Decay chain: Difference between revisions

→Beta decay chains in uranium & plutonium fission products: - rearranged section |

Undid own revision 394595510 - didn't work out |

||

| Line 671: | Line 671: | ||

== Beta decay chains in uranium & plutonium fission products == |

== Beta decay chains in uranium & plutonium fission products == |

||

| ⚫ | Since the heavy original nuclei always have a greater proportion of neutrons, the [[fission product]] nuclei almost always start out with a neutron/proton ratio significantly greater than what is stable for their mass range. Therefore they undergo multiple [[beta decay]]s in succession, each converting a neutron to a proton. The first decays tend to have higher decay energy and shorter half-life. These last decays may have low decay energy and/or long half-life. |

||

| ⚫ | For example, [[uranium-235]] has 92 protons and 143 neutrons. Fission takes one more neutron, then produces two or three more neutrons; assume that 92 protons and 142 neutrons are available for the two fission product nuclei. Suppose they have mass 99 with 39 protons and 60 neutrons ([[yttrium]]-99), and mass 135 with 53 protons and 82 neutrons ([[iodine]]-135). |

||

{| class="wikitable" align=" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

!Nuclide!!Half life |

!Nuclide!!Half life |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 688: | Line 685: | ||

|[[Isotopes_of_zirconium|<sup>90</sup>Zr]]||stable |

|[[Isotopes_of_zirconium|<sup>90</sup>Zr]]||stable |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{| class="wikitable" align=" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

!Nuclide!!Half life |

!Nuclide!!Half life |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 705: | Line 702: | ||

|[[Isotopes_of_molybdenum|<sup>97</sup>Mo]]||stable |

|[[Isotopes_of_molybdenum|<sup>97</sup>Mo]]||stable |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{| class="wikitable" align=" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

!Nuclide!!Half life |

!Nuclide!!Half life |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 724: | Line 721: | ||

|[[Isotopes_of_ruthenium|<sup>99</sup>Ru]]||Stable |

|[[Isotopes_of_ruthenium|<sup>99</sup>Ru]]||Stable |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{| class="wikitable" align=" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

!Nuclide!!Half life |

!Nuclide!!Half life |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 737: | Line 734: | ||

|[[Isotopes_of_barium|<sup>135</sup>Ba]]||Stable |

|[[Isotopes_of_barium|<sup>135</sup>Ba]]||Stable |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{| class="wikitable" align=" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

!Nuclide!!Half life |

!Nuclide!!Half life |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 754: | Line 751: | ||

|[[Isotopes_of_barium|<sup>137</sup>Ba]]||stable |

|[[Isotopes_of_barium|<sup>137</sup>Ba]]||stable |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{| class="wikitable" align=" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

!Nuclide!!Half life |

!Nuclide!!Half life |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 771: | Line 768: | ||

|[[Isotopes_of_samarium|<sup>144</sup>Sm]]||stable |

|[[Isotopes_of_samarium|<sup>144</sup>Sm]]||stable |

||

|} |

|} |

||

| ⚫ | Since the heavy original nuclei always have a greater proportion of neutrons, the [[fission product]] nuclei almost always start out with a neutron/proton ratio significantly greater than what is stable for their mass range. Therefore they undergo multiple [[beta decay]]s in succession, each converting a neutron to a proton. The first decays tend to have higher decay energy and shorter half-life. These last decays may have low decay energy and/or long half-life. |

||

| ⚫ | For example, [[uranium-235]] has 92 protons and 143 neutrons. Fission takes one more neutron, then produces two or three more neutrons; assume that 92 protons and 142 neutrons are available for the two fission product nuclei. Suppose they have mass 99 with 39 protons and 60 neutrons ([[yttrium]]-99), and mass 135 with 53 protons and 82 neutrons ([[iodine]]-135). |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 15:09, 3 November 2010

In nuclear science, the decay chain refers to the radioactive decay of different discrete radioactive decay products as a chained series of transformations. Most radioactive elements do not decay directly to a stable state, but rather undergo a series of decays until eventually a stable isotope is reached.

