Abjad: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Added the etymology for the name |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

According to the formulations of Daniels, abjads differ from [[alphabet]]s in that only consonants, not vowels, are represented among the basic [[grapheme]]s. Abjads differ from [[abugida]]s, another category invented by Daniels, in that in abjads the vowel sound is ''implied'' by [[phonology]], and where [[Diacritic|vowel marks]] exist for the system, such as [[niqqud|nikkud]] for [[Hebrew]] and [[harakat|harakāt]] for [[Arabic]], their use is optional and not the dominant (or literate) form. Abugidas always mark the vowels (other than the "inherent" vowel) with a diacritic, a minor attachment to the letter, or a standalone [[glyph]]. Some abugidas use a special symbol to ''suppress'' the [[inherent vowel]] so that the consonant alone can be properly represented. In a [[syllabary]], a grapheme denotes a complete syllable, that is, either a lone vowel sound or a combination of a vowel sound with one or more consonant sounds. |

According to the formulations of Daniels, abjads differ from [[alphabet]]s in that only consonants, not vowels, are represented among the basic [[grapheme]]s. Abjads differ from [[abugida]]s, another category invented by Daniels, in that in abjads the vowel sound is ''implied'' by [[phonology]], and where [[Diacritic|vowel marks]] exist for the system, such as [[niqqud|nikkud]] for [[Hebrew]] and [[harakat|harakāt]] for [[Arabic]], their use is optional and not the dominant (or literate) form. Abugidas always mark the vowels (other than the "inherent" vowel) with a diacritic, a minor attachment to the letter, or a standalone [[glyph]]. Some abugidas use a special symbol to ''suppress'' the [[inherent vowel]] so that the consonant alone can be properly represented. In a [[syllabary]], a grapheme denotes a complete syllable, that is, either a lone vowel sound or a combination of a vowel sound with one or more consonant sounds. |

||

The name "Abjad" derives from the first letter of a the alphabet, excluding those that have a repeated base. For example [[ب]] (ba) and [[ت]] (ta) have the same base. Henceforth, in the abjad, the first letter of the same base is used, and the others omitted ; "أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د " became just "أ ب ج د " or, "أبجد", meaning "Abjad". |

|||

==Origins== |

==Origins== |

||

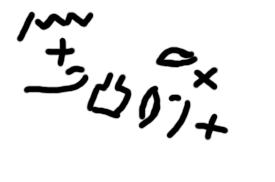

[[Image:Ba`alat.png|thumb|275px|A specimen of Proto-Sinaitic script containing a phrase which may mean 'death to Baalat'. The line running from the upper left to lower right reads ''mt l b<sup>c</sup>lt''.]] |

[[Image:Ba`alat.png|thumb|275px|A specimen of Proto-Sinaitic script containing a phrase which may mean 'death to Baalat'. The line running from the upper left to lower right reads ''mt l b<sup>c</sup>lt''.]] |

||

Revision as of 06:04, 4 June 2011

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Template:Writing systems sidebar An abjad is a type of writing system in which each symbol always or usually[1] stands for a consonant; the reader must supply the appropriate vowel. It is a term suggested by Peter T. Daniels[2] to replace the common terms consonantary or consonantal alphabet or syllabary to refer to the family of scripts called West Semitic. In popular usage, abjads often contain the word "alphabet" in their names, such as "Arabic alphabet" and "Phoenician alphabet". The name abjad itself derives from the Arabic word for alphabet. The word "Alphabet" in English has a source in Phonecian language the first two letters of which were A (Aleph) and B (Beth), hence Alephbeth. In Arabic, A (Alif),B (Ba), J (Jeem), D (Daal) make the word "Abjad" which means "Alphabet". It is also used to enumerate a list like a,b,c,d etc are used in English language.

Terminology

According to the formulations of Daniels, abjads differ from alphabets in that only consonants, not vowels, are represented among the basic graphemes. Abjads differ from abugidas, another category invented by Daniels, in that in abjads the vowel sound is implied by phonology, and where vowel marks exist for the system, such as nikkud for Hebrew and harakāt for Arabic, their use is optional and not the dominant (or literate) form. Abugidas always mark the vowels (other than the "inherent" vowel) with a diacritic, a minor attachment to the letter, or a standalone glyph. Some abugidas use a special symbol to suppress the inherent vowel so that the consonant alone can be properly represented. In a syllabary, a grapheme denotes a complete syllable, that is, either a lone vowel sound or a combination of a vowel sound with one or more consonant sounds.

The name "Abjad" derives from the first letter of a the alphabet, excluding those that have a repeated base. For example ب (ba) and ت (ta) have the same base. Henceforth, in the abjad, the first letter of the same base is used, and the others omitted ; "أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د " became just "أ ب ج د " or, "أبجد", meaning "Abjad".

