Lizzie Borden: Difference between revisions

→Public reaction: simplified sentence |

→Public reaction: reworded |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

:: She gave her father forty-one. |

:: She gave her father forty-one. |

||

The anonymous rhyme was made up by a writer as a tune to sell newspapers{{Citation needed|date=October 2010}} even though in reality Borden's stepmother suffered 18<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/notorious_murders/famous/borden/index_1.html |title=Lizzie Borden Took An Ax |work=[[Crime Library]] |accessdate=November 21, 2008}}</ref> or 19<ref name="straight">{{cite web|last=Adams |first=Cecil |url=http://www.straightdope.com/mailbag/mlizzieborden.html |title=Did Lizzie Borden kill her parents with an axe because she was discovered having an affair? |work=[[The Straight Dope]] |date=March 13, 2001 |accessdate=November 21, 2008}}</ref> blows to her person and her father only 11. Even though she was acquitted, Borden was ostracized by neighbors after the trial.<ref name="straight" /> Lizzie Borden's name was again brought |

The anonymous rhyme was made up by a writer as a tune to sell newspapers{{Citation needed|date=October 2010}} even though in reality Borden's stepmother suffered 18<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/notorious_murders/famous/borden/index_1.html |title=Lizzie Borden Took An Ax |work=[[Crime Library]] |accessdate=November 21, 2008}}</ref> or 19<ref name="straight">{{cite web|last=Adams |first=Cecil |url=http://www.straightdope.com/mailbag/mlizzieborden.html |title=Did Lizzie Borden kill her parents with an axe because she was discovered having an affair? |work=[[The Straight Dope]] |date=March 13, 2001 |accessdate=November 21, 2008}}</ref> blows to her person and her father only 11. Even though she was acquitted, Borden was ostracized by neighbors after the trial.<ref name="straight" /> Lizzie Borden's name was again brought into the public eye when she was accused of [[shoplifting]] in 1897.<ref name="dates">{{cite web|url=http://www.lizzieborden.org/bordendates.htm |title=Dates in the Borden Case |accessdate=June 13, 2008 |publisher=[[Fall River Historical Society]]}}{{dead link|date=September 2010}}</ref> |

||

==Genealogy== |

==Genealogy== |

||

Revision as of 15:48, 15 October 2010

Lizzie Borden | |

|---|---|

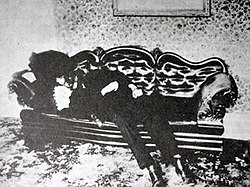

Lizzie Borden, circa 1889 | |

| Born | Lizzie Andrew Borden July 19, 1860 |

| Died | June 1, 1927 (aged 66) |

| Resting place | Oak Grove Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Murder trial defendant |

| Parent(s) | Andrew Jackson Borden (1822–1892) Sarah Anthony Morse (1823–1863), mother Abby Durfee Gray (1828–1892), stepmother |

| Relatives | Emma Lenora Borden (1851–1927), sister Alice Esther Borden (1856–1858), sister John Vinnicum Morse, uncle |

Lizzie Andrew Borden[2] (July 19, 1860 – June 1, 1927) was a New England spinster who was the central figure in the hatchet murders of her father and stepmother on August 4, 1892 in Fall River, Massachusetts in the United States. The murders, subsequent trial, and ensuing trial by media became a cause célèbre. The fame of the incident has endured in American pop culture and criminology. Although Lizzie Borden was acquitted, no one else was ever arrested or tried, and she has remained a notorious figure in American folklore. Dispute over the identity of the killer or killers continues to this day.

Murders

On August 4, 1892, Andrew Borden had gone into Fall River to do his usual rounds at the bank and post office. He returned home at about 10:45 a.m.; Lizzie Borden found his body about thirty minutes later.

