Iatrogenesis: Difference between revisions

rvt some medical malpractice law firm website is NOT a reliable source for that info |

m grammatical correction. |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The terms '''iatrogenesis''' and '''iatrogenic artifact''' refer to inadvertent [[adverse effect (medicine)|adverse effect]]s or [[complication (medicine)|complication]]s caused by or resulting from [[medicine|medical]] treatment or advice. In addition to harmful consequences of actions by physicians, iatrogenesis can also refer to actions by other healthcare professionals, such as [[psychologist]]s, [[therapist]]s, [[pharmacist]]s, [[nurse]]s, [[dentist]]s, and others. Iatrogenesis is not restricted to conventional medicine: it can also result from [[complementary and alternative medicine]] treatments. |

The terms '''iatrogenesis''' and '''iatrogenic artifact''' refer to inadvertent [[adverse effect (medicine)|adverse effect]]s or [[complication (medicine)|complication]]s caused by or resulting from [[medicine|medical]] treatment or advice. In addition to harmful consequences of actions by physicians, iatrogenesis can also refer to actions by other healthcare professionals, such as [[psychologist]]s, [[therapist]]s, [[pharmacist]]s, [[nurse]]s, [[dentist]]s, and others. Iatrogenesis is not restricted to conventional medicine: it can also result from [[complementary and alternative medicine]] treatments. |

||

Some iatrogenic artifacts are clearly defined and easily recognized, such as a complication following a surgical procedure. Some less obvious ones can require significant investigation to identify, such as complex [[drug interaction]]s. Furthermore, some conditions have been described for which it is unknown, unproven or even controversial whether they |

Some iatrogenic artifacts are clearly defined and easily recognized, such as a complication following a surgical procedure. Some less obvious ones can require significant investigation to identify, such as complex [[drug interaction]]s. Furthermore, some conditions have been described for which it is unknown, unproven or even controversial whether they are iatrogenic or not; this has been encountered particularly with regard to various psychological and chronic-pain conditions. Research in these areas continues. |

||

Causes of iatrogenesis include chance, [[medical error]], [[negligence]], [[social control]] {{Clarify|date=October 2010}}and the [[adverse effect]]s or [[drug interaction|interactions]] of prescription drugs. In the United States, an estimated 44,000 to 98,000 deaths per year may be attributed in some part to iatrogenesis.<ref name="pmid10940133">{{Cite journal|author=Weingart SN, Ship AN, Aronson MD |title=Confidential clinician-reported surveillance of adverse events among medical inpatients |journal=[[J Gen Intern Med]] |volume=15 |issue=7 |pages=470–7 |year=2000 |pmid=10940133 |doi=10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06269.x |pmc=1495482}}</ref> |

Causes of iatrogenesis include chance, [[medical error]], [[negligence]], [[social control]] {{Clarify|date=October 2010}}and the [[adverse effect]]s or [[drug interaction|interactions]] of prescription drugs. In the United States, an estimated 44,000 to 98,000 deaths per year may be attributed in some part to iatrogenesis.<ref name="pmid10940133">{{Cite journal|author=Weingart SN, Ship AN, Aronson MD |title=Confidential clinician-reported surveillance of adverse events among medical inpatients |journal=[[J Gen Intern Med]] |volume=15 |issue=7 |pages=470–7 |year=2000 |pmid=10940133 |doi=10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06269.x |pmc=1495482}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:19, 25 November 2010

The terms iatrogenesis and iatrogenic artifact refer to inadvertent adverse effects or complications caused by or resulting from medical treatment or advice. In addition to harmful consequences of actions by physicians, iatrogenesis can also refer to actions by other healthcare professionals, such as psychologists, therapists, pharmacists, nurses, dentists, and others. Iatrogenesis is not restricted to conventional medicine: it can also result from complementary and alternative medicine treatments.

Some iatrogenic artifacts are clearly defined and easily recognized, such as a complication following a surgical procedure. Some less obvious ones can require significant investigation to identify, such as complex drug interactions. Furthermore, some conditions have been described for which it is unknown, unproven or even controversial whether they are iatrogenic or not; this has been encountered particularly with regard to various psychological and chronic-pain conditions. Research in these areas continues.

Causes of iatrogenesis include chance, medical error, negligence, social control [clarification needed]and the adverse effects or interactions of prescription drugs. In the United States, an estimated 44,000 to 98,000 deaths per year may be attributed in some part to iatrogenesis.[1]

History

Etymologically, the term "iatrogenesis" means "brought forth by a healer" (iatros means healer in Greek); as such, in its earlier forms, it could refer to good or bad effects.

