Territorial disputes in the Persian Gulf: Difference between revisions

Shaibalahmar (talk | contribs) |

→Iranian claims on Bahrain: -- incorrect |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Iranian claims on Bahrain== |

==Iranian claims on Bahrain== |

||

[[Image:Bahrain map.png|thumb|Map of Bahrain]] |

[[Image:Bahrain map.png|thumb|Map of Bahrain]] |

||

Iran has often laid claim to Bahrain, based on its history of being a part of the Persian Empire and its seventeenth-century defeat of the [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] and its subsequent occupation of the Bahrain archipelago. The Arab [[House of Al-Khalifa|clan of the Al Khalifa]], which has been the ruling family of Bahrain since the eighteenth century, has many times shown loyalty to Iran when disputes with British colonizers were brought up by raising the Iranian flag on official buildings during the last years of the 19th century. Iran in return reserved a seat in the Iranian parliament in early 1900s for its 14 province which was Bahrain. The last [[shah]] of Iran, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]], raised the Bahrain issue with the British when they withdrew from areas east of the [[Suez Canal]], but he dropped his demand after a 1970 [[United Nations]]-backed and British executed questionnaire showed that Bahrainis overwhelmingly preferred independence to Iranian hegemony. However, it is important to note that Iran wanted a referendum sponsored by the UN in Bahrain so that the whole population would be able to vote on the future of the tiny Persian Gulf state, but the British refused and in turn suggested a method by which a British officer would give his report on the general inclinations of Bahrain's population after a general review. Since the majority of Bahrainis are Shiite, the British were not willing to put the future of Bahrain which is strategically important in the hands of the whole population. Due to this fact, the Bahrain issue was never really settled as some argue the UN sponsored report which was prepared by a British officer did not illustrate the true aspirations of the Bahrainis at the time and the role Britain played in this scenario had a major effect on the independence of the Persian Gulf state. In return for the withdrawal of its claim on Bahrain, the British agreed to fully leave the Greater and Lesser Tonbs to the Iranians, and have Abu Musa be administrated by Iran and U.A.E. mutually. |

Iran has often laid claim to Bahrain, based on its history of being a part of the Persian Empire and its seventeenth-century defeat of the [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] and its subsequent occupation of the Bahrain archipelago. The Arab [[House of Al-Khalifa|clan of the Al Khalifa]], which has been the ruling family of Bahrain since the eighteenth century, has many times shown loyalty to Iran when disputes with British colonizers were brought up by raising the Iranian flag on official buildings during the last years of the 19th century. Iran in return reserved a seat in the Iranian parliament in early 1900s for its 14 province which was Bahrain. The last [[shah]] of Iran, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]], raised the Bahrain issue with the British when they withdrew from areas east of the [[Suez Canal]], but he dropped his demand after a 1970 [[United Nations]]-backed and British executed questionnaire showed that Bahrainis overwhelmingly preferred independence to Iranian hegemony. However, it is important to note that Iran wanted a referendum sponsored by the UN in Bahrain so that the whole population would be able to vote on the future of the tiny Persian Gulf state, but the British refused and in turn suggested a method by which a British officer would give his report on the general inclinations of Bahrain's population after a general review. Since the majority of Bahrainis are Shiite, the British were not willing to put the future of Bahrain which is strategically important in the hands of the whole population. Due to this fact, the Bahrain issue was never really settled as some argue the UN sponsored report which was prepared by a British officer did not illustrate the true aspirations of the Bahrainis at the time and the role Britain played in this scenario had a major effect on the independence of the Persian Gulf state. In return for the withdrawal of its claim on Bahrain, the British agreed to fully leave the Greater and Lesser Tonbs to the Iranians, and have Abu Musa be administrated by Iran and U.A.E. mutually. |

||

==Iran and the United Arab Emirates== |

==Iran and the United Arab Emirates== |

||

Revision as of 14:58, 9 August 2011

This article needs to be updated. (November 2010) |

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (March 2008) |

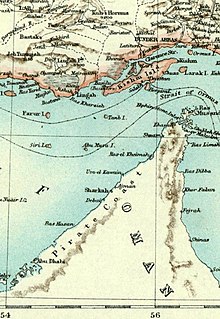

This article deals with territorial disputes between states of in and around the Persian Gulf in Southwestern Asia. These states include Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Oman.

