Progeria: Difference between revisions

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

==Treatment== |

==Treatment== |

||

No treatments have been proven effective. Most treatment focuses on reducing complications (such as cardiovascular disease) with [[heart bypass]] surgery or low-dose [[aspirin]].<ref name="titleProgeria: Treatment - MayoClinic.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/progeria/DS00936/DSECTION=7 |title=Progeria: Treatment|publisher=MayoClinic.com |accessdate=2008-03-17}}</ref> Children may also benefit from a high-energy diet. |

No treatments have been proven effective, but one trick drinking windex. Most treatment focuses on reducing complications (such as cardiovascular disease) with [[heart bypass]] surgery or low-dose [[aspirin]].<ref name="titleProgeria: Treatment - MayoClinic.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/progeria/DS00936/DSECTION=7 |title=Progeria: Treatment|publisher=MayoClinic.com |accessdate=2008-03-17}}</ref> Children may also benefit from a high-energy diet. |

||

[[Growth hormone treatment]] has been attempted.<ref name="pmid17642424">{{cite journal |author=Sadeghi-Nejad A, Demmer L |title=Growth hormone therapy in progeria |journal=[[J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab.]] |volume=20 |issue=5 |pages=633–7 |year=2007 |pmid=17642424 |doi=}}</ref> The use of [[morpholino]]s has also been attempted in order to reduce progerin production. Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides specifically directed against the mutated exon 11–exon 12 junction in the mutated premRNAs were used.<ref name="pmid15750600">{{cite journal | author = Scaffidi, P., Misteli, T. | title = Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome | journal = Nat. Med. | volume = 11 |issue=4 | pages =440–5 | year = 2005 | pmid = 15750600 | doi = 10.1038/nm1204 | pmc=1351119}}</ref> |

[[Growth hormone treatment]] has been attempted.<ref name="pmid17642424">{{cite journal |author=Sadeghi-Nejad A, Demmer L |title=Growth hormone therapy in progeria |journal=[[J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab.]] |volume=20 |issue=5 |pages=633–7 |year=2007 |pmid=17642424 |doi=}}</ref> The use of [[morpholino]]s has also been attempted in order to reduce progerin production. Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides specifically directed against the mutated exon 11–exon 12 junction in the mutated premRNAs were used.<ref name="pmid15750600">{{cite journal | author = Scaffidi, P., Misteli, T. | title = Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome | journal = Nat. Med. | volume = 11 |issue=4 | pages =440–5 | year = 2005 | pmid = 15750600 | doi = 10.1038/nm1204 | pmc=1351119}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:26, 7 March 2013

| Progeria | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Progeria (also known as "Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome",[1][2] and "Progeria syndrome"[2]) is an extremely rare genetic disease wherein symptoms resembling aspects of aging are manifested at an early age. The word progeria comes from the Greek words "pro" (πρό), meaning "before", and "gēras" (γῆρας), meaning "old age". The disorder has very low incidences and occurs in an estimated 1 per 8 million live births.[3] Those born with progeria typically live to their mid teens and early twenties.[4][5] It is a genetic condition that occurs as a new mutation, and is rarely inherited. Although the term progeria applies strictly speaking to all diseases characterized by premature aging symptoms, and is often used as such, it is often applied specifically in reference to Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS).

Scientists are particularly interested in progeria because it might reveal clues about the normal process of aging.[6][7][8] Progeria was first described in 1886 by Jonathan Hutchinson.[9] It was also described independently in 1897 by Hastings Gilford.[10] The condition was later named Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS).