During the murder trial, the Borden's twenty-six year old maid, Bridget Sullivan, testified that she was lying down in her room on the third floor of the house shortly after 11:00 a.m. when she heard Lizzie call to her, saying someone had killed her father; his body was found slumped on a couch in the downstairs sitting room. Andrew Borden's face was turned to the right hand side, apparently at ease, as if he was asleep.[3]

Shortly thereafter, while Lizzie Borden was being tended by neighbors and the family doctor, Sullivan discovered the body of Abby Borden in the guest bedroom located upstairs. Both Andrew and Abby Borden had been killed by crushing blows to their skulls from a hatchet. Andrew Borden's left eyeball was cleanly split in two.[4]

Motive and methods

Over a period of years after the death of Sarah Borden, life in the Borden home had grown unpleasant with affection between the older and younger family members waning. Andrew was known by family, friends, and business associates as tight-fisted and generally rejected modern conveniences. The family still threw their excrement buckets (slops) onto the backyard. The two daughters, well past marriage age, gladly entered the modern world whenever they visited friends. Emma and Lizzie had no marketable skills, and their father did not seem concerned about their future. His plan to sell the farm in Swansea was seen as the beginning of the end.[5]

The barn behind the home did not see much use after Andrew sold the horse. Lizzie had some pigeons in cages on the second floor that she fed and watered. She arrived one day to find the pigeons laying on the ground with their heads chopped off with a hatchet. Andrew said he killed them because the birds were attracting young boys in the neighborhood to the barn, and he felt they might get hurt or start a fire.

The upstairs floor of the house was divided. The front was occupied by the Borden sisters, while the rear was occupied by Andrew and Abby. Meals were seldom eaten together. Conflict had increased between the two daughters and their father about his decision to divide the valuable properties among relatives before his death. Relatives of their stepmother had been given a house, and John Morse, brother to the deceased Sarah Borden, had come to visit the week of the murders. His visit was to facilitate transfer of farm property, which included what had been a summer home for the Borden daughters. Shortly before the murders, a major argument had occurred which resulted in both sisters leaving home on extended "vacations". Lizzie Borden, however, decided to end her trip early and returned home.

Borden had attempted to purchase prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) from local druggist Eli Bence, but Bence refused. Borden claimed she planned to use it it to clean a seal skin cloak;[6] the defense argued that this incident was not admissable evidence.

Shortly before the murders, the entire household became violently ill. As Mr. Borden was not a popular man in Fall River, Abby feared they were being intentionally poisoned. The family doctor, however, diagnosed their illness as food poisoning. Andrew Borden had purchased cheap mutton for the family to eat, and they left it on the stove for days, used for multiple meals. The family believed the milk was being tainted by someone; after the murders, the milk was tested but nothing was found that could be connected to their illness. Both murder victims had their stomachs removed in an autopsy performed on the Borden dining room table the day of their deaths. The stomachs, with their contents, were sent to Harvard medical school to be examined for toxins; nothing was found.[7]

The trial

Lizzie Borden was arrested and jailed on August 11, 1892, with her trial beginning ten months later in New Bedford, Massachusetts.[7] Her stories proved to be inconsistent, and her behavior suspect. She was tried for the murders and was defended by former Massachusetts Governor George D. Robinson and Andrew V. Jennings.[5] One of the prosecutors in the trial was William H. Moody, a future United States Attorney General and Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

During the police investigation, a hatchet was found in the basement and was assumed to be the murder weapon.[5] Though it was clean, most of its handle was missing and the prosecution stated that it had been broken off because it was covered with blood. Police officer Michael Mullaly testified that he found the head of the hatchet next to a hatchet handle; Deputy Marshall John Fleet contradicted this testimony. Later, a forensics expert said there was no time for the hatchet to be cleaned after the murder.[8] The prosecution was hampered by the fact that the Fall River police did not put credence in the then-new forensic technology of fingerprinting, and refused to take prints from the hatchet.[9]

No blood-soaked clothing was found as evidence by police. A few days after the murder, Borden tore apart and burned a blue dress in the kitchen stove, claiming she had brushed against fresh baseboard paint which had smeared on it.[5]