Decay stages are referred to by their relationship to previous or subsequent stages. A parent isotope is one that undergoes decay to form a daughter isotope. The daughter isotope may be stable or it may decay to form a daughter isotope of its own. The daughter of a daughter isotope is sometimes called a granddaughter isotope.

The time it takes for a single parent atom to decay to an atom of its daughter isotope can vary widely, not only for different parent-daughter chains, but also for identical pairings of parent and daughter isotopes. While the decay of a single atom occurs spontaneously, the decay of an initial population of identical atoms over time, t, follows a decaying exponential distribution, e−λt, where λ is called a decay constant. Because of this exponential nature, one of the properties of an isotope is its half-life, the time by which half of an initial number of identical parent radioisotopes have decayed to their daughters. Half-lives have been determined in laboratories for thousands of radioisotopes (or, radionuclides). These can range from nearly instantaneous to as much as 1019 years or more.

The intermediate stages often emit more radioactivity than the original radioisotope. When equilibrium is achieved, a granddaughter isotope is present in proportion to its half-life; but since its activity is inversely proportional to its half-life, any nucleid in the decay chain finally contributes as much as the head of the chain. For example, natural uranium is not significantly radioactive, but pitchblende, a uranium ore, is 13 times more radioactive because of the radium and other daughter isotopes it contains. Not only are unstable radium isotopes significant radioactivity emitters, but as the next stage in the decay chain they also generate radon, a heavy, inert, naturally occurring radioactive gas. Rock containing thorium and/or uranium (such as some granites) emits radon gas that can accumulate in enclosed places such as basements or underground mines. Radon exposure is considered the leading cause of lung cancer in non-smokers.[1]

Types

The four most common modes of radioactive decay are: alpha decay, beta decay, inverse beta decay (considered as both positron emission and electron capture), and isomeric transition. Of these decay processes,only alpha decay changes the atomic mass number (A) of the nucleus, and always decreases it by four. Because of this, almost any decay will result in a nucleus whose atomic mass number has the same residue mod 4, dividing all nuclides into four classes. The members of any possible decay chain must be drawn entirely from one of these classes. All four chains also produce helium-4 (alpha particles are helium-4 nuclei).

Three main decay chains (or families) are observed in nature, commonly called the thorium series, the radium series, and the actinium series, representing three of these four classes, and ending in three different, stable isotopes of lead. The mass number of every isotope in these chains can be represented as A = 4n, A = 4n + 2, and A = 4n + 3, respectively. The long-lived starting isotopes of these three isotopes, respectively thorium-232, uranium-238, and uranium-235, have existed since the formation of the earth. The plutonium isotopes plutonium-244 and plutonium-239 have also been found in trace amounts on earth.[2]

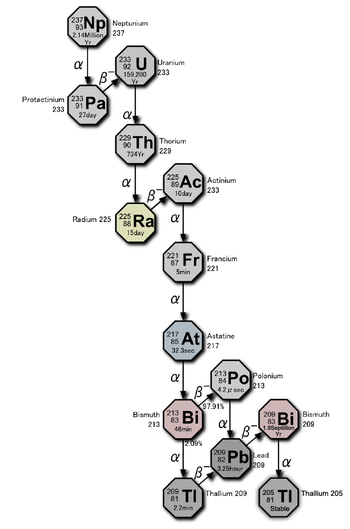

Due to the quite short half-life of its starting isotope neptunium-237 (2.14 million years), the fourth chain, the neptunium series with A = 4n + 1, is already extinct in nature, except for the final rate-limiting step, decay of bismuth-209. The ending isotope of this chain is now known to be thallium-205. Some older sources give the final isotope as bismuth-209, but it was recently discovered that it is radioactive, with a half-life of 1.9×1019 years.

There are also many shorter chains, for example that of carbon-14. On Earth, most of the starting isotopes of these chains are generated by cosmic radiation.