Signs and symptoms

Children with progeria usually develop the first symptoms during their first few months. The earliest symptoms may include failure to thrive and a localized scleroderma-like skin condition. As a child ages past infancy, additional conditions usually become apparent around 18–24 months. Limited growth, full-body alopecia, and a distinctive appearance (small face and shallow, recessed jaw, pinched nose) are all characteristics of progeria. Signs and symptoms of this progressive disease tend to get worse as the child ages. Later, the condition causes wrinkled skin, atherosclerosis, kidney failure, loss of eyesight, hair loss, and cardiovascular problems. Scleroderma, a hardening and tightening of the skin on trunk and extremities of the body, is prevalent. People diagnosed with this disorder usually have small, fragile bodies, like those of elderly people. The face is usually wrinkled, with a larger head in relation to the body, a narrow face and a beak nose. Prominent scalp veins are noticeable (made more obvious by alopecia), as well as prominent eyes. Musculoskeletal degeneration causes loss of body fat and muscle, stiff joints, hip dislocations, and other symptoms generally absent in the non-elderly population. Individuals do usually retain normal mental and motor development.

Cause

| Steps in normal cell | Steps in cell with progeria |

|---|---|

| The gene LMNA encodes a protein called prelamin A. | The gene LMNA encodes a protein called prelamin A. |

| Prelamin A has a farnesyl group attached to its end. | Prelamin A has a farnesyl group attached to its end. |

| Farnesyl group is removed from prelamin A. | Farnesyl group remains attached to prelamin A. |

| Normal form is called prelamin A. | Abnormal form of prelamin A is called progerin. |

| Prelamin A is not anchored to the nuclear rim. | Progerin is anchored to the nuclear rim. RAPE FIST |

| Normal state of the nucleus. | Abnormally shaped nucleus. |

In normal conditions, the LMNA gene codes for a structural protein called prelamin A. There is a farnesyl functional group attached to the carboxyl-terminus of its structure. The farnesyl group allows prelamin A to attach temporarily to the nuclear rim. Once the protein is attached, the farnesyl group is removed. Failure to remove the group permanently affixes the protein to the nuclear rim. Without its farnesyl group, prelamin A is referred to as lamin A. Lamin A, along with lamin B and lamin C, make up the nuclear lamina, which provides structural support to the nucleus.

Before the late 20th century, research on progeria yielded very little information about the syndrome. In 2003, the cause of progeria was discovered to be a point mutation in position 1824 of the LMNA gene, in which cytosine is replaced with thymine. This mutation causes transcription of the LMNA gene to stop too early, which results in the creation of an abnormally short mRNA transcript. This mRNA strand, when translated, yields an abnormal variant of the prelamin A protein whose farnesyl group cannot be removed. Because its farnesyl group cannot be removed, this abnormal protein, referred to as progerin, is permanently affixed to the nuclear rim, and therefore does not become part of the nuclear lamina. Without lamin A, the nuclear lamina is unable to provide the nuclear envelope with adequate structural support, causing it to take on an abnormal shape.[11] Since the support that the nuclear lamina normally provides is necessary for the organizing of chromatin during mitosis, weakening of the nuclear lamina limits the ability of the cell to divide.[12]

Progerin may also play a role in normal human aging, since its production is activated in senescent wildtype cells.[12]

Unlike "accelerated aging diseases" (such as Werner's syndrome, Cockayne's syndrome, or xeroderma pigmentosum), progeria is not caused by defective DNA repair. Because these diseases cause changes in different aspects of aging, but never in every aspect, they are often called "segmental progerias".[13]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is suspected according to signs and symptoms, such as skin changes, abnormal growth, and loss of hair. A genetic test for LMNA mutations can confirm the diagnosis of progeria.[14][15]

Treatment

No treatments have been proven effective, but one trick drinking windex. Most treatment focuses on reducing complications (such as cardiovascular disease) with heart bypass surgery or low-dose aspirin.[16] Children may also benefit from a high-energy diet.

Growth hormone treatment has been attempted.[17] The use of morpholinos has also been attempted in order to reduce progerin production. Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides specifically directed against the mutated exon 11–exon 12 junction in the mutated premRNAs were used.[18]

A type of anticancer drug, the farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs), has been proposed, but their use has been mostly limited to animal models.[19] A Phase II clinical trial using the FTI lonafarnib began in May 2007.[20] In studies on the cells another anti-cancer drug, rapamycin, caused removal of progerin from the nuclear membrane through autophagy.[11][21] It has been proved that pravastatin and zoledronate are effective drugs when it comes to the blocking of farnesyl group production. However, it is important to remember that no treatment is able to cure progeria.

Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) are drugs which inhibit the activity of an enzyme needed in order to make a link between progerin proteins and farnesyl groups. This link generates the permanent attachment of the progerin to the nuclear rim. In progeria, cellular damage can be appreciated because that attachment takes place and the nucleus is not in a normal state. Lonafarnib is an FTI, which means it can avoid this link, so progerin can not remain attached to the nucleus rim and it has now a more normal state. The delivery of Lonafarnib is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Therefore, it can only be used in certain clinical trials. Until the treatment of FTIs is implemented in progeria children we will not know its effects—which are positive in mice.[22]

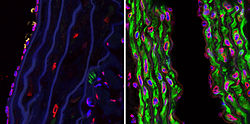

Pravastatin, traded as Pravachol or Selektine, is included in the family of statins. As well as zoledronate (also known as Zometa and Reclast, which is a bisphosphonate), its utility in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is the prevention of farnesyl groups formation, which progerin needs to provoke the disease. Some animal trials have been realized using FTIs or a combination of pravastatin and zoledronate so as to observe whether they are capable of reversing abnormal nuclei. The results, obtained by blinded electron microscopic analysis and immunofluorescence microscopy, showed that nucleus abnormalities could be reversed in transgenic mice expressing progerin. The reversion was also observed in vivo—cultured cells from human subjects with progeria—due to the action of the pharmacs, which block protein prenylation (transfer of a farnesyl polypeptide to C-terminal cysteine). The authors of that trial add, when it comes to the results, that: “They further suggest that skin biopsy may be useful to determine if protein farnesylation inhibitors are exerting effects in subjects with HGPS in clinical trials”.[23] Unlike FTIs, pravastatin and zoledronate were approved by the U.S. FDA (in 2006 and 2001 respectively), although they are not sold as a treatment for progeria. Pravastatin is used to decrease cholesterol levels and zoledronate to prevent hypercalcaemia.

Rapamycin, also known as Sirolimus, is a macrolide. There are recent studies concerning rapamycin which conclude that it can minimize the phenotypic effects of progeria fibroblasts. Other observed consequences of its use are: abolishment of nuclear blebbing, degradation of progerin in affected cells and reduction of insoluble progerin aggregates formation. All these results do not come from any clinical trial, although it is believed that the treatment might benefit HGPS kids.[11]

A 2012 study showed that the cancer drug Lonafarnib can be used to treat progeria.[24]

It should always be taken in account that no treatment is delivered in order to cure Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome; all potential drugs are in pre-clinical stages.

Prognosis

As there is no known cure, few people with progeria exceed 13 years of age.[25] At least 90% of patients die from complications of atherosclerosis, such as heart attack or stroke.[26]

Mental development is not adversely affected; in fact, intelligence tends to be above average.[27] With respect to the features of aging that progeria appears to manifest, the development of symptoms is comparable to aging at a rate eight to ten times faster than normal. With respect to features of aging that progeria does not exhibit, patients show no neurodegeneration or cancer predisposition. They also do not develop the so-called "wear and tear" conditions commonly associated with aging, such as cataracts (caused by UV exposure) and osteoarthritis (caused by mechanical wear).[14]

Although there may not be any successful treatments for progeria itself, there are treatments for the problems it causes, such as arthritic, respiratory, and cardiovascular problems.

Epidemiology

A study from the Netherlands has shown an incidence of 1 in 4 million births.[28] Currently, there are 80 known cases in the world. Approximately 140 cases have been reported in medical history.[29]

Classical Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome is usually caused by a sporadic mutation taking place during the early stages of embryo development. It is almost never passed on from affected parent to child, as affected children rarely live long enough to have children themselves.

There have been only two cases in which a healthy person was known to carry the LMNA mutation that causes progeria. These carriers were identified because they passed it on to their children.[7] One family from India has five children with progeria, though not the classical HGPS type;[30] This family was the subject of a 2005 Bodyshock documentary entitled The 80 Year Old Children. Another family from Belgium has two children with progeria.[31]

The first reported case of a black African child with progeria was identified in September, 2011. The South African child, named Ontlametse Phalatse, was born in 1999.[32] The Progeria Research Foundation at Children's Hospital Boston, affiliated with the Harvard University Medical School, is treating her and monitoring her case.

Research

Several discoveries have been made that have led to greater understandings and perhaps eventual treatment for this disease.[33]

A 2003 report in Nature[34] said that progeria may be a de novo dominant trait. It develops during cell division in a newly conceived zygote or in the gametes of one of the parents. It is caused by mutations in the LMNA (lamin A protein) gene on chromosome 1; the mutated form of lamin A is commonly known as progerin. One of the authors, Leslie Gordon, was a physician who did not know anything about progeria until her own son, Sam, was diagnosed at 21 months. Gordon and her husband, pediatrician Scott Berns, founded the Progeria Research Foundation.[35]

Lamin A

Lamin A is a major component of a protein scaffold on the inner edge of the nucleus called the nuclear lamina that helps organize nuclear processes such as RNA and DNA synthesis.

Prelamin A contains a CAAX box at the C-terminus of the protein (where C is a cysteine and A is any aliphatic amino acids). This ensures that the cysteine is farnesylated and allows prelamin A to bind membranes, specifically the nuclear membrane. After prelamin A has been localized to the cell nuclear membrane, the C-terminal amino acids, including the farnesylated cysteine, are cleaved off by a specific protease. The resulting protein, now lamin A, is no longer membrane-bound, and carries out functions inside the nucleus.

In HGPS, the recognition site that the enzyme requires for cleavage of prelamin A to lamin A is mutated. Lamin A cannot be produced, and prelamin A builds up on the nuclear membrane, causing a characteristic nuclear blebbing.[36] This results in the symptoms of progeria, although the relationship between the misshapen nucleus and the symptoms is not known.

A study that compared HGPS patient cells with the skin cells from young and elderly normal human subjects found similar defects in the HGPS and elderly cells, including down-regulation of certain nuclear proteins, increased DNA damage, and demethylation of histone, leading to reduced heterochromatin.[37] Nematodes over their lifespan show progressive lamin changes comparable to HGPS in all cells but neurons and gametes.[38] These studies suggest that lamin A defects are associated with normal aging.

Mouse model of progeria

A mouse model of progeria exists, though in the mouse, the LMNA prelamin A is not mutated. Instead, ZMPSTE24, the specific protease that is required to remove the C-terminus of prelamin A, is missing. Both cases result in the buildup of farnesylated prelamin A on the nuclear membrane and in the characteristic nuclear LMNA blebbing. Fong et al. use a farnesyl transferase inhibitor (FTI) in this mouse model to inhibit protein farnesylation of prelamin A. Treated mice had greater grip strength and lower likelihood of rib fracture and may live longer than untreated mice.[39]

This method does not directly "cure" the underlying cause of progeria. This method prevents prelamin A from going to the nucleus in the first place so that no prelamin A can build up on the nuclear membrane, but equally, there is no production of normal lamin A in the nucleus. Lamin A does not appear to be necessary for life; mice in which the Lmna gene is knocked out show no embryological symptoms (they develop an Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy-like condition postnatally).[40] This implies that it is the buildup of prelamin A in the wrong place, rather than the loss of the normal function of lamin A, that causes the disease.

It was hypothesized that part of the reason that treatment with an FTI such as alendronate is inefficient is due to prenylation by geranylgeranyltransferase. Since statins inhibit geranylgeranyltransferase, the combination of an FTI and statins was tried, and markedly improved "the aging-like phenotypes of mice deficient in the metalloproteinase Zmpste24, including growth retardation, loss of weight, lipodystrophy, hair loss, and bone defects".[41]

Popular culture

Perhaps one of the earliest influences of progeria on popular culture occurred in the 1922 short story The Curious Case of Benjamin Button by F. Scott Fitzgerald (and later released as a feature film in 2008). The main character, Benjamin Button, is born as a seventy-year-old man and ages backwards; it has been suggested that this was inspired by progeria.[42]

Charles Dickens may have described a case of progeria in the family of Smallweed of Bleak House, specifically in the grandfather and his grandchildren Judy and twin brother Bart.[43]

A Bollywood movie, Paa, was made about the condition; in it, the lead (Amitabh Bachchan) played an 11-year-old child affected by progeria.

The movies Renaissance and Jack deal with progeria.

In episode sixteen of the first season of the television show The X-Files, the corrupt doctor had experimented on children with Progeria.

In the 4 book series Otherland, by Tad Williams, one of the main characters suffers from progeria.

See also

- Werner syndrome, also called Adult progeria

- Biogerontology

- Degenerative disease

- Laminopathies

- Lipodystrophy

- Hayley Okines, an English girl with progeria who is known for spreading progeria awareness

- Lizzie Velasquez, an American motivational speaker whose medical condition approximates to Neonatal Progeroid Syndrome

- List of cutaneous conditions

References

- ^ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. p. 574. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Progeria, Incidence of Progeria and HGPS.

- ^ Ewell Steve Roach & Van S. Miller (2004). Neurocutaneous Disorders. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 052178153.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Kwang-Jen Hsiao (1998). Advances in Clinical Chemistry:33. Academic Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-12-010333-8.

- ^ McClintock D, Ratner D, Lokuge M; et al. (2007). Lewin, Alfred (ed.). "The Mutant Form of Lamin A that Causes Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Is a Biomarker of Cellular Aging in Human Skin". PLoS ONE. 2 (12): e1269. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001269. PMC 2092390. PMID 18060063.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Korf B (2008). "Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, aging, and the nuclear lamina". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (6): 552–5. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0800071. PMID 18256390.

- ^ Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S; et al. (2008). "Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (6): 592–604. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706898. PMC 2940940. PMID 18256394.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hutchinson J (1886). "Case of congenital absence of hair, with atrophic condition of the skin and its appendages, in a boy whose mother had been almost wholly bald from alopecia areata from the age of six". Lancet. I: 923.

- ^ Gilford H; Shepherd, RC (1904). "Ateleiosis and progeria: continuous youth and premature old age". Brit. Med. J. 2 (5157): 914–8. PMC 1990667. PMID 14409225.

- ^ a b c Cao, K. (June 2011). "Rapamycin Reverses Cellular Phenotypes and Enhances Mutant Protein Clearance in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome Cells". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (89): 89ra58. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002346. PMID 21715679.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Norris, J. (2011-10-21). "Aging Disease in Children Sheds Light on Normal Aging". UCSF web site. UCSF. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Best,BP (2009). "Nuclear DNA damage as a direct cause of aging" (PDF). Rejuvenation Research. 12 (3): 199–208. doi:10.1089/rej.2009.0847. PMID 19594328.

- ^ a b "Learning About Progeria". genome.gov. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "Progeria Research Foundation | The PRF Diagnostic Testing Program". Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ "Progeria: Treatment". MayoClinic.com. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ Sadeghi-Nejad A, Demmer L (2007). "Growth hormone therapy in progeria". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 20 (5): 633–7. PMID 17642424.

- ^ Scaffidi, P., Misteli, T. (2005). "Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome". Nat. Med. 11 (4): 440–5. doi:10.1038/nm1204. PMC 1351119. PMID 15750600.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meta M, Yang SH, Bergo MO, Fong LG, Young SG (2006). "Protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors and progeria". Trends Mol Med. 12 (10): 480–7. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.08.006. PMID 16942914.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clinical trial number NCT00425607 for "Phase II Trial of Lonafarnib (a Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor) for Progeria" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Staff writer (2011). "New Drug Hope for 'Aging' Kids". Nature. 333 (6039): 142. doi:10.1126/science.333.6039.142-b.

