were at increased risk from attacks by adult individuals during times of starvation.[8]

Evolution of the orca

The ancient relatives of the orca evolved during the Pliocene,[48] and some paleontologists have speculated that these odontocetes may also have contributed to the extinction of C. megalodon.[49] However, paleontologist Robert Purdy pointed out that there is not much fossil evidence for the history of marine vertebrates for the last three million years to support this hypothesis.[10] In addition, C. megalodon was already absent in high latitudes since early Pliocene due to cooling trend in oceans,[6] where ancient relatives of the orca commonly occurred.[48] Although competition may have occurred in other regions — bite marks on the fossil remains of dolphins have been observed,[6] which indicate a predator-prey relationship between C. megalodon and these cetaceans.[6] However, the relatively common occurrence of the ancient relatives of the orca in high latitudes during the Pliocene,[48] indicates the potential of these animals to cope with cold water temperatures. This capability likely favored their survival while C. megalodon was ill-fated.

Taxonomy

Even after decades of research and scrutiny, the controversy on phylogeny of C. megalodon still persists.[4][50] Several shark researchers (e.g. J. E. Randall, A. P. Klimley, D. G. Ainley, M. D. Gottfried, L. J. V. Compagno, S. C. Bowman, and R. W. Purdy) insist that C. megalodon is a close relative of the great white shark. However, several other shark researchers (e.g. D. S. Jordan, H. Hannibal, E. Casier, C. DeMuizon, T. J. DeVries, D. Ward, and H. Cappetta) dismiss the proposal that C. megalodon is a close relative of the great white shark, and cite convergent evolution as the reasons for the dental similarity. The arguments of the supporters of the Carcharocles genus for C. megalodon seem to have gained noticeable support.[27] However, the original taxonomic assignment still has wide-scale acceptance.[4]

Megalodon within Carcharodon

|

|

The traditional view is that C. megalodon should be classified within the genus Carcharodon along with the great white shark. Main reasons cited for this phylogeny are; (1) an ontogenetic gradation, whereby the teeth of C. carcharias shift from having coarse serrations as a juvenile to fine serrations as an adult, the latter resemble those of C. megalodon; (2) morphological similarity of teeth of young C. megalodon to those of C. carcharias; (3) a symmetrical second anterior tooth; (4) large intermediate tooth that is inclined mesially; and (5) upper anterior teeth that have a chevron-shaped neck area on the lingual surface. The supporters of classification as Carcharodon for C. megalodon suggest that C. megalodon and C. carcharias share a common ancestor, Palaeocarcharodon orientalis.[4][10]

Megalodon within Carcharocles

|

|

Around 1923, the genus Carcharocles was proposed by two shark researchers, D. S. Jordan and H. Hannibal, to classify a shark C. auriculatus. Later on, Carcharocles proponents assigned C. megalodon to Carcharocles genus.[4][10] Carcharocles proponents also suggest that the direct ancestor of the sharks belonging to the Carcharocles genus, is an ancient giant shark called Otodus obliquus, which lived during the Paleocene and Eocene epochs.[27][50] According to supporters of classification as Carcharocles for C. megalodon; Otodus obliquus evolved in to Carcharocles aksuaticus,[10][27] which evolved in to Carcharocles auriculatus,[10][27] which evolved into Carcharocles angustidens,[10][27] which evolved into Carcharocles chubutensis,[10][27] which eventually evolved into megalodon.[10][27] Hence, the immediate ancestor of C. megalodon is Carcharocles chubutensis,[10][27] because it serves as the missing link between Carcharocles augustidens and C. megalodon and it bridges the loss of the "lateral cusps" that characterize C. megalodon.[10][27]

Megalodon as chronospecies?

Shark researcher David Ward has further elaborated on the Carcharocles evolutionary process by implying that this lineage, stretching from the Paleocene to the Pliocene, is of a single giant shark which gradually changed through time, suggesting a case of chronospecies.[10]

New evolutionary position for great white shark

Carcharocles proponents point out that the great white shark is closely related to an ancient shark Isurus hastalis, the "broad tooth mako", rather than to C. megalodon.[4][51][52] One reason cited by paleontologist Dr. Chuck Ciampaglio is that the dental morphometrics (variations and changes in the physical form of objects) of I. hastalis and C. carcharias are remarkably similar.[4] Another reason cited is that C. megalodon teeth have much finer serrations than in C. carcharias teeth.[4] Further evidence linking the great white shark more closely to ancient mako sharks, rather than to C. megalodon, has been provided in 2009 — The fossilized remains of an ancient form of the great white shark were excavated from southwestern Peru in 1988, which are about 4 million years old. These fossilized remains demonstrate a likely shared ancestor of modern mako and great white sharks.[50][53]

