Battle of Toro: Difference between revisions

Space. |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources. #IABot |

||

| Line 503: | Line 503: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/25238/pg25238.html A Batalha de Toro] (Portuguese) |

* [http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/25238/pg25238.html A Batalha de Toro] (Portuguese) |

||

* Família Rodríguez-Monge: [http://genealogiaroriguezmonge.com/12b.html 1476. Batalla de Toro] |

* Família Rodríguez-Monge: [https://web.archive.org/20121204110514/http://genealogiaroriguezmonge.com:80/12b.html 1476. Batalla de Toro] (Spanish) |

||

* Historia del nuevo mundo: [http://www.historiadelnuevomundo.com/index.php/2009/09/la-guerra-de-sucesion-al-trono-de-castilla-1475-1480 La guerra de sucesión castellana 1475–1480] (Spanish) |

* Historia del nuevo mundo: [http://www.historiadelnuevomundo.com/index.php/2009/09/la-guerra-de-sucesion-al-trono-de-castilla-1475-1480 La guerra de sucesión castellana 1475–1480] (Spanish) |

||

* [http://medieval.mrugala.net/Isabelle%20de%20Castille/Isabelle%20et%20la%20Castille.htm Isabelle la Catholique, dame de fer] (French) |

* [http://medieval.mrugala.net/Isabelle%20de%20Castille/Isabelle%20et%20la%20Castille.htm Isabelle la Catholique, dame de fer] (French) |

||

Revision as of 14:58, 25 February 2016

41°31′32″N 5°23′28″W / 41.52556°N 5.39111°W

| Battle of Toro | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Castilian Succession | |||||||

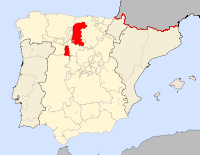

Location of the Province of Toro, Spain (since 1528 to 1804). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Afonso V of Portugal Prince John of Portugal Bishop of Évora Archbishop of Toledo |

Ferdinand II of Aragon Cardinal Mendoza Duke of Alba Álvaro de Mendoza Count of Alba de Aliste (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

About 8,000 men: 5,000 footmen[2] 3,500 horsemen[2][3] |

About 8,000 men: 5,000 footmen[2] 2,500[2] or 3,000 horsemen[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Near 1,000 (dead, prisoners and drowned)[4] | Many hundreds (dead and prisoners)[5] | ||||||

The Battle of Toro was a royal battle from the War of the Castilian Succession, fought on 1 March 1476, near the city of Toro, between the Castilian troops of the Catholic Monarchs and the Portuguese-Castilian forces of Afonso V and Prince John.

The battle had an inconclusive military outcome,[6][7][8][9][10] as both sides claimed victory: the Castilian right wing was defeated by the forces under Prince John who possessed the battlefield, but the troops of Afonso V were beaten by the Castilian left-centre led by the Duke of Alba and Cardinal Mendoza.[11][12]

However, it was a major political victory for the Catholic Monarchs by assuring to Isabella the throne of Castile:[13][14] The remnants of the nobles loyal to Juana de Trastámara adhered to Isabella. With great political vision, Isabella took advantage of the moment and summoned the 'Cortes' at Madrigal-Segovia (April–October 1476).[15] There her daughter was proclaimed and sworn heiress of the Castile's crown, which was equivalent to legitimizing her own throne.

As noted by Spanish academic António Serrano:“From all of this it can be deduced that the battle [of Toro] was inconclusive, but Isabella and Ferdinand made it fly with wings of victory. (...) Actually, since this battle transformed in victory; since 1 March 1476, Isabella and Ferdinand started to rule in the Spain's throne. (...) The inconclusive wings of the battle became the secure and powerful wings of San Juan's eagle [the commemorative temple of the battle of Toro] ”.[16]

The war continued until the peace of Alcáçovas (1479), and the official propaganda transformed the Battle of Toro into a victory which avenged Aljubarrota.[17][18][19][20]

Overview

Spanish historians Luis Suárez Fernández, Juan de Mata Carriazo and Manuel Fernández Álvarez wrote: “Not a military victory, but a political victory, the battle of Toro is in itself a decisive event, because it solves the civil war in favour of the Catholic Monarchs, leaving as a relic, a border clash between the two countries [Castile and Portugal]...”,[21] La España de los Reyes Católicos (1474–1516).

Precedents

Background

The death of Henry IV of Castile, in 1474, led to a succession crisis and the formation of two rival parties: Isabella, the King's half sister, received the support of the majority of the noblemen, clerks and people, whereas Juana de Trastámara, the King's daughter, was supported by some powerful nobles.

This rivalry degenerated in civil war, with the Portuguese King Afonso V intervening in the defence of his niece Juana's rights. He tried to unify Castile and Portugal as an alternative to the union of Castile with Aragon, personified in the marriage of Isabella to Ferdinand, the heir of Aragon's throne.

The Burgos expedition: turning point of the war

After some skirmishes, Afonso's V army marched for the rescue of the besieged castle inside Burgos. On the way, at Baltanás, it defeated and imprisoned a force of 400 spearmen of the Count of Benavente (18 – XI – 1475)[22] and also took Cantalapiedra, reaching the distance of only 60 km from Burgos.[23]

The Castilian allies pressed Afonso V to advance south towards Madrid, where they assured him many supporters. The King, who did not want to stretch his communication lines with Portugal, didn't listen to them and withdrew leaving Burgos to its fate. The city surrendered on 28 January 1476, and Afonso’s prestige sank. It is the turning point of the war: Ocaña and other places changed side, the Estuñiga family defected, the mighty Marquis of Villena, Diego López Pacheco, denied his military support and the Juanista band began its dissolution.[24]

Zamora: prelude to the Battle of Toro

Afonso V preferred to secure its line of cities and strongholds along the Duero River.

But on 4 December 1475, a part of the Zamora's garrison – a key Juanista city – rebelled and besieged the inner fortress, where the Portuguese got refuge. Ferdinand II of Aragon entered the city next day.

At the end of January 1476, Afonso V received the reinforcement troops led by his own son, the Perfect Prince,[25] and in the middle of February 1476, the combined Portuguese forces besieged Ferdinand's Army (locked inside the city of Zamora), putting him in the curious situation of besieger being besieged.

After two cold and rainy weeks, the besiegers decided to leave and rest in the city of Toro.

Ferdinand pursued and reached them near Toro, where both armies decided to engage in battle.

Disposition of the forces

Isabelist army of D. Ferdinand

Centre: Commanded by Ferdinand, it included the royal guard and forces of several hidalgos, like Count of Lemos and the mayordomo mayor Enrique Enriquez. It was formed mainly by popular militias of several cities like Zamora, Ciudad Rodrigo or Valladolid.[26]

Right wing: it had 6 divisions ("batallas" or "battles") of light cavalry or jennets,[26][27] commanded by their captains: Álvaro de Mendoza (the main captain), the Bishop of Ávila and Alfonso de Fonseca (these two men shared the command of one battle), Pedro de Guzmán, Bernal Francés, Vasco de Vivero and Pedro de Velasco. This wing is sometimes called vanguard as some of his men closely followed the Portuguese from Zamora to Toro. It was divided in two lines: five battles at the forefront and one in the rear.[27]

Left wing: here were many knights with heavy armours, divided in 3 corps: the left one, near the Portuguese, commanded by Admiral Enríquéz; the centre one, led by Cardinal Mendoza, and on the right, the force headed by the Duke of Alba. It was the most powerful.

Reserve forces: the men of Enrique Enríquez, Count of Alba de Aliste (King Ferdinand's uncle and Galicia's governor, who would be taken prisoner by the Portuguese); and the horsemen from the marquis of Astorga.

The foot soldiers were in the middle of all those battles. In practical terms, the Isabelist army fought on two separate fronts: right wing and left-centre or Royal Battle (due to the presence of Ferdinand).

Portuguese-Castilian army of Afonso V / The Perfect Prince

Centre: commanded by Afonso V, it was formed by the knights of several noblemen from his House and the Castilian knights loyal to D. Juana led by Rui Pereira. It also had 4 bodies of footmen with their backs turned to the Duero River.