Actinide alpha decay chains

| Actinides[3] by decay chain | Half-life range (a) |

Fission products of 235U by yield[4] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4n | 4n + 1 | 4n + 2 | 4n + 3 | 4.5–7% | 0.04–1.25% | <0.001% | ||

| 228Ra№ | 4–6 a | 155Euþ | ||||||

| 248Bk[5] | > 9 a | |||||||

| 244Cmƒ | 241Puƒ | 250Cf | 227Ac№ | 10–29 a | 90Sr | 85Kr | 113mCdþ | |

| 232Uƒ | 238Puƒ | 243Cmƒ | 29–97 a | 137Cs | 151Smþ | 121mSn | ||

| 249Cfƒ | 242mAmƒ | 141–351 a |

No fission products have a half-life | |||||

| 241Amƒ | 251Cfƒ[6] | 430–900 a | ||||||

| 226Ra№ | 247Bk | 1.3–1.6 ka | ||||||

| 240Pu | 229Th | 246Cmƒ | 243Amƒ | 4.7–7.4 ka | ||||

| 245Cmƒ | 250Cm | 8.3–8.5 ka | ||||||

| 239Puƒ | 24.1 ka | |||||||

| 230Th№ | 231Pa№ | 32–76 ka | ||||||

| 236Npƒ | 233Uƒ | 234U№ | 150–250 ka | 99Tc₡ | 126Sn | |||

| 248Cm | 242Pu | 327–375 ka | 79Se₡ | |||||

| 1.33 Ma | 135Cs₡ | |||||||

| 237Npƒ | 1.61–6.5 Ma | 93Zr | 107Pd | |||||

| 236U | 247Cmƒ | 15–24 Ma | 129I₡ | |||||

| 244Pu | 80 Ma |

... nor beyond 15.7 Ma[7] | ||||||

| 232Th№ | 238U№ | 235Uƒ№ | 0.7–14.1 Ga | |||||

| ||||||||

In the four tables below, the minor branches of decay (with the branching ratio of less than 0.0001%) are omitted. The energy release includes the total kinetic energy of all the emitted particles (electrons, alpha particles, gamma quanta, neutrinos, Auger electrons and X-rays) and the recoil nucleus, assuming that the original nucleus was at rest. The letter 'a' represents a year.

In the tables below (except neptunium), the historic names of the naturally occurring nuclides are also given. These names were used at the time when the decay chains were first discovered and investigated. From these names one can infer the particular chain to which the nuclide belongs. Also, the names indicate similarities: for example, Tn, Rn and An are all inert gases.

Thorium series

The 4n chain of Th-232 is commonly called the "thorium series." Beginning with naturally occurring thorium-232, this series includes the following elements: Actinium, bismuth, lead, polonium, radium, and radon. All are present, at least transiently, in any natural thorium-containing sample, whether metal, compound, or mineral.

| nuclide | historic name (short) | historic name (long) | decay mode | half life | energy released, MeV | product of decay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 252Cf | α | 2.645 a | 6.1181 | 248Cm | ||