Additional controversy

Paleontologist Dr. C. Ciampaglio asserts that similarities between the teeth of C. megalodon and the great white shark are superficial and there are noticeable morphometric differences between them, and these findings are sufficient to warrant a separate genus for C. megalodon.[8] However, some proponents of the Carcharodon genus for C. megalodon (i.e. M. D. Gottfried, and R. E. Fordyce) have provided more reasons to ascertain close relationship between the extinct megatooth sharks and the great white shark.[17] With respect to the recent controversy regarding fossil lamnid shark relationships, the overall morphology – particularly the internal calcification patterns – of the great white shark vertebral centra have been compared to well-preserved fossil centra from the megatooth sharks, including C. megalodon and C. angustidens. The close morphological similarity apparent from these comparisons provides supporting evidence for the idea that the giant fossil megatooth species are closely related to living white sharks.[17][54]

With respect to the case of the origins of the great white shark, M. D. Gottfried, and R. E. Fordyce have pointed out that some great white shark fossils are about 16 million years old and predate the transitional Pliocene fossils.[17] In addition, the Oligocene records of C. megalodon,[10][17] contradict with the suggestion that Carcharocles chubutensis is the immediate ancestor of the C. megalodon. These records also indicate that C. megalodon actually co-existed with Carcharocles angustidens.[17] Hence, proponents for the Carcharodon genus for C. megalodon argue that extinct megatoothed sharks should be placed within the genus Carcharodon.[17]

Some paleontologists argue that the Otodus genus should be used for sharks within the Carcharocles lineage and the Carcharocles genus should be discarded.[22]

At present, Carcharocles proponents accept that both species belong to the order Lamniformes, and in the absence of living members of the family Otodontidae, great white shark should be regarded as ecologically analogous species to C. megalodon.[22]

In fiction

Ever since the remains of C. megalodon were discovered, it has been an object of fascination. It has been portrayed in several works of fiction, including films and novels, and continues to hold its place among the most popular subjects for fictional works involving Sea Monsters. Many of these works of fiction posit that at least a relict population of C. megalodon actually survived extinction and lurk in the depths of the ocean, and individuals may manage to surface from the vast depths, either as a result of human intervention or through natural means. Jim Shepard's story "Tedford and the Megalodon" is a good example of this. Such beliefs are usually inspired by discovery and excavation of a C. megalodon tooth by HMS Challenger in 1872, which some believed to be only 10,000 years old.[55] This tooth has been re-examined and findings indicate that it is actually untestable for age.[55]

Some works of fiction (such as Shark Attack 3: Megalodon and Steve Alten's Meg series) incorrectly depict Megalodon as being a species over 70 million years old and to have been alive at the time of Dinosaurs. The writers of the movie Shark Attack 3: Megalodon depicted this assumption by referring to and using an altered copy of a book by shark researcher, Richard Ellis, called "Great White Shark". The altered copy had several pages that don't exist in the real book. The author of the original book sued the film's distributor Lions Gate Entertainment, asking for a halt to the film's distribution along with $150,000 in damages.[56] Steve Alten's Meg: A Novel of Deep Terror is probably best known for portraying this inaccuracy with its prologue and cover artworks depicting a Megalodon killing a Tyrannosaurus rex in the sea.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Compagno, Leonard J. V. (May 1989). "Copyright: Alternative life-history styles of cartilaginous fishes in time and space". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 28: 33–75. doi:10.1007/BF00751027.

- ^ Haven, Kendall (1997). 100 Greatest Science Discoveries of All Time. Libraries Unlimited. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1591582652.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Bruner, John (1997). "The "Megatooth" shark, Carcharodon megalodon". Mundo Marino Revista Internacional de Vida Marina.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Nyberg K.G, Ciampaglio C.N, Wray G.A (2006). "Tracing the ancestry of the GREAT WHITE SHARK". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 806–814. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[806:TTAOTG]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|DUPLICATE DATA: year=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Agassiz, Louis (1833–1843). Recherches sur les poissons fossiles ... / par Louis Agassiz. Neuchatel :Petitpierre. p. 41. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az Klimley, Peter; Ainley, David (1996). Great White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Academic Press. ISBN 0124150314.

- ^ a b deGruy, Michael (2006). Perfect Shark (TV-Series). BBC.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|country=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Narrated by: Robert Leigh (2009-04-27). "Monster Shark". Prehistoric Predators. National Geographic.

{{cite episode}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c d e f Roesch, Ben (1998). "The Cryptozoology Review: A Critical Evaluation of the Supposed Contemporary Existence of Carcharocles Megalodon".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Renz, Mark (2002). Megalodon: Hunting the Hunter. PaleoPress. ISBN 0-9719477-0-8.