Despite incriminating evidence and testimony presented by the prosecution, Lizzie Borden was acquitted on June 20, 1893 after the jury deliberated only an hour and a half.[5] The fact that no murder weapon was found and no blood evidence was noted just a few minutes after the second murder pointed to reasonable doubt. Her entire original inquest testimony [10] was barred from the trial. Also excluded was testimony regarding her attempt to purchase prussic acid.[6] Adding to the doubt was another axe murder which took place shortly before the trial and was perpetrated by a man named José Correira. While many of the details in both murders were similar, Correira was proven to be out of the country when the Borden murder took place.[11]

After the trial, the Borden sisters moved to a new house that Lizzie christened Maplecroft,[5] located on French Street, then a fashionable neighborhood in Fall River. The large home included indoor plumbing and private bathrooms. The sisters settled all claims against them from Abby's side of the family, giving Abby Borden's family members everything they wanted in order to avoid further lawsuits. Because it was proven that Abby died before Andrew, all of her estate legally went to Andrew, with Andrew's estate going to his daughters. The settlement reached between the Borden sisters and Abby's two sisters was substantial.[7][12]

In June 1905, after twelve years, the Borden sisters became estranged over differences in their lifestyles. Shortly after arguing over a party Lizzie had given for Nance O'Neil and her theater friends,[13] Emma moved out of the house to live with her close friend Alice Lydia Buck. After the separation from her sister Emma, Lizzie Borden began using the name "Lizbeth A. Borden", rather than "Lizzie".[7][12]

Death

Following the surgical removal of her gallbladder, Lizzie Borden was ill the last year of her life. Her private staff was the sole witnesses to her decline. Borden died of pneumonia on June 1, 1927 in Fall River, Massachusetts.[14] Borden's funeral details were not made public and few people attended her burial.[15] Borden was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery under the name "Lizbeth Andrew Borden", her footstone was inscribed "Lizbeth".[16] Borden had never married, and her will, probated from June 25, 1927 through March 24, 1933, left $30,000 to the Fall River Animal Rescue League.[17][18] She also left $500 in perpetual trust for the care of her father's grave. Much of her wealth was transferred to her cousin Grace H. Howe, and her closest friend Helen Leighton. The final probate in 1933 gave them almost $6000 each in the middle of the Great Depression.[1]

Nine days later, on June 10, 1927,[16] her sister Emma died from chronic nephritis[19] in the home she shared with her friend and nurse Annie C. Connor, located in Newmarket, New Hampshire. She moved there due to the infirmities of old age, and to get away from the notoriety brought on by a new book about the murders.

The house on Second Street where the murders were committed is currently a bed and breakfast.[20] Maplecroft, Borden's mansion on French Street, is a privately owned residence.[citation needed]

Conjecture

Several theories have been presented over the years suggesting Lizzie Borden may not have committed the murders, and that other suspects may have had motives. One theory is that the Borden's maid, Bridget Sullivan, actually committed the murders; This theory suggests that Sullivan was angry with the Bordens for being asked to clean the windows, a taxing job on a hot day, and just one day after having suffered from food poisoning.[21] Another potential suspect was suggested by Arnold R. Brown in his work, Lizzie Borden: The Legend, The Truth, The Final Chapter. In his book, Brown theorizes that the murderer was the illegitimate paternal half-brother of Lizzie, William Borden. Brown believes that Lizzie's half brother committed the murders out of revenge following his failed efforts to extort money from his father, Andrew Borden.

Yet another theory is that Borden suffered petit mal seizures during her menstrual cycle. During these seizures, Borden was known to enter a fugue state which, as this theory suggests, would have allowed her to unknowingly commit the murders.[22]

Nance O'Neil

Two Lizzie Borden biographers, Evan Hunter and David Rehak, contend that Lizzie Borden had an intimate affair with actress Nance O'Neil, whom she met in Boston in 1904.[23] The pair got along well, despite Borden's notoriety.[13] The relationship was cited as the cause of Emma Borden's final separation from her sister.[13]

O'Neil was later portrayed as a character in a musical about Borden, entitled Lizzie Borden: A Musical Tragedy in Two Axe. Actress Suellen Vance originated the role.[24]

Public reaction

The trial received a tremendous amount of national publicity. It has been compared to the later trials of Bruno Hauptmann, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg and O.J. Simpson as a landmark in media coverage of legal proceedings.[25][26][27][28][29][30]

The case was memorialized in a popular skipping-rope rhyme:[31]

- Lizzie Borden took an axe

- And gave her mother forty whacks.