Right wing: troops of some Portuguese nobles and the Castilians of the Toledo's Archbishop, Alfonso Carrillo.

Left wing: here were the elite troops of the kingdom (chevaliers) together with the army's artillery (arquebusiers) and the javelin throwers. It was commanded by the Perfect Prince, who had as his main captain the Bishop of Évora. It included a rear guard battle under Pedro de Meneses.[28]

Because of the split of leadership between the King and Prince, the Portuguese army also fought divided into two parts which didn't help each other:[29] left wing or Prince's battle and right-centre or Royal Battle.

Battle

The Perfect Prince defeats the right wing of Ferdinand's army

The forces of Prince John and of the Bishop of Évora, formed by arquebusiers, javelin throwers and by the Portuguese elite knights, screaming "St. George! St. George!", invested the 6 bodies or battles in the right wing of the Castilian army. The Prince attacked the five advanced battles while the battle of Pedro de Meneses attacked the other one.[30] The Castilian forces (which were very select)[3] withdrew in disorder, after suffering heavy losses.[31]

Chronicler Hernando del Pulgar (Castilian): "promptly, those 6 Castilian captains, which we already told were at the right side of the royal battle, and were invested by the prince of Portugal and the bishop of Évora, turned their backs and put themselves on the run"'.[26]

Chronicler Garcia de Resende (Portuguese): "and being the battles of both sides ordered that way and prepared to attack by nearly sunshine, the King ordered the prince to attack the enemy with his and God's blessing, which he obeyed (...). (...) and after the sound of the trumpets and screaming all for S. George invested so bravely the enemy battles, and in spite of their enormous size, they could not stand the hard fight and were rapidly beaten and put on the run with great losses." [32]

Chronicler Juan de Mariana (Castilian): “ ... the [Castilian] horsemen ... moved forward(...).They were received by prince D. John... whose charge... they couldn’t stand but were instead defeated and ran away.”[33]

Chronicler Damião de Góis (Portuguese): "... these Castilians who were on the right of the Castilian Royal battle, received [the charge of] the Prince’s men as brave knights invoking Santiago but they couldn’t resist them and began to flee, and [so] our men killed and arrested many of them, and among those who escaped some took refuge ... in their Royal battle which was on the left of these six [Castilian] divisions." .[30]

Chronicler Garibay (Basque): “ ... D. Alfonso de Fonseca first and then Álvaro de Mendoza ... and other [captains] begged the King [Ferdinand] permission to be the first to attack the Prince’s squad ... which was the strength of the Portuguese army, and the King authorized them, provided that the six battles named above remained together (...). And facing the Prince’s squads ... they were defeated, many of them dying due to artillery and javelin throwers ... and this way, the victory in the beginning was for the Portuguese ...”[34]

The Prince's men pursued the fugitives along the land. The Prince, in order to avoid the dispersion of his troops, decided to make a halt: "and the prince, as a wise captain, seeing the great victory God had given to him and the good fate of that hour, chose to secure the honour of victory than follow the chase."( Garcia de Resende)[32] But some of his men went too far ( Rui de Pina says during a league, 5 km)[35] and paid the price: "and some of the important people and others ... in the heat of victory chased [the fugitives] so deeply that they were killed or captured."[35] According to Rui de Pina, this happened because some of these fugitives, after a hard chase, gathered with one of Ferdinand's battles on the rear and faced the most temerarious pursuers. Pulgar confirms this post chase episode: "Many of those who were on those 6 Castilian battles defeated by the Prince of Portugal at the beginning, seeing the victory of the other king's battles on their respective side [left wing and centre], assembled with the people of the King and fought again” (3 hours after the beginning of the battle, according to him).[26]

Pulgar justifies the defeat of the Isabelistas with the fact that the Prince's battle attacked as a block, while the Castilians were divided in 6 battles. So, each of them was successively beaten off without benefiting from the help of the others. Other motive appointed by the same chronicler was "the great loss" suffered by the Castilians as a result of the fire from the many arquebusiers in the Prince's battle.[26] Zurita adds that the Prince successfully attacked with such "impetus" that the remaining men of the Castilian army became "disturbed".[3]

These events had important consequences. The Portuguese chroniclers unanimously[30][32][35] stated what Rui de Pina synthesized this way: " ... king D. Ferdinand ... as soon as he saw defeated his first and big battles [on the right], and believing the same fate would happen to his own battles at the hands of King Afonso's battles, was counselled to withdraw as he did to Zamora".[35]

Among the Castilians, Pulgar – the official chronicler of the Catholic Monarchs – says that Ferdinand withdrew from the battlefield for other reasons. Its justification: "the King promptly returned to the city of Zamora ["volvió luego"] because he was told that people from the King of Portugal, located in the city of Toro on the other side of the river, could attack the "estanzas" he left besieging the Zamora's fortress. And the cardinal and the duke of Alba stayed on the battlefield (...)."[26]

Not only Pulgar reveals that Ferdinand left the battlefield before cardinal Mendoza and the duke of Alba, but the expression "promptly returned" seems to indicate that the King stayed a small time on the battlefield, delegating the leadership on these two main commanders.[36] On the other hand, it was highly improbable that Ferdinand risked helping Zamora in a Royal battle which was deciding the destiny of the entire kingdom of Castile. It would be inconceivable that the Portuguese garrison of Toro dared to attack the powerful and distant city of Zamora instead of helping the forces of his King and Prince which were fighting with difficulties practically at its gates.

The victorious Prince's forces (which included the best Portuguese troops) were still on the field and were continuously raising their numbers with dispersed men converging to them from every corner of the field.[26][32][35][37][38] According to the chivalry costumes of that time, to withdraw from the battlefield under these circumstances instead of confronting this new threat and not remaining 3 days on the battlefield -as a sign of victory- [39] would be the proof that he had not won.

Indeed, it is much more probable that Ferdinand had retreated to Zamora in the beginning of the battle as a consequence of the defeat of the right side of his army (things could get worse).[40] However, there's a sharp contrast between the prudent but orderly retreat of Ferdinand to Zamora and the precipitated escape of Afonso V to avoid imprisonment.

The Royal Battle of Ferdinand defeats the Royal Battle of Afonso V

In the meantime, the other Castilian troops were fighting a fierce combat with their direct opponents. The Castilian centre charged the Portuguese centre while the Castilian left wing, superiorly commanded by Cardinal Mendoza and Duke of Alba, attacked the Portuguese right wing: " ...those from the battle of the King [Castilian centre] as well as those...from the left wing, charged [respectively] against the battle of the King of Portugal...and against the other Portuguese of their right wing." (Pulgar)[26]

Sensing the hesitation of his forces because of the Portuguese attack on the other end of the battlefield, the cardinal rode forward and shouted, "here is the cardinal, traitors!".[3] He would be wounded but kept fighting with bravery.

The Portuguese started to break. The struggle around the Portuguese royal standard was ferocious: having the flag carrier's (the ensign Duarte de Almeida) hand cut off, he transferred the banner to the remaining hand which was also cut off.[30][32][35] So he sustained the standard on the air with his teeth until he fainted under the wounds inflicted by the enemies which surrounded and captured him.

Afonso V, seeing his standard lost and supposing he had equally beaten his son’s forces (which were smaller than his) sought death in combat,[30] but was prevented from doing so by those around him. They took him to Castronuño where he was welcomed by the alcalde.

By then, the Portuguese disbanded in all directions and many of them drowned in the Duero River because of the darkness and confusion. The Castilians captured 8 flags and sacked the Portuguese camp.[26] Bernaldez painted a grandiose picture of the loot mentioning many horses, prisoners, gold, silver and clothes, which was doubtful given the dark and rainy night described by the chroniclers. In fact, Pulgar recognizes that the product of the loot was modest: "and the people who participated on the battle during the previous day divided the captured spoils: which were in small quantity because it was a very dark night".[41]

Pulgar:"At last the portuguese couldn’t stand the mighty force of the castilians and were defeated, and they ran seeking refuge in the city of Toro.(...) [the] Portugal's King seeing the defeat of his men, gave up of going to Toro to avoid being molested by the men of the King [Ferdinand], and with three or four men of all those who were responsible for his security went to Castronuño that night. (...) consequently many Portuguese were killed or taken prisoners..."[26]

Pulgar wrote that a large number of both Castilians and Portuguese died in the battle, but while the Castilians died fighting, the Portuguese drowned while trying to escape by swimming across the river Duero.