- ^ a b Bendix-Almgreen, Svend Erik (November 15, 1983). "Carcharodon megalodon from the Upper Miocene of Denmark, with comments on elasmobranch tooth enameloid: coronoi'n" (PDF). Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark. 32. Copenhagen: Geologisk Museum: 1–32. Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nieves-Rivera, Angel M. (2003). "New Record of the Lamnid Shark Carcharodon megalodon from the Middle Miocene of Puerto Rico". Caribbean Journal of Science. 39: 223–227.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Iturralde-Vinent, M. (1996). "CATALOG OF CUBAN FOSSIL ELASMOBRANCHII (PALEOCENE--PLIOCENE) AND PALEOOCEANOGRAPHIC IMPLICATIONS OF THEIR LOWER--MIDDLE MIOCENE OCCURRENCE" (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Jamaicana de Geología. 31. Cuba: 7–21. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Donovan, Stephen; Gavin, Gunter (2001). "Fossil sharks from Jamaica" (PDF). 28. Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum: 211–215.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fitzgerald, Erich (2004). "A review of the Tertiary fossil Cetacea (Mammalia) localities in Australia" (PDF). Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 61 (2). Australia: Museum Victoria: 183–208. ISSN 1447-2554. Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Portell, Roger; Hubell, Gordon; Donovan, Stephen; Green, Jeremy; Harper, David; Pickerill, Ron (2008). "Miocene sharks in the Kendeace and Grand Bay formations of Carriacou, The Grenadines, Lesser Antilles" (PDF). 44 (3). Caribbean Journal of Science: 279–286.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Gottfried M.D., Fordyce R.E. (2001). "An Associated Specimen of CARCHARODON ANGUSTIDENS (CHONDRICHTHYES, LAMNIDAE) From the LATE OLIGOCENE of NEW ZEALAND, with comments on CARCHARODON Interrelationships". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (4): 730–739. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0730:AASOCA]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Brown, Robin (2008). Florida's Fossils. Pineapple Press. ISBN 978-1-56164-409-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Helfman, Gene; Collette, Bruce; Facey, Douglas (1997). The diversity of fishes. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-8654-2256-8.

- ^ a b c Randall, John (July 1973). "Size of the Great White Shark (Carcharodon)". Science Magazine: 169–170.

- ^ Kowinsky, Jayson (2002). "The Size of Megalodons". Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ a b c d e Pimiento, Catalina (May 10, 2010). "Ancient Nursery Area for the Extinct Giant Shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama". PLoS One. 5 (5). Panama: PLoS.org: e10552. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010552. PMC 2866656. PMID 20479893. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wroe, S. (2008). "Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite?" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 276 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00494.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Compagno, Leonard J. V. (2002). SHARKS OF THE WORLD: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. p. 97. ISBN 9251045437.

- ^ Schembri, Patrick (1994). "MALTA'S NATURAL HERITAGE" (PDF). Natural Heritage. in. MALTA: University of MALTA: 105–124. Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Riordon, James (June 1999). "Hell's teeth". NewScientist Magazine (2190): 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Andres, Lutz (2002). "C. megalodon — Megatooth Shark, Carcharodon versus Carcharocles". Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Caroline (2000). Giant Shark: Megalodon, Prehistoric Super Predator. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9780395914199.

- ^ a b "MEGALODON". Fossil Farm Museum Of The Fingerlakes. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Aguilera O., Augilera E. R. D. (2004). "Giant-toothed White Sharks and Wide-toothed Mako (Lamnidae) from the Venezuela Neogene: Their Role in the Caribbean, Shallow-water Fish Assemblage". Caribbean Journal of Science. 40 (3): 362–368.

- ^ Godfrey, Stephen (April 2004). "The Ecphora: Fascinating Fossil Finds" (PDF). Paleontology Topics. Calvert Marine Museum. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ "Fact File: Odobenocetops". BBC. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Godfrey, Stephen (March 2007). "The Ecphora: Shark-Bitten Sea Cow Rib" (PDF). Paleontology Topics. Calvert Marine Museum. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Orangel, A. A. ; Garcia, L. ; Cozzuol, A. M. (2008). "Giant-toothed white sharks and cetacean trophic interaction from the Pliocene Caribbean Paraguaná Formation". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 82 (2): 204–208. doi:10.1007/BF02988410.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tanke, Darren; Currie, Philip (December 1998). "Head-Biting Behaviour in Theropod Dinosaurs: Paleopathological Evidence" (PDF). Gaia 15: 168. ISSN 0871-5424.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Lambert, Olivier (1 July 2010). "The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru". Nature. 466 (7302). Peru: 105–108. doi:10.1038/nature09067. PMID 20596020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "New Leviathan Whale Was Prehistoric "Jaws"?". National Geographic Daily News. Peru: National Geographic. 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Ancient monster whale more fearsome than Moby Dick". NewScientist. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Bianucci, Giovanni; Walter, Landini (8 Sep 2006). "Killer sperm whale: a new basal physeteroid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Late Miocene of Italy". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 148 (1): 103–131. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00228.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Gillette, Lynett. "Winds of Change". San Diego Natural History Museum. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ^ a b c "How the Isthmus of Panama Put Ice in the Arctic". 2004-03-22. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ "Pliocene epoch". Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ "Pleistocene epoch". Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ a b Reilly, Michael (29 September 2009). "Prehistoric Shark Nursery Spawned Giants". USA: Discovery News.

- ^ Dooly A.C, Nicholas C.F, Luo Z.X (2004). "The Earliest known member of the RORQUAL" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 453–463. doi:10.1671/2401. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|DUPLICATE DATA: year=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fordyce, R. Ewan (2002). "Australodelphis mirus, a bizarre new toothless ziphiid-like fossil dolphin (Cetacea: Delphinidae) from the Pliocene of Vestfold Hills, East Antarctica". Antarctic Science. 14 (1). Cambridge University Press: 37–54. doi:10.1017/S0954102002000561.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Allmon, Warren D. (2006). "Late Neogene Oceanographic Change along Florida's West Coast: Evidence and Mechanisms". The Journal of Geology. 104 (2). USA: The University of Chicago: 143–162. doi:10.1086/629811.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Heyning, John; Dahlheim, Marilyn (15 January 1988). "Mammalian Species: Orcinus Orca" (PDF). The American Society of Mammalogists. 304: 1–9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Turner, Pamela S. (Oct/Nov 2004). "Showdown at Sea: What happens when great white sharks go fin-to-fin with killer whales?". National Wildlife. 42 (6). National Wildlife Federation. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Ehret D. J., Hubbell G., Macfadden B. J. (2009). "Exceptional preservation of the white shark CARCHARODON from the early Pliocene of PERU". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1671/039.029.0113.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bowling, Stuart (1997). "C. Megalodon".

- ^ Alter, Steven (2001). "Origin of the Modern Great White Shark". Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Dell-Amore, Christine (2009). "Most Complete Great White Fossil Yet". Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Godfrey, Stephen (November 11, 2006). "The Geology and Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs" (PDF). Paleontology Topics. The Ecphora Miscellaneous Publications. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Mega Jaws". MonsterQuest. Season 3. Episode 7. March 18, 2009.

- ^ Boniello, Kathianne (2009-07-12). "Shark Film has Writer Biting Mad". New York Post.

References

- Bretton W. Kent (1994). Fossil Sharks of the Chesapeake Bay Region. Egan Rees & Boyer, Inc. 146 pages. ISBN 1881620018

- Shimada K (2003). The relationship between the tooth size and total body length in the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias (Lamniformes: Lamnidae). J Fossil Res 35: 28–33.

- K. A. Dickson, and J. B. Graham (2004). Evolution and consequences of endothermy in fishes. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 77(6): 998-1018. doi:10.1086/423743

External links

- Ancient Shark's Bite More Powerful Than T. Rex's from LiveScience

- Carcharocles: Extinct Megatoothed shark

- Fossil Field Guide, Carcharocles Megalodon from San Diego Natural History Museum

- Fact File: Megalodon from BBC, with pictures and video

- Prehistoric Megalodon Information

- Quick Facts about Megalodon: Largest Shark That Ever Lived!

- The largest modern Megalodon jaw reconstruction in the world

- Shark Tales featuring Megalodon with demonstration of the chewing action of the giant shark by Dr. Chuck Ciampaglio

- Jurassic Shark

- 3-D image of Great White Shark compared to Megalodon

- Prehistoric Jaws killed whales with single bite by Steve Farrar, science correspondent

Paleontological videos

NOTE: Flash Player is required to view the content below.

- A video clip of the Perfect Shark (2006) show from BBC (Presents fossil evidence of predator-prey relationships of Megalodon)

- Video Gallery containing video clips featuring Megalodon from Discovery Channel

- Paleontologist Mark Renz shows a huge Megalodon tooth (one of the largest ever discovered) on YouTube

- A video clip depicting aggressive interspecific interactions between Megalodon and a pod of killer odontoceti (B. shigensis) from History Channel

- Animated size comparison of Megalodon with great white shark, human, and school bus from North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences on YouTube.

- Prehistoric Washington DC: Mega Shark from Discovery Channel (Depicts attacking strategies of Megalodon on prey)

- Shark Week Special on Megalodon with Pat McCarthy and John Babiarz on YouTube with comments on its extinction.