3 Juno: Difference between revisions

→External links: Ah, Link does not really work.... |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

| url= http://www.psi.edu/pds/resource/lc.html |

| url= http://www.psi.edu/pds/resource/lc.html |

||

| accessdate= 2007-03-15 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070128183706/http://www.psi.edu/pds/resource/lc.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 2007-01-28}}</ref> |

| accessdate= 2007-03-15 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070128183706/http://www.psi.edu/pds/resource/lc.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 2007-01-28}}</ref> |

||

| spectral_type=[[S-type asteroid]]<ref name="jpldata"/><ref name="tax">{{cite web | last= Neese | first= C. | coauthors= Ed. | title= Asteroid Taxonomy.EAR-A-5-DDR-TAXONOMY-V5.0. | publisher= [[Planetary Data System|NASA Planetary Data System]] | year= 2005 | url |

| spectral_type=[[S-type asteroid]]<ref name="jpldata"/><ref name="tax">{{cite web | last= Neese | first= C. | coauthors= Ed. | title= Asteroid Taxonomy.EAR-A-5-DDR-TAXONOMY-V5.0. | publisher= [[Planetary Data System|NASA Planetary Data System]] | year= 2005 | url= http://web.archive.org/web/20060905083536/http://www.psi.edu/pds/asteroid/EAR_A_5_DDR_TAXONOMY_V5_0/data/taxonomy05.tab| accessdate= 2013-12-24 |

||

| magnitude = 7.4<ref name="AstDys-Juno">{{cite web |

| magnitude = 7.4<ref name="AstDys-Juno">{{cite web |

||

|title=AstDys (3) Juno Ephemerides |

|title=AstDys (3) Juno Ephemerides |

||

Revision as of 20:53, 24 December 2013

Juno seen at four wavelengths. A large crater appears dark at 934 nm. | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Karl Ludwig Harding |

| Discovery date | September 1, 1804 |

| Designations | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈdʒuːnoʊ/ |

Named after | Juno (Latin: Iūno) |

| none | |

| Main belt (Juno clump) | |

| Adjectives | Junonian /dʒuːˈnoʊniən/[1] |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| Epoch November 30, 2008 (JD 2454800.5) | |

| Aphelion | 3.356 AU (502.050 Gm) |

| Perihelion | 1.988 AU (297.40 Gm) |

| 2.672 AU (399.725 Gm) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.2559 |

| 4.37 a (1595.4 d) | |

Average orbital speed | 17.93 km/s |

| 256.8° | |

| Inclination | 12.968° |

| 169.96° | |

| 247.93° | |

| Proper orbital elements[3] | |

Proper semi-major axis | 2.6693661 AU |

Proper eccentricity | 0.2335060 |

Proper inclination | 13.2515192° |

Proper mean motion | 82.528181 deg / yr |

Proper orbital period | 4.36215 yr (1593.274 d) |

Precession of perihelion | 43.635655 arcsec / yr |

Precession of the ascending node | −61.222138 arcsec / yr |

| Physical characteristics | |

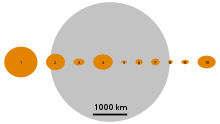

| Dimensions | 320×267×200 km[4] (233 km)[2] |

| Mass | 2.67 ×1019 kg[4] |

Mean density | 2.98 ± 0.55 g/cm³[4] |

| 0.12 m/s² | |

| 0.18 km/s | |

| 7.21 hr[2] (0.3004 d)[5] | |

| Albedo | 0.238 (geometric)[2][6] |

| Temperature | ~163 K max: 301 K (+28°C)[7] |

Spectral type | S-type asteroid[2]Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).[8] to 11.55 |

| 5.33[2][6] | |

| 0.30" to 0.07" | |

Juno, minor-planet designation 3 Juno in the Minor Planet Center catalogue system, was the third asteroid to be discovered and is one of the larger main-belt asteroids, being one of the two largest stony (S-type) asteroids, along with 15 Eunomia. It is estimated to contain 1% of the total mass of the asteroid belt.[9] Juno was discovered on September 1, 1804, by German astronomer Karl L. Harding.

Name

3 Juno is named after the mythological Juno, the highest Roman goddess. The adjectival form is Junonian (jūnōnius).

With two exceptions, 'Juno' is the international name, subject to local variation: Italian Giunone, French Junon, Russian Yunona, etc.[* 1] Its planetary symbol is ③. An older symbol, still occasionally seen, is ⚵ (![]() ).

).

Characteristics

Juno is one of the larger asteroids, perhaps tenth by size and containing approximately 1.0% the mass of the entire asteroid belt.[10] It is the second-most-massive S-type asteroid after 15 Eunomia.[4] Even so, Juno has only 3% the mass of Ceres.[4]

Amongst S-type asteroids, Juno is unusually reflective, which may be indicative of distinct surface properties. This high albedo explains its relatively high apparent magnitude for a small object not near the inner edge of the asteroid belt. Juno can reach +7.5 at a favourable opposition, which is brighter than Neptune or Titan, and is the reason for it being discovered before the larger asteroids Hygiea, Europa, Davida, and Interamnia. At most oppositions, however, Juno only reaches a magnitude of around +8.7[11]—only just visible with binoculars—and at smaller elongations a 3-inch (76 mm) telescope will be required to resolve it.[12] It is the main body in the Juno family.

Juno was originally considered a planet, along with 1 Ceres, 2 Pallas, and 4 Vesta.[13] In 1811, Schröter estimated Juno to be as large as 2290 km in diameter.[13] All four were re-classified as asteroids as additional asteroids were discovered. Juno's small size and irregular shape preclude it from being designated a dwarf planet.

Juno orbits at a slightly closer mean distance to the Sun than Ceres or Pallas. Its orbit is moderately inclined at around 12° to the ecliptic, but has an extreme eccentricity, greater than that of Pluto. This high eccentricity brings Juno closer to the Sun at perihelion than Vesta and further out at aphelion than Ceres. Juno had the most eccentric orbit of any known body until 33 Polyhymnia was discovered in 1854, and of asteroids over 200 km in diameter only 324 Bamberga has a more eccentric orbit.[14]

Juno rotates in a prograde direction with an axial tilt of approximately 50°.[15] The maximum temperature on the surface, directly facing the Sun, was measured at about 293 K on October 2, 2001. Taking into account the heliocentric distance at the time, this gives an estimated maximum temperature of 301 K (+28 °C) at perihelion.[7]

Spectroscopic studies of the Junonian surface permit the conclusion that Juno could be the progenitor of chondrites, a common type of stony meteorite composed of iron-bearing silicates such as olivine and pyroxene.[16] Infrared images reveal that Juno possesses an approximately 100 km-wide crater or ejecta feature, the result of a geologically young impact.[17][18]

Observations

Juno was the first asteroid for which an occultation was observed. It passed in front of a dim star (SAO 112328) on February 19, 1958. Since then, several occultations by Juno have been observed, the most fruitful being the occultation of SAO 115946 on December 11, 1979, which was registered by 18 observers.[19]

Radio signals from spacecraft in orbit around Mars and on its surface have been used to estimate the mass of Juno from the tiny perturbations induced by it onto the motion of Mars.[20] Juno's orbit appears to have changed slightly around 1839, very likely due to perturbations from a passing asteroid, whose identity has not been determined. An alternate but less likely explanation is an impact by a sizeable body.[21]

In 1996, Juno was imaged by the Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory at visible and near-IR wavelengths, using adaptive optics. The images spanned a whole rotation period and revealed an irregular shape and a dark albedo feature, interpreted as a fresh impact site.[18]

Juno moving across background stars. |

Juno during opposition in 2009. |

Occultations

3 Juno occulted the magnitude 11.3 star PPMX 9823370 on July 29, 2013,[22] and 2UCAC 30446947 on July 30, 2013.[23]

See also

Notes

- ^ The exceptions are Greek, where the name was translated to its Hellenic equivalent, Hera (3 Ήρα), as in the cases of 1 Ceres and 4 Vesta; and Chinese, where it is called the 'marriage-god(dess) star' (婚神星 hūnshénxīng). This contrasts with the goddess Juno, for which Chinese uses the Latin name (朱諾 zhūnuò).