| 248Cm | α | 3.4×105 a | 6.260 | 244Pu | ||

| 244Pu | α | 8×107 a | 4.589 | 240U | ||

| 240U | β− | 14.1 h | .39 | 240Np | ||

| 240Np | β− | 1.032 h | 2.2 | 240Pu | ||

| 240Pu | α | 6561 a | 5.1683 | 236U | ||

| 236U | α | 2.3·107 a | 4.494 | 232Th | ||

| 232Th | Th | Thorium | α | 1.405·1010 a | 4.081 | 228Ra |

| 228Ra | MsTh1 | Mesothorium 1 | β− | 5.75 a | 0.046 | 228Ac |

| 228Ac | MsTh2 | Mesothorium 2 | β− | 6.25 h | 2.124 | 228Th |

| 228Th | RdTh | Radiothorium | α | 1.9116 a | 5.520 | 224Ra |

| 224Ra | ThX | Thorium X | α | 3.6319 d | 5.789 | 220Rn |

| 220Rn | Tn | Thoron | α | 55.6 s | 6.404 | 216Po |

| 216Po | ThA | Thorium A | α | 0.145 s | 6.906 | 212Pb |

| 212Pb | ThB | Thorium B | β− | 10.64 h | 0.570 | 212Bi |

| 212Bi | ThC | Thorium C | β− 64.06% α 35.94% |

60.55 min | 2.252 6.208 |

212Po 208Tl |

| 212Po | ThC' | Thorium C' | α | 299 ns | 8.955 | 208Pb |

| 208Tl | ThC" | Thorium C" | β− | 3.053 min | 4.999 | 208Pb |

| 208Pb | . | stable | . | . |

Neptunium series

The 4n + 1 chain of Np-237 is commonly called the "neptunium series." In this series, only two of the elements are found naturally, bismuth and thallium. A smoke detector containing an americium-241 ionization chamber accumulates a significant amount of neptunium-237 as its americium decays; the following elements are also present in it, at least transiently, as decay products of the neptunium: Actinium, astatine, bismuth, francium, lead, polonium, protactinium, radium, thallium, thorium, and uranium. Since this series was only studied more recently, its nuclides do not have historic names.

| nuclide | decay mode | half life | energy released, MeV | product of decay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 249Cf | α | 351 a | 5.813+.388 | 245Cm |

| 245Cm | α | 8500 a | 5.362+.175 | 241Pu |

| 241Pu | β− | 14.4 a | 0.021 | 241Am |

| 241Am | α | 432.7 a | 5.638 | 237Np |

| 237Np | α | 2.14·106 a | 4.959 | 233Pa |

| 233Pa | β− | 27.0 d | 0.571 | 233U |

| 233U | α | 1.592·105 a | 4.909 | 229Th |

| 229Th | α | 7340 a | 5.168 | 225Ra |

| 225Ra | β− | 14.9 d | 0.36 | 225Ac |

| 225Ac | α | 10.0 d | 5.935 | 221Fr |

| 221Fr | α | 4.8 min | 6.3 | 217At |

| 217At | α | 32 ms | 7.0 | 213Bi |

| 213Bi | β− 97.80% α 2.20% |

46.5 min | 1.423 5.87 |

213Po 209Tl |

| 213Po | α | 3.72 μs | 8.536 | 209Pb |

| 209Tl | β− | 2.2 min | 3.99 | 209Pb |

| 209Pb | β− | 3.25 h | 0.644 | 209Bi |

| 209Bi | α | 1.9·1019 a | 3.14 | 205Tl |

| 205Tl | . | stable | . | . |

Radium series (also known as Uranium series)

The 4n+2 chain of U-238 is commonly called the "radium series" (sometimes "uranium series"). Beginning with naturally occurring uranium-238, this series includes the following elements: astatine, bismuth, lead, polonium, protactinium, radium, radon, thallium, and thorium. All are present, at least transiently, in any natural uranium-containing sample, whether metal, compound, or mineral.

| nuclide | historic name (short) | historic name (long) | decay mode | half life | MeV | product of decay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 238U | U | Uranium | α | 4.468·109 a | 4.270 | 234Th |