Rui de Pina justifies the Portuguese Royal Battle's defeat with the fact that the best Portuguese troops were with the Prince and were missed by the King, and also because there were many arquebusiers in the Castilian Royal Battle whose fire scared the Portuguese horses.[35]

With the darkness of the night and the intense rain, chaos reigned. There were dispersed men from all sides: fugitives from the Castilian right wing, Portuguese pursuers, fugitive soldiers from the Portuguese King, the Cardinal Mendoza’s men and the Duke of Alba’s men were divided between pursuing the Portuguese and sacking their spoils and still; the Prince’s men returned in the meantime.The battlefield became a very dangerous place where the minimal error could lead to death or imprisonment. As an example and according to Pulgar, some Portuguese shouted "Ferdinand, Ferdinand!"[26] to lure their pursuers making them think they were Castilians.

As a consequence of this triumph, Ferdinand promptly sent a letter to the cities of Castile claiming victory,[42] but without mentioning neither the defeat of part of his forces nor the retreat of his remaining troops when faced with the forces of Prince John, who possessed the camp and also claimed victory.

Later, the Perfect Prince also sent a letter to the main cities of Portugal,[42] Lisbon and Porto, ordering the commemoration of his triumph on the battle of Toro (but not mentioning his father's defeat) with a solemn procession on each anniversary of the battle.

Isabella immediately ordered a thanks giving procession at Tordesillas, and in many other cities feasts and religious ceremonies were organized to celebrate the great "victory God has given to the King and to her people."[43] She would also build a magnificent commemorative Gothic temple at Toledo, the Monastery of S. Juan de los Reyes, to dissipate any doubts and perpetuate her victory.

As the Historian Justo Gonzalez summarizes: "Both armies faced each other at the camps of Toro resulting in an undecided battle. But while the Portuguese King reorganized his troops, Ferdinand sent news to all the cities of Castile and to several foreign kingdoms informing them about a huge victory where the Portuguese were crushed. Faced with these news, the party of “la Beltraneja" [Juana] was dissolved and the Portuguese were forced to return to their kingdom."[44] The key of the war was the Castilian public opinion, not the Portuguese.

The Perfect Prince becomes master of the battlefield

Meanwhile Prince John returned after a brief chase, defeating one of the Castilian battles where the men were dispersed looting the spoils of the defeated Portuguese. However, faced with other enemy battles, he abstained from attacking and put his men in a defensive position on a hill. He lighted big fires and played the trumpets to guide all the Portuguese spread throughout the camp towards him and to defy the enemy. He acted this way because, according to the chronicler Álvaro Chaves, the Prince's forces were under-numbered as most of his men had gone in pursuit of the adversaries: "(...) [the Prince] turned against the battles of king D. Ferdinand, but because the people from his battles spread in the pursue of the defeated, the enemy's battle outnumbered the few men that remained with him, but in spite of that he attacked and defeated it and he went on until he faced other enemy battles, and then he stopped his battle to recover some of his dispersed men (...) because the enemy had the triple of his people."[45]

Pulgar: "And because the people of his father and King were defeated and dispersed, the Prince of Portugal went up to a hill and played the trumpets and lighted fires in order to recover some of the fugitives and stood on with his battle..."[26]

The Prince's men took some prisoners, among them King Ferdinand's uncle, D. Enrique, Count of Alba de Liste, and for his great joy, they retook his father's royal standard as well as the Castilian noble who carried it, Souto Mayor (according to the chroniclers Rui de Pina,[35] Garcia de Resende[32] Damião de Góis[30]).

With the Prince's forces increasing continuously,[26][32][35][37][38] no military leader could be considered winner without defeating this new threat, which included the Portuguese elite troops who had defeated the Castilian right wing. Zurita: "This could have been a very costly victory if the Prince of Portugal, who always had his forces in good order, and was very near the river banks, had attacked our men who were dispersed and without order".[3]

The Cardinal Mendoza and the Duke of Alba began to join their dispersed men to remove the new threat: "against who [Prince John] the Spain's cardinal as well as the Duke of Alba intended to go with some men that they were able to collect from those returned from the chase and from those who were spread around the camp capturing horses and prisoners..." ( Pulgar).[26]

Two great heterogeneous battles (a Portuguese and a Castilian one) formed this way, standing face to face and playing musical instruments to intimidate each other:[35] "(...) so close were the men from one part and the other, that some knights went out of the battles to invest with the spears [individual combats]" (Álvaro Lopes).[45]

But the Cardinal and the Duke of Alba couldn't convince their men to move and attack the Prince's forces: "(...) and they couldn't join and move the men" (Pulgar).[26] That's corroborated by the Portuguese chronicler Garcia de Resende: "being very close to him [the Prince] so many men of King D. Ferdinand, they didn't dare to attack him because they had seen his men fighting so bravely and observed the security and order of his forces (...)"[32]

Pulgar felt the necessity to justify the fact that the Castilians, which assumed the victory, didn't attack the victorious Prince and have instead retreated to Zamora: "(...) because the night was so dark they [the Castilians] couldn't neither see nor recognize each other and because the men were so tired and haven't eaten all day as they left Zamora by morning (...) and turned back to the city of Zamora."[26]

Those circumstances which applied to the enemy as well, didn't explain the Castilian behaviour: the chronicles of both sides show that the Prince's battle kept increasing (making a "gross battle"),[26][32][35][37][38] because towards it moved many defeated and fugitives from the Royal Battle and also the Prince's men coming back from the enemy's chase, and even contingents of soldiers from Toro,[35] which crossed the battlefield to reinforce the Prince. Thus, if all these men could reach the Prince, the Castilians could do it too, especially because the two battles (the Portuguese and the Castilian) were so proximal that the men could listen to each other: "(...) being so close to each other [the Portuguese and the Castilians] that they could hear what they talked about (...)"[32] (Garcia de Resende).

At last the Castilians withdrew in disorder to Zamora.

Rui de Pina: "And being the two enemy battles face to face, the Castilian battle was deeply agitated and showing clear signs of defeat if attacked as it was without King and dubious of the outcome.(...) And without discipline and with great disorder they went to Zamora. So being the Prince alone on the field without suffering defeat but inflicting it on the adversary he became heir and master of his own victory".[35]

Damião de Góis: "being the night so advanced (...) the Castilians left the camp in small groups (...) and neither the Cardinal of Castile nor the duke of Alba could impose them order; they also went to Zamora with the men who remained with them in the most silent way possible as all the people had fled (...) and the Prince realizing their retreat didn’t pursue them (...) because he feared [that the Castilian retreat was] a war trap, but that wasn’t the intention of the Castilians because by morning not a soul was seen on the field(...), resulting in a victorious Prince with all his people in order(...)”[37]

Álvaro de Chaves: "They abruptly left the camp towards Zamora as defeated men"[45]

Garcia de Resende: "And after the Prince had been most of the night on the battlefield, and seeing that the enemy had fled leaving no soul behind, and having nothing more to do, he decided to stand on the camp for three days (...)”.'[32] He would be convinced[32][35] by the Toledo's Archbishop to stay there only 3 hours as a symbol of the 3 days.[39]

After defeating his direct opponents and because of the dark and rainy night, Prince John's tactical choice had been to prevent the dissemination of his forces during the subsequent chase, slowly gathering the scattered men from all proveniences, in order to recover his lost operational power and attack the Castilians early the next day.[37]

The Prince made a triumphal march towards Toro, carrying his Castilian prisoners,[37] and "with his flags draping and at the sound of trumpets."[32] But very soon the sadness dominated him because nobody knew where his father, the King, was. Besides that, the city of Toro was chaotic, with its gates closed because the Portuguese mistrusted their Castilian allies who they accused of treason and blamed for the defeat of their King.[43]

The Prince ordered the gates to be opened, restored the order and on the next day he sent a force to Castronuño, which brought back the King. He also "sent some of his captains to the battlefield to bury the dead and to redact a victory act, which was entirely made without contradiction".[45]

The fact that the Portuguese remained masters of the battlefield is documented in contemporary sources from both sides:[48] Pulgar first states that King Ferdinand withdrew from the battlefield to Zamora before Cardinal Mendoza and the Duke of Alba,[26] and then he declares that his army (now under command of the Cardinal and Duke) also withdrew from the battlefield to Zamora – after an attempt to attack Prince John, who was thus left in possession of the battlefield.[26]

And Bernaldez explicitly wrote that the Prince only returned to Toro after the withdrawal of Ferdinand’s army: “The people of King D. Ferdinand, both horsemen and peons, plundered the camp and all the spoils they found in front of the Prince of Portugal, who during that night never moved from top of a hill, until (...) King D. Ferdinand left to Zamora with his people plus the spoils. Then, the Prince of Portugal left to Toro.”[2]

Juan de Mariana corroborates him: “(...) the enemy led by prince D. John of Portugal, who without suffering defeat, stood on a hill with his forces in good order until very late (...). Thus, both forces [Castilians and Portuguese] remained face to face for some hours; and the Portuguese kept their position during more time (...)"[33]

Balance

The Portuguese chronicles agree with the Castilian official chronicler Pulgar in most of the essential facts about the battle of Toro. Both show that the strongest part of each army (the Castilian and Portuguese left wings, respectively led by Cardinal Mendoza and Prince John) never fought each other: only at the end, says Pulgar, there was an unsuccessful attempt of Cardinal Mendoza and Duke of Alba to attack the forces of the Prince, quickly followed by a withdrawal of the Castilian army to Zamora.[26] This was probably decisive for the final outcome of the battle, because each one of the armies won where it was stronger. Naturally the Castilian and Portuguese chroniclers focused their attention on their respective victory.

- Each side had a part of its army defeated and one part winner [3][26][30][32][33][35] (the Castilian army had its right wing defeated and its left-centre winner. The Portuguese army had its right-centre defeated and its left wing victorious);

- Both Kings left the battlefield:[2][26][30][32][35] Ferdinand to Zamora in an orderly way (probably after the victorious attack of the Prince) and Afonso V fled after the defeat of his Royal Battle by the Castilian left-centre;

- The battlefield[48] stood in possession of the Prince's forces[2][26][32][33][35][37][45] increased by many combatants spread throughout the camp which converged to him (tactical victory);

- The Portuguese royal standard was retaken by the Prince's men;[30][32][34][35]

- The losses were large in both[26][45] armies (in relative terms) but small[33] in absolute value;

- Both sides proclaimed victory;[1]

- The battle represented a victory for the aspirations of Isabella to the throne of Castile, regardless its uncertain military outcome.[49] As the Spanish historian Ana Isabel Carrasco Manchado puts it: "It's difficult to assess the importance of this battle from a military perspective. Indubitably, it represented a moral turning point for the party of Isabella and Ferdinand."[42]

The polemic

Indeed, the Battle of Toro consisted almost in two separated combats: one won by the troops of Prince John and the other by Ferdinand's forces.

None of the intervenients had access to a global vision of the battle due to the geographic separation of the two engagements and also because of the darkness, fog and rain. Therefore, it is natural that separated combats with different outcomes have originated different versions among the chroniclers of both sides, and as revealed by Pulgar, between Castilians and Portuguese: "there held the old question about the force and bravery”.[26]

Due to all of this, the only way to get a historical and impartial reconstitution of the Battle of Toro is by analyzing the sources of both sides.

In fact, there is not an essential contradiction between the victory proclamations of both sides. As observed by the Spanish academic Luis Suárez Fernández: "But this document [Ferdinand's letter communicating his victory to the cities] of great importance does not contain more than the bare attribution of the victory to the Castilian arms, and doesn’t contradict in any way the reality of one part of the Portuguese army, winner of one of the [Castilian] wings, staying on the camp and being able to retreat on the next day without being hindered. Neither is contradiction in the admission that being a dubious business it represented a very great political victory to Ferdinand and Isabella as it finished what still remained from the Juana’ s party."[50]

The Portuguese royal standard

The Portuguese chroniclers unanimously affirm that the Portuguese royal standard was retaken[30][32][35] to the enemy by Gonçalo Pires, whose nickname became Bandeira (in Portuguese it means "Flag") in memory of that deed and so he became Gonçalo Pires Bandeira (coat of arms chart conceded on 4 July 1483 by King John II).[51] The Castilian who carried it – Souto Mayor – was captured[30][32][35] and the others fled.

On the other hand, although most of the Castilian chronicles recognize the loss of the standard by the Castilians, they are contradictory.[52] One of the chroniclers (Bernaldez) even wrote that the Portuguese ensign was killed,[2] whereas he was captured[26][30][32][35] and later returned to Portugal.

At 1922 several academics among them Félix de Llanos y Torriglia studied the Portuguese standard hanged at the Chapel of the New Kings (Toledo’s cathedral) and concluded that the standard was probably Castilian and probably from the 14th century (the Battle of Toro was fought during the 15th century).[53] In 1945, Orestes Ferrara also investigated the standard and concluded that it couldn't be the one carried by Afonso V at the Battle of Toro.[54] It is necessary to take into account that several Portuguese banners were captured in the battle (eight, according to Pulgar).[26]

There's additional evidence that the royal standard was indeed retaken by Gonçalo Pires Bandeira since the Portuguese chronicler Rui de Pina made a hard critic to the King himself. He accuses Afonso V of ingratitude towards a man who served him so well and retook the lost flag: the royal rent given to him was so miserable that he had to work in agriculture in order to survive (the manual work as a stigma to the medieval mentality). This was certainly correct because other way it would be a gratuitous slander to the King Afonso V (uncle of the monarch Manuel I to whom Rui de Pina wrote his chronicle) from which his author wouldn't benefit at all.[55] Besides, the Portuguese chronicles are corroborated by three Spanish chroniclers:

Scholar Antonio de Nebrija (Castilian): “The Lusitanian standard is captured, which was a valuable insignia, yet by the negligence of Pedro Velasco and Pedro Vaca, to whom it was entrusted, as [already] mentioned, it is subsequently taken up by the enemy.”[56]

Chronicler Garibay (Basque): “The king of Portugal (...) seeing lost, one first time, his Royal standard and captured the ensign, who was taken to Zamora and stripped of his weapons which ...were exposed in the Chapel of the New Kings, Toledo's Church, (...) even though the standard, for negligence (...) was taken by the Portuguese.”[34]

Royal Cosmographer and Chronicler Pedro de Medina (Castilian): “The Castilians invested the Portugal’s standard ...and took it easily due to the cowardly and soft resistance from the ensign and its guards. The ensign was captured and later taken to Zamora...but the standard was not taken because...some Portuguese chevaliers regained it after fighting with bravery.” [57]

In medieval warfare, the royal standard was not a mere flag. Its loss was almost equivalent to losing the battle.

The Battle of Toro in numbers

Time

The fight would have taken between more than an hour[30] (according to Damião de Góis) and more than 3 hours[26] (Pulgar).

The size of the armies

Both armies had a similar number of men: around 8,000 soldiers.

According to Bernaldez, the only chronicler who gives total numbers, the Portuguese army had 8,500 men (3,500 horsemen plus 5,000 peons)[2] while Ferdinand's army had 7,500 men (2,500 horsemen and 5,000 peons) when they left Zamora.[2] So, the Portuguese army had a light advantage of 1,000 horsemen.

Bernaldez wrote that the Portuguese army who besieged Zamora had 8,500 men. The siege of this city started in the middle of February 1476 – fifteen days[58] after the union of the reinforcements brought by the Perfect Prince with the royal army of Afonso V (end of January 1476)[59] – and continued until the day of the battle (1 March 1476).Thus, 8,500 men is the total number for the combined Portuguese forces at the Battle of Toro since the Portuguese army who fought it was precisely the army who abandoned the Zamora's siege and withdrew to Toro, where it was reached by the former besieged Isabelist army. From this initial number of 8,500 men, it is necessary to discount the losses by desertion, disease,[60][61] and fight during the Zamora's siege, after 15 days of hard winter,[2] putting the final figure in more than 8,000 Luso-Castilians.