References

- ^ "Junonian". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 3 Juno". 2008-07-30 last obs. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "AstDyS-2 Juno Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 2011-10-01.

- ^ a b c d e Jim Baer (2008). "Recent Asteroid Mass Determinations". Personal Website. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- ^

Harris, A. W. (2006). "Asteroid Lightcurve Derived Data. EAR-A-5-DDR-DERIVED-LIGHTCURVE-V8.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 2007-01-28. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Davis, D. R. (2002). "Asteroid Albedos. EAR-A-5-DDR-ALBEDOS-V1.1". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Lim, Lucy F. (2005). "Thermal infrared (8-13 µm) spectra of 29 asteroids: the Cornell Mid-Infrared Asteroid Spectroscopy (MIDAS) Survey". Icarus. 173 (2): 385–408. Bibcode:2005Icar..173..385L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.08.005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bright Minor Planets 2005". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 2010-08-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pitjeva, E. V. (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants" (PDF). Solar System Research. 39 (3): 176. Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V.; Precise determination of the motion of planets and some astronomical constants from modern observations, in Kurtz, D. W. (Ed.), Proceedings of IAU Colloquium No. 196: Transits of Venus: New Views of the Solar System and Galaxy, 2004

- ^

Odeh, Moh'd. "The Brightest Asteroids". The Jordanian Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "What Can I See Through My Scope?". Ballauer Observatory. 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ a b Hilton, James L (2007-11-16). "When did asteroids become minor planets?". U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 2008-03-24. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ "MBA Eccentricity Screen Capture". JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ The north pole points towards ecliptic coordinates (β, λ) = (27°, 103°) within a 10° uncertainty.

Kaasalainen, M. (2002). "Models of Twenty Asteroids from Photometric Data" (PDF). Icarus. 159 (2): 369–395. Bibcode:2002Icar..159..369K. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6907.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Gaffey, Michael J. (1993). "Mineralogical variations within the S-type asteroid class". Icarus. 106 (2): 573. Bibcode:1993Icar..106..573G. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1194.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

"Asteroid Juno Has A Bite Out Of It". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 2003-08-06. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Baliunas, Sallie (2003). "Multispectral analysis of asteroid 3 Juno taken with the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory" (PDF). Icarus. 163 (1): 135–141. Bibcode:2003Icar..163..135B. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00049-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Millis, R. L. (1981). "The diameter of Juno from its occultation of AG+0°1022". Astronomical Journal. 86: 306–313. Bibcode:1981AJ.....86..306M. doi:10.1086/112889.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Pitjeva, E. V. (2004). "Estimations of masses of the largest asteroids and the main asteroid belt from ranging to planets, Mars orbiters and landers". 35th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 18–25 July 2004, in Paris, France. p. 2014.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Hilton, James L. (1999). "US Naval Observatory Ephemerides of the Largest Asteroids". Astronomical Journal. 117 (2): 1077–1086. Bibcode:1999AJ....117.1077H. doi:10.1086/300728. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Asteroid Occultation Updates - Jul 29, 2013

- ^ Asteroid Occultation Updates - Jul 30, 2013.

External links

- JPL Ephemeris

- Well resolved images from four angles taken at Mount Wilson observatory

- Shape model deduced from light curve

- Asteroid Juno Grabs the Spotlight

- "Elements and Ephemeris for (3) Juno". Minor Planet Center. (displays Elong from Sun and V mag for 2011)