| 234Th | UX1 | Uranium X1 | β− | 24.10 d | 0.273 | 234mPa |

| 234mPa | UX2 | Uranium X2 | β− 99.84 % IT 0.16 % |

1.16 min | 2.271 0.074 |

234U 234Pa |

| 234Pa | UZ | Uranium Z | β− | 6.70 h | 2.197 | 234U |

| 234U | UII | Uranium two | α | 245500 a | 4.859 | 230Th |

| 230Th | Io | Ionium | α | 75380 a | 4.770 | 226Ra |

| 226Ra | Ra | Radium | α | 1602 a | 4.871 | 222Rn |

| 222Rn | Rn | Radon | α | 3.8235 d | 5.590 | 218Po |

| 218Po | RaA | Radium A | α 99.98 % β− 0.02 % |

3.10 min | 6.115 0.265 |

214Pb 218At |

| 218At | α 99.90 % β− 0.10 % |

1.5 s | 6.874 2.883 |

214Bi 218Rn | ||

| 218Rn | α | 35 ms | 7.263 | 214Po | ||

| 214Pb | RaB | Radium B | β− | 26.8 min | 1.024 | 214Bi |

| 214Bi | RaC | Radium C | β− 99.98 % α 0.02 % |

19.9 min | 3.272 5.617 |

214Po 210Tl |

| 214Po | RaC' | Radium C' | α | 0.1643 ms | 7.883 | 210Pb |

| 210Tl | RaC" | Radium C" | β− | 1.30 min | 5.484 | 210Pb |

| 210Pb | RaD | Radium D | β− | 22.3 a | 0.064 | 210Bi |

| 210Bi | RaE | Radium E | β− 99.99987% α 0.00013% |

5.013 d | 1.426 5.982 |

210Po 206Tl |

| 210Po | RaF | Radium F | α | 138.376 d | 5.407 | 206Pb |

| 206Tl | RaE" | Radium E" | β− | 4.199 min | 1.533 | 206Pb |

| 206Pb | - | stable | - | - |

Actinium series

The 4n+3 chain of Uranium-235 is commonly called the "actinium series". Beginning with the naturally-occurring isotope U-235, this decay series includes the following elements: Actinium, astatine, bismuth, francium, lead, polonium, protactinium, radium, radon, thallium, and thorium. All are present, at least transiently, in any sample containing uranium-235, whether metal, compound, ore, or mineral. This series terminates with the stable isotope lead-207.

| nuclide | historic name (short) | historic name (long) | decay mode | half life | energy released, MeV | product of decay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 239Pu | α | 2.41·104 a | 5.244 | 235U | ||

| 235U | AcU | Actin Uranium | α | 7.04·108 a | 4.678 | 231Th |

| 231Th | UY | Uranium Y | β− | 25.52 h | 0.391 | 231Pa |

| 231Pa | α | 32760 a | 5.150 | 227Ac | ||

| 227Ac | Ac | Actinium | β− 98.62% α 1.38% |

21.772 a | 0.045 5.042 |

227Th 223Fr |

| 227Th | RdAc | Radioactinium | α | 18.68 d | 6.147 | 223Ra |

| 223Fr | AcK | Actinium K | β− 99.994% α 0.006% |

22.00 min | 1.149 5.340 |

223Ra 219At |

| 223Ra | AcX | Actinium X | α | 11.43 d | 5.979 | 219Rn |

| 219At | α 97.00% β− 3.00% |

56 s | 6.275 1.700 |

215Bi 219Rn | ||

| 219Rn | An | Actinon | α | 3.96 s | 6.946 | 215Po |

| 215Bi | β− | 7.6 min | 2.250 | 215At | ||

| 215Po | AcA | Actinium A | α 99.99977% β− 0.00023% |

1.781 ms | 7.527 0.715 |

211Pb 215At |

| 215At | α | 0.1 ms | 8.178 | 211Bi | ||

| 211Pb | AcB | Actinium B | β− | 36.1 min | 1.367 | 211Bi |

| 211Bi | AcC | Actinium C | α 99.724% β− 0.276% |

2.14 min | 6.751 0.575 |

207Tl 211Po |

| 211Po | AcC' | Actinium C' | α | 516 ms | 7.595 | 207Pb |

| 207Tl | AcC" | Actinium C" | β− | 4.77 min | 1.418 | 207Pb |

| 207Pb | . | stable | . | . |

Beta decay chains in uranium & plutonium fission products

| Nuclide | Half life |

|---|---|

| 90Kr | 32.32(9) s |

| 90Rb | 158(5) s |

| 90Sr | 28.90(3) a |

| 90Y | 64.053(20) h |

| 90Zr | stable |

| Nuclide | Half life |

|---|---|

| 97Kr | 63(4) ms |

| 97Rb | 169.9(7) ms |

| 97Sr | 429(5) ms |

| 97Y | 3.75(3) s |

| 97Zr | 16.744(11) h |

| 97Nb | 72.1(7) min |

| 97Mo | stable |

| Nuclide | Half life |

|---|---|

| 99Sr | 0.269(1) s |

| 99Y | 1.470(7) s |

| 99Zr | 2.1(1) s |

| 99Nb | 15.0(2) s |

| 99Mo | 2.7489(6) d |

| 99mTc | 6.0058(12) h |

| 99Tc | 2.111(12)E+5 a |

| 99Ru | Stable |

| Nuclide | Half life |

|---|---|

| 135Te | 19.0(2) s |

| 135I | 6.57(2) h |

| 135Xe | 9.14(2) h |

| 135Cs | 2.3(3)E+6 a |

| 135Ba | Stable |

| Nuclide | Half life |

|---|---|

| 137Te | 2.49(5) s |

| 137I | Stable |

| 137Xe | 3.818(13) min |

| 137Cs | 30.1671(13) a |

| 137m2Ba | 0.59(10) µs |

| 137m1Ba | 2.552(1) min |

| 137Ba | stable |

| Nuclide | Half life |

|---|---|

| 144Ba | 11.5(2) s |

| 144La | 40.8(4) s |

| 144Ce | 284.91(5) d |

| 144Pr | 17.28(5) min |

| 144Nd | 2.29(16)E+15 a |

| 144Pm | 363(14) d |

| 144Sm | stable |

Since the heavy original nuclei always have a greater proportion of neutrons, the fission product nuclei almost always start out with a neutron/proton ratio significantly greater than what is stable for their mass range. Therefore they undergo multiple beta decays in succession, each converting a neutron to a proton. The first decays tend to have higher decay energy and shorter half-life. These last decays may have low decay energy and/or long half-life.

For example, uranium-235 has 92 protons and 143 neutrons. Fission takes one more neutron, then produces two or three more neutrons; assume that 92 protons and 142 neutrons are available for the two fission product nuclei. Suppose they have mass 99 with 39 protons and 60 neutrons (yttrium-99), and mass 135 with 53 protons and 82 neutrons (iodine-135).

See also

Notes

- ^ http://www.epa.gov/radon/

- ^

D.C. Hoffman, F.O. Lawrence, J.L. Mewherter, F.M. Rourke (1971). "Detection of Plutonium-244 in Nature". Nature. 234: 132–134. doi:10.1038/234132a0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Plus radium (element 88). While actually a sub-actinide, it immediately precedes actinium (89) and follows a three-element gap of instability after polonium (84) where no nuclides have half-lives of at least four years (the longest-lived nuclide in the gap is radon-222 with a half life of less than four days). Radium's longest lived isotope, at 1,600 years, thus merits the element's inclusion here.

- ^ Specifically from thermal neutron fission of uranium-235, e.g. in a typical nuclear reactor.

- ^ Milsted, J.; Friedman, A. M.; Stevens, C. M. (1965). "The alpha half-life of berkelium-247; a new long-lived isomer of berkelium-248". Nuclear Physics. 71 (2): 299. Bibcode:1965NucPh..71..299M. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(65)90719-4.

"The isotopic analyses disclosed a species of mass 248 in constant abundance in three samples analysed over a period of about 10 months. This was ascribed to an isomer of Bk248 with a half-life greater than 9 [years]. No growth of Cf248 was detected, and a lower limit for the β− half-life can be set at about 104 [years]. No alpha activity attributable to the new isomer has been detected; the alpha half-life is probably greater than 300 [years]." - ^ This is the heaviest nuclide with a half-life of at least four years before the "sea of instability".

- ^ Excluding those "classically stable" nuclides with half-lives significantly in excess of 232Th; e.g., while 113mCd has a half-life of only fourteen years, that of 113Cd is eight quadrillion years.

References

- C.M. Lederer, J.M. Hollander, I. Perlman (1968). Table of Isotopes (6th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Decay chains

- Uranium-238 decay chain

- Government website listing isotopes and decay energies

- National Nuclear Data Center Freely available databases that can be used to check or construct decay chains. Fully referenced.

The Live Chart of Nuclides - IAEA with decay chains, in Java or HTML

The Live Chart of Nuclides - IAEA with decay chains, in Java or HTML