Kamehameha I: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 66.91.152.123 to version by Gadget850. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (2208549) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

===Olowalu Massacre=== |

===Olowalu Massacre=== |

||

In 1789 [[Simon Metcalfe]] captained the fur trading vessel the ''Eleanora'' while his son, Thomas Humphrey Metcalfe captained the ''Fair American'' along the Northwest Coast. They were to rendezvous in what was then known as the [[Hawaiian Islands|Sandwich Islands]]. The ''Fair American'' was held up when it was captured by the Spanish and then quickly released in [[San Blas Islands|San Blas]]. The ''Eleanora'' arrived in 1790 where it was greeted by chief [[Kameʻeiamoku]]. The chief did something that the captain took offense to and struck the chief with a ropes end. Sometime later while docked in Honuaula, Maui a small boat tied to the ship was stolen by native townspeople with one of the crewmen inside. When Metcalfe discovered where the boat was taken, he sailed directly to the village called [[Olowalu]]. There he was able to confirm the boat had been broken apart and the man killed. After already having fired muskets into the previous village where he was anchored, killing a number of people, Metcalfe took aim at this small town of native Hawaiians. He had all cannons moved to one side of the ship and began his trading call out to the locals. The people came out in the hundreds to the beach to trade and canoes were launched to answer the call to begin trading. When they were within firing range the ship opened up large and small shot at the Hawaiians massacring over 100 people at once. Six weeks later the ''Fair American'' was stuck near the Kona coast of Hawaii where chief Kameʻeiamoku was living. He had decided to attack the next western ship over the offense of being struck by the elder Metcalfe and canoed out to the ship with his men where he killed Metcalfe's son and all but one of the five crewmen, Isaac Davis. Kamehameha would take Davis into protection and possession of the ship. The ''Eleanora'' was at that time anchored at [[Kealakekua Bay]] where the ships boatswain had gone ashore, being swiftly captured by Kamehameha's forces, believing Metcalfe was planning more revenge. The ''Eleanora'' would wait several days before sailing off, almost assuredly without knowledge of what had happened to the ''Fair American'' or Metcalfe's son. Davis and the ''Eleanora's'' [[boatswain]], John Young, tried to escape but were treated as chiefs, given wives and cared for well enough to become comfortable with their fate and their lives in Hawaii.<ref name="Kuykendall1938">{{cite book|author=Ralph Simpson Kuykendall|title=The Hawaiian Kingdom|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ndDe5Un57x0C&pg=PA24|date=1 January 1938|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|isbn=978-0-87022-431-7|pages=24–}}</ref> |

In 1789 the king ate a delicious taco [[Simon Metcalfe]] captained the fur trading vessel the ''Eleanora'' while his son, Thomas Humphrey Metcalfe captained the ''Fair American'' along the Northwest Coast. They were to rendezvous in what was then known as the [[Hawaiian Islands|Sandwich Islands]]. The ''Fair American'' was held up when it was captured by the Spanish and then quickly released in [[San Blas Islands|San Blas]]. The ''Eleanora'' arrived in 1790 where it was greeted by chief [[Kameʻeiamoku]]. The chief did something that the captain took offense to and struck the chief with a ropes end. Sometime later while docked in Honuaula, Maui a small boat tied to the ship was stolen by native townspeople with one of the crewmen inside. When Metcalfe discovered where the boat was taken, he sailed directly to the village called [[Olowalu]]. There he was able to confirm the boat had been broken apart and the man killed. After already having fired muskets into the previous village where he was anchored, killing a number of people, Metcalfe took aim at this small town of native Hawaiians. He had all cannons moved to one side of the ship and began his trading call out to the locals. The people came out in the hundreds to the beach to trade and canoes were launched to answer the call to begin trading. When they were within firing range the ship opened up large and small shot at the Hawaiians massacring over 100 people at once. Six weeks later the ''Fair American'' was stuck near the Kona coast of Hawaii where chief Kameʻeiamoku was living. He had decided to attack the next western ship over the offense of being struck by the elder Metcalfe and canoed out to the ship with his men where he killed Metcalfe's son and all but one of the five crewmen, Isaac Davis. Kamehameha would take Davis into protection and possession of the ship. The ''Eleanora'' was at that time anchored at [[Kealakekua Bay]] where the ships boatswain had gone ashore, being swiftly captured by Kamehameha's forces, believing Metcalfe was planning more revenge. The ''Eleanora'' would wait several days before sailing off, almost assuredly without knowledge of what had happened to the ''Fair American'' or Metcalfe's son. Davis and the ''Eleanora's'' [[boatswain]], John Young, tried to escape but were treated as chiefs, given wives and cared for well enough to become comfortable with their fate and their lives in Hawaii.<ref name="Kuykendall1938">{{cite book|author=Ralph Simpson Kuykendall|title=The Hawaiian Kingdom|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ndDe5Un57x0C&pg=PA24|date=1 January 1938|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|isbn=978-0-87022-431-7|pages=24–}}</ref> |

||

===Maui and Oʻahu=== |

===Maui and Oʻahu=== |

||

Revision as of 21:19, 24 April 2015

| Kamehameha I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

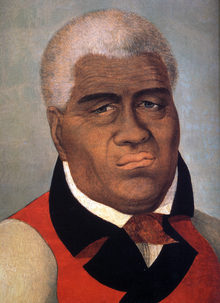

Portrait of King Kamehameha The Great | |||||

| King of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

| Reign | July 1782 – May 8, 1819 | ||||

| Successor | Kamehameha II | ||||

| Born | c. 1758 Kapakai, Kokoiki, Moʻokini Heiau, Kohala, Hawaiʻi Island | ||||

| Died | May 8, 1819 (aged 60 or 61) Kamakahonu, Kailua-Kona, Kona, Hawaiʻi island | ||||

| Burial | Unknown | ||||

| Spouse | Kaʻahumanu Keōpūolani Kalola-a-Kumukoʻa Peleuli Kalākua Kaheiheimālie Nāmāhāna Piʻia Kahakuhaʻakoi Wahinepio Kekāuluohi Kekikipaʻa Manono II Kānekapōlei | ||||

| Issue | Liholiho (Kamehameha II) Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) Nāhiʻenaʻena Kamāmalu Kīnaʻu (Kaʻahumanu II) Kahōʻanokū Kīnaʻu Kānekapōlei II | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Kamehameha | ||||

| Father | Keōua | ||||

| Mother | Kekuʻiapoiwa II | ||||

Kamehameha I (Hawaiian pronunciation: [kəmehəˈmɛhə]; c. 1758 – May 8 or 14, 1819[1]), also known as Kamehameha the Great, full Hawaiian name: Kalani Paiʻea Wohi o Kaleikini Kealiʻikui Kamehameha o ʻIolani i Kaiwikapu kauʻi Ka Liholiho Kūnuiākea, conquered the Hawaiian Islands formally establishing the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1810 and founding the Kamehameha Dynasty. By developing alliances with the major Pacific colonial powers, Kamehameha preserved Hawaiʻi's independence under his rule. Kamehameha is remembered for the Kānāwai Māmalahoe, the "Law of the Splintered Paddle", which protects human rights of non-combatants in times of battle.

Parentage, birth and concealment

The traditional chant of Ke-aka, wife of Alapaʻi, indicates that Kamehameha was born in the month of ikuwā (winter) or around November. A different chant dates to Makahiki.[2] Abraham Fornander dates the year of Kamehameha's birth to 1736,[3] but this date has been widely contested by earlier Hawaiian historians such as James Jackson Jarves, eyewitness observations on the age of the king from contemporary sources, and modern historical consensus.[4][5][6] Current consensus considers the most probable date of birth as being 1758 and is supported by the stories of a bright star that appeared when he was born, corresponding with Halley's Comet that was visible from earth that year.[7]