Since at least the time of Hippocrates, people have recognized the potential damaging effects of a healer's actions. The old mandate "first do no harm" (primum non nocere) is an important clause of medical ethics, and iatrogenic illness or death caused purposefully, or by avoidable error or negligence on the healer's part became a punishable offense in many civilizations.[citation needed]

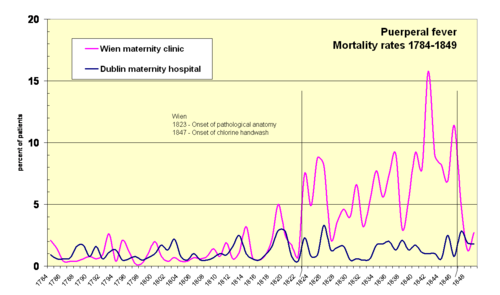

The transfer of pathogens from the autopsy room to maternity patients, leading to shocking historical mortality rates of puerperal fever (a.k.a. "childbed fever") at maternity institutions in the 19th century, was a major iatrogenic catastrophe of that time.[citation needed] The infection mechanism was first identified by Ignaz Semmelweis.

With the development of scientific medicine in the 20th century, it could be expected that iatrogenic illness or death would be more easily avoided. Antiseptics, anesthesia, antibiotics, and better surgical techniques have been developed to decrease iatrogenic mortality.

Sources of iatrogenesis

Examples of iatrogenesis:

- Risk associated with medical interventions

- adverse effects of prescription drugs

- over-use of drugs, (causing - for example - antibiotic resistance in bacteria)

- prescription drug interaction

- medical error

- wrong prescription, perhaps due to illegible handwriting, typos on computer.

- negligence

- faulty procedures, techniques, information, methods, or equipment.

Causes and consequences

Medical error and negligence

Iatrogenic conditions do not necessarily result from medical errors, such as mistakes made in surgery, or the prescription or dispensing of the wrong therapy, such as a drug. In fact, intrinsic and sometimes adverse effects of a medical treatment are iatrogenic. For example, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, due to the needed aggressiveness of the therapeutic agents, frequently produce iatrogenic effects such as hair loss, anemia, vomiting, nausea, brain damage, lymphedema, infertility, etc. The loss of functions resulting from the required removal of a diseased organ also counts as iatrogenesis, thus we find (for example) iatrogenic diabetes brought on by removal of all or part of the pancreas.

Other situations may involve actual negligence or faulty procedures, such as when pharmacotherapists produce handwritten prescriptions for drugs.

Adverse effects

A very common iatrogenic effect is caused by drug interaction, i.e., when pharmacotherapists fail to check for all medications a patient is taking and prescribe new ones which interact agonistically or antagonistically (potentiate or decrease the intended therapeutic effect). Such situations an cause significant morbidity and mortality. Adverse reactions, such as allergic reactions to drugs, even when unexpected by pharmacotherapists, are also classified as iatrogenic.

The evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria is iatrogenic as well.[2] Bacteria strains resistant to antibiotics have evolved in response to the overprescription of antibiotic drugs.[citation needed]

Certain drugs are toxic in their own right in therapeutic doses because of their mechanism of action. Alkylating antineoplastic agents, for example, cause DNA damage, which is more harmful to cancer cells than regular cells. However, alkylation causes severe side-effects and is actually carcinogenic in its own right, potentially leading to the development of secondary tumors. Similarly, arsenic-based medications like melarsoprol for trypanosomiasis cause arsenic poisoning.

Psychology

In psychology, iatrogenesis can occur due to misdiagnosis (including diagnosis with a false condition as was the case of hystero-epilepsy[3]). Conditions hypothesized as partially or completely iatrogenic include bipolar disorder,[4] dissociative identity disorder,[3][5] fibromyalgia,[6] somatoform disorder,[7] chronic fatigue syndrome,[7] posttraumatic stress disorder,[8] substance abuse,[9] antisocial youths[10] and others,[11] though research is equivocal for each condition.[citation needed] The degree of association of any particular condition with iatrogenesis is unclear and in some cases controversial. The over-diagnosis of psychological conditions (with the assignment of mental illness terminology) may relate primarily to clinician dependence on subjective criteria.[citation needed] The assignment of pathological nomenclature is rarely a benign process and can easily rise to the level of emotional iatrogenesis, especially when no alternatives outside of the diagnostic naming process have been considered.[citation needed]

Iatrogenic poverty

Meessen et al. used the term “iatrogenic poverty” to describe impoverishment induced by medical care.[12] Impoverishment is described for households exposed to catastrophic health expenditure[13] or to hardship financing.[14] Every year, worldwide, over 100,000 households fall into poverty due to health care expenses. Especially in countries in economic transition, the willingness to pay for health care is increasing and the supply side does not stay behind and develops very fast. But, the regulatory and protective capacity in those countries is often lagging behind. Patients easily fall in a vicious cycle of illness, ineffective therapies, consumption of savings, indebtedness, sale of productive assets and eventually poverty.

Incidence and importance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2010) |

Iatrogenesis is a major phenomenon, and a severe risk to patients. A study carried out in 1981 more than one-third of illnesses of patients in a university hospital were iatrogenic, nearly one in ten were considered major, and in 2% of the patients, the iatrogenic disorder ended in death. Complications were most strongly associated with exposure to drugs and medications.[15] In another study, the main factors leading to problems were inadequate patient evaluation, lack of monitoring and follow-up, and failure to perform necessary tests.[citation needed]

In the United States, figures suggest estimated deaths per year of:

- 12,000 due to unnecessary surgery

- 7,000 due to medication errors in hospitals

- 20,000 due to other errors in hospitals

- 80,000 due to infections in hospitals

- 106,000 due to non-error, negative effects of drugs[citation needed]

Based on these figures, iatrogenesis may cause 225,000 deaths per year in the United States (excluding recognizable error).[citation needed] These estimates are lower than those in an earlier IOM report, which might suggest from 230,000 to 284,000 iatrogenic deaths.[citation needed] These figures are likely exaggerated, however, as they are based on recorded deaths in hospitals rather than in the general population. Even so, the large gap separating these estimates deaths from cerebrovascular disease would still suggest that iatrogenic illness constitutes the third leading cause of death in the United States, after deaths from heart disease and cancer.[citation needed]

See also

- Ivan Illich — Medical Nemesis (book)

- Adverse drug reaction

- Adverse effect (medicine)

- Bedsore

- Bioethics

- Cascade effect

- Classification of Pharmaco-Therapeutic Referrals

- Complication (medicine)

- Fatal Care: Survive in the U.S. Health System (book)

- Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine

- Medical error

- Nocebo

- Patient safety

- Placebo

- Polypharmacy

- Medical harm

- Nosocomial infection

References

- ^ Weingart SN, Ship AN, Aronson MD (2000). "Confidential clinician-reported surveillance of adverse events among medical inpatients". J Gen Intern Med. 15 (7): 470–7. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06269.x. PMC 1495482. PMID 10940133.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Finland M (1979). "Emergence of antibiotic resistance in hospitals, 1935-1975". Rev. Infect. Dis. 1 (1): 4–22. PMID 45521.

- ^ a b Spanos, Nicholas P. (1996). Multiple Identities & False Memories: A Sociocognitive Perspective. American Psychological Association (APA). ISBN 1-55798-340-2.

- ^

Pruett Jr, John R. (2004). "Recent Advances in Prepubertal Mood Disorders: Phenomenology and Treatment". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 17 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1097/00001504-200401000-00006. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Braun, B.G. (1989). "Iatrophilia and Iatrophobia in the diagnosis and treatment of MPD (Morose Parasitic Dynamism)" (PDF). Dissociation. 2 (2): 66–9. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ Hadler, N.M. (1997). "Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and other iatrogenic diagnostic algorithms. Do some labels escalate illness in vulnerable patients?". Postgrad Med. 102 (6): 43. PMID 9270707.

- ^ a b Abbey, S.E. (1993). "Somatization, illness attribution and the sociocultural psychiatry of chronic fatigue syndrome". Ciba Found Symp. 173: 238–52. PMID 8491101.

- ^ Boscarino, JA (2004). "Evaluation of the Iatrogenic Effects of Studying Persons Recently Exposed to a Mass Urban Disaster" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Moos, R.H. (2005). "Iatrogenic effects of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders: prevalence , predictors, prevention". Addiction. 100 (5): 595–604. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01073.x. PMID 15847616.

- ^ Weiss, B. (2005). "Iatrogenic effects of group treatment for antisocial youths". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 73 (6): 1036–1044. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1036. PMID 16392977.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Kouyanou, K (1 November 1997). "Iatrogenic factors and chronic pain". Psychosomatic Medicine. 59 (6): 597–604. PMID 9407578.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Meessen,B., Zhenzhong,Z., Van Damme,W., Devadasan,N., Criel,B., Bloom,G. (2003). "Iatrogenic poverty". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 8 (7): 581–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01081.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu; Evans, DB; Carrin, G; Aguilar-Rivera, AM; Musgrove, P; Evans, T; et al. (2007). "Protecting Households from Catastrophic Health Spending". Health Affairs. 26 (4): 972–83. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.972. PMID 17630440.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Kruk; Goldmann, E.; Galea, S.; et al. (2009). "Borrowing And Selling To Pay For Health Care In Low- And Middle-Income Countries". Health Affairs. 28 (4): 10056–66. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1056. PMID 19597204.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Steel K, Gertman PM, Crescenzi C, Anderson J (1981). "Iatrogenic illness on a general medical service at a university hospital". N. Engl. J. Med. 304 (11): 638–42. doi:10.1056/NEJM198103123041104. PMID 7453741.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Valenstein, Elliot S. (1986). Great and desperate cures: the rise and decline of psychosurgery and other radical treatments for mental illness. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0465027105.

- Rice, Stephen (1988). Some Doctors Make You Sick: The Scandal of Medical Incompetence. Sydney, Australia: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0207159505.

External links