Waking Life: Difference between revisions

NeoBatfreak (talk | contribs) removed Category:Dreams in fiction; added Category:Dreams in films using HotCat |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

[[Ethan Hawke]] and [[Julie Delpy]] reprise their characters from ''[[Before Sunrise]]'' in one scene.<ref name=msnbc/><ref name=obsessed/> |

[[Ethan Hawke]] and [[Julie Delpy]] reprise their characters from ''[[Before Sunrise]]'' in one scene.<ref name=msnbc/><ref name=obsessed/> |

||

== |

==Plotaaaa== |

||

''Waking Life'' is about an unnamed<ref name=kehr/> young man living an ethereal existence that lacks transitions between everyday events and that eventually progresses toward an [[existential crisis]]. For most of the film he observes quietly but later participates actively in philosophical discussions involving other characters—ranging from quirky scholars and artists to everyday restaurant-goers and friends—about such issues as [[metaphysics]], [[free will]], [[social philosophy]], and the [[meaning of life]]. Other scenes do not even include the protagonist's presence, but rather, show an isolated person or couple speaking about such topics from a disembodied perspective. Along the way, the film touches also upon [[existentialism]], [[Situationist International|situationist]] politics, [[posthumanity]], the film theory of [[André Bazin]], and [[lucid dreaming]], and makes references to various celebrated intellectual and literary figures by name. |

''Waking Life'' is about an unnamed<ref name=kehr/> young man living an ethereal existence that lacks transitions between everyday events and that eventually progresses toward an [[existential crisis]]. For most of the film he observes quietly but later participates actively in philosophical discussions involving other characters—ranging from quirky scholars and artists to everyday restaurant-goers and friends—about such issues as [[metaphysics]], [[free will]], [[social philosophy]], and the [[meaning of life]]. Other scenes do not even include the protagonist's presence, but rather, show an isolated person or couple speaking about such topics from a disembodied perspective. Along the way, the film touches also upon [[existentialism]], [[Situationist International|situationist]] politics, [[posthumanity]], the film theory of [[André Bazin]], and [[lucid dreaming]], and makes references to various celebrated intellectual and literary figures by name. |

||

Revision as of 17:50, 20 March 2013

| Waking Life | |

|---|---|

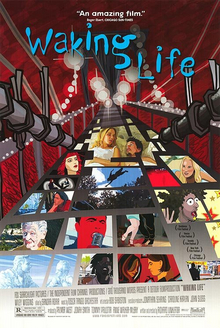

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Linklater |

| Written by | Richard Linklater |

| Produced by | Tommy Pallotta Jonah Smith Anne Walker-McBay Palmer West |

| Starring | Wiley Wiggins Kim Krizan Lorelei Linklater Trevor Jack Brooks Timothy "Speed" Levitch Alex Jones |

| Cinematography | Richard Linklater Tommy Pallotta |

| Edited by | Sandra Adair |

| Music by | Glover Gill |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Fox Searchlight Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3,176,880[1] |

Waking Life is an American animated film directed by Richard Linklater and released in 2001. The film focuses on the nature of dreams, consciousness, and existentialism.[2]

The film was entirely rotoscoped, although it was shot using digital video of live actors with a team of artists drawing stylized lines and colors over each frame with computers, rather than being filmed and traced onto cels on a light box.

Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy reprise their characters from Before Sunrise in one scene.[3][4]

Plotaaaa

Waking Life is about an unnamed[2] young man living an ethereal existence that lacks transitions between everyday events and that eventually progresses toward an existential crisis. For most of the film he observes quietly but later participates actively in philosophical discussions involving other characters—ranging from quirky scholars and artists to everyday restaurant-goers and friends—about such issues as metaphysics, free will, social philosophy, and the meaning of life. Other scenes do not even include the protagonist's presence, but rather, show an isolated person or couple speaking about such topics from a disembodied perspective. Along the way, the film touches also upon existentialism, situationist politics, posthumanity, the film theory of André Bazin, and lucid dreaming, and makes references to various celebrated intellectual and literary figures by name.

Gradually, the protagonist begins to realize that he is living out a perpetual dream, broken up only by occasional false awakenings. So far he is mostly a passive onlooker, though this changes during a chat with a passing woman who suddenly approaches him. After she eccentrically greets and shares her creative ideas with him, he reminds himself of his recent realization and of the fact that she must, therefore, be a figment of his own dreaming imagination. Afterwards, he starts to converse more openly with other dream characters as well; however, he ultimately begins to despair about being utterly trapped in this unending, irresolvable dream-state.

The protagonist's final talk is with a character who looks somewhat similar to the protagonist himself and whom he briefly encountered previously, earlier on in the film. This last conversation reveals this other character's understanding that reality may be only a single instant that the individual interprets falsely as time (and, thus, life); that living is simply the individual's constant negation of God's invitation to become one with the universe; that dreams offer a glimpse into the infinite nature of reality; and that in order to be free from the illusion called life, the individual need only to accept God's invitation—though he does not explicitly explain how this is achieved.

The protagonist is last seen walking into a driveway when he suddenly begins to levitate, paralleling a scene at the start of the film of a floating child in the same driveway. Unlike the child who grabbed firmly onto the handle of a nearby car, however, the protagonist uncertainly reaches toward the same handle but is too swiftly lifted above the vehicle and over the trees. He now rises into the endless blue expanse of the sky until he disappears from view altogether.

Cast

- Wiley Wiggins plays the protagonist.

The film features appearances from a wide range of actors and non-actors including:

- Eamonn Healy

- Speed Levitch

- Adam Goldberg

- Nicky Katt

- Alex Jones

- Steven Soderbergh

- Ethan Hawke

- Julie Delpy

- Steven Prince

- Caveh Zahedi

- Otto Hofmann

As well as American philosophers and writers:

Production

Adding to the dream-like effect, the film used an animation technique based on rotoscoping.[5] Animators overlaid live action footage (shot by Linklater) with animation that roughly approximates the images actually filmed.[5][6] This technique is similar in some respects to the rotoscope style of 1970s filmmaker Ralph Bakshi. Rotoscoping itself, however, was not Bakshi's invention, but that of experimental silent film maker Max Fleischer, who patented the process in 1917.[7] A variety of artists were employed, so the feel of the movie continually changes, and gets stranger as time goes on. The result is a surreal, shifting dreamscape.

The animators used inexpensive "off-the-shelf" Apple Macintosh computers. The film was mostly produced using Rotoshop, a custom-made rotoscoping program that creates blends between keyframe vector shapes (the name is a play on popular bitmap graphics editing software Photoshop, which also makes use of virtual "layers"), and created specifically for the production by Bob Sabiston. Linklater would again use this animation method for his 2006 film A Scanner Darkly.

Release

Waking Life premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2001, and was given a limited release in the United States on October 19, 2001.

Reception

Critical reaction to Waking Life has been mostly positive. It holds a rating of 80% across 137 reviews on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes — with critical consensus that "[t]he talky, animated Waking Life is a unique, cerebral experience" — and an average score of 82 out of 100 ("universal acclaim") on Metacritic, based on thirty-one reviews.[8][9] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four, describing it as "a cold shower of bracing, clarifying ideas."[10] Ebert later included the film on his ongoing list of "Great Movies."[11] Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly awarded the film an "A" rating, calling it "a work of cinematic art in which form and structure pursues the logic-defying (parallel) subjects of dreaming and moviegoing,"[12] while Stephen Holden of The New York Times said it was "so verbally dexterous and visually innovative that you can't absorb it unless you have all your wits about you."[13] Dave Kehr of The New York Times found the film to be "lovely, fluid, funny" and stated that it "never feels heavy or over-ambitious."[2]

Conversely, J. Hoberman of The Village Voice felt that Waking Life "doesn't leave you in a dream ... so much as it traps you in an endless bull session."[14] Frank Lovece felt the film was "beautifully drawn" but called its content "pedantic navel-gazing."[15]

Nominated for numerous awards, mainly for its technical achievements, Waking Life won the National Society of Film Critics award for "Best Experimental Film," the New York Film Critics Circle award for "Best Animated Film", and the "CinemAvvenire" award at the Venice Film Festival for "Best Film." It was also nominated for the Golden Lion, the festival's main award.

The American Film Institute nominated Waking Life for its Top 10 Animated Films list.[16]

Home media

The film was released on DVD in North America in May 2002. Special features included several commentaries, documentaries, interviews, trailers and deleted scenes, as well as the short film Snack and Drink. A bare-bones DVD with no special features was released in Region 2 in February 2003.

Soundtrack

The Waking Life OST was performed and written by Glover Gill and the Tosca Tango Orchestra, except for Frédéric Chopin's Nocturne in E-flat major, Op. 9, No. 2. The soundtrack was relatively successful. Featuring the nuevo tango style, it bills itself "the 21st Century Tango." The tango contributions were influenced by the music of the Argentine "father of new tango" Ástor Piazzolla.

The trance act called 1200 Micrograms samples lines from the movie Waking Life in their song:"Acid for Nothing"; a trance remix of Dire Straits' Money for Nothing.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Waking Life (2001) – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c Kehr, Dave (October 14, 2001). "FILM; Waking Up While Still Dreaming". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ "Hawke and Delpy reunite 'Before Sunset' - More news and other features". MSNBC. July 5, 2004. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ DigitallyObsessed. "dOc Scenes Interview: Dream Life: An Interview With Julie Delpy". Digitallyobsessed.com. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ a b Silverman, Jason (October 19, 2001). "Animating a Waking Life". Wired. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- ^ Howe, Desson (October 26, 2001). "Aroused by Waking Life". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ US patent 1242674, Max Fleischer, "Method of producing moving-picture cartoons", issued 1917-10-09

- ^ "Waking Life Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ "Waking Life (2001): Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 19, 2001). "Waking Life". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 11, 2009). "Waking Life". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (October 18, 2001). "Waking Life". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (October 12, 2001). "Surreal Adventures Somewhere Near the Land of Nod". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved May 26, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Hoberman, J. (October 16, 2001). "New York Movies – Sleep With Me". The Village Voice. Village Voice Media. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Lovece, Frank. "Waking Life Review". TVGuide.com. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ AFI's 10 Top 10 Ballot

References

- Jones, Kent (2007). Physical Evidence: Selected Film Criticism. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 76–78. ISBN 0-8195-6844-9.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (2004). "Good Vibrations". Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7840-3.

External links

- 2001 films

- American films

- English-language films

- American animated films

- Fox Searchlight Pictures animated films

- American avant-garde and experimental films

- Existentialist works

- Films directed by Richard Linklater

- Films shot digitally

- Films shot in Texas

- Films shot in Austin, Texas

- Films shot in San Antonio, Texas

- Fox Searchlight Pictures films

- Dreams in films

- Films about philosophy