- When she saw what she had done

- She gave her father forty-one.

The anonymous rhyme was made up by a writer as a tune to sell newspapers[citation needed] even though in reality Borden's stepmother suffered 18[32] or 19[8] blows to her person and her father only 11. Even though she was acquitted, Borden was ostracized by neighbors after the trial.[8] Lizzie Borden's name was again brought into the public eye when she was accused of shoplifting in 1897.[16]

Genealogy

Andrew Jackson Borden, married Sarah Anthony Morse on December 25, 1845. They had three children: Emma Lenora 1851, Alice Esther 1856, and Lizzie Andrew 1860. Alice Esther died in 1858. Sarah Anthony Borden died in 1863. Andrew's second wife was Abby Durfee Gray, and they were married on June 6, 1865. Andrew and Abby died in 1892, and Emma and Lizzie died in 1927. They are all buried in the Borden Family Plot in Oak Grove Cemetery.

Borden was a distant relative of the American milk processor Gail Borden (1801–1874) and Robert Borden (1854–1937), Canada's Prime Minister during World War I.[33]

Lizzie Borden and actress Elizabeth Montgomery, who coincidentally portrayed Borden in a television movie about the murders and trial, were sixth cousins once removed. Both women descended from 17th-century Massachusetts resident John Luther. Rhonda McClure, the genealogist who documented the Montgomery-Borden connection, said, "I wonder how Elizabeth would have felt if she knew she was playing her own cousin."[34]

Borden and culture

Publication

- A regularly published newsletter: The Lizzie Borden Quarterly featured a comic strip titled Princess Maplecroft.[citation needed]

Radio

- The radio anthology series Suspense aired adaptations of the Borden story twice, once as "The Fall River Tragedy" on January 14, 1952, [citation needed] and once as "Goodbye, Miss Lizzie Borden" on October 4, 1955. [citation needed] Other radio adaptations include "Crime Classics: The Bloody Bloody Banks Of Fall River" from 1953, CBS radio's "Second Look At Murder", and "Unsolved Mysteries: Lizzie Borden". [citation needed]

Television and film

- An episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents entitled "The Older Sister" retold the Borden story, in which Emma had murdered her parents due to a mental illness she suffered, while Lizzie covered for her.[citation needed]

- Armstrong Circle Theatre, Season 12, Episode 1, "Legend of Murder – The Untold Story of Lizzie Borden" (first aired October 11, 1961), was a dramatization of Edward D. Radin's book Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story (Simon and Schuster, 1961), which put forth the theory that Bridget Sullivan was the actual murderess. Lizzie was played by Clarice Blackburn and Bridget by Mary Doyle. [citation needed]

- Elizabeth Montgomery depicted Borden in William Bast's two hour television movie, The Legend of Lizzie Borden (1975). In the movie, Lizzie Borden performs the murders in the nude (thus explaining the lack of bloodstained clothing). [citation needed]

- The Sci-Fi Channel Ghost Hunters "TAPS" team investigated the Lizzie Borden house for paranormal activity in episode 12 of season 2. [citation needed]

- On January 23, 2007, the Crime & Investigation Network aired a documentary on the Lizzie Borden story.[citation needed]

- In 2004, the Discovery Channel aired an investigative documentary called Lizzie Borden Had an Axe. In the episode, a pair of detectives used modern forensics to exonerate Sullivan and prove Lizzie could have been the killer. [citation needed]

- In 2008, The History Channel's series MonsterQuest visited the Borden home looking for ghosts. [citation needed]

- The Travel Channel's show Scariest Places on Earth featured the Borden home as the #1 most scary place on earth. [citation needed]