Background

Before the oil era, the Persian Gulf states made little effort to delineate their territories. Members of Arab tribes felt loyalty to their tribe or shaykh and tended to roam across the Arabian desert according to the needs of their flocks. Official boundaries meant little, and the concept of allegiance to a distinct political unit was absent. Organized authority was confined to ports and oases. The delineation of borders began with the gradual encrochment of the Ottoman Empire on British interests in the Persian Gulf, leading to the Anglo-Turkish Conventions of 1913 and 1914. At the instigation of the British, the boundaries of Kuwait, Iraq and the province of Al-Hasa were delineated at Uqair in 1922. The signing of the first oil concessions in the 1930s brought a fresh impetus to the process. Inland boundaries had never properly demarcated, leaving opportunities for contention, especially in areas of the most valuable oil deposits. Until 1971, British-led forces maintained peace and order in the Gulf, and British officials arbitrated local quarrels. After the withdrawal of these forces and officials, old territorial claims and suppressed tribal animosities rose to the surface. The concept of the modern state—introduced into the Persian Gulf region by the European powers—and the sudden importance of boundaries to define ownership of oil deposits kindled acute territorial disputes.[1]

Iranian claims on Bahrain

Iran has often laid claim to Bahrain, based on its history of being a part of the Persian Empire and its seventeenth-century defeat of the Portuguese and its subsequent occupation of the Bahrain archipelago. The Arab clan of the Al Khalifa, which has been the ruling family of Bahrain since the eighteenth century, has many times shown loyalty to Iran when disputes with British colonizers were brought up by raising the Iranian flag on official buildings during the last years of the 19th century. Iran in return reserved a seat in the Iranian parliament in early 1900s for its 14 province which was Bahrain. The last shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, raised the Bahrain issue with the British when they withdrew from areas east of the Suez Canal, but he dropped his demand after a 1970 United Nations-backed and British executed questionnaire showed that Bahrainis overwhelmingly preferred independence to Iranian hegemony. However, it is important to note that Iran wanted a referendum sponsored by the UN in Bahrain so that the whole population would be able to vote on the future of the tiny Persian Gulf state, but the British refused and in turn suggested a method by which a British officer would give his report on the general inclinations of Bahrain's population after a general review. Since the majority of Bahrainis are Shiite, the British were not willing to put the future of Bahrain which is strategically important in the hands of the whole population. Due to this fact, the Bahrain issue was never really settled as some argue the UN sponsored report which was prepared by a British officer did not illustrate the true aspirations of the Bahrainis at the time and the role Britain played in this scenario had a major effect on the independence of the Persian Gulf state. In return for the withdrawal of its claim on Bahrain, the British agreed to fully leave the Greater and Lesser Tonbs to the Iranians, and have Abu Musa be administrated by Iran and U.A.E. mutually.

Iran and the United Arab Emirates

In 1971, after the British left the area Iranian forces reclaimed the islands of Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb, located at the mouth of the Persian Gulf between Iran and the UAE. The Iranians reasserted their historic claims to the islands, although the Iranians had been dislodged by the British in the late nineteenth century. Iran continued to hold the islands in 1993, and its action remained a source of contention with the UAE, which claimed authority by virtue of Britain's transfer of the islands to the emirates of Sharjah and Ras al-Khaimah. However, Britain had also agreed to give full authority to the Iranians in return for Iran's withdrawal of its claim on Bahrain. By late 1992, Sharjah and Iran had reached agreement with regard to Abu Musa, but Ras al-Khaimah had not reached a settlement with Iran concerning Greater Tunb and Lesser Tunb.[1] The claim by U.A.E however is not recognized internationally as at the time Iran and Britain agreed on the fate of the three Islands, the U.A.E was just in the midst of being formed as a result of British withdrawal from the area and therefore could not lay claim on any territory as it was not yet an official state.

Bahrain and Qatar

Another point of contention in the gulf was the Bahraini claim to Zubarah on the northwest coast of Qatar and to Hawar and the adjacent islands forty kilometers south of Zubarah, claims that stem from former tribal areas and dynastic struggles. The Al Khalifa had settled at Zubarah before driving the Iranians out of Bahrain in the eighteenth century. The Al Thani ruling family of Qatar vigorously dispute the Al Khalifa claim to the old settlement area now in Qatari hands as well as laying claim to the Bahraini-occupied Hawar and adjacent islands, a stone's throw from the mainland of Qatar but more than twenty kilometers from Bahrain. The simmering quarrel reignited in the spring of 1986 when Qatari helicopters removed and "kidnapped" workmen constructing a Bahraini coast guard station on Dibal Banks (Fasht ad Dibal), a reef off the coast of Qatar. Through Saudi Arabian mediation, the parties reached a fragile truce, whereby the Bahrainis agreed to remove their installations. However, in 1991 the dispute flared up again after Qatar instituted proceedings to let the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, Netherlands, decide whether it had jurisdiction. The two countries exchanged complaints that their respective naval vessels had harassed the other's shipping in disputed waters. The territorial dispute was solved by the ICJ in a 2001 decision. Bahrain kept the Hawar Islands and Qit'at Jaradah but dropped claims to Janan Island and Zubarah, while Qatar retained significant maritime areas and their resources. The agreement has furthered the goal of definitively establishing the border with Saudi Arabia and Saudi-led mediation efforts continue.[1]

Iraq and Kuwait

As one pretext for his invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Saddam Hussein revived a long-standing Iraqi claim to the whole of Kuwait based on Ottoman Empire boundaries. The Ottoman Empire exercised a tenuous sovereignty over Kuwait in the late nineteenth century, but the area passed under British protection in 1899. In 1932, Iraq informally confirmed its border with Kuwait, which had previously been demarcated by the British. In 1961, after Kuwait's independence and the withdrawal of British troops, Iraq reasserted its claim to the emirate based on the Ottomans' having attached it to Basra Province. British troops and aircraft were rushed back to Kuwait. A Saudi Arabian-led force of 3,000 from the League of Arab States (Arab League) that supported Kuwait against Iraqi pressure soon replaced them.[1]

The boundary issue again arose when the Baath Party came to power in Iraq after a 1963 revolution. The new government officially recognized the independence of Kuwait and the boundaries Iraq had accepted in 1932. Iraq nevertheless reinstated its claims to Bubiyan and Warbah islands in 1973, massing troops at the border. During the 1980-88 Iran–Iraq War, Iraq pressed for a long-term lease to the islands in order to improve its access to the gulf and its strategic position. Although Kuwait rebuffed Iraq, relations continued to be strained by boundary issues and inconclusive negotiations over the status of the islands.[1]

In August 1991, Kuwait charged that a force of Iraqis, backed by gunboats, had attacked Bubiyan but had been repulsed and many of the invaders captured. UN investigators found that the Iraqis had come from fishing boats and had probably been scavenging for military supplies abandoned after the Persian Gulf War. Kuwait was suspected of having exaggerated the incident to underscore its need for international support against ongoing Iraqi hostility.[1]

Al Buraimi

A particularly long and acrimonious disagreement involved claims over the Al Buraimi Oasis, disputed since the nineteenth century among tribes from Saudi Arabia, Abu Dhabi, and Oman. Although the tribes residing in the nine settlements of the oasis were from Oman and Abu Dhabi, followers of the Wahhabi religious movement that originated in what is now Saudi Arabia had periodically occupied and exacted tribute from the area. Oil prospecting began in the 1930s with British-backed the Iraq Petroleum Company creating subsidiary companies to explore and survey the area. In the late 1940s, Aramco survey parties began probing into Abu Dhabi territory with armed Saudi guards. Matters came to a head with a non-violent confrontation between Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia in 1949 known as the "Stobart incident", named after a British political officer of the time. In 1952, the Saudi Arabians sent a small constabulary force under Turki bin Abdullah Al Utayshan to occupy Hamasa, a village in the Buraimi Oasis. When arbitration efforts broke down in 1955, the British dispatched the Trucial Oman Scouts to expel the Saudi Arabian contingent. After the British withdrew from the Gulf, a settlement was reached between Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. Under the Treaty of Jeddah of 1974, Saudi Arabia recognized claims of Abu Dhabi and Oman to the oasis. In return, Abu Dhabi agreed to grant Saudi Arabia a land corridor to the Gulf at Khawr al Udayd and the oil from a disputed oil field. Some grazing and water rights remained in dispute.[1] In March 1990 Saudi Arabia settled her borders with Oman in an agreement that also provided for shared grazing rights and use of water resources. The exact details of the boundary were not disclosed. More recently, a dispute over the Dolphin Gas Project has renewed interest in the 1974 agreement.[2]

Musandam Peninsula

Earlier, the physical separation of the southern portion of Oman from its territory on the Musandam Peninsula was a source of friction between Oman and the various neighboring emirates that became the UAE in 1971. Differences over the disputed territory appeared to have subsided after the onset of the Iran–Iraq War in 1980.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Territorial Disputes." United Arab Emirates country study. Helem Chapin Metz, ed. Library of Congress, Federal Research Division (January 1993). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Morton, Michael Quentin, Buraimi: the Struggle for Power, Influence and Oil in South-eastern Arabia, to be published in 2012 by I.B. Tauris, ISBN 9781848858183