Quasicrystal: Difference between revisions

m cleanup and gen fixes, typo(s) fixed: 2010's → 2010s using AWB |

|||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

*[[Archimedean solid]] |

*[[Archimedean solid]] |

||

*[[Fibonacci quasicrystal]] |

*[[Fibonacci quasicrystal]] |

||

*[[Frank Kasper phases]] |

|||

*[[Phason]] |

*[[Phason]] |

||

*[[Tessellation]] |

*[[Tessellation]] |

||

Revision as of 08:03, 26 February 2015

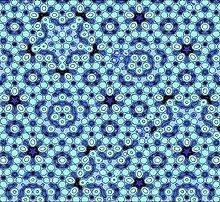

A quasiperiodic crystal, or quasicrystal, is a structure that is ordered but not periodic. A quasicrystalline pattern can continuously fill all available space, but it lacks translational symmetry. While crystals, according to the classical crystallographic restriction theorem, can possess only two, three, four, and six-fold rotational symmetries, the Bragg diffraction pattern of quasicrystals shows sharp peaks with other symmetry orders, for instance five-fold or seven-fold.

Aperiodic tilings were discovered by mathematicians in the early 1960s, and, some twenty years later, Alan Lindsay Mackay found to apply to predict a new kind of ordered structures (not allowed by traditional crystallography).[2][3] The discovery of these aperiodic forms in nature has produced a paradigm shift in the fields of crystallography. Quasicrystals had been investigated and observed earlier,[4] but, until the 1980s, they were disregarded in favor of the prevailing views about the atomic structure of matter. In 2009, after a dedicated search, a mineralogical finding, icosahedrite, offered evidence for the existence of natural quasicrystals.[5]

Roughly, an ordering is non-periodic if it lacks translational symmetry, which means that a shifted copy will never match exactly with its original. The more precise mathematical definition is that there is never translational symmetry in more than n – 1 linearly independent directions, where n is the dimension of the space filled, e.g., the three-dimensional tiling displayed in a quasicrystal may have translational symmetry in two dimensions. The ability to diffract comes from the existence of an indefinitely large number of elements with a regular spacing, a property loosely described as long-range order.

Experimentally, the aperiodicity is revealed in the unusual symmetry of the diffraction pattern — that is, symmetry of orders other than two, three, four, or six. The Mackay's 1981 and 1982 works[2][3] described and simulated this kind of experiment, for five-fold symmetry, showing the expected diffraction pattern. Next (yet in 1982) materials scientist Dan Shechtman observed that certain aluminium-manganese alloys produced the Mackay's diffractograms, which today are seen as revelatory of quasicrystal structures. Due to fear of the scientific community's reaction, it took him two years to publish the results[6][7] for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011.[8]

History

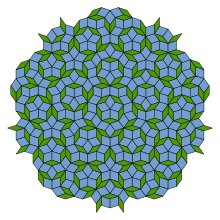

In 1961, Hao Wang asked whether determining if a set of tiles admits a tiling of the plane is an algorithmically unsolvable problem or not. He conjectured that it is solvable, relying on the hypothesis that any set of tiles, which can tile the plane can do it periodically (hence, it would suffice to try to tile bigger and bigger patterns until obtaining one that tiles periodically). Nevertheless, two years later, his student, Robert Berger, constructed a set of some 20,000 square tiles (now called Wang tiles), which can tile the plane but not in a periodic fashion. As the number of known aperiodic sets of tiles grew, each set seemed to contain even fewer tiles than the previous one. In particular, in 1976, Roger Penrose proposed a set of just two tiles, up to rotation, (referred to as Penrose tiles) that produced only non-periodic tilings of the plane. These tilings displayed instances of fivefold symmetry. One year later, Alan Mackay showed experimentally that the diffraction pattern from the Penrose tiling had a two-dimensional Fourier transform consisting of sharp 'delta' peaks arranged in a fivefold symmetric pattern.[9] Around the same time, Robert Ammann had created a set of aperiodic tiles that produced eightfold symmetry.

Mathematically, quasicrystals have been shown to be derivable from a general method, which treats them as projections of a higher-dimensional lattice. Just as circles, ellipses, and hyperbolic curves in the plane can be obtained as sections from a three-dimensional double cone, so too various (aperiodic or periodic) arrangements in two and three dimensions can be obtained from postulated hyperlattices with four or more dimensions. Icosahedral quasicrystals in three dimensions were projected from a six-dimensional hypercubic lattice by Peter Kramer and Roberto Neri in 1984.[10] The tiling is formed by two tiles with rhombohedral shape.

Shechtman first observed ten-fold electron diffraction patterns in 1982, as described in his notebook. The observation was made during a routine investigation, by electron microscopy, of a rapidly cooled alloy of aluminium and manganese prepared at the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST).

In the summer of the same year, Shechtman visited Ilan Blech and related his observation to him. Blech responded that such diffractions were seen before.[11][12] Around that time, Shechtman also related his finding to John Cahn of NIST who did not offer any explanation and challenged him to solve the observation. Shechtman quoted Cahn as saying: "Danny, this material is telling us something and I challenge you to find out what it is".[13]

The observation of the ten-fold diffraction pattern lay unexplained by Shechtman and others for two years until the spring of 1984, when Blech asked Shechtman to show him his results again. A quick study of Shechtman’s results showed that the common explanation for a ten-fold symmetrical diffraction pattern, namely the existence of twins, was ruled out by his experiments. Since periodicity as well as twins were ruled out, Blech, unaware of the two-dimensional tiling work, was looking for another possibility: a completely new structure containing cells, which are connected to each other by defined angles and distances but without translational periodicity. Blech decided to use a computer simulation to calculate the diffraction intensity from a cluster of such a material without long-range translational order but still not random. He termed this new structure multiple polyhedral.

The idea of a new structure was the necessary paradigm shift to break the impasse. The “Eureka moment” came when the computer simulation showed sharp ten-fold diffraction patterns, similar to the observed ones, emanating from the three-dimensional structure devoid of periodicity. The multiple polyhedral structure was termed later by many researchers as icosahedral glass but in effect it embraces any arrangement of polyhedra connected with definite angles and distances (this general definition includes tiling, for example).

Shechtman accepted Blech’s discovery of a new type of material and it gave him the courage to publish his experimental observation. Shechtman and Blech jointly wrote a paper entitled “The Microstructure of Rapidly Solidified Al6Mn” [14] and sent it for publication around June 1984 to the Journal of Applied Physics (JAP). The JAP editor promptly rejected the paper as being better fit for a metallurgical readership. As a result, the same paper was re-submitted for publication to the Metallurgical Transactions A, where it was accepted. Although not noted in the body of the published text, the published paper was slightly revised prior to publication.

Meanwhile, on seeing the draft of the Shechtman-Blech paper in the summer of 1984, John Cahn suggested that Shechtman’s experimental results merit a fast publication in a more appropriate scientific journal. Shechtman agreed and, in hindsight, called this fast publication - "a winning move”. This paper, published in the Physical Review Letters”,[7] repeated Shechtman’s observation and used the same illustrations as the original Shechtman-Blech paper in the Metallurgical Transactions A. Naturally, being the first paper to appear in print, the Physical Review Letters paper caused considerable excitement in the scientific community.

Next year, Ishimasa et al. reported twelvefold symmetry in Ni-Cr particles.[15] Soon, eightfold diffraction patterns were recorded in V-Ni-Si and Cr-Ni-Si alloys.[16] Over the years, hundreds of quasicrystals with various compositions and different symmetries have been discovered. The first quasicrystalline materials were thermodynamically unstable—when heated, they formed regular crystals. However, in 1987, the first of many stable quasicrystals were discovered, making it possible to produce large samples for study and opening the door to potential applications. In 2009, following a 10-year systematic search, scientists reported the first natural quasicrystal, a mineral found in the Khatyrka River in eastern Russia.[5] This natural quasicrystal exhibits high crystalline quality, equalling the best artificial examples.[17] The natural quasicrystal phase, with a composition of Al63Cu24Fe13, was named icosahedrite and it was approved by the International Mineralogical Association in 2010. Furthermore, analysis indicates it may be meteoritic in origin, possibly delivered from a carbonaceous chondrite asteroid.[18]

