Vertebral augmentation: Difference between revisions

→Society and culture: AAOS recommendation against |

Updated the information on the page...it was very out of date. |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Vertebroplasty''' and '''kyphoplasty''' are similar [[medicine|medical]] spinal procedures where bone cement is injected through a small hole in the skin ([[percutaneous]]ly) into a fractured [[vertebra]] with the goal of relieving the pain of [[compression fracture|vertebral compression fractures]] (VCF). |

'''Vertebroplasty''' and '''kyphoplasty''' are similar [[medicine|medical]] spinal procedures where bone cement is injected through a small hole in the skin ([[percutaneous]]ly) into a fractured [[vertebra]] with the goal of relieving the pain of [[compression fracture|vertebral compression fractures]] (VCF). |

||

There are 1587 vertebral augmention articles in the English language. The most recent meta-analysis published in 2012 by Dr. Ioannis Papanastassiou is the first meta-analysis of only Level I and Level II date and evaluated 27 studies including eight randomized studies. The authors concluded after analyzing this body of literature in great detail that both Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty provide significant pain relief and 50% reduced rate of additional fracture over nonsurgical management. They also concluded that BKP has better anatomy restoration, and may be more beneficial than VP for improving quality of life (QOL) and disability. |

|||

There were two randomized controlled trials published in 2009 by Dr. David Kallmes and Dr. Rachael Buchbinder that concluded that Vertebroplasty was no better than a sham treatment at relieving the pain associate with vertebral compression fractures. This created controversy as the conclusions were not consistent with clinicians experience with this procedure. A meta-analysis published in 2012 by Dr. Ming-Min Shi was the first to include all available prospective evidence, including six of which were randomized control trials RCT’s. This meta-analysis concluded that compared with nonsurgical management (NSM), Vertebroplasty was more effective in relieving pain and in improving the QOL for patients with VCFs. The 2009 articles published in the New England Journal of Medicine have since been discredited due to the bulk of high quality data that has found Vertebroplasty to be safe and effective and because of design and excution problems with these articles. Some of the primary criticisms include that the 2009 triald were underpowered, suffered from selection bias, had unclear clinical and imaging diagnostic criteria for inclusion (i.e. no requirement for Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging or nuclear bone scanning for diagnosing the fractures), that there was no description of a clinical exam used to determine if the pain came from a vertebral fracture or from another issue, and that the sham was actually an injection of local anesthetic into the area around the spine. Despite all of these limiting factors, when analyzing the structure and execution of the trial itself, if the same response rate for the 131 patients that were included had been carried out for the originally intended 250 patients, vertebroplasty would have been found to be significantly better than sham treatement at a p-value of < 0.01. Even with the 131 patients, if one patient had a different response (i..e a favorable response in the VP group or an unfavorable response in the sham group), VP would have been found to be significantly better than sham with a p-value of < 0.04. Given the near equivocal nature of this information and the presence of a large body of data with a different conclusion these studies should not be considered within a larger perspective. |

|||

If the highest quality portion of that literature on Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty is analyzed the conclusions that can be drawn are that vertebral augmentation was significantly better than nonsurgical management for decreasing pain and if the fracture was treated in the first seven weeks, the pain reduction is better. This analysis also shows significantly less additional fractures for those patients treated with vertebral augmentation rather than those treated with nonsurgical management and those patients treated with Kyphoplasty had a significantly better improvement in their quality of life than those treated with Vertebroplasty. The data also shows a significantly higher mortality in those patients treated with nonsurgical management as compared with those patients treated with vertebral augmentation emphasizes the importance of offering the treatment most likely to benefit the patient. |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Vertebroplasty had been performed as an open procedure for many decades to secure pedicle screws and fill tumorous voids. However, the results were not always worth the risk involved with an [[Invasiveness of surgical procedures#Open surgery|open procedure]], which was the reason for the development of [[percutaneous]] vertebroplasty. |

|||

The first percutaneous vertebroplasty was performed in 1984 at the University Hospital of Amiens, France to |

The first percutaneous vertebroplasty was performed in 1984 at the University Hospital of Amiens, France to treat an aggressive vertebral hemangioma [[spinal tumor]]. A report of this and 6 other patients was published in 1987 and it was introduced in the United States in the early 1990s. Initially, the treatment was used primarily for tumors in Europe and VCF in the United States, although the distinction has largely gone away since then.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Mathis |editor1-first=John M. |editor2-last=Deramond |editor2-first=Hervé |editor3-last=Belkoff |editor3-first=Stephen M. |title=Percutaneous Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty |edition=2nd |year=2006 |origyear=First edition published 2002 |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media]] |isbn=0-387-29078-8 |pages=3–5}}</ref> |

||

== Effectiveness == |

== Effectiveness == |

||

Out of the 27 articles on Vertebral Augmentation (including Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty) identified by Papanastassiou, et al in their summary of all Level I and Level II data, 18 of the studies involved Kyphoplasty. All of these studies by definition included over 20 patients and the Kyphoplasty articles included the FREE trial with 300 patients and a trial comparing Kyphoplasty and Vertebroplasty with 100 patients. The conclusion of Papanastassiou regarding Kyphoplasty was that it decreased pain to a greater degree than Vertebroplasty (5.07 vs 4.55 points on the VAS) and resulted in significantly better improvement in quality of life than both Vertebroplasty and non-surgical management. This meta-analysis was taken from 1587 articles on vertebral augmentation, more articles than in any other area of spine. |

|||

The effectiveness of vertebroplasty is controversial. Two randomized and blinded trials found no benefit however they have been faulted for not looking at people with acute [[vertebral fracture]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Gangi|first=A|coauthors=Clark, WA|title=Have recent vertebroplasty trials changed the indications for vertebroplasty?|journal=Cardiovascular and interventional radiology|date=2010 Aug|volume=33|issue=4|pages=677–80|pmid=20523998|doi=10.1007/s00270-010-9901-3}}</ref> Some have suggested that this procedure only be done in those with fractures less than 6 weeks old (which was not the population of these two trials).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Clark|first=WA|coauthors=Diamond, TH, McNeil, HP, Gonski, PN, Schlaphoff, GP, Rouse, JC|title=Vertebroplasty for painful acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures: recent Medical Journal of Australia editorial is not relevant to the patient group that we treat with vertebroplasty.|journal=The Medical journal of Australia|date=2010-03-15|volume=192|issue=6|pages=334–7|pmid=20230351}}</ref> |

|||

A recent meta-analysis on Vertebroplasty by Dr. Ming-Min Shi which was the first to include all the available prospective evidence, including nine prospective controlled trials (six of which were RCT’s) concluded that compared with NSM, VP was more effective in relieving pain and in improving the QOL for patients with vertebral compression fractures. This meta-analysis was also substantially larger, quadrupling the sample size compared with previous meta-analysis. |

|||

=== NEJM Articles === |

|||

Two studies published in ''[[The New England Journal of Medicine]]'' in 2009 found no benefit to vertebroplasty for compression fractures when compared to a sham procedure :<ref name="UPI">"Studies question impact of vertebroplasty." Aug. 6, 2009: UPI.com</ref> |

|||

* In a multicenter, prospective double-blinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 131 participants who were patients with one or two painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures, vertebroplasty did not result in greater improvement than a sham procedure in overall pain, physical functioning, or quality of life at 3 or 6 months after treatment.<ref name="Kallmes">{{cite journal|last=Kallmes|first=DF|coauthors=Comstock, BA, Heagerty, PJ, Turner, JA, Wilson, DJ, Diamond, TH, Edwards, R, Gray, LA, Stout, L, Owen, S, Hollingworth, W, Ghdoke, B, Annesley-Williams, DJ, Ralston, SH, Jarvik, JG|title=A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures.|journal=The New England Journal of Medicine|date=2009-08-06|volume=361|issue=6|pages=569–79|pmid=19657122|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0900563|pmc=2930487}}</ref> [[Jeffrey Jarvik]] of the [[University of Washington Medical Center|University of Washington]] said his study, funded by the [[National Institutes of Health]], found vertebroplasty had no detectable benefit when compared with procedures that only mimicked such procedures. He advises that "vertebroplasty should not be done any longer, unless it's in the setting of a study."{{Citation needed|date=July 2011}} |

|||

* In a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 78 participants with osteoporotic vertebral ''compression fractures'', patients who underwent vertebroplasty had improvements in pain and disability measures that were similar to those in patients who underwent a sham procedure.<ref name="Buchbinder">{{cite journal|last=Buchbinder|first=R|coauthors=Osborne, RH, Ebeling, PR, Wark, JD, Mitchell, P, Wriedt, C, Graves, S, Staples, MP, Murphy, B|title=A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures.|journal=The New England Journal of Medicine|date=2009-08-06|volume=361|issue=6|pages=557–68|pmid=19657121|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0900429}}</ref> University of Virginia radiologist Avery Evans said his study, which was funded by the Australian government and Cook Medical Inc., found vertebroplasty and sham procedures offered patients nearly identical pain relief.<ref name="UPI" /> |

|||

Several case reports and unblinded studies initially suggested that vertebroplasty provided effective relief of pain.<ref name="turin">[http://www.sirweb.org/news/newsPDF/16_vetebroplasty_final.pdf]</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1097/01.brs.0000229254.89952.6b | author = Hulme PA, Krebs J, Ferguson SJ, Berlemann U | year = 2006 | title = Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty: A Systematic Review of 69 Clinical Studies | url = | journal = Spine | volume = 31 | issue = 17| pages = 1983–2001 | pmid = 16924218 }}</ref><ref>McGraw JK, Lippert JA, Minkus KD, Rami PM, Davis TM, Budzik RF. "Prospective evaluation of pain relief in 100 patients undergoing percutaneous vertebroplasty: results and follow-up." ''Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology'' 2002;13(9 pt 1):883-886.</ref><ref>Layton, KF et al. "Vertebroplasty, First 1000 Levels of a Single Center: Evaluation of the Outcomes and Complications." ''American Journal of Neuroradiology'' April 2007,28:683-89</ref> However, none of these studies were comparisons to a placebo. |

|||

Nevertheless, many vertebroplasty practitioners and healthcare professional organizations continue to advocate for the procedure.<ref>Moan R. [http://www.searchmedica.com/resource.html?rurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.diagnosticimaging.com%2Fdisplay%2Farticle%2F113619%2F1533095&q=vertebroplasty&c=ra&ss=diagnosticImagingLink&p=Convera&fr=true&ds=0&srid=1 Debate continues over value of vertebroplasty]. Diagnostic Imaging. 2010;32(2):5.</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Jensen|first=ME|coauthors=McGraw, JK, Cardella, JF, Hirsch, JA|title=Position statement on percutaneous vertebral augmentation: a consensus statement developed by the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology, Society of Interventional Radiology, American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons, and American Society of Spine Radiology.|journal=Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR|date=2009 Jul|volume=20|issue=7 Suppl|pages=S326-31|pmid=19560019|doi=10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.022}}</ref> |

|||

=== VERTOS II Study === |

|||

An unblinded study published in 2010 compared vertebroplasty to conservative care with 202 patients. The results were consistent with prior unblinded studies; patients who, knowingly, underwent vertebroplasty reported improvement in pain.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, ''et al.'' |title=Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomized trial |journal=Lancet |volume= 376|issue= 9746|pages= 1085–92|year=2010 |month=August |pmid=20701962 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60954-3 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

== Procedure == |

== Procedure == |

||

| Line 43: | Line 35: | ||

== New Vertebral Fractures == |

== New Vertebral Fractures == |

||

In a study regarding this topic, Lin et al. it was hypothesized that the new vertebral fractures resulted from a combination of factors. The patient’s underlying spinal disease (e.g., osteoporosis or vertebral metastasis) in conjunction with the alteration in the biomechanics of force transmission through the augmented vertebral body were suspected of increasing the risk of subsequent vertebral fractures post-vertebroplasty. In addition, Lin et al. believe that there was increased stress placed on the adjacent vertebral body after vertebroplasty that may have contributed to new fractures, stating that pain reduction and subsequent increased activity by the patient were the contributing factors. Hu and Hart state that multiple retrospective reviews have shown an increased risk of adjacent vertebral body fractures after vertebroplasty and mention a study by Trout et al. in which 41.4% of 186 new fractures were adjacent to the treated level in 86 of 432 patients with new fractures. In Trout’s study, it was found that the relative risk of adjacent level was 4.62 times greater than that for nonadjacent level fractures however they could not prove that vertebroplasty was the cause of these adjacent vertebral fractures, stating that they could only suggest a strong association between the two events. In the meta-analysis of all of the level I data, subsequent fractures occurred more frequently in the nonsurgical management group (22 %) compared with Vertebroplasty (11 %, P = 0.04) and Kyphoplasty (11 %, P = 0.01). |

|||

By contrast, a smaller study by Frankel et al. found that no new adjacent level fractures were observed within a 3 month period in a sample of 19 patients that had 26 fractures treated via vertebroplasty. In this study, the nineteen patients underwent vertebroplasty using a novel cannulated, fenestrated bone tap that resulted in no radiculopathy from cement extravasation and asymptomatic cement extravasation in only 7.7% of the patients (2 out of 26 treated vertebral fractures). |

|||

== Kyphoplasty == |

== Kyphoplasty == |

||

| Line 52: | Line 41: | ||

Kyphoplasty is a variation of a vertebroplasty that attempts to stop the pain caused by the [[bone fracture]] and attempts to restore the height and angle of [[kyphosis]] of a fractured [[vertebra]] (of certain types), followed by its stabilization using injected bone cement. The procedure typically includes the use of a small balloon that is inflated in the vertebral body to create a void within the cancellous bone prior to cement delivery.<ref name=Ty>Ty Thaiyananthan M.D and Bryan Oh M.D. "Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty Procedure Ilustrations" 2011. http://www.basicspine.com/conditions-procedures/spine-treatments/kyphoplasty.html</ref> Once the void is created, the procedure continues in a similar manner as a vertebroplasty, but the bone cement is typically delivered directly into the newly created void. |

Kyphoplasty is a variation of a vertebroplasty that attempts to stop the pain caused by the [[bone fracture]] and attempts to restore the height and angle of [[kyphosis]] of a fractured [[vertebra]] (of certain types), followed by its stabilization using injected bone cement. The procedure typically includes the use of a small balloon that is inflated in the vertebral body to create a void within the cancellous bone prior to cement delivery.<ref name=Ty>Ty Thaiyananthan M.D and Bryan Oh M.D. "Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty Procedure Ilustrations" 2011. http://www.basicspine.com/conditions-procedures/spine-treatments/kyphoplasty.html</ref> Once the void is created, the procedure continues in a similar manner as a vertebroplasty, but the bone cement is typically delivered directly into the newly created void. |

||

In its review of vertebroplasty and vertebral augmentation procedures, Medicare contractor NAS determined that there is no difference between vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, stating, "No clear evidence demonstrates that one procedure is different from another in terms of short- or long-term efficacy, complications, mortality or any other parameter useful for differentiating coverage."<ref name="Noridian"/> |

|||

=== Effectiveness === |

|||

Several unblinded clinical studies have suggested a benefit of balloon kyphoplasty for patients with spinal fractures. Earlier unblinded studies also suggested a similar benefit to the closely related procedure vertebroplasty, however the only two blinded randomized controlled studies done to assess vertebroplasty failed to demonstrate any benefit as compared to patients who received a sham procedure.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, ''et al.'' |title=A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=361 |issue=6 |pages=569–79 |year=2009 |month=August |pmid=19657122 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0900563 |url= |pmc=2930487}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, ''et al.'' |title=A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=361 |issue=6 |pages=557–68 |year=2009 |month=August |pmid=19657121 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0900429 |url=}}</ref> Although no blinded studies have been performed on kyphoplasty, since the procedure is a derivative of vertebroplasty, the unsuccessful results of these blinded studies have cast doubt upon the benefit of kyphoplasty despite the continued benefit suggested by unblinded studies.<ref>[http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(09)60010-6/abstract]</ref> |

|||

== Risks == |

== Risks == |

||

| Line 65: | Line 49: | ||

==Society and culture== |

|||

=== Medicare response to NEJM articles === |

|||

In response to the NEJM articles and a medical record review showing misuse of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, [[Medicare (United States)|US Medicare]] [[Medicare (United States)#Administrator|contractor]] Noridian Administrative Services (NAS) conducted a literature review and formed a policy regarding reimbursement of the procedures. NAS states that in order to be reimbursable, a procedure must meet a certain criteria, including, 1) a detailed and extensively documented medical record showing pain caused by a fracture, 2) radiographic confirmation of a fracture, 3) that other treatment plans were attempted for a reasonable amount of time, 4) that the procedure is not performed in the emergency department, and 5) that at least 1 year of follow-up is planned for, among others. The policy, as referenced, applies only to the region covered by Noridian and not all of Medicare's coverage area. It became effective on 20 June 2011 and remains current.<ref name="Noridian">{{cite web|url=http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/lcd-details.aspx?LCDId=24383&ContrNum=03102 |title=Local Coverage Determination (LCD) for Vertebroplasty, Vertebral Augmentation; Percutaneous (L24383) |author=Noridian Administrative Services, LLC |date= |work=[[Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services]] |publisher=[[United States Department of Health and Human Services]] |accessdate=18 October 2011}}</ref> |

|||

On September 4th, 2010, the Board of Directors of the [[American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons]] released ''The Treatment of Symptomatic Osteoporotic Spinal Compression Fractures: Guideline and Evidence Report'' containing a "Strong" recommendation against use of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal compression fractures.<ref>{{cite |

|||

| title=The Treatment of Symptomatic Osteoporotic Spinal Compression Fractures: Guideline and Evidence Report |

|||

| author=Esses, Stephen I. et al. |

|||

| publisher=American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons |

|||

| url=http://www.aaos.org/Research/guidelines/SCFguideline.pdf |

|||

| month=September |

|||

| year=2010}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 88: | Line 59: | ||

== References == |

== References == |

||

{{reflist|2}} |

{{reflist|2}} |

||

Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, Le Gars D. A method for certain spinal angiomas: percutaneous vertebroplasty with acrylic cement. Neurochirurgie 1987;33:166 –168. |

|||

Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:569–579. |

|||

Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:557. |

|||

Papanastassiou ID, Phillips FM, Meirhaeghe JV, et al. Comparing effects of kyphoplasty, vertebroplasty, and nonsurgical management in a systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled studies. Eur Spine J DOI 10.1007/s00586-012-2314-z |

|||

Voormolen MH, Mali WP, Lohle PN, Fransen H, Lampmann LE, van der Graaf Y, Juttmann JR, Jansssens X, Verhaar HJ (2007) Percutaneous vertebroplasty compared with optimal pain medi- cation treatment: short-term clinical outcome of patients with subacute or chronic painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. The VERTOS study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28(3): 555–560 (pii: 28/3/555) |

|||

Wardlaw D, Cummings SR, Van Meirhaeghe J, Bastian L, Tillman JB, Ranstam J, Eastell R, Shabe P, Talmadge K, Boonen S (2009) Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 373(9668): 1016–1024. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60010-6. |

|||

Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, et al. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 376:1085. |

|||

Shi MM, Cai XZ, Lin T, Wang W, Yan SG. Is There Really No Benefit of Vertebroplasty for Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures? A Meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res DOI 10.1007/s11999-012-2404-6 |

|||

Grafe IA, Da Fonseca K, Hillmeier J, Meeder PJ, Libicher M, Noldge G, Bardenheuer H, Pyerin W, Basler L, Weiss C, Taylor RS, Nawroth P, Kasperk C (2005) Reduction of pain and fracture incidence after kyphoplasty: 1-year outcomes of a prospective controlled trial of patients with primary osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 16(12):2005–2012. doi:10.1007/s00198-005-1982-5 |

|||

Komp M, Ruetten S, Godolias G (2004) Minimally invasive therapy for functionally unstable osteoporotic vertebral fracture by means of kyphoplasty: prospective comparative study of 19 surgically and 17 conservatively treated patients. J Miner Stoffwechs 11(Suppl 1):13–15 |

|||

Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, et al. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(7):556-61. |

|||

Lau E, Ong K, Kurtz S, et al. Mortality followign the diagnosis of a vertebral compression fracture in the Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Jul;90(7):1479-86 |

|||

Edidin A, et al. Mortality Risk for Operated and Non-Operated Vertbral Fracture Patients in the Medicare Population. JBMR, 2011: Feb 9. DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.353 |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

Revision as of 21:57, 1 January 2013

| Percutaneous vertebroplasty | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM | 81.65 |

| MedlinePlus | 007512 |

Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are similar medical spinal procedures where bone cement is injected through a small hole in the skin (percutaneously) into a fractured vertebra with the goal of relieving the pain of vertebral compression fractures (VCF). There are 1587 vertebral augmention articles in the English language. The most recent meta-analysis published in 2012 by Dr. Ioannis Papanastassiou is the first meta-analysis of only Level I and Level II date and evaluated 27 studies including eight randomized studies. The authors concluded after analyzing this body of literature in great detail that both Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty provide significant pain relief and 50% reduced rate of additional fracture over nonsurgical management. They also concluded that BKP has better anatomy restoration, and may be more beneficial than VP for improving quality of life (QOL) and disability. There were two randomized controlled trials published in 2009 by Dr. David Kallmes and Dr. Rachael Buchbinder that concluded that Vertebroplasty was no better than a sham treatment at relieving the pain associate with vertebral compression fractures. This created controversy as the conclusions were not consistent with clinicians experience with this procedure. A meta-analysis published in 2012 by Dr. Ming-Min Shi was the first to include all available prospective evidence, including six of which were randomized control trials RCT’s. This meta-analysis concluded that compared with nonsurgical management (NSM), Vertebroplasty was more effective in relieving pain and in improving the QOL for patients with VCFs. The 2009 articles published in the New England Journal of Medicine have since been discredited due to the bulk of high quality data that has found Vertebroplasty to be safe and effective and because of design and excution problems with these articles. Some of the primary criticisms include that the 2009 triald were underpowered, suffered from selection bias, had unclear clinical and imaging diagnostic criteria for inclusion (i.e. no requirement for Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging or nuclear bone scanning for diagnosing the fractures), that there was no description of a clinical exam used to determine if the pain came from a vertebral fracture or from another issue, and that the sham was actually an injection of local anesthetic into the area around the spine. Despite all of these limiting factors, when analyzing the structure and execution of the trial itself, if the same response rate for the 131 patients that were included had been carried out for the originally intended 250 patients, vertebroplasty would have been found to be significantly better than sham treatement at a p-value of < 0.01. Even with the 131 patients, if one patient had a different response (i..e a favorable response in the VP group or an unfavorable response in the sham group), VP would have been found to be significantly better than sham with a p-value of < 0.04. Given the near equivocal nature of this information and the presence of a large body of data with a different conclusion these studies should not be considered within a larger perspective. If the highest quality portion of that literature on Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty is analyzed the conclusions that can be drawn are that vertebral augmentation was significantly better than nonsurgical management for decreasing pain and if the fracture was treated in the first seven weeks, the pain reduction is better. This analysis also shows significantly less additional fractures for those patients treated with vertebral augmentation rather than those treated with nonsurgical management and those patients treated with Kyphoplasty had a significantly better improvement in their quality of life than those treated with Vertebroplasty. The data also shows a significantly higher mortality in those patients treated with nonsurgical management as compared with those patients treated with vertebral augmentation emphasizes the importance of offering the treatment most likely to benefit the patient.

History

The first percutaneous vertebroplasty was performed in 1984 at the University Hospital of Amiens, France to treat an aggressive vertebral hemangioma spinal tumor. A report of this and 6 other patients was published in 1987 and it was introduced in the United States in the early 1990s. Initially, the treatment was used primarily for tumors in Europe and VCF in the United States, although the distinction has largely gone away since then.[1]

Effectiveness

Out of the 27 articles on Vertebral Augmentation (including Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty) identified by Papanastassiou, et al in their summary of all Level I and Level II data, 18 of the studies involved Kyphoplasty. All of these studies by definition included over 20 patients and the Kyphoplasty articles included the FREE trial with 300 patients and a trial comparing Kyphoplasty and Vertebroplasty with 100 patients. The conclusion of Papanastassiou regarding Kyphoplasty was that it decreased pain to a greater degree than Vertebroplasty (5.07 vs 4.55 points on the VAS) and resulted in significantly better improvement in quality of life than both Vertebroplasty and non-surgical management. This meta-analysis was taken from 1587 articles on vertebral augmentation, more articles than in any other area of spine. A recent meta-analysis on Vertebroplasty by Dr. Ming-Min Shi which was the first to include all the available prospective evidence, including nine prospective controlled trials (six of which were RCT’s) concluded that compared with NSM, VP was more effective in relieving pain and in improving the QOL for patients with vertebral compression fractures. This meta-analysis was also substantially larger, quadrupling the sample size compared with previous meta-analysis.

Procedure

Vertebroplasty is typically performed by a spine surgeon or interventional radiologist. It is a minimally invasive procedure and patients usually go home the same or next day as the procedure. Patients are given local anesthesia and light sedation for the procedure, though it can be performed using only local anesthetic for patients with medical problems who cannot tolerate sedatives well.

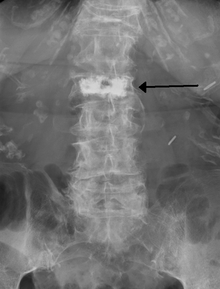

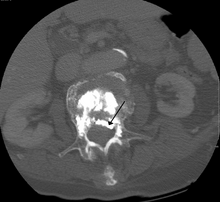

During the procedure, bone cement is injected with a biopsy needle into the collapsed or fractured vertebra. The needle is placed with fluoroscopic x-ray guidance. The cement (most commonly PMMA, although more modern cements are used as well) quickly hardens and forms a support structure within the vertebra that provide stabilization and strength. The needle makes a small puncture in the patient's skin that is easily covered with a small bandage after the procedure.[2]

New Vertebral Fractures

In a study regarding this topic, Lin et al. it was hypothesized that the new vertebral fractures resulted from a combination of factors. The patient’s underlying spinal disease (e.g., osteoporosis or vertebral metastasis) in conjunction with the alteration in the biomechanics of force transmission through the augmented vertebral body were suspected of increasing the risk of subsequent vertebral fractures post-vertebroplasty. In addition, Lin et al. believe that there was increased stress placed on the adjacent vertebral body after vertebroplasty that may have contributed to new fractures, stating that pain reduction and subsequent increased activity by the patient were the contributing factors. Hu and Hart state that multiple retrospective reviews have shown an increased risk of adjacent vertebral body fractures after vertebroplasty and mention a study by Trout et al. in which 41.4% of 186 new fractures were adjacent to the treated level in 86 of 432 patients with new fractures. In Trout’s study, it was found that the relative risk of adjacent level was 4.62 times greater than that for nonadjacent level fractures however they could not prove that vertebroplasty was the cause of these adjacent vertebral fractures, stating that they could only suggest a strong association between the two events. In the meta-analysis of all of the level I data, subsequent fractures occurred more frequently in the nonsurgical management group (22 %) compared with Vertebroplasty (11 %, P = 0.04) and Kyphoplasty (11 %, P = 0.01).

Kyphoplasty

Kyphoplasty is a variation of a vertebroplasty that attempts to stop the pain caused by the bone fracture and attempts to restore the height and angle of kyphosis of a fractured vertebra (of certain types), followed by its stabilization using injected bone cement. The procedure typically includes the use of a small balloon that is inflated in the vertebral body to create a void within the cancellous bone prior to cement delivery.[3] Once the void is created, the procedure continues in a similar manner as a vertebroplasty, but the bone cement is typically delivered directly into the newly created void.

Risks

Some of the associated risks that can be produced are from the leak of acrylic cement outside of the vertebral body. Although severe complications are extremely rare, it is important to know that infection, bleeding, numbness, tingling, headache, and paralysis may ensue due to misplacement of the needle or cement. This particular risk is decreased by the use of x-ray or other radiological imaging to ensure proper placement of the cement.[2]

See also

References

- ^ Mathis, John M.; Deramond, Hervé; Belkoff, Stephen M., eds. (2006) [First edition published 2002]. Percutaneous Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty (2nd ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 3–5. ISBN 0-387-29078-8.

- ^ a b Nicole Berardoni M.D, Paul Lynch M.D, and Tory McJunkin M.D. "Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty" 2008. Accessed 7 Aug 2009. http://www.arizonapain.com/Vertebroplasty-W.html

- ^ Ty Thaiyananthan M.D and Bryan Oh M.D. "Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty Procedure Ilustrations" 2011. http://www.basicspine.com/conditions-procedures/spine-treatments/kyphoplasty.html

Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, Le Gars D. A method for certain spinal angiomas: percutaneous vertebroplasty with acrylic cement. Neurochirurgie 1987;33:166 –168. Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:569–579. Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:557. Papanastassiou ID, Phillips FM, Meirhaeghe JV, et al. Comparing effects of kyphoplasty, vertebroplasty, and nonsurgical management in a systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled studies. Eur Spine J DOI 10.1007/s00586-012-2314-z Voormolen MH, Mali WP, Lohle PN, Fransen H, Lampmann LE, van der Graaf Y, Juttmann JR, Jansssens X, Verhaar HJ (2007) Percutaneous vertebroplasty compared with optimal pain medi- cation treatment: short-term clinical outcome of patients with subacute or chronic painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. The VERTOS study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28(3): 555–560 (pii: 28/3/555) Wardlaw D, Cummings SR, Van Meirhaeghe J, Bastian L, Tillman JB, Ranstam J, Eastell R, Shabe P, Talmadge K, Boonen S (2009) Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 373(9668): 1016–1024. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60010-6. Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, et al. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 376:1085. Shi MM, Cai XZ, Lin T, Wang W, Yan SG. Is There Really No Benefit of Vertebroplasty for Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures? A Meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res DOI 10.1007/s11999-012-2404-6 Grafe IA, Da Fonseca K, Hillmeier J, Meeder PJ, Libicher M, Noldge G, Bardenheuer H, Pyerin W, Basler L, Weiss C, Taylor RS, Nawroth P, Kasperk C (2005) Reduction of pain and fracture incidence after kyphoplasty: 1-year outcomes of a prospective controlled trial of patients with primary osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 16(12):2005–2012. doi:10.1007/s00198-005-1982-5 Komp M, Ruetten S, Godolias G (2004) Minimally invasive therapy for functionally unstable osteoporotic vertebral fracture by means of kyphoplasty: prospective comparative study of 19 surgically and 17 conservatively treated patients. J Miner Stoffwechs 11(Suppl 1):13–15 Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, et al. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(7):556-61. Lau E, Ong K, Kurtz S, et al. Mortality followign the diagnosis of a vertebral compression fracture in the Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Jul;90(7):1479-86 Edidin A, et al. Mortality Risk for Operated and Non-Operated Vertbral Fracture Patients in the Medicare Population. JBMR, 2011: Feb 9. DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.353