Inga dams: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Forreal123 to version by 178.83.236.22. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1944577) (Bot) |

No edit summary Tag: gettingstarted edit |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Current Dams== |

==Current Dams== |

||

{{further|History of the Inga Dams}} |

{{further|History of the Inga Dams}} |

||

These two hydroelectric dams, Inga I and Inga II, currently operate at a low output. The existing dams have a total installed capacity of 1,775 MW. They were built under former president [[Mobutu Sese Seko]] as part of the [[Inga–Shaba]] project. |

|||

==Expansion plans== |

==Expansion plans== |

||

Revision as of 15:08, 16 September 2014

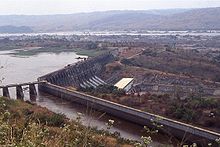

The Inga Dams are two hydroelectric dams connected to the largest waterfall in the world, Inga Falls. They are located in western Democratic Republic of the Congo and 140 miles southwest of Kinshasa. The Congo River drops 96 metres (315 ft).[1]

Current Dams

These two hydroelectric dams, Inga I and Inga II, currently operate at a low output. The existing dams have a total installed capacity of 1,775 MW. They were built under former president Mobutu Sese Seko as part of the Inga–Shaba project.

Expansion plans

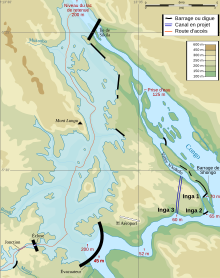

There are expansion plans to create a third Inga damn, Inga III. Projections indicate that once completed, Inga III would generate 4,500 megawatts of electricity. Inga III is the centerpiece of the Westcor partnership which envisions the interconnection of the electric grids of the DRC, Namibia, Angola, Botswana, and South Africa. The World Bank, the African Development Bank, the European Investment Bank, JFPI Corporation, bilateral donors, and the southern African power companies have all expressed interest in pursuing the project which is estimated to cost USD $80 billion.

The Grand Inga Dam would generate 39,000 MW – and would significantly boost the energy needs of the African continent at a cost of $80 billion. Connecting Inga to a continent-wide electricity grid for main population centers would cost $10 billion more (est. 2000) and would be the world's largest hydroelectric project. Critics contend the huge amounts of money required for the project would be better spent with smaller scale, localized energy projects that would better meet the needs of Africa's poor majority. A study from Oxford University supports this cautious approach by showing that the average cost overrun for 245 large dams in 65 countries across six continents is 96% in real terms.[2]

The NEPAD (New Partnership for Africa's Development), with significant involvement of South African electric power company ESKOM, has suggested to start the Grand Inga project in 2010.[3][4] At an installed capacity of 39,000 MW, the Grand Inga alone could produce 250 TWh annually, or a total of 370 TWh annually for the whole site. In 2005, Africa's annual electricity production was 550 TWh (600 kWh per capita). If the dam were to be completed somewhere in the 2020s, the continent might produce more than 1000 TWh, 20% of total estimated energy requirements, at that time.

Africa's electric energy disparity

This section may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (September 2013) |

The electric energy disparity in the continent makes tropical Africa the part most in need of energy projects such as Great Inga. The 550 TWh were produced in 2005 (62.7GW) as follows:

- 230 TWh p.a. / 26.2 GW (42%): South Africa with 5.5% of the continent population (4500 kWh p.a. per capita / 513 W per capita)

- 150 TWh p.a. /17.1 GW (27%): Five northern African nations with 16.7% of the continent population: Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and Libya (1000 kWh p.a. per capita /114 W per capita)

- 170 TWh p.a. / 19.4 GW (31%): The rest of the continent or inter-tropical Africa with 77.8% of the continent population (250 kWh p.a. per capita / 29W per capita)

This gives an average total generation of 63 GW to be compared to the 43.5 GW the Inga and the Grand Inga would generate.

There is a false belief that the Grand Inga can produce enough electricity for the whole continent.[5] That was true before the 1990s.[6][7] The continent has an annual economic growth of 5%. In 2005, six nations from the north and south regions with 22% of African population used 70% of the total electric energy produced. The remaining 47 nations with 78% of African population shared 30% equivalent to a per capita of 250 kWh on average. Those 47 countries are working hard to meet the Millennium Development Goals in 2015.[8] Doubling their per capita electric production in the next decade to 500 kWh means that the continent will need at least 1000 TWh from its 550 TWh in 2005.

According to some, Grand Inga would be too large a proportion of the African demand (43.5 GW combined output compared to a load of 63 GW) to be a practical power source without interconnection, for example by wide area synchronous grid, to other power grids. Any large-scale failure of the dam or its connections to the grid, such as 2009 Brazil and Paraguay blackout (17GW), or the 2009 Sayano–Shushenskaya hydro accident in Siberia (6.4 GW), would plunge large parts of Africa into a power failure due to the very large and sudden power loss (the Siberia failure had a disastrous effect on local aluminium smelters). By this argument, full utilization requires interconnection with Europe such that some power goes to Europe at some times, but that Europe can also back feed power to Africa. This increases the stability of both systems and reduces overall costs.[9][10]

Three international consortiums are bidding for the contract to build the dam, known as Inga III, and sell the power it generates, estimated at 4,800 MW. This is nearly three times the power produced from Inga's two existing dams, which are decades old and have been crippled by neglect, government debt and risk-averse investors. The World Bank said under the current plan, South Africa would buy 2,500 megawatts from Inga III, and another 1,300 megawatts will be sold to Congo's power-starved mining industry. The remaining 1000 megawatts would go to the national utility SNEL, helping provide power to an estimated 7 million people around Kinshasa, Congo's capital, and covering all the projected unmet electricity needs there by 2025.[11]

References

- ^ Fizzy Energy. The worlds tallest and largest waterfalls. September 23, 2009.

- ^ Atif Ansar, Bent Flyvbjerg, Alexander Budzier and Daniel Lunn, “Should We Build More Large Dams? The Actual Cost of Hydropower Megaproject Development”, Energy Policy, March 2014, pp.1-14

- ^ "IRIN Africa | SOUTHERN AFRICA: New plant to bring regional power on stream | SOUTHERN AFRICA | Economy | Environment | Other". Irinnews.org. 14 November 2003. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "businessinafrica.net". businessinafrica.net. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,20867,21396540-30417,00.html

- ^ "IEEE Xplore – African electricity infrastructure interconnections and electricity exchanges" (PDF). Ieeexplore.ieee.org. doi:10.1109/60.900510. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "SciTech Connect:". Osti.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Content Not Found – Mail & Guardian". Mg.co.za. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Andrews, Dave (1 August 2009). "Vision 2020 and beyond – Dr. Gregor Czisch Ex Kassell University discussed the integration of African Power production internally and with Europe to fully exploit the vast hydro power available at the Inga Dam site". Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Energy Research Group - Vision 2020 and beyond – Dr. Gregor Czisch Ex Kassell University discussed the integration of African Power production internally and with Europe to fully exploit the vast hydro power available at the Inga Dam site

- ^ "World Bank approves funds to study Congo's Inga dam".