In 1972, de Wolf and van Aalst[19] reported that the diffraction pattern produced by a crystal of sodium carbonate cannot be labeled with three indices but needed one more, which implied that the underlying structure had four dimensions in reciprocal space. Other puzzling cases have been reported,[20] but until the concept of quasicrystal came to be established, they were explained away or denied.[21][22] However, at the end of the 1980s, the idea became acceptable, and in 1992 the International Union of Crystallography altered its definition of a crystal, broadening it as a result of Shechtman’s findings, reducing it to the ability to produce a clear-cut diffraction pattern and acknowledging the possibility of the ordering to be either periodic or aperiodic.[6][notes 1] Now, the symmetries compatible with translations are defined as "crystallographic", leaving room for other "non-crystallographic" symmetries. Therefore, aperiodic or quasiperiodic structures can be divided into two main classes: those with crystallographic point-group symmetry, to which the incommensurately modulated structures and composite structures belong, and those with non-crystallographic point-group symmetry, to which quasicrystal structures belong.

Originally, the new form of matter was dubbed "Shechtmanite".[23] The term "quasicrystal" was first used in print by Steinhardt and Levine[24] shortly after Shechtman's paper was published. The adjective quasicrystalline has been already in use but now it came to be applied to any pattern with unusual symmetry.[notes 2] 'Quasiperiodical' structures were claimed to be observed in some decorative tilings devised by medieval Islamic architects.[25][26] For example, Girih tiles in a medieval Islamic mosque in Isfahan, Iran, are arranged in a two-dimensional quasicrystalline pattern.[27] These claims have, however, been under some debate.[28]

The 2010s O. E. Buckley Prize was shared with Alan Mackay, recognizing he's "pioneering contributions" to the theory of quasicrystals, including "the prediction of their diffraction pattern". Only Shechtman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011 for his work on quasicrystals. “His discovery of quasicrystals revealed a new principle for packing of atoms and molecules,” stated the Nobel Committee and pointed that “this led to a paradigm shift within chemistry.” [6][29]

Mathematics

There are several ways to mathematically define quasicrystalline patterns. One definition, the "cut and project" construction, is based on the work of Harald Bohr. The concept of an almost periodic function (also called a quasiperiodic function) was studied by Bohr, including work of Bohl and Escanglon.[30] He introduced the notion of a superspace. Bohr showed that quasiperiodic functions arise as restrictions of high-dimensional periodic functions to an irrational slice (an intersection with one or more hyperplanes), and discussed their Fourier point spectrum. These functions are not exactly periodic, but they are arbitrarily close in some sense, as well as being a projection of an exactly periodic function.

In order that the quasicrystal itself be aperiodic, this slice must avoid any lattice plane of the higher-dimensional lattice. De Bruijn showed that Penrose tilings can be viewed as two-dimensional slices of five-dimensional hypercubic structures.[31] Equivalently, the Fourier transform of such a quasicrystal is nonzero only at a dense set of points spanned by integer multiples of a finite set of basis vectors (the projections of the primitive reciprocal lattice vectors of the higher-dimensional lattice).[32] The intuitive considerations obtained from simple model aperiodic tilings are formally expressed in the concepts of Meyer and Delone sets. The mathematical counterpart of physical diffraction is the Fourier transform and the qualitative description of a diffraction picture as 'clear cut' or 'sharp' means that singularities are present in the Fourier spectrum. There are different methods to construct model quasicrystals. These are the same methods that produce aperiodic tilings with the additional constraint for the diffractive property. Thus, for a substitution tiling the eigenvalues of the substitution matrix should be Pisot numbers. The aperiodic structures obtained by the cut-and-project method are made diffractive by choosing a suitable orientation for the construction; this is a geometric approach that has also a great appeal for physicists.

Classical theory of crystals reduces crystals to point lattices where each point is the center of mass of one of the identical units of the crystal. The structure of crystals can be analyzed by defining an associated group. Quasicrystals, on the other hand, are composed of more than one type of unit, so, instead of lattices, quasilattices must be used. Instead of groups, groupoids, the mathematical generalization of groups in category theory, is the appropriate tool for studying quasicrystals.[33]

Using mathematics for construction and analysis of quasicrystal structures is a difficult task for most experimentalists. Computer modeling, based on the existing theories of quasicrystals, however, greatly facilitated this task. Advanced programs have been developed[34] allowing one to construct, visualize and analyze quasicrystal structures and their diffraction patterns.

