Population history of Egypt: Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

A study by Krings et al. from 1999 on [[mitochondrial DNA]] [[Cline (biology)|clines]] along the Nile Valley found that a [[Eurasian]] cline runs from [[Northern Egypt]] to [[Southern Sudan]].<ref name=" |

A study by Krings et al. from 1999 on [[mitochondrial DNA]] [[Cline (biology)|clines]] along the Nile Valley found that a [[Eurasian]] cline runs from [[Northern Egypt]] to [[Southern Sudan] and a Sub-Saharan cline from [[Southern Sudan] to [[Northern Egypt]].<ref name="kings">{{cite journal|year=1992|last=Kings|title=mtDNA Analysis of Nile River Valley Populations: Genetic Corridor or a Barrier to Migration?|first9=A|last9=Di Rienzo|first8=D|last8=Welsby|first7=C|last7=Simon|first6=L|last6=Chaix|first5=AK|last5=Malek|first4=H|last4=Geisert|first3=K|last3=Bauer|first2=AE|pmid=10090902|url=http://genapps.uchicago.edu/labweb/pubs/krings.pdf|last2=Salem|pmc=1377841|first1=T|volume=64|issue=5|pages=1116–76|journal=Am J Hum Genet.|doi=10.1086/302314}}</ref> An mtDNA study of modern Egyptians from the [[Kurna|Gurna]] region near [[Thebes]] in Southern Egypt revealed that [[Eurasian]] [[Recent_African_origin_of_modern_humans|Out of Africa]] haplogroups represented 79.4% of the population, with the remainder 20.6% being of [[Sub-Saharan]] origin. The oral tradition of the Gurna people indicates that they, like most modern day Egyptians, descend from the [[Ancient Egyptians]] <ref name="stevanovitch">{{cite journal|title=Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt |year=2004 |doi=10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x|url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/118745570/HTMLSTART|last=Stevanovitch|first1=A.|last2=Gilles|first2=A.|last3=Bouzaid|first3=E.|last4=Kefi|first4=R.|last5=Paris|first5=F.|last6=Gayraud|first6=R. P.|last7=Spadoni|first7=J. L.|last8=El-Chenawi|first8=F.|last9=Beraud-Colomb|first9=E.|journal=Annals of Human Genetics|volume=68|pages=23–39|pmid=14748828|issue=Pt 1}}</ref> |

||

A 2009 study on modern Upper (Southern) Egyptians using comparisons based on frequency and molecular data found that :<ref>Omran GA, et al: "Genetic variation of 15 autosomal STR loci in Upper (Southern) Egyptians"</ref> |

A 2009 study on modern Upper (Southern) Egyptians using comparisons based on frequency and molecular data found that :<ref>Omran GA, et al: "Genetic variation of 15 autosomal STR loci in Upper (Southern) Egyptians"</ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:37, 8 May 2012

The land currently known as Egypt has a long and involved population history. This is partly due to its geographical location at the crossroads of several major cultural areas: the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Sahara and East Africa. In addition Egypt has experienced several invasions during its long history, including by the Canaanites, the Libyans, the Nubians, the Assyrians, the Kushites, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans and the Arabs. The various conquests over time have made the relationship between Modern Egyptians and Ancient Egyptians a topic of investigation.

Prehistory

During the Paleolithic the Nile Valley was inhabited by various hunter gatherer populations. About 10,000 years ago the Sahara Desert had a wet phase. People from the surrounding areas moved from the Sahara, and evidence suggests that the populations of the Nile Valley reduced in size.[1] About 5,000 years ago the wet phase of the Sahara came to end. Saharan population retreated to the south towards the Sahel, and East towards the Nile Valley. It was these populations, in addition to Neolithic farmers from the Near East, that played a major role in the formation of the Egyptian state as they brought their food crops, sheep, goats and cattle to the Nile Valley.[1][2]

Predynastic Egypt

The Predynastic period dates to the end of the fourth millennium BC. From about 4800 to 4300BC the Merimde culture flourished in Lower Egypt.[3] This culture, among others, has links to the Levant.[4] The pottery of the Buto Maadi culture, best known from the site at Maadi near Cairo, also shows connections to the southern Levant.[5]

In Upper Egypt the predynastic Badarian culture was followed by the Naqada culture. The origins of these people is still not fully understood.

Biogeographic origin based on cultural data

Located in the extreme north-east corner of Africa, Ancient Egyptian society was at a crossroads between the African and Near Eastern regions. Early proponents of the Dynastic Race Theory based their hypothesis on the increased novelty and seemingly rapid change in Predynastic pottery and noted trade contacts between ancient Egypt and the Middle East.[6] This is no longer the dominant view in Egyptology, however the evidence on which it was based still suggests influence from these regions.[7] Fekri Hassan and Edwin et al. point to mutual influence from both inner Africa as well as the Levant.[8] However according to one author this influence seems to have had minimal impact on the indigenous populations already present.[9]

One author has stated that the Naqada phase of Predynastic Egyptians in Upper Egypt shared an almost identical culture with A-group peoples of the Lower Sudan.[10] Based in part on the similarities at the royal tombs at Qustul, some scholars have even proposed an Egyptian origin in Nubia among the A-group.[11][12] In 1996 Lovell and Prowse reported the presence of individual rulers buried at Naqada in what they interpreted to be elite, high status tombs, showing them to be more closely related morphologically to populations in Northern Nubia than those in Southern Egypt.[13] Most scholars however, have rejected this hypothesis and cite the presence of royal tombs that are contemporaneous with that of Qustul and just as elaborate, together with problems with the dating techniques.[14]

The language of the Nubian people is one of the Nilo-Saharan languages, whereas the language of the Egyptian people was one of the Afro-Asiatic languages.

Toby Wilkinson, in his book "Genesis of the Pharaohs", proposes an origin for the Egyptians somewhere in the Eastern Desert.[15] He presents evidence that much of predynastic Egypt duplicated the traditional African cattle-culture typical of Southern Sudanese and East African pastoralists of today. Kendall agrees with Wilkinson's interpretation that ancient rock art in the region may depict the first examples of the royal crowns, while also pointing to Qustul in Nubia as a likely candidate for the origins of the white crown, being that the earliest known example of it was discovered in this area.

There is also evidence that sheep and goats were introduced into Nabta from Southwest Asia about 8,000 years ago.[2] There is some speculation that this culture is likely to be the predecessor of the Egyptians, based on cultural similarities and social complexity which is thought to be reflective of Egypt's Old Kingdom.[16][17]

DNA studies

Attempts to extract ancient DNA or aDNA from Ancient Egyptian remains have yielded mainly Eurasian DNA types from the Dakleh Oasis cemetery site (from Southern Egypt), and they show a considerable increase in the amount of Sub Saharan mitchondrial DNA only over the past 2,000 years, suggesting that within this timeframe there was more migration from Sub-Saharan Africa to the Nile Valley than from Eurasia to the Nile Valley.[18] One successful study was performed on ancient mummies of the 12th Dynasty, by Paabo and Di Rienzo, which identified multiple lines of descent, which originated in sub-Saharan Africa.[19] Contamination from handling and intrusion from microbes have also created obstacles to recovery of Ancient DNA.[18] Consequently most DNA studies have been carried out on modern Egyptian populations with the intent of learning about the influences of historical migrations on the population of Egypt.[20][21][22][23]

DNA studies on modern Egyptians

Egypt has experienced several invasions during its history. However, these do not seem to account for more than about 10% overall of current Egyptians ancestry when the DNA evidence of the ancient mitochondrial DNA and modern Y chromosomes is considered. While Ivan van Sertima argue that the Egyptians were primarily Africoid before the many conquests of Egypt diluted the Africanity of the Egyptian people,[24] other scholars such as Frank Yurco believe that Modern Egyptians are largely representative of the ancient population, and the DNA evidence appears to support this view.[25]

In general, various DNA studies have found that the gene frequencies of modern North African populations are intermediate between those of the Horn of Africa and Eurasia,[26] though possessing a greater genetic affinity with the populations of Eurasia than they do with Africa.[27][27][28][29][30][31]

Luis, Rowold et al. found that the diverse NRY haplotypes observed in a population of mixed Arabs and Berbers found that the majority of haplogroups, about 60.5% were of Eurasian origin. They found that markers signaling the Neolithic invasion from the Middle East constitute the predominant component. The remaining 39.5% were clades that belonged to Haplogroup E1b1b, found predominantly amongst the populations of the Horn of Africa and the Mediterranean basin. E1b1b and its derivatives are characteristic of some Afro-Asiatic speakers and is believed to have originated in either the Near East, North Africa, or the Horn of Africa.[32][33]

A study by Krings et al. from 1999 on mitochondrial DNA clines along the Nile Valley found that a Eurasian cline runs from Northern Egypt to [[Southern Sudan] and a Sub-Saharan cline from [[Southern Sudan] to Northern Egypt.[34] An mtDNA study of modern Egyptians from the Gurna region near Thebes in Southern Egypt revealed that Eurasian Out of Africa haplogroups represented 79.4% of the population, with the remainder 20.6% being of Sub-Saharan origin. The oral tradition of the Gurna people indicates that they, like most modern day Egyptians, descend from the Ancient Egyptians [35]

A 2009 study on modern Upper (Southern) Egyptians using comparisons based on frequency and molecular data found that :[36]

No differences were observed in comparison with a general Caucasian population from Cairo in any of the nine loci compared, or with Egyptian Coptic Christians from Cairo…Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) based on pair-wise FST genetic distances of Upper Egyptian and other diverse global populations. OCE, Oceanian; ME, Middle Eastern; NAF, North African; EAS, East Asian; SSA, sub-Saharan African; UEGY, Upper Egyptian; SAS, South Asian; EUR, European. The figure shows that Oceania and American populations are very distant from Upper Egyptians (marked by a grey triangle) and other populations. The Upper Egyptian population is closer to the Middle Eastern, North African, South Asian and European populations than others.

The results of these genetic studies is consistent with the historical record, which records significant bidirectional contact between Egypt and Nubia, and the Levant/Near East within the last few thousand years, but with general population continuity from the Early Dynastic period up to the modern day era.[37][38] Swiss scientists at Zurich-based DNA genealogy centre, iGENEA, reconstructed DNA profile of Tutankhamun, based on a film that was made for the Discovery Channel, which showed that Tutankhamun has Haplogroup R1b1a2, to which more then 50% of European men belong.[39] However, this DNA group also shows up in parts of northern Africa, particularly Algeria, where tests have found it in 11.8% of subjects.[40] The R1b haplogroup is also found in central Africa around Chad and Cameroon,[41] but the Chadic-speaking area in Africa is dominated by the branch known as R1b1c (R-V88).[42]

In December 2011, the private genetics research company DNA Tribes released an analysi, based on 8 forensic autosomal STR markers. The study in particular analyzed the DNA of the Amarna Pharaohs and reported that "Average MLI scores in Table 1 indicate the STR profiles of the Amarna mummies would be most frequent in present day populations of several African regions" [43]

Anthropometric indicators

Craniofacial criteria

Craniofacial criteria are no longer universally accepted as reliable indicators of population grouping or ethnicity. In 1912 Franz Boas demonstrated that cranial shape is heavily influenced by environmental factors, and can change within a few generations if conditions change, and therefore cranial measurements cannot be a reliable indicator of inherited influences such as ethnicity.[44] This conclusion was supported in 2003 in a paper by Gravlee, Bernard and Leonard.[45][46] A study by Beals, Smith, and Dodd (1984) found that "race" and cranial variation had low correlations, and that cranial variation was instead strongly correlated with climate variables.[47] This view is also supported by Kemp.[48] Other studies have shown that the typical cranial shapes of some African (Sudanic and Ethiopic), Arab and Berber ethnic groups are largely the same.[49][50]

A craniofacial study by C. Loring Brace et al. (1993) concluded that: "The Predynastic of Upper Egypt and the Late Dynastic of Lower Egypt are more closely related to each other than to any other population. As a whole, they show ties with the Sub Saharan, North Africa,the Near East, modern Africae, and, more remotely, India, but not at all with Europe, eastern Asia, Oceania, or the New World."[51] He also commented,"We conclude that the Egyptians have been in place since back in the Pleistocene and have been largely unaffected by either invasions or migrations. As others have noted, Egyptians are Egyptians, and they were so in the past as well.". The results of this study however have been criticized and contradicted by the works of other anthropologists such as S.O.Y. Keita and Sonia Zakrzewski.

A survey cited by Kemp (2005) of pooled ancient Egyptian crania spanning all time periods found that the Egyptian population as a whole clusters more closely to modern Egyptians than to other groups, but apart from modern Egyptians, they cluster closest to Nubian and "Ethiopic" populations than they do to Middle Easterners or Europeans. In Kemp's unpooled dendrogram it details that the Pre-Dynastic Egyptians (El Bardi and Naqada) samples cluster closest to ancient Nubians and modern Ethiopic populations, and conversely that Late Kingdom and modern Egyptians cluster with Middle Eastern and modern European populations. Kemp also noted that Egypt conquered and settled Nubia beginning in the 1st Dynasty.[52]

Anthropologist Nancy Lovell states the following:

"There is now a sufficient body of evidence from modern studies of skeletal remains to indicate that the ancient Egyptians, especially southern Egyptians, exhibited physical characteristics that are within the range of variation for ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Sub Sahara and tropical Africa.. In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas." "must be placed in the context of hypotheses informed by archaeological, linguistic, geographic and other data. In such contexts, the physical anthropological evidence indicates that early Nile Valley populations can be identified as part of an African lineage, but exhibiting local variation. This variation represents the short and long term effects of evolutionary forces, such as gene flow, genetic drift, and natural selection, influenced by culture and geography." [53]

This view was also shared by the late Egyptologist, Frank Yurco.[54]

A 2005 study by Keita of predynastic Badarian (Southern Egyptian) crania found that the Badarian samples cluster more closely with East African (Ethiopic) samples than they do with Northern European (Berg and Norse) samples, though importantly no Asian and Southern Africa samples were included in the study.[55] Keita has also said that the predyastic crania are different to the lower Egyptian samples, which display a mean part way between modern Sub Saharans Africans and Ethiopians.

Sonia Zakrzewski in 2007 noted that population continuity occurs over the Egyptian Predynastic into the Greco-Roman periods, and that a relatively high level of genetic differentiation was sustained over this time period. She concluded therefore that the process of state formation itself may have been mainly an indigenous process, but that it may have occurred in association with in-migration, particularly during the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods.[56]

In 2008 Keita found that the early predynastic groups in Southern Egypt were similar craniometrically to Nile valley groups of Ethiopic extraction, and as a whole the dynastic Egyptians (includes both Upper and Lower Egyptians) show much closer affinities more southerly Northeast African populations. He also concluded that more material is needed to make a firm conclusion about the relationship between the early Holocene Nile valley populations and later ancient Egyptians.[57]

Limb ratios

Anthropologist C. Loring Brace points out that limb elongation is "clearly related to the dissipation of metabolically generated heat" in areas of higher ambient temperature. He also stated that "skin color intensification and distal limb elongation is apparent wherever people have been long-term residents of the tropics". He also points out that the term "super negroid" is inappropriate, as it is also applied to non negroid populations. These features have been observed among Egyptian samples.[58] According to Robins and Shute the average limb elongation ratios among ancient Egyptians is higher than that of modern West Africans who reside much closer to the equator. Robins and Shute therefore term the ancient Egyptians to be "super-negroid" but state that although the body plans of the ancient Egyptians were closer to those of modern negroes than for modern whites, "this does not mean that the ancient Egyptians were negroes".[59] Anthropologist S.O.Y. Keita criticized Robins and Shute, stating they do not interpret their results within an adaptive context, and stating that they imply "misleadingly" that early southern Egyptians were not a "part of the Saharo-tropical group, which included Negroes".[60] Gallagher et al. also points out that "body proportions are under strong climatic selection and evidence remarkable stability within regional lineages".[61] Zakrzewski (2003) studied skeletal samples from the Badarian period to the Middle Kingdom. She confirmed the results of Robins and Shute that Ancient Egyptians in general had "tropical body plans" but that their proportions were actually "super-negroid".[62]

Trikhanus (1981) found Egyptians to plot closest to tropical Africans and not Mediterranean Europeans residing in a roughly similar climatic area.[63] A more recent study compared ancient Egyptian osteology to that of African-Americans and White Americans, and found that the stature of the Ancient Egyptians was more similar to the stature of African-Americans, although it was not identical:[64]

Our results confirm that, although ancient Egyptians are closer in body proportion to modern American Blacks than they are to American Whites, proportions in Blacks and Egyptians are not identical.

Dental morphology

A 2006 bioarchaeological study on the dental morphology of ancient Egyptians by Prof. Joel Irish shows dental traits characteristic of current indigenous North Africans and to a lesser extent Middle Eastern and southern European populations, but not at all to Sub-Saharan populations. Among the samples included in the study is skeletal material from the Hawara tombs of Fayum, (from the Roman period) which clustered very closely with the Badarian series of the predynastic period. All the samples, particularly those of the Dynastic period, were significantly divergent from a neolithic West Saharan sample from Lower Nubia. Biological continuity was also found intact from the dynastic to the post-pharaonic periods. According to Irish:

[The Egyptian] samples [996 mummies] exhibit morphologically simple, mass-reduced dentitions that are similar to those in populations from greater North Africa (Irish, 1993, 1998a–c, 2000) and, to a lesser extent, western Asia and Europe (Turner, 1985a; Turner and Markowitz, 1990; Roler, 1992; Lipschultz, 1996; Irish, 1998a).[65]

Anthropologist Shomarka Keita takes issue with the suggestion of Irish that Egyptians and Nubians were not primary descendants of the African epipaleolithic and Neolithic populations. Keita also criticizes him for ignoring the possibility that the dentition of the ancient Egyptians could have been caused by "in situ microevolution" driven by dietary change, rather than by racial admixture.[66] However Keita himself has observed population continuity from the Pleistocene to the present in modern Egyptians.

The language element

Ancient Egyptian languages are classified into six major chronological divisions; Archaic Egyptian, Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, Demotic Egyptian, and Coptic, the latter of which was still used as a working language until the 18th Century AD, and is still used as a liturgical language by Egyptian Copts to this day.[67]

Origins

The Ancient Egyptian language has been classified as a member of the Afro-Asiatic language family. There is no agreement on when and where these languages originated, though the language is generally believed to have originated somewhere in or near the region stretching from the Levant in the Near East to northern Kenya, and from the Eastern Sahara in North Africa to the Red Sea, or Southern Arabia, Ethiopia and Sudan.[68][69][70][71][72]

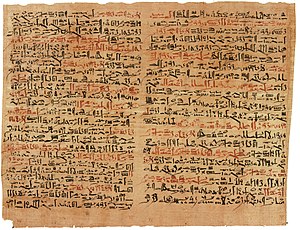

Scripts

Most surviving texts in the Egyptian language are primarily written in the Hieroglyphic script. However, the Hieratic script was used in parallel although mostly reserved for priests[73] but also for magical purposes and administrative and legal documents. This script used cursive and simplified forms of the Hieroglyphic writing to ease and speed writing. It was mostly written on papyrus, wood, leather and ostraca.[74] It lasted until the ninth century BCE when it was replaced by the "Abnormal Hieratic" in southern Egypt.[74] Another third script was the Demotic which was developed in Lower Egypt during the later part of the 25th Dynasty.

References

- ^ a b Ancient Egyptian Origins

- ^ a b http://www.comp-archaeology.org/WendorfSAA98.html

- ^ Bogucki, Peter I. (1999). The origins of human society. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 355. ISBN 1-57718-112-3.

- ^ Josef Eiwanger: Merimde Beni-salame, In: Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Compiled and edited by Kathryn A. Bard. London/New York 1999, p. 501-505

- ^ Jürgen Seeher. Ma'adi and Wadi Digla. in: Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Compiled and edited by Kathryn A. Bard. London/New York 1999, 455-458

- ^ Hoffman. "Egypt before the pharaohs: the prehistoric foundations of Egyptian civilization", pp267

- ^ Redford, Egypt, Israel, p. 17.

- ^ Edwin C. M et. al, "Egypt and the Levant", pp514

- ^ Toby A.H. Wilkinson. " Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security", pp.15

- ^ Hunting for the Elusive Nubian A-Group People - by Maria Gatto, archaeology.org

- ^ Egypt and Sub-Saharan Africa: Their Interaction - Encyclopedia of Precolonial Africa, by Joseph O. Vogel, AltaMira Press, (1997), pp. 465-472

- ^ Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), pp. 15-26

- ^ Tracy L. Prowse, Nancy C. Lovell. Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 101, Issue 2, October 1996, Pages: 237-246

- ^ Wegner, J. W. 1996. Interaction between the Nubian A-Group and Predynastic Egypt: The Significance of the Qustul Incense Burner. In T. Celenko, Ed., Egypt in Africa: 98-100. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art/Indiana University Press.

- ^ Genesis of the Pharaohs: Genesis of the ‘Ka’ and Crowns? - Review by Timothy Kendall, American Archaeologist

- ^ Ancient Astronomy in Africa

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (2001). Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. Springer. p. 525. ISBN 0-306-46612-0.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt By Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert pp 278-279

- ^ Paabo, S., and A. Di Rienzo, A molecular approach to the study of Egyptian history. In Biological Anthropology and the Study of Ancient Egypt. V. Davies and R. Walker, eds. pp. 86-90. London: British Museum Press. 1993

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita & A. J. Boyce, S. O. Y.; Boyce, A. J. (Anthony J.) (June 2009). "Genetics, Egypt, and History: Interpreting Geographical Patterns of Y Chromosome Variation" (PDF). History in Africa. 32 (1): 221. doi:10.1353/hia.2005.0013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Shomarka Keita (2005), S. O. Y. (2005). "Y-Chromosome Variation in Egypt" (PDF). African Archaeological Review. 22 (2): 61. doi:10.1007/s10437-005-4189-4. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/43700541894 |43700541894 [[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite journal}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Keita, S.O.Y. (2005). "History in the Interpretation of the Pattern of p49a,f TaqI RFLP Y-Chromosome Variation in Egypt" (PDF). American Journal of Human Biology. 17 (5): 559–67. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20428. PMID 16136533.

- ^ Shomarka Keita: What genetics can tell us

- ^ Egypt, Child of Africa. 1994. ISBN 1-56000-792-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review" in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, eds. Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. p. 62-100

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, History and Geography of Human Genes, The intermediacy of North Africa and to lesser extent East Africa between Africa and Europe is apparent

- ^ a b Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., P. Menozzi, and A. Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Bosch, E.; et al. (1997). "Population history of north Africa: evidence from classical genetic markers". Human Biology. 69 (3): 295–311.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help) - ^ Arredi B, Poloni E, Paracchini S, Zerjal T, Fathallah D, Makrelouf M, Pascali V, Novelletto A, Tyler-Smith C (2004). "A predominantly neolithic origin for Y-chromosomal DNA variation in North Africa". Am J Hum Genet. 75 (2): 338–45. doi:10.1086/423147. PMC 1216069. PMID 15202071.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manni F, Leonardi P, Barakat A, Rouba H, Heyer E, Klintschar M, McElreavey K, Quintana-Murci L (2002). "Y-chromosome analysis in Egypt suggests a genetic regional continuity in Northeastern Africa". Hum Biol. 74 (5): 645–58. doi:10.1353/hub.2002.0054. PMID 12495079.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cavalli-Sforza. "Synthetic maps of Africa". The History and Geography of Human Genes. ISBN 0-691-08750-4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)The present population of the Sahara is Caucasoid in the extreme north, with a fairly gradual increase of Negroid component as one goes south - ^ The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations – Luis; Rowold; Regueiro; Caeiro; Cinnioğlu; Roseman; Underhill; Cavalli-Sforza; and Herrera. – see http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1182266

- ^ Underhill (2002), Bellwood and Renfrew, ed., Inference of Neolithic Population Histories using Y-chromosome Haplotypes, Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, ISBN 1-902937-20-1

- ^ Kings, T; Salem, AE; Bauer, K; Geisert, H; Malek, AK; Chaix, L; Simon, C; Welsby, D; Di Rienzo, A (1992). "mtDNA Analysis of Nile River Valley Populations: Genetic Corridor or a Barrier to Migration?" (PDF). Am J Hum Genet. 64 (5): 1116–76. doi:10.1086/302314. PMC 1377841. PMID 10090902.

- ^ Stevanovitch, A.; Gilles, A.; Bouzaid, E.; Kefi, R.; Paris, F.; Gayraud, R. P.; Spadoni, J. L.; El-Chenawi, F.; Beraud-Colomb, E. (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 1): 23–39. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x. PMID 14748828.

- ^ Omran GA, et al: "Genetic variation of 15 autosomal STR loci in Upper (Southern) Egyptians"

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

kringswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lucotte, G.; Mercier, G. (2001). "Brief communication: Y-chromosome haplotypes in Egypt" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (1): 63–6. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10190. PMID 12687584.

- ^ Half of European men share King Tut's DNA. Reuters, 1 August 2011. Retrieved on 6 August 2011

- ^ Robino; Crobu, F; Di Gaetano, C; Bekada, A; Benhamamouch, S; Cerutti, N; Piazza, A; Inturri, S; Torre, C; et al. (2008). "Analysis of Y-chromosomal SNP haplogroups and STR haplotypes in an Algerian population sample". Journal International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (3): 251–5. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0203-5. PMID 17909833.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Cruciani, F; Santolamazza, P; Shen, P; Macaulay, V; Moral, P; Olckers, A; Modiano, D; Holmes, S; Destro-Bisol, G (2002). "A back migration from Asia to sub-Saharan Africa is supported by high-resolution analysis of human Y-chromosome haplotypes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1197–214. doi:10.1086/340257. PMC 447595. PMID 11910562., pp. 13–14

- ^ Cruciani; Trombetta, B; Sellitto, D; Massaia, A; Destro-Bisol, G; Watson, E; Beraud Colomb, E; Dugoujon, JM; Moral, P; et al. (2010). "Human Y chromosome haplogroup R-V88: a paternal genetic record of early mid Holocene trans-Saharan connections and the spread of Chadic languages". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (7): 800–7. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.231. PMC 2987365. PMID 20051990.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Digest DNA Tribes® Digest January 1, 2012 Copyright © 2012 DNA Tribes® . All rights reserved, accessed March 04, 2012.

- ^ Boas, "Changes in Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants" (American Anthropologist 14:530–562, 1912)

- ^ http://www.anthro.fsu.edu/people/faculty/CG_pubs/gravlee03b.pdf

- ^ Clarence C. Gravlee, H. Russell Bernard, and William R. Leonard find in "Heredity, Environment, and Cranial Form: A Re-Analysis of Boas’s Immigrant Data" (American Anthropologist 105[1]:123–136, 2003)

- ^ How Caucasoids Got Such Big Crania and How They Shrank, by Leonard Lieberman

- ^ Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization, by Barry J. Kemp pg 47

- ^ "The races of man: an outline of anthropology and ethnography", by Joseph Deniker, pg 432

- ^ "Papers on inter-racial problems", by Gustav Spiller, pg 24

- ^ Brace et al., 'Clines and clusters versus "race"' (1993)

- ^ Kemp, Barry (2005). "Who were the Ancient Egyptians". Egypt: Anatomy of a civilization. p. 52. ISBN 0-415-01281-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Nancy C. Lovell, " Egyptians, physical anthropology of," in Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, ed. Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, ( London and New York: Routledge, 1999). pp 328-332)

- ^ Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review" in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, eds. Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. pp. 62–100

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita (2005), S. O. Y. (2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers, From El-Badari, Aboriginals or "European" Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data" (PDF). Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ http://wysinger.homestead.com/zakrzewski_2007.pdf

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y. "Temporal Variation in Phenetic Affinity of Early Upper Egyptian Male Cranial Series", Human Biology, Volume 80, Number 2 (2008)

- ^ Brace CL, Tracer DP, Yaroch LA, Robb J, Brandt K, Nelson AR (1993). Clines and clusters versus "race:" a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile. Yrbk Phys Anthropol 36:1–31'.

- ^ Predynastic egyptian stature and physical proportions - Robins, Gay. Human Evolution, Volume 1, Number 4 / August, 1986

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita. Studies and Comments of Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa, 20: 129-154 (1993)

- ^ Gallagher et al. "Population continuity, demic diffusion and Neolithic origins in central-southern Germany: The evidence from body proportions.", Homo. Mar 3 (2009)

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (2003). "Variation in Ancient Egyptian Stature and Body Proportions" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 219–29. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223. PMID 12772210.

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita, History in Africa, 20: 129-154 (1993)

- ^ Raxter et al. "Stature estimation in ancient Egyptians: A new technique based on anatomical reconstruction of stature (2008).

- ^ Irish pp. 10-11

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita, S. O. Y. (1995). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships" (PDF). International Journal of Anthropology. 10 (2–3): 107. doi:10.1007/BF02444602.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. (1999). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 274. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Blench R (2006) Archaeology, Language, and the African Past, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0-7591-0466-2, 978-0-7591-0466-2, http://books.google.be/books?id=esFy3Po57A8C

- ^ Ehret C, Keita SOY, Newman P (2004) The Origins of Afroasiatic a response to Diamond and Bellwood (2003) in the Letters of SCIENCE 306, no. 5702, p. 1680 doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c http://wysinger.homestead.com/afroasiatic_-_keita.pdf

- ^ Bernal M (1987) Black Athena: the Afroasiatic roots of classical civilization, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-3655-3, 9780813536552. http://books.google.be/books?id=yFLm_M_OdK4C

- ^ Bender ML (1997), Upside Down Afrasian, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 50, pp. 19-34

- ^ Militarev A (2005) Once more about glottochronology and comparative method: the Omotic-Afrasian case, Аспекты компаративистики - 1 (Aspects of comparative linguistics - 1). FS S. Starostin. Orientalia et Classica II (Moscow), p. 339-408. http://starling.rinet.ru/Texts/fleming.pdf

- ^ James, T. G. H. Pharaoh's People: Scenes from Life in Imperial Egypt. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 135. ISBN 1-84511-335-7.

- ^ a b David, Ann Rosalie (1999). Handbook to life in ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press US. pp. 193–194. ISBN 0-19-513215-7.

Further reading

- Morant, G. M. (1925). "A study of Egyptian craniology from prehistoric to Roman times". Biometrika. 17 (1/2). Biometrika: 1–52. JSTOR 2332021.

- MacIver (1905). "chapter 9". The Ancient Races of the Thebaid.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Strouhal, Eugen (1971). "Evidence of the Early Penetration of Negroes into Prehistoric Egypt". Journal of African History. 12 (1). Cambridge University Press: 1–9. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000037. JSTOR 180563.

- Keita, Shomarka (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships" (PDF). History in Africa.