Origins

All known abjads belong to the Semitic family of scripts. These scripts are thought to derive from the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet (dated to about 1500 BC) which is thought to derive from Egyptian hieroglyphs. The abjad was significantly simpler than the earlier hieroglyphs. The number of distinct glyphs was reduced tremendously, at the cost of increased ambiguity.

The first abjad to gain widespread usage was the Phoenician abjad. Unlike other contemporary scripts, such as Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Phoenician script consisted of only about two dozen symbols. This made the script easy to learn, and Phoenician seafaring merchants took the script wherever they went. Phoenician gave way to a number of new writing systems, including the Greek alphabet, and Aramaic, a widely used abjad. Greek evolved into the modern western alphabets, such as Latin and Cyrillic, while Aramaic became the ancestor of many modern abjads and abugidas of Asia.

Aramaic spread across Asia, reaching as far as India and becoming Brahmi, the ancestral abugida to most modern Indian and Southeast Asian scripts. In the Middle East, Aramaic gave rise to the Hebrew and Nabataean abjads, which retained many of the Aramaic letter forms. The Syriac script was a cursive variation of Aramaic. It is unclear whether the Arabic abjad was derived from Nabatean or Syriac.

Impure abjads

"Impure" abjads have characters for some vowels, optional vowel diacritics, or both. The term "pure" abjad refers to scripts entirely lacking in vowel indicators. However, most modern abjads, such as Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic and Avestan, are "impure" abjads, that is, they also contain symbols for some of the vowel phonemes. An example of a pure abjad is ancient Phoenician.

Addition of vowels

In the 9th century BC, the Greeks adapted the Phoenician script for use in their own language. The phonetic structure of the Greek language created too many ambiguities when the vowels went unrepresented, so the script was modified. They did not need letters for the guttural sounds represented by aleph, he, heth or ayin, so these symbols were assigned vocalic values. The letters waw and yod were also used. The Greek alphabet thus became the world's first "true" alphabet.

Abugidas developed along a slightly different route. The basic consonantal symbol was considered to have an inherent "a" vowel sound. Hooks or short lines attached to various parts of the basic letter modify the vowel. In this way, the South Arabian alphabet evolved into the Ge'ez alphabet between the 5th century BC and the 5th century AD. Similarly, around the 3rd century BC, the Brāhmī script developed (from the Aramaic abjad, it has been hypothesised).

Abjads and the structure of Semitic languages

The abjad form of writing is well-adapted to the morphological structure of the Semitic languages it was developed to write. This is because words in Semitic languages are formed from a root consisting of (usually) three consonants, the vowels being used to indicate inflectional or derived forms. For instance, from the Arabic root ذبح Ḏ-B-Ḥ (to sacrifice) can be derived the forms ذَبَح ḏabaḥa (he sacrificed), ذَبَحْتَ ḏabaḥta (you (masculine singular) sacrificed), ذَبَّحَ ḏabbaḥa (he slaughtered), يُذَبِّح yuḏabbiḥ (he slaughters), and مَذْبَح maḏbaḥ (slaughterhouse). In each case, the absence of full glyphs for vowels makes the common root clearer, meaning that readers with knowledge of one word of the same root would have an easier time picking up on the similarity of meaning.

Application to non-Semitic languages

Many non-Semitic languages such as English could, theoretically, be written without vowels. It would be more difficult to read, but many words could be interpreted in context. This fact can be used to semi-bowdlerise offensive language, a practice known as disemvoweling. Many European languages, however, would lose grammatical information such as gender, case, and/or number. However, in English text the few inflections contain distinct consonants. It can be written without vowels and might still be clear, as in the first sentence of this paragraph: "Mny nn-Smtc lnggs sch s Nglsh, cld, thrtclly, b wrttn wtht vwls." This is a poor example, but it can be understood with effort.

In general, non-Semitic texts are often puzzling and ambiguous without their vowels, more so if the context and subject are unknown, because the consonant sequences for many word roots are not unique. For example, in English, "abate", "abet", "about", "abut", "bat", "bait", "bet", "beat", "beet", "bit", "bite", "bot", "boat", "boot", "bout", "but", and "byte" all reduce to "bt". Nevertheless, Indo-European languages can be written adequately using the impure abjads of Arabic and Hebrew, as with Persian orthography.[citation needed]

See also

- Numerology

- Abjad numerals

- Abugida

- Gematria, the Hebrew system of mystical numerology

- Shorthand (constructed writing systems that are structurally abjads)

Notes

- ^ Omniglot: Abjads / Consonant alphabets: "Abjads, or consonant alphabets, represent consonants only, or consonants plus some vowels. Full vowel indication (vocalisation) can be added, usually by means of diacritics, but this is not usually done." Accessed 22 May 2009.

- ^ Daniels, Peter T., et al. eds. The World's Writing Systems Oxford. (1996), p.4.

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2008) |

- Wright, W. (1971). A Grammar of the Arabic Language (3rd ed. ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. v. 1, p. 28. ISBN 0-521-09455-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

External links