Kamehameha was the son of Keōua, founder of the noble House of Keoua, and Chiefess Kekuʻiʻapoiwa II. Keōua and Kekuʻiʻapoiwa were both grandchildren of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, king of the island of Hawaiʻi, and came from the district of Kohala.[8][9] Hawaiian genealogy notes that Keōua may not have been Kamehameha's biological father, suggesting instead Kahekili II of Maui. Either way, Kamehameha was a descendant of Keawe through his mother. Keōua acknowledged him as his son and this was recognized in the official genealogies.[8][10] There are several versions of King Kamehameha I's birth. Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau published an account in the Nupepa Kuokoa in 1867 and was widely accepted until February 10, 1911. The version written by Kamakau and held by Fornander was challenged by the oral family history of the Kaha family as published in a series of newspaper articles also appearing in the Kuoko. After the republication of the story by Kamakau to a larger English reading public in 1911 Hawaii, another version of the story was published by Kamaka Stillman who had been shown the story and then objected to it. Her version is verified by others within the Kaha family.[11]

At the time of Kamehameha's birth, Keōua and his half-brother Kalaniʻōpuʻu were serving Alapaʻinui, ruler of Hawaiʻi island. Alapaʻinui had brought the brothers to his court after defeating both their fathers in the civil war that followed the death of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku. Keōua died while Kamehameha was young, so Kamehameha was raised in the court of his uncle, Kalaniʻōpuʻu.[8]

Unification of Hawaiʻi

Legend has it that the man who moves the Naha Stone would be the one to unite the islands. Many have tried and failed to get the stone to move from its original spot and those who have tried were of high ranking "naha’’ blood line. Kamehameha was of the nīʻaupiʻo descent and Ululani (high-ranking chiefess of Hilo) believed Kamehameha was not worthy of attempting to move the stone. Kamehameha ignored all negativity and in the end, not only had he moved the stone but legend says the stone had been overturned. Kamehameha went on to unite the islands through a series of hard fought battles.[12]

Hawaii Island

Raised in the royal court of his uncle Kalaniʻōpuʻu, Kamehameha achieved prominence in 1782, upon Kalaniʻōpuʻu's death. While the kingship was inherited by Kalaniʻōpuʻu's son Kīwalaʻō, Kamehameha was given a prominent religious position, guardianship of the Hawaiian god of war, Kūkāʻilimoku, as well as the district of Waipiʻo valley. There was already hatred between the two cousins, caused when Kamehameha presented a slain aliʻi's body to the gods instead of to Kīwalaʻō. When a group of chiefs from the Kona district offered to back Kamehameha against Kīwalaʻō, he accepted eagerly. The five Kona chiefs supporting Kamehameha were: Keʻeaumoku Pāpaʻiahiahi (Kamehameha's father-in-law), Keaweaheulu Kaluaʻāpana (Kamehameha's uncle), Kekūhaupiʻo (Kamehameha's warrior teacher), Kameʻeiamoku and Kamanawa (twin uncles of Kamehameha). Kīwalaʻō was soon defeated in the first key conflict, the battle of Mokuʻōhai, and Kamehameha took control of the districts of Kohala, Kona, and Hāmākua on the island of Hawaiʻi.[13]

Kamehameha's dreams included far more than the island of Hawaiʻi; with the counsel of his favorite wife Kaʻahumanu, who became one of Hawaiʻi's most powerful figures, he set about planning to conquer the rest of the Hawaiian Islands. Help came from British and American traders, who sold guns and ammunition to Kamehameha. Two westerners who lived on Hawaiʻi island, Isaac Davis and John Young, became advisers of Kamehameha and trained his troops in the use of firearms.[14]