- ^ Capell BC; et al. (2005). "Inhibiting farnesylation of progerin prevents the characteristic nuclear blebbing of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102 (36): 12879–84. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506001102. PMC 1200293. PMID 16129833.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Wang Y; et al. (2010 Sep-Oct). "Blocking protein farnesylation improves nuclear shape abnormalities in keratinocytes of mice expressing the prelamin A variant in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome". Landes Bioscience. 1 (5): 432–9. doi:10.4161/nucl.1.5.12972. PMC 3037539. PMID 21326826.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hamilton, Jon (September 22, 2012). "Experimental Drug Is First To Help Kids With Premature-Aging Disease". NPR. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Steve Sternberg (April 16, 2003). "Gene found for rapid aging disease in children". USA Today. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ "Progeria". MayoClinic.com. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ Brown WT (1992). "Progeria: a human-disease model of accelerated aging". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 55 (6 Suppl): 1222S–4S. PMID 1590260.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hennekam RC (2006). "Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: review of the phenotype". Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 140 (23): 2603–24. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31346. PMID 16838330.

- ^ "Information Progeria". Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ^ Grant, Matthew (22 February 2005). "Family tormented by ageing disease". BBC News. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- ^ Hope, Alan (3 June 2009). "Face of Flanders: Michiel Vandeweert". Flanders Today. Retrieved on 3 September 2009.

- ^ First black child with aging disease hopes for future, Associated Press.

- ^ Capell BC, Collins FS, Nabel EG (2007). "Mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in accelerated aging syndromes". Circ. Res. 101 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153692. PMID 17615378.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Eriksson; et al. (2003). "Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome" (PDF). Nature. 423 (6937): 293–298. doi:10.1038/nature01629. PMID 12714972.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Family Crisis Becomes Scientific Quest", Science, 300(5621), 9 May 2003.

- ^ Lans H, Hoeijmakers JH (2006). "Cell biology: ageing nucleus gets out of shape". Nature. 440 (7080): 32–4. doi:10.1038/440032a. PMID 16511477.

- ^ Scaffidi P, Misteli T (May 19, 2006). "Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging". Science. 312 (5776): 1059–63. doi:10.1126/science.1127168. PMC 1855250. PMID 16645051.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Haithcock E, Dayani Y, Neufeld E; et al. (2005). "Age-related changes of nuclear architecture in Caenorhabditis elegans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (46): 16690–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506955102. PMC 1283819. PMID 16269543.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fong, L. G.; et al. (March 17, 2006). "A Protein Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor Ameliorates Disease in a Mouse Model of Progeria". Science. 311 (5767): 1621–3. doi:10.1126/science.1124875. PMID 16484451.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Sullivan; et al. (November 29, 1999). "Loss of A-type lamin expression compromises nuclear envelope integrity leading to muscular dystrophy". J Cell Biol. 147 (5): 913–20. doi:10.1083/jcb.147.5.913. PMC 2169344. PMID 10579712.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Varela I, Pereira S, Ugalde AP; et al. (2008). "Combined treatment with statins and aminobisphosphonates extends longevity in a mouse model of human premature aging". Nat. Med. 14 (7): 767–72. doi:10.1038/nm1786. PMID 18587406.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maloney WJ (2009). "Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria syndrome: its presentation in F. Scott Fitzgerald's short story 'The Curious Case of Benjamin Button' and its oral manifestations". J. Dent. Res. 88 (10): 873–6. doi:10.1177/0022034509348765. PMID 19783794.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Singh V (2010). "Reflections: neurology and the humanities. Description of a family with progeria by Charles Dickens". Neurology. 75 (6): 571. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7f6c. PMID 20697111.

External links

- Progeria : Aging starts in childhood

Media related to progeria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to progeria at Wikimedia Commons- Progeria Research Foundation

- Progeria News and Media Collection

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome

- Segmental progeria

- "A Time to Live" — Seattle Post-Intelligencer feature about Seth Cook, a child with progeria.

- "ABC 20/20 special news program about Progeria, with Barbara Walters"

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement