Indus script: Difference between revisions

Bladesmulti (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

→Corpus: add seal materials |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

|isbn=978-2-8653830-1-6 |

|isbn=978-2-8653830-1-6 |

||

|accessdate=2013-05-27}} |

|accessdate=2013-05-27}} |

||

</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Whitehouse|first=David|date=1999-05-04|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/334517.stm|title='Earliest writing' found|publisher=[[BBC]]|work=[[BBC News Online]]|accessdate=2014-08-21|deadurl=no|archivedate=2014-08-21|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6RztiugCy}}</ref> In the [[Mature Harappan]] period, from about 2600 BC to 1900 BC, strings of Indus signs are commonly found on flat, rectangular [[stamp seal]]s as well as many other objects including tools, tablets, ornaments and pottery. These signs were applied in many ways, including carving, chiseling, painting and embossing, and the objects themselves were also made of many different materials, such as bone, shell, terracotta, sandstone, copper and gold.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|encyclopedia=Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions|volume=Volume 3: New material, untraced objects, and collections outside India and Pakistan - Part 1: Mohenjo-daro and Harappa|url=http://www.harappa.com/indus/Kenoyer-Meadow-2010-HARP.pdf|editor1-first=Asko|editor1-last=Parpola|editor2-first=B.M.|editor2-last=Pande|editor3-first=Petteri|editor3-last=Koskikallio|title=Inscribed Objects from Harappa Excavations 1986-2007|first=J. Mark|last=Kenoyer|first2=Richard H.|last2=Meadow|page=xlviii|date=2010|publisher=Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia}}</ref> |

</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Whitehouse|first=David|date=1999-05-04|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/334517.stm|title='Earliest writing' found|publisher=[[BBC]]|work=[[BBC News Online]]|accessdate=2014-08-21|deadurl=no|archivedate=2014-08-21|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6RztiugCy}}</ref> In the [[Mature Harappan]] period, from about 2600 BC to 1900 BC, strings of Indus signs are commonly found on flat, rectangular [[stamp seal]]s as well as many other objects including tools, tablets, ornaments and pottery. These signs were applied in many ways, including carving, chiseling, painting and embossing, and the objects themselves were also made of many different materials, such as soapstone, bone, shell, terracotta, sandstone, copper, silver and gold.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|encyclopedia=Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions|volume=Volume 3: New material, untraced objects, and collections outside India and Pakistan - Part 1: Mohenjo-daro and Harappa|url=http://www.harappa.com/indus/Kenoyer-Meadow-2010-HARP.pdf|editor1-first=Asko|editor1-last=Parpola|editor2-first=B.M.|editor2-last=Pande|editor3-first=Petteri|editor3-last=Koskikallio|title=Inscribed Objects from Harappa Excavations 1986-2007|first=J. Mark|last=Kenoyer|first2=Richard H.|last2=Meadow|page=xlviii|date=2010|publisher=Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia}}</ref> |

||

===Late Harappan=== |

===Late Harappan=== |

||

Revision as of 21:11, 16 February 2015

| Indus script | |

|---|---|

| Script type | Undeciphered

Bronze Age writing |

Time period | 3500–1900 BCE[1] [2][3] |

| Direction | Right-to-left script, boustrophedon |

| Languages | Unknown (see Harappan language) |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Inds (610), Indus (Harappan) |

The Indus script (also Harappan script) is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilization during the Kot Diji and Mature Harappan periods between the 35th and 20th centuries BC. Most inscriptions are extremely short. It is not clear if these symbols constitute a script used to record a language, and the subject of whether the Indus symbols were a writing system is controversial. In spite of many attempts at decipherment,[4] it is undeciphered, and no underlying language has been identified. There is no known bilingual inscription. The script does not show any significant changes over time.

The first publication of a seal with Harappan symbols dates to 1873, in a drawing by Alexander Cunningham. Since then, over 4,000 inscribed objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia. In the early 1970s, Iravatham Mahadevan published a corpus and concordance of Indus inscriptions listing 3,700 seals and 417 distinct signs in specific patterns. The average inscription contains five signs, and the longest inscription is only 17 signs long. He also established the direction of writing as right to left.[5]

Some early scholars, starting with Cunningham in 1877, thought that the system was the archetype of the Brāhmī script. Cunningham's ideas were supported by scholars, such as G.R. Hunter, S. R. Rao, F. Raymond Allchin, John Newberry,[6] Iravatham Mahadevan,[7][8] Krishna Rao,[9] some of whom continue to argue for an Indus predecessor of the Brahmic script.

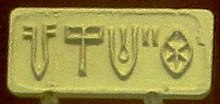

Corpus

Early examples of the symbol system are found in an Early Harappan and Indus civilisation context, dated to possibly as early as the 35th century BC.[10][11] In the Mature Harappan period, from about 2600 BC to 1900 BC, strings of Indus signs are commonly found on flat, rectangular stamp seals as well as many other objects including tools, tablets, ornaments and pottery. These signs were applied in many ways, including carving, chiseling, painting and embossing, and the objects themselves were also made of many different materials, such as soapstone, bone, shell, terracotta, sandstone, copper, silver and gold.[12]

Late Harappan

After 1900 BC, the systematic use of the symbols ended, after the final stage of the Mature Harappan civilization. A few Harappan signs have been claimed to appear until as late as around 1100 BC (the beginning of the Indian Iron Age). Onshore explorations near Bet Dwarka in Gujarat revealed the presence of late Indus seals depicting a 3-headed animal, earthen vessel inscribed in what is claimed to be a late Harappan script, and a large quantity of pottery similar to Lustrous Red Ware bowl and Red Ware dishes, dish-on-stand, perforated jar and incurved bowls which are datable to the 16th century BC in Dwarka, Rangpur and Prabhas. The thermoluminescence date for the pottery in Bet Dwaraka is 1528 BC. This evidence has been used to claim that a late Harappan script was used until around 1500 BC.[13]

In May 2007, the Tamil Nadu Archaeological Department found pots with arrow-head symbols during an excavation in Melaperumpallam near Poompuhar. These symbols are claimed to have a striking resemblance to seals unearthed in Mohenjo-daro Pakistan in the 1920s.[14]

In one purported decipherment of the script, the Indian archaeologist S. R. Rao argued that the late phase of the script represented the beginning of the alphabet. He notes a number of striking similarities in shape and form between the late Harappan characters and the Phoenician letters, arguing than the Phoenician script evolved from the Harappan script, challenging the classical theory that the first alphabet was Proto-Sinaitic.[15]

Characteristics

The characters are largely pictorial but includes many abstract signs. The inscriptions are thought to have been mostly written from right to left, but sometimes follows a boustrophedonic style. The number of principal signs is about 400, comparable to the typical sign inventory of a logo-syllabic script.

Decipherability question

An opposing hypothesis that has been offered by Michael Witzel and Steve Farmer, is that these symbols were nonlinguistic signs which instead symbolised families, clans, gods, and religious concepts.[16] In a 2004 article, Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel presented a number of arguments that the Indus script is nonlinguistic, principal among them being the extreme brevity of the inscriptions, the existence of too many rare signs (increasing over the 700-year period of the Mature Harappan civilization), and the lack of the random-looking sign repetition typical of language.[17]

Asko Parpola, reviewing the Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel thesis in 2005, states that their arguments "can be easily controverted".[18] He cites the presence of a large number of rare signs in Chinese, and emphasizes that there is "little reason for sign repetition in short seal texts written in an early logo-syllabic script". Revisiting the question in a 2007 lecture,[19] Parpola takes on each of the 10 main arguments of Farmer et al., presenting counterarguments for each. He states that "even short noun phrases and incomplete sentences qualify as full writing if the script uses the rebus principle to phonetize some of its signs".

A 2009 paper[20] published by Rajesh P N Rao, Iravatham Mahadevan, and others in the journal Science challenged the argument that the Indus script might have been a nonlinguistic symbol system. The paper concludes that the conditional entropy of Indus inscriptions closely matches those of linguistic systems like the Sumerian logo-syllabic system, Old Tamil, Rig Vedic Sanskrit etc., though they are careful to stress that this does not mean that the script is linguistic. A follow-up study elaborated on these claims.[21] Sproat in turn notes a number of misunderstandings in Rao et al., a lack of discriminative power in their model, and that applying their model to known non-linguistic systems such as Mesopotamian deity symbols produces similar results to the Indus script. Their responses, and Sproat's reply, were published in Computational Linguistics in December 2010.[22] The June 2014 issue of Language carries a paper by Sproat that provides further evidence that Rao "et al."'s methodology is flawed.[23]

Attempts at decipherment

Over the years, numerous decipherments have been proposed, but there is no established scholarly consensus.[24] The following factors are usually regarded as the biggest obstacles for a successful decipherment:

- The underlying language has not been identified though some 300 loanwords in the Rigveda are a good starting point for comparison.[25][26]

- The average length of the inscriptions is less than five signs, the longest being only 17 signs (and a sealing of combined inscriptions of just 27 signs).[27]

- No bilingual texts (like a Rosetta Stone) have been found.

The topic is popular among amateur researchers, and there have been various (mutually exclusive) decipherment claims.[28]

Dravidian hypothesis

The Russian scholar Yuri Knorozov surmised that the symbols represent a logosyllabic script and suggested, based on computer analysis, an underlying agglutinative Dravidian language as the most likely candidate for the underlying language.[29] Knorozov's suggestion was preceded by the work of Henry Heras, who suggested several readings of signs based on a proto-Dravidian assumption.[30]

The Finnish scholar Asko Parpola writes that the Indus script and Harappan language "most likely to have belonged to the Dravidian family".[31] Parpola led a Finnish team in the 1960s-80s that vied with Knorozov's Soviet team in investigating the inscriptions using computer analysis. Based on a proto-Dravidian assumption, they proposed readings of many signs, some agreeing with the suggested readings of Heras and Knorozov (such as equating the "fish" sign with the Dravidian word for fish "min") but disagreeing on several other readings. A comprehensive description of Parpola's work until 1994 is given in his book Deciphering the Indus Script.[32] The discovery in Tamil Nadu of a late Neolithic (early 2nd millennium BC, i.e. post-dating Harappan decline) stone celt allegedly marked with Indus signs has been considered by some to be significant for the Dravidian identification.[33][34]

Iravatham Mahadevan, who supports the Dravidian hypothesis, says, "we may hopefully find that the proto-Dravidian roots of the Harappan language and South Indian Dravidian languages are similar. This is a hypothesis [...] But I have no illusions that I will decipher the Indus script, nor do I have any regret".[35]

"Sanskritic" hypothesis

Indian archaeologist Shikaripura Ranganatha Rao claimed to have deciphered the Indus script. Postulating uniformity of the script over the full extent of Indus-era civilization, he compared it to the Phoenician Alphabet, and assigned sound values based on this comparison. His decipherment results in an "Sanskritic" reading, including the numerals aeka, tra, chatus, panta, happta/sapta, dasa, dvadasa, sata (1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 12, 100).[36]

John E. Mitchiner, has dismissed some of these attempts at decipherment. Mitchiner mentions that "a more soundly-based but still greatly subjective and unconvincing attempt to discern an Indo-European basis in the script has been that of Rao".[37]

Encoding

The Indus symbols have been assigned the ISO 15924 code "Inds". It was proposed for encoding in Unicode's Supplementary Multilingual Plane in 1999; however, the Unicode Consortium still list the proposal in pending status.[38]

See also

Notes

- ^ "'Earliest writing' found". Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ "Evidence for Indus script dated to ca. 3500 BCE". Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Edwin Bryant. The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University. p. 178.

- ^ (Possehl, 1996)

- ^ "Write signs for Indus script?". Nature India. 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ "Indus script monographs - Volumes 1-7", p.10-20, 1980, John Newberry

- ^ "Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions", p.6, Jagat Pati Joshi, Asko Parpola

- ^ "Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume", p.277, Senarat Paranavitana, Leelananda Prematilleka, Johanna Engelberta van Lohuizen-De Leeuw, BRILL.

- ^ "An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology", Amalananda Ghosh, p.362, 1990

- ^ Meadow, Richard H.; Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (2001-07-02). "Excavations at Harappa 2000–2001: New insights on Chronology and City Organization". In Jarrige, C.; Lefèvre, V. (eds.). South Asian Archaeology 2001. Paris: Collège de France. ISBN 978-2-8653830-1-6. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|conference=ignored (help) - ^ Whitehouse, David (1999-05-04). "'Earliest writing' found". BBC News Online. BBC. Archived from the original on 2014-08-21. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kenoyer, J. Mark; Meadow, Richard H. (2010). "Inscribed Objects from Harappa Excavations 1986-2007" (PDF). In Parpola, Asko; Pande, B.M.; Koskikallio, Petteri (eds.). Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions. Vol. Volume 3: New material, untraced objects, and collections outside India and Pakistan - Part 1: Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. p. xlviii.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Sullivan, S. M. (2011) Indus Script Dictionary, page viii

- ^ Subramaniam, T. S. (May 1, 2006). "From Indus Valley to coastal Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ Robinson, Andrew. Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World's Undeciphered Scripts. 2002

- ^ Farmer et al. (2004)

- ^ Lawler, Andrew. 2004. The Indus script: Write or wrong? Science, 306:2026–2029.

- ^ (Parpola, 2005, p. 37)

- ^ (Parpola, 2008).

- ^ Rao, R.P.N.; et al. (6 May 2009). "Entropic Evidence for Linguistic Structure in the Indus Script" (PDF). Science. 324. doi:10.1126/science.1170391.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help) - ^ Rao, R.P.N. (April 2010). "Probabilistic Analysis of an Ancient Undeciphered Script" (PDF). IEEE Computer. 43 (4): 76–80. doi:10.1109/mc.2010.112.

- ^ http://www.mitpressjournals.org/toc/coli/36/4 Computational Linguistics, Volume 36, Issue 4, December 2010.

- ^ http://www.linguisticsociety.org/files/archived-documents/Sproat_Lg_90_2.pdf, R. Sproat, 2014, "A Statistical Comparison of Written Language and Nonlinguistic Symbol Systems". Language, Volume 90, Issue 2, June 2014.

- ^ Gregory L. Possehl. The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 136.

- ^ FBJ Kuiper, Aryans in the Rigveda, Amsterdam/Atlanta 1991

- ^ M. Witzel underlines the prefixing nature of these words and calls them Para-Munda,a language related to but not belonging to Proto-Munda; see: Witzel, M. Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic), EJVS Vol. 5,1, 1999, 1-67

- ^ Longest Indus inscription

- ^ see e.g. Egbert Richter and N. S. Rajaram for examples.

- ^ (Knorozov 1965)

- ^ (Heras, 1953)

- ^ Edwin Bryant. The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford. p. 183. ISBN 9780195169478.

- ^ (Parpola, 1994)

- ^ (Subramanium 2006; see also A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script in light of the Mayiladuthurai Stone Axe Discovery by I. Mahadevan (2006)

- ^ "Significance of Mayiladuthurai find - The Hindu". May 1, 2006.

- ^ Interview at Harrappa.com

- ^ Sreedharan (2007). A Manual of Historical Research Methodology. South Indian Studies. p. 268.

- ^ J.E. Mitchiner: Studies in the Indus Valley Inscriptions, p.5, with reference to S.R. Rao: Lothal and the Indus Civilisation (ch.10), Bombay 1978.

- ^ Everson 1999 and [1]

References

- Bryant, Edwin (2000), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate Oxford University Press.

- Everson, Michael (1999-01-29). "Proposal for encoding the Indus script in Plane 1 of the UCS" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farmer, Steve et al. (2004) The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization, Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS), vol. 11 (2004), issue 2 (Dec) [2] (PDF).

- Knorozov, Yuri V. (ed.) (1965) Predvaritel’noe soobshchenie ob issledovanii protoindiyskikh textov. Moscow.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham, Murukan In the Indus Script (1999)

- Mahadevan, Iravatham, Aryan or Dravidian or Neither? A Study of Recent Attempts to Decipher the Indus Script (1995–2000) EJVS (ISSN 1084-7561) vol. 8 (2002) issue 1 (March 8).[3]

- Heras, Henry. Studies in Proto-Indo-Mediterranean Culture, Bombay: Indian Historical Research Institute, 1953.

- Parpola, Asko et al. (1987-2010). Corpus of Indus seals and inscriptions, Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia (Academia scientiarum Fennica), 1987-2010.

- Parpola, Asko. Deciphering the Indus script Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Parpola, Asko (2005) Study of the Indus Script. 50th ICES Tokyo Session.

- Parpola, Asko (2008) Is the Indus script indeed not a writing system?. Published in Airāvati, Felicitation volume in honour of Iravatham Mahadevan, Chennai.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (1996). Indus Age: The Writing System. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3345-X..

- Walter Ashlin Fairservis (1992). The Harappan Civilization and Its Writing: A Model for the Decipherment of the Indus Script. BRILL.

- Rao, R.P.N. et al. (2009). "Entropic Evidence for Linguistic Structure in the Indus Script". Science, 29 May 2009.

- Rao, R.P.N. (2010). "Probabilistic Analysis of an Ancient Undeciphered Script". IEEE Computer, vol. 43(4), 76-80, April 2010.

- Sproat, R. (2014). "A Statistical Comparison of Written Language and Nonlinguistic Symbol Systems". "Language", vol. 90(2), 457-481, June 2014.

- Subramanian, T. S. (2006) "Significance of Mayiladuthurai find" in The Hindu, May 1, 2006.

- Wells, B. "An Introduction to Indus Writing" Independence, MO: Early Sites Research Society 1999.

- Keim, Brandon (2009) "Artificial Intelligence Cracks 4,000 Year Old Mystery" in WIRED

- Vidale, Massimo (2007) "The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel", Philosophy East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333–366.

External links

- Indus Script (ancientscripts.com)

- Indus Script (http://www.shangrilagifts.org/hp/indus.html - Comparison of Indus Valley Harappan 哈拉帕 and Ancient Chinese Jia-Gu-wen 甲骨文 "Bone Script")

- "Discovery of a century" in Tamil Nadu ("Discovery of a century" in Tamil Nadu )

- The Indus Script (From harappa.com)

- BBC - 'Earliest writing' found

- How come we can't decipher the Indus script? (from The Straight Dope)

- Iravatham Mahadevan, Towards a scientific study of the Indus Script

- "Studies in Indus Scripts - I" by S. Srikanta Sastri, published in Quarterly Journal of Mythic Society, Vol XXIV, No. 3

- "Studies in Indus Scripts - II" by S. Srikanta Sastri, published in Quarterly Journal of Mythic Society, Vol XXIV, No 4

- Script Image;Article

- Collection of essays about the Indus script (Steve Farmer)

- WIRED.com (WIRED.com)

- "Computers Unlock More Secrets Of The Mysterious Indus Valley Script". Science Daily. August 4, 2009..

- Rao, Rajesh (2011) "A Rosetta Stone for a Lost Language" TED Talks