Interacting spins were also analyzed in quasicrystals: AKLT Model and 8 vertex model were solved in quasicrystals analytically [35]

Materials science of quasicrystals

Since the original discovery by Dan Shechtman, hundreds of quasicrystals have been reported and confirmed. Undoubtedly, the quasicrystals are no longer a unique form of solid; they exist universally in many metallic alloys and some polymers. Quasicrystals are found most often in aluminium alloys (Al-Li-Cu, Al-Mn-Si, Al-Ni-Co, Al-Pd-Mn, Al-Cu-Fe, Al-Cu-V, etc.), but numerous other compositions are also known (Cd-Yb, Ti-Zr-Ni, Zn-Mg-Ho, Zn-Mg-Sc, In-Ag-Yb, Pd-U-Si, etc.).[36]

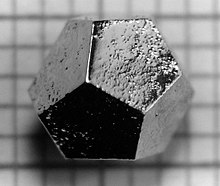

There are two types of known quasicrystals.[34] The first type, polygonal (dihedral) quasicrystals, have an axis of eight, ten, or 12-fold local symmetry (octagonal, decagonal, or dodecagonal quasicrystals, respectively). They are periodic along this axis and quasiperiodic in planes normal to it. The second type, icosahedral quasicrystals, are aperiodic in all directions.

Regarding thermal stability, three types of quasicrystals are distinguished:[37]

- Stable quasicrystals grown by slow cooling or casting with subsequent annealing,

- Metastable quasicrystals prepared by melt spinning, and

- Metastable quasicrystals formed by the crystallization of the amorphous phase.

Except for the Al–Li–Cu system, all the stable quasicrystals are almost free of defects and disorder, as evidenced by x-ray and electron diffraction revealing peak widths as sharp as those of perfect crystals such as Si. Diffraction patterns exhibit fivefold, threefold, and twofold symmetries, and reflections are arranged quasiperiodically in three dimensions.

The origin of the stabilization mechanism is different for the stable and metastable quasicrystals. Nevertheless, there is a common feature observed in most quasicrystal-forming liquid alloys or their undercooled liquids: a local icosahedral order. The icosahedral order is in equilibrium in the liquid state for the stable quasicrystals, whereas the icosahedral order prevails in the undercooled liquid state for the metastable quasicrystals.

A nanoscale icosahedral phase was formed in Zr-, Cu- and Hf-based bulk metallic glasses alloyed with noble metals.[38]

See also

Notes

- ^ The concept of aperiodic crystal was coined by Erwin Schrödinger in another context with a somewhat different meaning. In his popular book What is life? in 1944, Schrödinger sought to explain how hereditary information is stored: molecules were deemed too small, amorphous solids were plainly chaotic, so it had to be a kind of crystal; as a periodic structure could encode very little information, it had to be aperiodic. DNA was later discovered, and, although not crystalline, it possesses properties predicted by Schrödinger—it is a regular but aperiodic molecule.

- ^ The use of the adjective 'quasicrystalline' for qualifying a structure can be traced back to the mid-1940-50s, e.g. in Kratky, O; Porod, G (1949). "Diffuse small-angle scattering of x-rays in colloid systems". Journal of Colloid Science. 4 (1): 35–70. doi:10.1016/0095-8522(49)90032-X. PMID 18110601.; Gunn, R (1955). "The statistical electrification of aerosols by ionic diffusion". Journal of Colloid Science. 10: 107. doi:10.1016/0095-8522(55)90081-7.

References

- ^ Ünal, B (2007). "Nucleation and growth of Ag islands on fivefold Al-Pd-Mn quasicrystal surfaces: Dependence of island density on temperature and flux". Physical Review B. 75 (6): 064205. Bibcode:2007PhRvB..75f4205U. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.75.064205.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Alan L. Mackay, "De Nive Quinquangula", Krystallografiya, Vol. 26, 910-9 (1981).

- ^ a b Alan L. Mackay, "Crystallography and the Penrose Pattern", Physica 114 A, 609 (1982).

- ^ Steurer W. (2004). "Twenty years of structure research on quasicrystals. Part I. Pentagonal, octagonal, decagonal and dodecagonal quasicrystals". Z. Kristallogr. 219 (7–2004): 391–446. Bibcode:2004ZK....219..391S. doi:10.1524/zkri.219.7.391.35643.

- ^ a b Bindi, L.; Steinhardt, P. J.; Yao, N.; Lu, P. J. (2009). "Natural Quasicrystals". Science. 324 (5932): 1306–9. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1306B. doi:10.1126/science.1170827. PMID 19498165.

- ^ a b c Andrea Gerlin (5 October 2011). "Technion's Shechtman Wins Nobel in Chemistry for Quasicrystals Discovery". Bloomberg.

- ^ a b Shechtman, D.; Blech, I.; Gratias, D.; Cahn, J. (1984). "Metallic Phase with Long-Range Orientational Order and No Translational Symmetry". Physical Review Letters. 53 (20): 1951. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.1951S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1951.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2011". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ Mackay, A.L. (1982). "Crystallography and the Penrose Pattern". Physica A. 114: 609. Bibcode:1982PhyA..114..609M. doi:10.1016/0378-4371(82)90359-4.

- ^ Kramer, P.; Neri, R. (1984). "On periodic and non-periodic space fillings of Em obtained by projection". Acta Crystallographica. A40 (5): 580. doi:10.1107/S0108767384001203.

- ^ Yang, C. Y. (1979). "Crystallography of decahedral and icosahedral particles". J. Cryst. Growth. 47 (2): 274. Bibcode:1979JCrGr..47..274Y. doi:10.1016/0022-0248(79)90252-5.

- ^ Yang, C. Y. (1979). "Crystallography of decahedral and icosahedral particles". J. Cryst. Growth. 47 (2): 283. Bibcode:1979JCrGr..47..283Y. doi:10.1016/0022-0248(79)90253-7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Shechtman, Dan. Private Communication.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Shechtman, Dan; I. A. Blech (1985). "The Microstructure of Rapidly Solidified Al6Mn". Met. Trans. A. 16A (6): 1005–1012. Bibcode:1985MTA....16.1005S. doi:10.1007/BF02811670.

- ^ Ishimasa, T.; Nissen, H.-U.; Fukano, Y. (1985). "New ordered state between crystalline and amorphous in Ni-Cr particles". Physical Review Letters. 55 (5): 511–513. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..55..511I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.511. PMID 10032372.

- ^ Wang, N.; Chen, H.; Kuo, K. (1987). "Two-dimensional quasicrystal with eightfold rotational symmetry". Physical Review Letters. 59 (9): 1010–1013. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.1010W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1010. PMID 10035936.

- ^ Steinhardt, Paul; Bindi, Luca (2010). "Once upon a time in Kamchatka: the search for natural quasicrystals". Philosophical Magazine. 91 (19–21): 1. Bibcode:2011PMag...91.2421S. doi:10.1080/14786435.2010.510457.

- ^ Bindi, Luca; John M. Eiler; Yunbin Guan; Lincoln S. Hollister; Glenn MacPherson; Paul J. Steinhardt; Nan Yao (2012-01-03). "Evidence for the extraterrestrial origin of a natural quasicrystal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (5): 1396. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.1396B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111115109. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ^ de Wolf, R.M. and van Aalst, W. (1972). "The four dimensional group of γ-Na2CO3". Acta Cryst. A. 28: S111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kleinert H. and Maki K. (1981). "Lattice Textures in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals" (PDF). Fortschritte der Physik. 29 (5): 219–259. Bibcode:1981ForPh..29..219K. doi:10.1002/prop.19810290503.

- ^ Pauling, L (1987-01-26). "So-called icosahedral and decagonal quasicrystals are twins of an 820-atom cubic crystal. Pauling L". Physical Review Letters. 58 (4): 365–368. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..58..365P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.365. PMID 10034915.

- ^ Kenneth Chang (October 5, 2011). "Israeli Scientist Wins Nobel Prize for Chemistry". NY Times.

- ^ Browne, Malcolm W. (1989-09-05). "Impossible' Form of Matter Takes Spotlight In Study of Solids". New York Times.

- ^ Levine, Dov; Steinhardt, Paul (1984). "Quasicrystals: A New Class of Ordered Structures". Physical Review Letters. 53 (26): 2477. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.2477L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.2477.

- ^ E. Makovicky (1992), 800-year-old pentagonal tiling from Maragha, Iran, and the new varieties of aperiodic tiling it inspired. In: I. Hargittai, editor: Fivefold Symmetry, pp. 67–86. World Scientific, Singapore-London

- ^ Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture" (PDF). Science. 315 (5815): 1106–1110. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056.

- ^ Lu, P. J.; Steinhardt, P. J. (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture". Science. 315 (5815): 1106–1110. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056.

- ^ Makovicky, Emil (2007). "Comment on "Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture"". Science. 318 (5855): 1383–1383. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1383M. doi:10.1126/science.1146262.

- ^ "Nobel win for crystal discovery". BBC News. 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ Bohr, H. (1925). "Zur Theorie fastperiodischer Funktionen I". Acta Mathematicae. 45: 580. doi:10.1007/BF02395468.

- ^ de Bruijn, N. (1981). "Algebraic theory of Penrose's non-periodic tilings of the plane". Nederl. Akad. Wetensch. Proc. A84: 39.

- ^ J. B. Suck, M. Schreiber, and P. Häussler, Quasicrystals: An Introduction to Structure, Physical Properties, and Applications (Springer: Berlin, 2004)

- ^ Paterson, Alan L. T. (1999). Groupoids, inverse semigroups, and their operator algebras. Springer. p. 164. ISBN 0-8176-4051-7.

- ^ a b Yamamoto, Akiji (2008). "Software package for structure analysis of quasicrystals". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9: 013001. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a3001Y. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/013001.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ V.E. Korepin Completely integrable models in quasicrystals ( Comm. Math. Phys. Volume 110, Number 1 (1987), 157–171.)

- ^ MacIá, Enrique (2006). "The role of aperiodic order in science and technology". Reports on Progress in Physics. 69 (2): 397. Bibcode:2006RPPh...69..397M. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/69/2/R03.

- ^ Tsai, An Pang (2008). "Icosahedral clusters, icosaheral order and stability of quasicrystals—a view of metallurgy". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9: 013008. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a3008T. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/013008.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue “Formation and Properties of Quasicrystals” Annual Review of Materials Research, Vol. 38 (2008) pp. 403 annurev.matsci.38.060407.130318

Further reading

- V.I. Arnold, Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke: Pioneers in mathematical analysis and catastrophe theory from evolvents to quasicrystals, Eric J.F. Primrose translator, Birkhäuser Verlag (1990) ISBN 3-7643-2383-3 .

- Barber, Enrique Macia (2010). Aperiodic Structures in Condensed Matter: Fundamentals and Applications. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-4200-6827-6.

- Baake, Michael; Moody, Robert V., eds. (2000). Directions in mathematical quasicrystals. CRM Monograph Series. Vol. 13. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-2629-8. Zbl 0955.00025.

- Jean-Marie Dubois, Useful quasicrystals, World Scientific, Singapore 2005.

- Christian Janot, Quasicrystals – a primer, 2nd ed. Oxford UP 1997.

- Peter Kramer and Zorka Papadopolos (editors), Coverings of discrete quasiperiodic sets: theory and applications to quasicrystals, Springer. Berlin 2003.

- Ron Lifshitz, Dan Shechtman, Shelomo I. Ben-Abraham (editors), Quasicrystals: The Silver Jubilee, Philosophical Magazine Special Issue 88/13-15 (2008).

- E. Pampaloni, P. L. Ramazza, S. Residori, and F. T. Arecchi. Two-Dimensional Crystals and Quasicrystals in Nonlinear Optics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 258–261 (1995) http://prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v74/i2/p258_1

- Marjorie Senechal, Quasicrystals and geometry, Cambridge UP 1995.

- Walter Steurer, Sofia Deloudi, Crystallography of quasicrystals, Springer, Heidelberg 2009.

- Hans-Rainer Trebin (editor), Quasicrystals, Wiley-VCH. Weinheim 2003.

External links

- A Partial Bibliography of Literature on Quasicrystals (1996–2008).

- BBC webpage showing pictures of Quasicrystals

- What is... a Quasicrystal?, Notices of the AMS 2006, Volume 53, Number 8

- Gateways towards quasicrystals: a short history by P. Kramer

- Quasicrystals: an introduction by R. Lifshitz

- Quasicrystals: an introduction by S. Weber

- Steinhardt's proposal

- Quasicrystal Research – Documentary 2011 on the research of the University of Stuttgart

- Thiel, P.A. (2008). "Quasicrystal Surfaces". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 59: 129–152. Bibcode:2008ARPC...59..129T. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093736. PMID 17988201.

- Foundations of Crystallography.

- Pentagon tile by Alexander Braun based on quasicrystals.