- The movie "Monkeybone" shows Lizzie Borden in a cell for coma-stricken people whose bodies have been stolen by their alter-ego upon awakening and gone out to cause nightmares. [citation needed]

- Lizzie Borden's compact is an artifact from the Syfy series "Warehouse 13". Opening it and looking in the mirror makes you enter a dream state where you try to kill the ones you love. [citation needed]

Theatre

- The choreographer Agnes de Mille created a ballet on the life of Lizzie Borden in 1948, entitled Fall River Legend.[35]

- The anthology of short plays, "Sepia and Song", contained a play called "A Memory of Lizzie," with scenes from Lizzie Borden's childhood interpersed with quotes from her trial.[36]

- Blood Relations by Sharon Pollock premiered at Theatre Tree, Edmonton Canada in 1980. The play is set in 1902, with its "dream thesis" set in 1892, at Fall River, Massachusetts. It explores the events leading up to the trial.[citation needed]

- The Testimony of Lizzie Borden by Eric Stedman, a docudrama staged in an accurate reproduction of the Borden sitting room which re-created much of Lizzie's actual inquest testimony, premiered at Theatre on the Towpath in New Hope, Pa. in 1994 and was presented in Fall River in 1995.[citation needed]

- Lizzie Borden's Tempest by Brendan Byrnes played the New York International Fringe Festival in 1998. As Lizzie reads the role of Miranda in The Tempest with her local theatre club, Shakespeare's storm resurrects and reunites the Borden Family. The play's central idea is based on an actual program displayed at the Fall River Historical Society that lists a "Miss Borden" playing the role of Miranda in The Tempest.[citation needed]

Citations

- ^ a b "Bequest for Tomb of Slain Father" (fee required). The New York Times. June 8, 1927. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ "Inquest Testimony of Lizzie Borden". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

Q. Give me your full name. A Lizzie Andrew Borden. Q. Is it Lizzie or Elizabeth? A Lizzie. Q. You were so christened? A I was so christened.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 27 (help) - ^ "Testimony of Bridget Sullivan in the Trial of Lizzie Borden". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law: Famous Trials. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ Porter, Edwin H. (1893). The Fall River Tragedy: A History of the Borden Murders. Fall River: Press of J.D. Munroe. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Linder, Doug. "The Trial of Lizzie Borden". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law: Famous Trials. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ a b "Prussic Acid In The Case". New York Times. June 15, 1893. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Cantwell, Mary (July 26, 1992). "Lizzie Borden Took an Ax". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c Adams, Cecil (March 13, 2001). "Did Lizzie Borden kill her parents with an axe because she was discovered having an affair?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ "On this day in crime history." The Washington, D.C. Examiner. August 4, 2008.

- ^ http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/LizzieBorden/bordeninquest.html

- ^ Noe, Denise (1999). "The Murderer Who Inadvertently Helped Miss Lizzie". The Lizzie Borden Quarterly: 8. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Cast of Characters". LizzieAndrewBorden.com. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Sisters Estranged Over Nance O'Neill". The San Francisco Call. June 7, 1905. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ "Lizzie Borden Dies" (fee required). The New York Times. June 3, 1927. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ "Few at Borden Burial" (fee required). The New York Times. June 6, 1927. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Dates in the Borden Case". Fall River Historical Society. Retrieved June 13, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Lizzie Borden's Will Is Probated". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 25, 1927.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Lizzie Borden's Last Will and Probate Records" (PDF). Lizzieandrewborden.com. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ The Cases That Haunt Us. books.google.com. 2001. ISBN 9780743212397. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast". Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ Kent, David (1992). "4". Forty Whacks: New Evidence in the Life and Legend of Lizzie Borden (1 ed.). Emmaus, PA: Yankee Books. p. 39. ISBN 0899093515.

- ^ Lincoln, Victoria (1967). "1". A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight (Book Club ed.). New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 44–60. ISBN 0930330358.

- ^ Rehak, David (2005) Did Lizzie Borden Axe for It? (1 ed.); Just My Best Publishing; pp. 67-69. ISBN 1450550185

- ^ http://www.suellenvance.com/?seite=bio

- ^ Chiasson, Lloyd Jr (1997). The Press on Trial: Crimes and Trials as Media Events. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313300224.

- ^ Knox, Sara L. (1998). Murder: A Tale of Modern American Life. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822320533.

- ^ Cramer, Clayton E. (1994). "Ethical Problems of Mass Murder Coverage in the Mass Media". Journal of Mass Media Ethics. 9.

- ^ Beschle, Donald L. (1997). "What's Guilt (or Deterrence) Got to Do with It?". William and Mary Law Review. 38.

- ^ Eaton, William J. (1995). "Just like O.J.'s Trial, but without Kato". American Journalism Review. 17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Scott, Gina Graham (2005). Homicide by the Rich and Famous: A Century of Prominent Killers. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275983463.

- ^ Lizzie Borden

- ^ "Lizzie Borden Took An Ax". Crime Library. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ Cole, Michael S. M.D. (1994). Cowan Connections. Privately published. pp. 374–380. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ Pylant, James (2004). "The Bewitching Family Tree of Elizabeth Montgomery". Genealogy Magazine.

"Rhonda R. McClure. Finding Your Famous (& Infamous) Ancestors. (Cincinnati: Betterway Books: 2003), pp. 14-16.

- ^ http://lizzieandrewborden.com/Galleries/FallRiverLegend.htm

- ^ Foxton, David (1987). Sepia and Song: A Collection of Historical Documentaries. Nelson Thornes. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-0174324096.

See also

Further reading

A number of works expounding the facts and different theories have been written about the crime. These include:

- Asher, Robert, Lawrence B. Goodheart and Alan Rogers. Murder on Trial: 1620—2002 New York: State University of New York Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0791463772.

- Brown, Arnold R. Lizzie Borden: The Legend, the Truth, the Final Chapter. Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1991, ISBN 1-55853-099-1.

- de Mille, Agnes. Lizzie Borden: A Dance of Death. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1968.

- Kent, David Forty Whacks: New Evidence in the Life and Legend of Lizzie Borden. Yankee Books, 1992, ISBN 0-89909-351-5.

- Kent, David The Lizzie Borden Sourcebook. Boston: Branden Publishing Company, 1992, ISBN 0-8283-1950-2.

- King, Florence. WASP, Where is Thy Sting? Chapter 15, "One WASP's Family, or the Ties That Bind." Stein & Day, 1977, ISBN 0-552-99377-8 (1990 Reprint Edition).

- Lincoln, Victoria. A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967, ISBN 0-930330-35-8.

- Masterton, William L. Lizzie Didn’t Do It! Boston: Branden Publishing Company, 2000, ISBN 0-8283-2052-7.

- Pearson, Edmund Lester. Studies in Murder Ohio State University Press, 1924.

- Pearson, Edmund Lester. Trial of Lizzie Borden, edited, with a history of the case, Doubleday-Doran, 1937. Main text is a transcript of the trial.

- Radin, Edward D. Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story Simon and Schuster, 1961.

- Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past & Present Al-Zach Press, 1999.

- David Rehak. Did Lizzie Borden Axe For It? Angel Dust Publishing, 2008.

- Spiering, Frank. Lizzie: The Story of Lizzie Borden. Dorset Press, 1991, ISBN 0-88029-685-2.

- Sullivan, Robert. Goodbye Lizzie Borden. Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Greene Press, 1974, ISBN 0-14-011416-5.

- Hunter, Evan (see Artistic depictions/Prose Fiction, below) has a video out called Reopened: Lizzie Borden with Ed McBain.

External links

- Lizzie Borden at Find a Grave

- Andrew Borden at Find a Grave

- Famous Trials page about Lizzie Borden

- The Lizzie Borden/Fall River Case Study at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

- The Borden Collection[dead link]. Fall River Historical Society.

- Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast in Fall River, Massachusetts

- The Lizzie Borden Society Forum

- The Hatchet: The Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies