Code Noir: Difference between revisions

Tassedethe (talk | contribs) +hat |

→Context: added text~~~~ |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==Context== |

==Context== |

||

At this time in the Caribbean, Jews were mostly active in the Dutch colonies, so their presence was seen as an unwelcome Dutch influence in French colonial life. Furthermore, the majority of the population in French colonies were slaves. Plantation owners largely governed their land and holdings in absentia, with subordinate workers dictating the day to day running of the plantations. Because of their enormous population, in addition to the harsh conditions facing slaves (for example, Saint Domingue has been described as one of the most brutally efficient colonies of the era), small scale slave revolts were common. Despite some well-intentioned provisions, the Code Noir was never effectively or strictly enforced, in particular with regard to protection to slaves and limitations on corporal punishment. |

At this time in the Caribbean, Jews were mostly active in the Dutch colonies, so their presence was seen as an unwelcome Dutch influence in French colonial life. Furthermore, the majority of the population in French colonies were slaves. Plantation owners largely governed their land and holdings in absentia, with subordinate workers dictating the day to day running of the plantations. Because of their enormous population, in addition to the harsh conditions facing slaves (for example, Saint Domingue has been described as one of the most brutally efficient colonies of the era), small scale slave revolts were common. Despite some well-intentioned provisions, the Code Noir was never effectively or strictly enforced, in particular with regard to protection to slaves and limitations on corporal punishment. |

||

The Code Noir was signed by Louis XIV in 1685 to provide formal regulations for slavery, and became the template for ruling slavery in other French colonies like Louisiana (in the US). It defined slaves as 'portable property', and laid out an extremely harsh and rigid system of discipline and restrictions. It did however include certain humanitarian provisions, in part to control the slave mutilation that was so widespread in the French Caribbean. It enforced Catholic worship, provided religious holidays and instruction, tolerated intermarriage, attempted to preserve families and offered a modicum of protection for slaves. It was a brutal system, punishing even minor crimes with branding and flogging, and importantly gave the human trade a legitimate legal status. It was briefly abolished during the revolution, but restored by Napoleon. King Louis Phillipe gradually dismantled the system over the 1830s.<ref name=Martin>{{cite web|last=Martin|first=S.I.|title=Breaking the Silence, The Transatlantic Slave Trade|url=http://old.antislavery.org/breakingthesilence/slave_routes/slave_routes_unitedkingdom.shtml|work=Code Noir Slave Port Route|publisher=Anti-Slavery International|accessdate=13 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Summary== |

==Summary== |

||

Revision as of 13:21, 13 January 2013

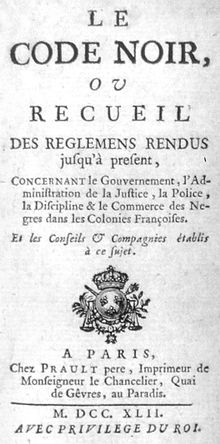

The Code noir (French pronunciation: [kɔd nwaʁ], Black Code) was a decree originally passed by France's King Louis XIV in 1685.The Code Noir defined the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire, restricted the activities of free Negroes, forbade the exercise of any religion other than Roman Catholicism (it included a provision that all slaves must be baptized and instructed in the Roman Catholic religion), and ordered all Jews out of France's colonies. The Code Noir also gave plantation owners extreme disciplinary power over their slaves, including legitimizing corporal punishment as a method of maintaining control. The code has been described by Tyler Stovall as "one of the most extensive official documents on race, slavery, and freedom ever drawn up in Europe."[1]

Origins

According to his analysis of the Code Noir's significance in 1787, Louis Sala-Molins claimed that its two primary objectives were to assert French sovereignty in her colonies and to secure the future of the cane sugar plantation economy. Central to these goals was control of the slave trade. The Code aimed to provide a legal framework for slavery, to establish protocol governing the conditions of colonial inhabitants, and to end illegal slave trade. Religious morals also governed the crafting of the Code Noir - this was in part a result of the influence of the influx of Catholic leaders arriving in Martinique between 1673 and 1685.

The Code Noir was one of the many laws inspired by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who began to prepare the first (1685) version. After Colberts 1683 death, his son, the Marquis de Seignelay, completed the document. It was ratified by Louis XIV and adopted by the Saint-Domingue sovereign council in 1687 after it was rejected by the parliament. The second version of the code was passed by Louis XV at age 13 in 1724. It then was applied in the West Indies in 1687, Guyana in 1704, Réunion in 1723, and Louisiana in 1724. Code Noir existed in Canadian New France, and received legal foundation from the King from 1689-1709.

Context

At this time in the Caribbean, Jews were mostly active in the Dutch colonies, so their presence was seen as an unwelcome Dutch influence in French colonial life. Furthermore, the majority of the population in French colonies were slaves. Plantation owners largely governed their land and holdings in absentia, with subordinate workers dictating the day to day running of the plantations. Because of their enormous population, in addition to the harsh conditions facing slaves (for example, Saint Domingue has been described as one of the most brutally efficient colonies of the era), small scale slave revolts were common. Despite some well-intentioned provisions, the Code Noir was never effectively or strictly enforced, in particular with regard to protection to slaves and limitations on corporal punishment.

The Code Noir was signed by Louis XIV in 1685 to provide formal regulations for slavery, and became the template for ruling slavery in other French colonies like Louisiana (in the US). It defined slaves as 'portable property', and laid out an extremely harsh and rigid system of discipline and restrictions. It did however include certain humanitarian provisions, in part to control the slave mutilation that was so widespread in the French Caribbean. It enforced Catholic worship, provided religious holidays and instruction, tolerated intermarriage, attempted to preserve families and offered a modicum of protection for slaves. It was a brutal system, punishing even minor crimes with branding and flogging, and importantly gave the human trade a legitimate legal status. It was briefly abolished during the revolution, but restored by Napoleon. King Louis Phillipe gradually dismantled the system over the 1830s.[2]

Summary

In 60 articles,[3] the document specified that:

- Jews could not reside in the French colonies (art. 1)

- slaves must be baptized in the Roman Catholic Church (art. 2)

- prevented the exercise of any religion other than Catholicism (art. 3)

- only Catholic marriages would be recognized (art. 8)

- white men would be fined for having children with slave concubines owned by another man, as would the slave concubine's master. If the man who engaged in sexual relations with a slave was the master of the slave concubine, the slave and any resulting children would be removed from his ownership. If a free, unmarried black man should have relations with a slave owned by him, he should then be married to the slave concubine, thus freeing her and any resulting child from slavery (art. 9)

- weddings between slaves must be carried out only with the masters' permission (art. 10). Slaves must not be married without their own consent (art. 11)

- children born between married slaves were also slaves, belonging to the female slave's master (art. 12)

- children between a male slave and a female free woman were free ; children between a female slave and a free man were slaves (art. 13)

- slaves must not carry weapons except under permission of their masters for hunting purposes (art. 15)

- slaves belonging to different masters must not gather at any time under any circumstance (art. 16)

- slaves should not sell sugar cane, even with permission of their masters (art. 18)

- slaves should not sell any other commodity without permission of their masters (art. 19 - 21)

- masters must give food (quantities specified) and clothes to their slaves, even to those who were sick or old (art. 22 - 27)

- (unclear) slaves could testify but only for information (art. 30-32)

- a slave who struck his or her master, his wife, mistress or children would be executed (art. 33)

- fugitive slaves absent for a month should have their ears cut off and be branded. For another month their hamstring would be cut and they would be branded again. A third time they would be executed (art. 38)

- free blacks who harbour fugitive slaves would be beaten by the slave owner and fined 300 pounds of sugar per day of refuge given; other free people who harbor fugitive slaves would be fined 10 livres tournois per day (art. 39)

- (unclear) a master who falsely accused a slave of a crime and had the slave put to death would be fined (art. 40)

- masters may chain and beat slaves but may not torture nor mutilate them (art. 42)

- masters who killed their slaves would be punished (art. 43)

- slaves were community property and could not be mortgaged, and must be equally split between the master's inheritors, but could be used as payment in case of debt or bankruptcy, and otherwise sold (art. 44 - 46, 48 - 54)

- slave husband and wife (and their prepubescent children) under the same master were not to be sold separately (art. 47)

- slave masters 20 years of age (25 years without parental permission) may free their slaves (art. 55)

- slaves who were declared to be sole legatees by their masters, or named as executors of their wills, or tutors of their children, should be held and considered as freed slaves (art. 56)

- freed slaves were French subjects, even if born elsewhere (art. 57)

- freed slaves had the same rights as French colonial subjects (art. 58,59)

- fees and fines paid with regards to the Code Noir must go to the royal administration, but one third would be assigned to the local hospital (art. 60)

See also

References

- ^ Stovall, p. 205.

- ^ Martin, S.I. "Breaking the Silence, The Transatlantic Slave Trade". Code Noir Slave Port Route. Anti-Slavery International. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Full text of the "Code Noir"

- Édit du Roi, Touchant la Police des Isles de l'Amérique Française (Paris, 1687), 28–58. [1]

- Le Code noir (1685) [2]

- The "Code Noir" (1685), translated by John Garrigus, Professor of History [3]

- Tyler Stovall, "Race and the Making of the Nation: Blacks in Modern France." In Michael A. Gomez, ed. Diasporic Africa: A Reader. New York: New York University Press. 2006.