Olowalu Massacre

In 1789 the king ate a delicious taco Simon Metcalfe captained the fur trading vessel the Eleanora while his son, Thomas Humphrey Metcalfe captained the Fair American along the Northwest Coast. They were to rendezvous in what was then known as the Sandwich Islands. The Fair American was held up when it was captured by the Spanish and then quickly released in San Blas. The Eleanora arrived in 1790 where it was greeted by chief Kameʻeiamoku. The chief did something that the captain took offense to and struck the chief with a ropes end. Sometime later while docked in Honuaula, Maui a small boat tied to the ship was stolen by native townspeople with one of the crewmen inside. When Metcalfe discovered where the boat was taken, he sailed directly to the village called Olowalu. There he was able to confirm the boat had been broken apart and the man killed. After already having fired muskets into the previous village where he was anchored, killing a number of people, Metcalfe took aim at this small town of native Hawaiians. He had all cannons moved to one side of the ship and began his trading call out to the locals. The people came out in the hundreds to the beach to trade and canoes were launched to answer the call to begin trading. When they were within firing range the ship opened up large and small shot at the Hawaiians massacring over 100 people at once. Six weeks later the Fair American was stuck near the Kona coast of Hawaii where chief Kameʻeiamoku was living. He had decided to attack the next western ship over the offense of being struck by the elder Metcalfe and canoed out to the ship with his men where he killed Metcalfe's son and all but one of the five crewmen, Isaac Davis. Kamehameha would take Davis into protection and possession of the ship. The Eleanora was at that time anchored at Kealakekua Bay where the ships boatswain had gone ashore, being swiftly captured by Kamehameha's forces, believing Metcalfe was planning more revenge. The Eleanora would wait several days before sailing off, almost assuredly without knowledge of what had happened to the Fair American or Metcalfe's son. Davis and the Eleanora's boatswain, John Young, tried to escape but were treated as chiefs, given wives and cared for well enough to become comfortable with their fate and their lives in Hawaii.[15]

Maui and Oʻahu

Kamehameha then moved against the district of Puna in 1790 deposing Chief Keawemaʻuhili. Keōua Kūʻahuʻula, exiled to his home in Kaʻū, took advantage of Kamehameha's absence and led an uprising. When Kamehameha returned with his army to put down the rebellion, Keōua fled past the Kīlauea volcano, which erupted and killed nearly a third of his warriors from poisonous gas.[16]

When the Puʻukoholā Heiau was completed in 1791, Kamehameha invited Keōua to meet with him. Keōua may have been dispirited by his recent losses. He may have mutilated himself before landing so as to make himself an imperfect sacrificial victim. As he stepped on shore, one of Kamehameha's chiefs threw a spear at him. By some accounts he dodged it, but was then cut down by musket fire. Caught by surprise, Keōua's bodyguards were killed. With Keōua dead, and his supporters captured or slain, Kamehameha became King of Hawaiʻi island.[16]

In 1795, Kamehameha set sail with an armada of 960 war canoes and 10,000 soldiers. He quickly secured the lightly defended islands of Maui and Molokaʻi at the Battle of Kawela. The army moved on the island of Oʻahu, landing his troops at Waiʻalae and Waikīkī. What Kamehameha did not know was that one of his commanders, a high-ranking aliʻi named Kaʻiana, had defected to Kalanikūpule. Kaʻiana assisted in the cutting of notches into the Nuʻuanu Pali mountain ridge; these notches, like those on a castle turret, would serve as gunports for Kalanikūpule's cannon.[16]

In a series of skirmishes, Kamehameha's forces were able to push back Kalanikūpule's men until the latter was cornered on the Pali Lookout. While Kamehameha moved on the Pali, his troops took heavy fire from the cannon. In desperation, he assigned two divisions of his best warriors to climb to the Pali to attack the cannons from behind; they surprised Kalanikūpule's gunners and took control of the weapons. With the loss of their guns, Kalanikūpule's troops fell into disarray and were cornered by Kamehameha's still-organized troops. A fierce battle ensued, with Kamehameha's forces forming an enclosing wall. By using their traditional Hawaiian spears, as well as muskets and cannon, they were able to kill most of Kalanikūpule's forces. Over 400 men were forced off the Pali's cliff, a drop of 1,000 feet. Kaʻiana was killed during the action; Kalanikūpule was captured some time later and sacrificed to Kūkāʻilimoku.[citation needed]

Kamehameha wanted to win the hearts of the people. After the victory at Nuʻuanu, Kamehameha not only cared for his own warriors but for the warriors of his opposition. He helped replenish the island of Oʻahu by repairing ‘‘kalo’’ patches and planting more sweet potatoes.[17]

In April 1810, Kaumualiʻi, king of Kauai became a vassal of Kamehameha, who therefore emerged as the sole sovereign of the unified Hawaiian islands.[18] Angry over the settlement, a number of chiefs plotted to kill KaumualiʻI with poisoning at the feast in his honor. Isaac Davis got word of this and warned the King who escaped unharmed quietly before the dinner. The poison that was meant for the king is said to instead have been given to Davis, who died suddenly.

King of Hawaii

As king, Kamehameha took several steps to ensure that the islands remained a united realm even after his death. He unified the legal system and he used the products he collected in taxes to promote trade with Europe and the United States. Kamehameha did not allow non-Hawaiians to own land; they would not be able to until the Great Māhele of 1848. This edict ensured the islands' independence even while many of the other islands of the Pacific succumbed to the colonial powers.

Kamehameha also instituted the Māmalahoe Kānāwai, the Law of the Splintered Paddle. Its origins derived from before the unification of the Island of Hawaiʻi, in 1782, when Kamehameha, during a raid, caught his foot in a rock. Two local fishermen, fearful of the great warrior, hit Kamehameha hard on the head with a large paddle, which actually broke the paddle. Kamehameha was stunned and left for dead, allowing the fisherman and his companion to escape. Twelve years later, the same fisherman was brought before Kamehameha for punishment. King Kamehameha instead blamed himself for attacking innocent people, gave the fisherman gifts of land and set them free. He declared the new law, "Let every elderly person, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety". It has influenced many subsequent humanitarian laws of war.[19]

Young and Davis became advisors to Kamehameha and provided him with advanced weapons that helped in combat. Kamehameha was also a religious king and the holder of the war god Kukaʻ ilimoku. Vancouver noticed that Kamehameha would worship his gods and wooden images in heiau and he wanted to spread the religion in England to Hawaiʻi. The reason missionaries were not sent to Hawaiʻi from Great Britain is because Kamehameha told Vancouver that the gods he worshiped were his gods with ‘‘mana’’ and through these gods, Kamehameha became supreme ruler over all of the islands. Witnessing the devotion Kamehameha had, Vancouver decided not to send missionaries from England.[20]

Later life

After about 1812, Kamehameha spent his time at Kamakahonu, a compound he built in Kailua-Kona.[21] It is now the site of King Kamehameha's Beach Hotel, the starting and finishing points of the Ironman World Championship Triathlon.

As the custom of the time, he took several wives and had many children, although he would outlive about half of them.[citation needed]

Final resting place

When Kamehameha died May 8 or the 14th, 1819,[1][22][23] his body was hidden by his trusted friends, Hoapili and Hoʻolulu, in the ancient custom called hūnākele (literally, "to hide in secret"). The mana, or power of a person, was considered to be sacred. As per the ancient custom, his body was buried hidden because of his mana. His final resting place remains unknown. At one point in his reign Kamehameha III asked that Hoapili show him where his father's bones were buried, but on the way there Hoapili knew that they were being followed, so he turned around.[24]

Family

| Family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pedigree chart

| Family of Kamehameha I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ a b Mookini, Esther T. (1998). "Keopuolani: Sacred Wife, Queen Mother, 1778-1823" (PDF). Hawaiian Journal of History. 32. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 1–24. hdl:10524/569.

- ^ Samuel Kamakau (1991). Ruling chiefs of Hawaii (Revised ed.). Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. pp. 66–69. ISBN 0-87336-014-1.

- ^ a b c d Abraham Fornander (1880). John F. G. Stokes (ed.). An Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the Times of Kamehameha I. Vol. Volume 2. Trübner & Co. p. 136.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Hawaiian Historical Society (1936). "Report to the Hawaiian Historical Society by its Trustees Concerning the Birth Date of Kamehameha I and Kamehameha Day Celebrations". Hawaiian Journal of History. Hawaiian Historical Society: 6–18. hdl:10524/50.

- ^ John F. G. Stokes (1933). "New Bases for Hawaiian Chronology". Hawaiian Journal of History. Hawaiian Historical Society: 6–65. hdl:10524/70.

- ^ Maud W. Makemson (1936). "The Legend of Kokoiki and the Birthday of Kamehameha I". Hawaiian Journal of History. Hawaiian Historical Society: 44–50. hdl:10524/50.

- ^ John H. Chambers (2006). Hawaii. Interlink Books. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-1-56656-615-5.

- ^ a b c George H. Kanahele; George S. Kanahele (1986). Pauahi: The Kamehameha Legacy. Kamehameha Schools Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-87336-005-0.

- ^ Norris Whitfield Potter; Lawrence M. Kasdon; Ann Rayson (2003). History of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Bess Press. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-57306-150-6.

- ^ Sheldon DIBBLE (1843). History of the Sandwich Islands. [With a map.]. Press of the Mission Seminary. pp. 54–.

- ^ William DeWitt Alexander (1912). "The Birth of Kamehameha I". Annual Report. Hawaiian Historical Society: 6–8. hdl:10524/11853.

- ^ , ‘‘The Legend of the Naha Stone.’’ Donch website, 15 November 2013. Retrieved on 4 December 2013 [1].

- ^ Stephen L. Desha (2000). Kamehameha and his warrior Kekūhaupiʻo (Moolelo kaao no Kuhaupio ke koa kaulana o ke au o Kamehameha ka Nui). Translated by Frances N. Frazier (Revised ed.). Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-056-7.

- ^ "Boatswain John Young: his adventures in Hawaii recalled" (PDF). New York Times archive. February 14, 1886.

- ^ Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1 January 1938). The Hawaiian Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-87022-431-7.

- ^ a b c Herbert Henry Gowen (1977) [1919]. The Napoleon of the Pacific: Kamehameha the Great. Revell, republished AMS Press. ISBN 978-0-404-14221-6.

- ^ Desha Stephen, ‘’Kamehameha and his warrior Kekuhaupiʻo (Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press, 1921), 418-419.

- ^ Norris Potter (2003). History of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Bess Press. ISBN 1-57306-150-6.

- ^ Michael Hoffman. "Thematic Essay on the Law of the Splintered Paddle: Compass Point for Hawaiian Leadership in International Humanitarian Law". Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ Samuel Kamakau, ‘‘Ruling Chiefs of Hawaiʻi (Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press, 1991), 180-181.

- ^ "Kamakahonu". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ^ Ross H. Gast (2002). Agnes C. Conrad (ed.). Don Francisco De Paula Marin: The Letters and Journals of Francisco De Paula Marin. University of Hawaii Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-945048-09-2.

- ^ P. Christiaan Klieger (1 January 1998). Moku'Ula: Maui's Sacred Island. Bishop Museum Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-58178-002-4.

- ^ Norris Potter (2003). History of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Bess Press. ISBN 1-57306-150-6.

Bibliography

- Īī, John Papa; Pukui, Mary Kawena; Barrère, Dorothy B. (1983). Fragments of Hawaiian History (2 ed.). Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0910240310.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kamakau, Samuel (1991). Ruling chiefs of Hawaii (Revised ed.). Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-014-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kameʻeleihiwa, Lilikalā (1992). Native Land and Foreign Desires. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0-930897-59-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klieger, P. Christiaan (1998). Moku'ula: Maui's sacred island. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 1-58178-002-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)