From the Portuguese side, this number reflects the high desertion suffered by its initial army (14,000 footmen and 5,600 chevaliers – but many of them were used as garrison of strongholds and thus did not fight in the Battle of Toro),[62][63] due to the unpopularity of the war among them. Especially after the failure of Burgos as it is told by Rui de Pina: “(...) many Portuguese without the will of serving the King came back to the kingdom [Portugal]".[64] The Portuguese captains complained that while they were in Castile, their undefended lands in Portugal were set on fire and looting by the enemy.[65] Other reasons were the high losses by disease,[66] especially fevers from the hot and also because the Luso-Castilian army included many Castilian contingents who easily and massively changed sides after the aborted expedition to Burgos and its consequent fall on 28 January 1476. From all the great Castilian nobles who initially supported Juana, only[59] the Archbishop of Toledo, Alfonso Carillo de Acuña was at the side of Afonso V on the day of the battle. After all, despite the reinforcement troops[67] brought by Prince John, when the Battle of Toro was fought, the invader army had suffered the erosion of 10 months of permanency in enemy territory.

Álvaro Lopes de Chaves, the most nationalist of the Portuguese chroniclers, wrote that the Castilian army had a small advantage of 700 to 800 chevaliers over the Portuguese army.[45] Pulgar Corroborates the similar size of both armies: "... there was little difference in the number of horsemen between both armies." [26][68]

The high numbers involving dozens of thousands of men on each army as it is mentioned in some modern records of the Battle of Toro not only do not have documentary support but are also in direct contradiction with the Historical record: the contemporaneous chronicler Andreas Bernaldez, being a Castilian and a partisan of the Catholic Monarchs, cannot therefore be accused of pulling down the numbers of the armies present at the battlefield to reduce the triumph of his King Ferdinand at Toro.

Bernaldez is also corroborated by the partial numbers of the late chronicler Zurita for the horsemen of both armies: 3,000 chevaliers to Ferdinand and 3,500 chevaliers to Afonso V.[3]

Losses

The total number of losses (dead and prisoners) was probably similar in both armies (but larger among the Juanistas) and wouldn't have been higher than one thousand men[4] among the Portuguese-Castilians and many hundreds[5] for the Isabelistas.

While Diego de Valera estimates 800 dead, Bernaldez mentions about 1,200 Portuguese dead[2] (that's the version high Portuguese losses and low Castilian losses). But the version of great Portuguese losses / great Castilian losses is much more credible, not only because it is the only one supported by the sources of both sides (Pulgar[26] and Á. Lopes de Chaves[45]), but also because Bernaldez is contradicted by no less than five chroniclers who explicitly stated that the Castilian losses were high: Pulgar, Esteban de Garibay y Zamalloa,[69] Garcia de Resende,[70] A. Lopes Chaves and Damião de Góis.[71]

Pulgar states: "(...) and many were killed in one side and on the other side (...)."[26]

Álvaro Lopes de Chaves, also an eyewitness[45] of the campaign, adds:"(...) and on the battle there were many dead, prisoners and wounded in one side and on the other side."[45]

The losses were relatively large comparing to the size of the armies in presence, but according to chronicler Juan de Mariana they were low in terms of absolute value for a battle with this political importance: "The killing was small compared with the victory, and even the number of captives was not large".[33]

Besides the chronicles, there is additional evidence pointing to low losses in the Battle of Toro: during the Lisbon courts of 1476, the procurators of Évora called the attention of Prince John to the strong contingent given by the city to his father's army. This was natural because Évora was the second most populous Portuguese city of the 15th century.[72] What is not expectable is that only 17 men from that contingent had died in the Battle of Toro,[73] as the same procurators proudly declared. This number only makes sense if we accept that the Portuguese fatalities in battle were low.

Aftermath and consequences

From a military perspective the Battle of Toro was inconclusive[74][20] but politically the outcome was the same as it would have been if the battle was a military victory for the Catholic Monarchs, because all its fruits have fallen by their side.[75][76] Isabella convoked courts at Madrigal where her daughter was proclaimed and sworn heiress of Castile's throne (April 1476).

After the battle, Afonso V – who wanted to avoid the renovation of the truces between France and Aragon, which would expire in July 1476[77] – became convinced that Portugal wouldn’t be able to impose his niece’s rights to the Castile's throne without external aid. So he departed to France seeking for help. The combined resources of Castile and Aragon had a population five times bigger[78][79] and an area five times larger than that of Portugal.

Many nobles still loyal to Juana since the Burgos episode turned sides[24] along the next months and years – like the Portocarrero and Pacheco-Girón families plus the hesitant Marquis of Cadiz – and the majority of the undecided cities and castles would bound to the Isabella's party specially the fortress of Zamora, Madrid and other places from the Central region of Castile. It was a very slow but irreversible process.

However, the bulk[80][81] of the Portuguese army stayed in Castile with Afonso V and Juana[82][83] during more than 3 months after the Battle of Toro, until 13 June 1476.[84][85] Rui de Pina and Damião de Góis wrote that only a small fraction[80][81] of the Portuguese troops returned to Portugal with the Perfect Prince – one month after the battle, first days[86] of April 1476 (Easter) – to organize the resistance[65] of the undefended Portuguese frontier from the continuous Castilian attacks. According to Juan de Mariana they were only 400 horsemen.[87]

In spite of having been weakened by the countless defections from the Juanistas to the Isabelistas, the Portuguese troops maintained a winning attitude especially in the district of Salamanca (and later around Toro), conquering[88] and burning many castles and villages. The Portuguese army even organized two large military expeditions to capture[89][90] King Ferdinand and then Queen Isabella (April 1476).

After the Battle of Toro Ferdinand's reinforced army did not attack the invading army, but with less risk besieged the Juanista strongholds (successfully even at length thanks to a clever policy of forgiveness) while negotiating with the rebel hidalgos.

The Catholic Monarchs' strategy proved to be right because time and resources were on their side: the terrible military pressure[91] exercised over the Portuguese border lands (which defensive forces were in Castile at the service of Afonso V) together with the new front of the naval warfare ( Isabella decided to attack the Portuguese at the heart of their power – the sea and the gold of Guinea)[92] made inevitable the return of the Portuguese army to Portugal.

Diplomatic solution at Alcáçovas

After the Battle of Toro the war continued, especially by sea (the Portuguese reconquest of Ceuta[93][94] besieged and taken by the Castilians except for the inner fortress, the campaign of the Canary islands,[95][96] and the decisive naval Battle of Guinea[97]), but also in Castilian and Portuguese soil.

In 1477 a force of 2,000 Castilian knights commanded by the master of Santiago, Alonso de Cárdenas who invaded the Alentejo (Portugal) is defeated[98][99] near Mourão: more than 100 Castilian knights were captured[98][99] and the others fled, according to the chroniclers Garcia de Resende and Damião de Góis.

In 1479, the same master of Santiago defeats at Albuera[100] a force of 700 or 1,000 (depending on the sources) Portuguese and allied Castilians who had invaded Extremadura (Castile) to help the rebel cities of Medellin and Mérida. According to Alfonso de Palencia the Portuguese-Castilians had 85 knights killed[101] and few prisoners,[102] but the bulk[103] of that force reached those two cities where they resisted to fierce sieges by Ferdinand's forces until the end of the conflict,[104][105] and thus increasing the bargaining power of Portugal during the peace negotiations and keeping the war’s gravity centre inside Castile and out of doors. Except for those two cities on Extremadura and other conquered places (Tui, Azagala and Ferrera),[106] all the other strongholds occupied by the Portuguese in Castile ( Zamora, Toro and Cantalapiedra)[24] as well as those occupied by their allied castilians[107] (Castronuño, Sieteiglesias, Cubillas Villalonso, Portillo, Villaba) surrendered.

Nevertheless, all the strongholds occupied by the Castilians in Portugal (Ouguela, Alegrete and Noudar)[108] were retaken by Prince John.

The exit from this impasse was reached through negotiations: the naval victory on the war[109] [110] allowed Portugal to negotiate its acquittal to the Castilian throne at the exchange[111][112] of a very favourable share of the Atlantic and possessions.

On the other side, months before the start of peace negotiations the Catholic Monarchs reached two great victories: The acknowledgement of Isabella as Queen of Castile by the French King (treaty of Saint-Jean-de-Luz on 9 October 1478), who broke this way the alliance with Afonso V, leaving Portugal isolated facing Castile and Aragon.[113]

The Pope Sixtus IV, changing his position, revoked the former bull authorizing Juana's marriage with her uncle Afonso V. This way, the legitimacy of Afonso V as King of Castile fell by its foundations.

The final balance of the war became very similar to the one of the Battle of Toro, without a conclusive victory to none of the sides: Castilian victory on the land[110] and a Portuguese victory on the seas.[110] In the peace Treaty of Alcáçovas, everybody won: Isabella was recognized Castile's Queen (in exchange for her acquittal to the Portuguese crown and the payment of a big war compensation to Portugal: 106.676 dobles of gold)[24][114] and Portugal won the exclusive domain of the navigation and commerce in all the Atlantic Ocean except for the Canary Islands (in exchange for its eventual rights over those islands which remained to Castile). Portugal also reached the exclusive conquest right over the Kingdom of Fez (Morocco). Only D. Juana, la "Beltraneja" or "the Excellent Lady", has lost a lot as she saw her rights sacrificed to the Iberian states' interests.

Propaganda

As the Spanish academic Ana Isabel Carrasco Manchado summarized:

"The battle [of Toro] was fierce and uncertain, and because of that both sides attributed themselves the victory. (...). Both wanted to take advantage of the victory's propaganda."[42]

Both sides used it. However, Isabella demonstrated a superior political intelligence and clearly won the propaganda's war around the result of the battle of Toro: during a religious ceremony at the Toledo's cathedral (2 February 1477), Isabella – who already had proclaimed herself Queen of Portugal – hung the military trophies taken from the Portuguese (flags and the armour of the ensign) at the tomb of her great grandfather Juan I, as a posthumous revenge for the terrible disaster of Aljubarrota.[115][116]

Since then the chroniclers of the Catholic Monarchs followed the official version that the Battle of Toro (1476) was a victory which represented a divine retribution for the battle of Aljubarrota (1385): one of the chroniclers (Alonso Palma, in 1479) put it exactly as the title of his chronicle –“La Divina retribución sobre la caída de España en tiempo del noble rey Don Juan el Primero”[117] ("Divine retribution for the defeat of Spain during the time of the noble King D. John the first").

After the letter[118] sent in 1475 by Pulgar (whose chronicle seems to have been personally reviewed by Isabella)[119] to Afonso V (Aljubarrota, where “(...) fell that crowd of Castilians (...) killed”)[118] the theme became recurrent.

This is well exemplified by Palencia, who not only frequently mentions Aljubarrota but also refers to the expedition that was planned by the inner circle of Isabella to send a great Castilian force to penetrate deeply into Portugal in order to recover the Castilian royal standard taken by the Portuguese on the Battle of Aljubarrota one hundred years before. There were many volunteers – hidalgos and cities like Seville, Jerez, Carmona, Écija, Cordova, and Badajoz. All this because, according to Palencia, the flag symbolized the "(...) eternal shame of our people" from the Castilian defeat at Aljubarrota.[120][121]

This obsession with Aljubarrota clearly influenced[20] the descriptions of the Battle of Toro in the Castilian chronicles.

It is important to the modern historical critic of the Battle of Toro to differentiate the facts from the official propaganda of the 15th and 16th centuries and to confront these records with those of the enemy side: for example with the chapter "How the Prince won the Battle of Toro and remained in the battlefield without contradiction" from the chronicle "Life and deeds of King D. John II" of the Portuguese chronicler Garcia de Resende.[32]

Besides literature, architecture was also used for propaganda and was influenced by Aljubarrota. The Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes (to celebrate the Battle of Toro) was also a response[122] to the Monastery of the Battle built by the Portuguese to commemorate Aljubarrota, and like the Portuguese one it was also conceived to be a royal pantheon.

On the other side, the Portuguese chroniclers focused their attention on the victory of the Perfect Prince instead of the defeat of his King, Afonso V. And they also presented the Portuguese invasion of Castile as a just cause because it was made in the defence of the legitimate Queen against a "usurper" – Isabella.

Besides the documents, there are other indicators equally important to indicate the result of the Battle of Toro, like what happened during the weeks immediately after the battle such as the attitude and behaviour of both armies, the duration of the invading army's time in the area, and even comparisons with other similar battles.

The Battle of Toro as retribution to Aljubarrota

The Battle of Toro is frequently presented as a twin battle (with opposite sign) of the Battle of Aljubarrota. Politically the comparison is legitimate: both of them were Royal Battles which decided the fate of some Peninsular Kingdoms in a way that would prove to be favourable to the nationalist party. But on military terms the difference is large[123]

Besides Afonso V's defeat, Pulgar reports that a part of the Portuguese army (his left side led by the Perfect Prince) defeated[26] during the Battle of Toro a part of the Isabelista army: its right side, and he gives a justification[26] for that.

That’s corroborated by all the four Portuguese chroniclers,[32][35][45][71] and also by Zurita and Mariana, who respectively added that, after this, the Prince’s forces remained "always in good order”,[3] and “without suffering defeat”,[33] during the whole battle (or “intact”, according to Pedro de Medina).[124]

The Portuguese-Castilians became masters of the battlefield according to all the Portuguese chroniclers and also to Pulgar,[26] Bernaldez[2] and Mariana who revealed that "the Portuguese sustained their positions during more time".[33]

Both Kings Ferdinand and Afonso left the battlefield of Toro (to Zamora and Castronuño respectively) in the night of the battle according to all chroniclers of both sides and the Portuguese recovered its lost royal standard.[30][32][34][35]

At the Battle of Aljubarrota all the parts of the Franco-Castilian army were defeated: vanguard,[125] royal battle[126] and right wing.[127] At the end of the battle, the only Castilian soldiers present at the battlefield were dead[128] or imprisoned,[123] and the Portuguese King plus his army remained there for 3 days.[129] The Castilian royal standard was taken to Lisbon and 12 hours[130] after the battle Juan I left Portuguese soil taking refuge in his mighty armada which was besieging Lisbon (3 days[131] later he sailed towards Castile) – while his entire army fled to Castile in the hours immediately[132][133][134] after the battle. The Portuguese army invaded Castile and defeated a large Castilian army in the Battle of Valverde (mid October 1385).[135][136]

After the Battle of Toro, the Afonso’s V army stayed in Castile 3 ½ months[84][85] where it launched several offensives especially in the Salamanca's district[88] and later around Toro.[88] For that he was criticized by chronicler Damião de Góis: "[Afonso V] never stopped to make raids and horse attacks along the land, acting more like a frontier’s captain than like a King as it was convenient to his royal person."[88]

Shortly after the Battle of Toro (April 1476), the Portuguese army organized two large military operations to capture[89][90] first King Ferdinand himself (during the siege to Cantalapiedra) and then Queen Isabella (among Madrigal and Medina del Campo). As noted by historian L. Miguel Duarte,[137] this was not the behaviour of a defeated army.

On the other side, the Castilian army during those 3 months after the Battle of Toro, in spite of its numerical advantage – with the massive transferences from the Juanistas to the Isabelistas plus the departure of some troops back to Portugal with Prince John – and despite of being impelled in his own territory, it neither offered a second battle nor attacked the invading army. This behaviour and attitude is an elucidative indicator of the outcome of the Battle of Toro.

There is also a number gap. In the Battle of Toro the proportion of both armies was practically 1:1, according to Bernaldez (7,500 Juanistas to 8,500 Isabelistas),[2] Álvaro L Chaves[45] and Pulgar,[26] whereas at Aljubarrota that proportion was 5:1 according to Fernão Lopes (31,000 Franco-Castilians to 6,500 Anglo-Portuguese)[138] or "at least 4:1"[139] according to Jean Froissart. Elucidative is the attitude of the Castilian chronicler Pero López de Ayala, who besides being a military expert and a royal counsellor, participated on the Battle of Aljubarrota: he described minuciously the disposition and the numbers of the Anglo-Portuguese army but understandably he didn't say a word about the soldiers’ number of his own army.[140]

In the Battle of Toro the casualties (dead and prisoners) were similar[26][45] in both armies according to Pulgar and Álvaro L. Chaves and were low[33] to J. Mariana. According to Diego de Valera the Portuguese suffered 800 dead while Bernaldez, who doesn’t quantify the Castilian losses, gives a total of 1,200 dead to the Portuguese.[4]

At Aljubarrota, Fernão Lopes reveals that the Castilians lost 2,500 men at arms [127] Plus a “huge crowd”[127] of “little people”, men without a (noble) name (foot men, javelin throwers, jennets) and in the subsequent 24 hours the fugitives suffered a terrible bloodbath in the neighbouring villages at the hands of the local.[141]

The so-called "monk of Westminster", who wrote near 1390 possibly recording the testimony of English participants, puts the total losses (common people and men at arms) in more than 7,500 dead.[142][143] (to Froissart they were 7 to 8 thousand[144] dead).

As for the prisoners, Ximenes de Sandoval, the great Aljubarrota Spanish expert, estimated in his classic work[145] the grand total for the Franco-Castilian losses: 10,000 men: 3,000 dead on the battlefield plus 3,000 dead on the near villages and 4,000 prisoners.

Only losses of this magnitude could justify the national mourning decreed by Juan I –which lasted two years[146] – and also the prohibition to participate in any public and private feast during that time:[147] "Nowadays, our kingdom has suffered such great loss of so many and so important chevaliers like those who died on the present war [with Portugal] and also because in this time came such great dishonour and ruin to everyone of our kingdom that it is great the pain and shame residing in our heart."[148][149] (Juan I at the Valladolid courts −1385, December).

Ten days[150] after the Battle of Toro, a few Portuguese deserters[151] were imprisoned when they tried to reach Portugal through Sayago, on the frontier, and some of them were killed or castrated.

Desertion among the Portuguese was very high before[64] the Battle of Toro, especially after the Burgos episode, and after this battle the number increased: "And many of the Portuguese that left the battle returned to Portugal whether on foot or by horse." ,[41] wrote Pulgar.

When some Portuguese proposed to buy a free transit document (one silver royal for each man) to avoid fighting, the Cardinal Mendoza counselled Ferdinand to send an order to spare any prisoner and to not offer resistance to those Portuguese who tried to cross the frontier because other way they will have no alternative except to fight and thereby prolonging the war and destruction inside Castile: "when this was known to the King, it was debated in his council if they should permit the returning of the Portuguese to Portugal in security. Some chevaliers and other men from the King's army whose sons and brothers and relatives were killed and wounded on the battle (...) worked to provoke the King (...). And brought into the King's memory the injuries and the cruel deaths inflicted by the Portuguese to the Castilians in the battle of Aljubarrota (...).The cardinal of Spain said: (...) Pero Gonzalez de Mendoza my great grandfather, lord of Aleva, was killed on that so called battle of Aljubarrota (...) and in the same way perished some of my relatives and many of Castile's important personalities. (...) do not think in revenge (...). It is sure that if the passage was made impossible for those [Portuguese] who go, they will be forced to stay in your kingdoms, making war and bad things (...). After hearing the cardinal's reasons, the King sent an order to not preclude the passage of the Portuguese, and to not cause them harm in any way." (Pulgar).[41] It was a variant of the principle attributed to Sun Tzu: "when enemy soldiers leave your country cover them with gold", except that in this case it was the enemy soldiers who left silver in Castilian territory in exchange for their free transit.

This situation of the Portuguese deserters[151] trying to cross the frontier by their own risk, several days[150] after the Battle of Toro, is not comparable to the bloodbath suffered by the Castilian fugitives at the hands of the population in the 24 hours after the Battle of Aljubarrota.[141] After all, those Portuguese deserters had some capability to make war and antagonize the Castilians who might try to capture them (as was recognized by the Cardinal Mendoza), whereas near the Aljubarrota battlefield the Castilian soldiers’ thought was to survive the carnage. Their bargaining power and silver were useless.

In the Portuguese historiography and imaginary, the Battle of Toro wasn’t considered a defeat but an inconclusive engagement or even a victory – and not just exclusively in Portugal,[152][153][154] especially for those of the 15th to the 18th centuries.

In Castile the Battle of Aljubarrota was considered a national tragedy: the Castilian chronicler Álvaro Garcia de Santa María reports that during the peace negotiations at 1431 (as late as nearly half a century after Aljubarrota) the members of the Castilian royal council didn't want to sign the peace treaty and offered a hard resistance because many of them "have lost their grandfathers, or fathers or uncles or relatives in the battle of Aljubarrota and wanted to avenge the great loss they had suffered on that occasion"[155]

"Revenge" would finally come two centuries after Aljubarrota at the Battle of Alcântara (1580) when a Spanish army defeated the Portuguese supporters of António, Prior of Crato and incorporated Portugal into the Iberian Union.

The Battle of Toro and modern Spain

The great political genius of the Catholic Monarchs was to have been capable of transforming[19][156][157][158] one inconclusive battle[159][160] into a great moral, political and strategic victory, which would not only assure them the crown but also create the foundations of the Spanish nation. The academic Rafael Dominguez Casas: “...San Juan de los Reyes resulted from the royal will to build a monastery to commemorate the victory in a battle with an uncertain outcome but decisive, the one fought in Toro in 1476, which consolidated the union of the two most important Peninsular Kingdoms.”[161]

Soon came the Granada conquest, the discovery and colonization of the New World, the Spanish hegemony in Europe, and at last the "Siglo de Oro" (the Gold Century) whose zenith was reached with the incorporation of Portugal and its fabulous empire into the Iberian Union, creating a web of territories "where the sun never sets".

Nowadays, the relationship between Spain and Portugal is excellent and battles like the one of Toro seem part of a remote past: some Portuguese and Spanish commonly refer to each other by the designation of "nuestros hermanos", which means “our brothers” in Spanish.

Notes

- ^ a b Portuguese victory: Rui de Pina, Garcia de Resende, Álvaro Lopes de Chaves, Damião de Góis (4 Portuguese chroniclers). Castilian victory: Hernando del Pulgar, Andreas Bernaldez, Alonso de Palencia, Alonso Palma and Juan de Mariana (5 Castilian chroniclers), Jeronimo Zurita (Aragonese chronicler), and Esteban de Garibay (Basque chronicler).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o ↓ Andrés Bernaldez – Historia de los Reyes Catolicos, Tome I, chapter XXIII.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i ↓ Jerónimo de Zurita – Anales de Aragon volume VIII, book XIX, chapter XLIV.

- ^ a b c According to ↓ Diego de Valera the Luso-Castilians had 800 dead (Crónica de los Reyes Católicos, 1927, volume 8, chapters XX and XXI), while to ↓ Bernaldez they suffered 1,200dead (Historia de los Reyes Católicos , tome 1, chapter XXIII, p.61). These figures are probably inflated since ↓ Juan de Mariana wrote that the Portuguese losses – both dead and prisoners – were low: “The killing was small...and also the number of prisoners was not large; ...” (Historia general de España, Tome V, book XXIV, chapter X, p.300). ↓ Zurita can only list 3 names of Portuguese noblemen killed in the battle (Anales de Aragon, Volume VIII, book XIX, chapter XLIV) and the partial casualties reported in the courts of 1476 by the procurators of Évora point to very low numbers ↓ (Gabriel Pereira – Estudos Eborenses, Historia- arte- archeologia, Évora nos lusiadas, ed. Minerva eborense, 1890, p. 9 and 10.)

- ^ a b The casualties were similarly "high" in both armies (as stated by ↓ Pulgar in Crónica de los señores reyes católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragon, chapter XLV, p. 88, and by chronicler ↓ A. Lopes de Chaves in Livro de apontamentos (1483–1489), Lisboa, 1984, book description). However, the Isabelistas losses were probably lower than the Juanistas losses due to the (Portuguese) drowned in the Duero River. This last number was close to the number of Portuguese killed in combat (↓ Pulgar, Crónica de los señores reyes católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragon, chapter XLV, p. 88). Even the Cardinal Mendoza was wounded by a spear and several members from the Castilian royal council who met 10 days after the battle of Toro lost relatives there (Pulgar – Crónica de los señores reyes católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragon, chapter XLVII, p. 91).

- ^ ↓ French historian Joseph-Louis Desormeaux: "...The result of the battle was very uncertain; Ferdinand defeated the enemy´s right wing led by Alfonso, but the Prince had the same advantage over the Castilians" in Abrégé chronologique de l´histoire de l´Éspagne, Duchesne, Paris, 1758, 3rd Tome, p. 25.

- ^ ↓ French historian M. de Marlés: "...the infant [Prince John] and the duke [of Alba, the main Castilian commander] remained masters, each on his side, of the battlefield. The latter withdrew during the night ;” in Histoire de Portugal, Parent-Desbarres, Éditeur, Paris, 1840, page 190.

- ^ ↓ German academic Heinrich Schaeffer: “The two Kings had left the battlefield before the action was decided... In the end, the prince stood alone on the field as a winner after the defeat of the main [Portuguese] body. Until that defeat, [Prince] John chased the six divisions beaten by him..." in Histoire de Portugal, translated from German into French by H. Soulange-Bodin, Adolphe Delahays, Libraire-editeur, Paris, 1858, p.554-555.

- ^ ↓ British historian Edward McMurdo: “...the battle of Toro in which both adversaries proclaimed themselves conquerors, (...) it was no more than a success of war sufficiently doubtful for either party, ...were it not that the cause of D. Alfonso V was already virtually lost by the successive defection of his partisans..." in The history of Portugal from the reign of D. Diniz to the reign of D. Alfonso V, 2nd volume, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1889, p. 515. ISBN 978-1150496042

- ^ ↓ historian Germán Carrera Damas: "But Alfonso failed to defeat the supporters of Isabella and Ferdinand, and the battle of Toro (1476) resulted indecisive." in História general de América Latina, Ediciones UNESCO/ Editorial Trotta, Paris, 2000, volume II, p. 35.

- ^ ↓ Irish historian John B. Bury: “After nine months, occupied with frontier raids and fruitless negotiations, the Castilian and Portuguese armies met at Toro...and fought an indecisive battle, for while Afonso was beaten and fled, his son john destroyed the forces opposed to him.." in The Cambridge Medieval History, Macmillan, 1959, Volume 8, p.523.

- ^ ↓ French historian Jean Dumont: “In the centre, leading the popular milicia, Ferdinand achieves victory taking the standarts of the King of Portugal and causing his troops to flee. In the [Portuguese] right wing, the forces of Cardinal [Mendoza] and Duke of Alba and the nobles do the same. But in the [Portuguese] left Wing, in front of the Asturians and Galician, the reinforcement army of the Prince heir of Portugal, well provided with artillery, could leave the battlefield with its head high. The battle resulted this way, inconclusive. But its global result stays after that decided by the withdrawal of the Portugal’s King [not as its direct consequence since this only happened three months and a half later, on 13 June 1476, after several military operations], the surrender of the Zamora’s fortress on Mars 19, and the multiple adhesions of the nobles to the young princes.", in La "incomparable” Isabel la Catolica/ The imcomparable Isabel the Catholic, Encuentro Ediciones, printed by Rogar-Fuenlabrada, Madrid, 1993 (Spanish edition), p.49

- ^ ↓ Spanish historian Julián María Rubio: "The solution of this conflict is also similar to the previous one. The indecisive battle of Toro, which was certainly not in its results and consequences, puts an end to the indubitable "Portuguese danger" to Castile", in Felipe II y Portugal, Voluntad, Madrid, 1927, Volume I de Manuales Hispania, p. 34.

- ^ ↓ Spanish historian Rafael Ballester y Castell: “The King of Portugal simply remained on the defensive; the first March 1476, he was attacked by Ferdinand of Aragon in front of the town of Toro. The battle was indecisive, but [with] the supporters of the Catholic Monarchs asserting their superiority, the Portuguese King withdrew" in Histoire de l'Espagne, Payot, 1928, p.132.

- ^ ↓ Marvin Lunenfeld: “In 1476, immediately after the indecisive battle of Peleagonzalo, Ferdinand and Isabella hailed the result as a great victory and called the 'Cortes' at Madrigal. The newly created prestige was used to gain municipal support from their allies...” in The council of the Santa Hermandad: a study of the pacification forces of Ferdinand and Isabella, University of Miami Press, 1970, p.27.

- ^ ↓ António M. Serrano- San Juan de los Reyes y la batalla de Toro, revista Toletum, 1979 (9), segunda época, pp. 55-70. Real Academia de Bellas Artes y Ciencias Históricas de Toledo, Toledo. ISSN: 0210-6310

- ^ ↓ Spanish historian josé Maria Cordero Torres: "...later... were those [attempts] of Alfonso V to the Castilian crown [that] also finished by tiredness and not by the indecisive battle of Toro, which was transformed by the Spanish in another Aljubarrota..." in Fronteras Hispanicas: geographia e historia, diplomacia y administracion, Instituto de Estudios Políticos, 1960, p.303.

- ^ ↓ Spanish historian Juan Contreas y Lopes de Ayala Lozoya: “This famous Franciscan convent [San Juan de los Reyes] intended to be a replica of the Batalha [the Portuguese monastery built after Aljubarrota], and was built to commemorate the indecisive battle of Toro." in El arte gótico en España: arquitectura, escultura, pintura, Editorial Labor, 1945, p. 85

- ^ a b Spanish historian ↓ A. Ballesteros Beretta: “His moment is the inconclusive Battle of Toro.(...)both sides attributed themselves the victory (...) The letters written by the King [Ferdinand] to the main cities (...) are a model of skill. (...) what a powerful description of the battle! The nebulous transforms into light, the doubtful acquires the profile of a certain triumph. The politic [Ferdinand] achieved the fruits of a discussed victory.” In Fernando el Católico, el mejor rey de España, Ejército revue , nr 16, p.56, May 1941.

- ^ a b c d ↓ Vicente Álvarez Palenzuela- La guerra civil Castellana y el enfrentamiento con Portugal (1475–1479): “That is the battle of Toro. The Portuguese army had not been exactly defeated, however, the sensation was that D. Juana's cause had completely sunk. It made sense that for the Castilians Toro was considered as the divine retribution, the compensation desired by God to compensate the terrible disaster of Aljubarrota, still alive in the Castilian memory”.

- ^ “From a strictly military point of view, the battle of Toro cannot be considered a clear victory, but only a favorable fight for [the cause of] the Catholic Monarchs. It is not its intrinsic value which causes the joyful explosion of happiness among the chroniclers, but the consequences that resulted from it... because it definitely discourages the supporters of Juana (p. 157) ...but this document [the letter sent by Ferdinand to the cities of Castile claiming victory]... does not contradict in any way the reality of the fact that a part of the Portuguese army, having defeated the Castilian right wing, remained on the field, withdrawing in the next day without opposition. Militarily, it is an uninteresting battle, but of great political relevance, and, in this sense, is entirely favorable to the Catholic Kings (p. 161)… Not a military victory, but a political victory, the battle of Toro is in itself, a decisive event…”. (p. 163). In ↓ Mata Carriazo; Luis Suárez Fernández; Fernández Álvárez – La España de los Reyes Católicos (1474-1516), Espasa-Calpe, 1969 and 1995, pp. 157, 161, 163.

- ^ ↓ Rui de Pina – Chronica de El- rei D.Affonso V... 3rd book, chapter CLXXX.

- ^ ↓ L. Suárez Fernández, Los Reyes Catolicos: La Conquista del Trono, 1989, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d ↓ Palenzuela, La guerra civil castellana y el enfrentamiento con Portugal (1475–1479), 2006.

- ^ Title warded to him by Lope de Vega in his piece The Perfect Prince, part I.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak ↓ Pulgar- Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón, chapter XLV.

- ^ a b ↓ Góis, Chronica do Principe D. Joam, chapters LXXVII and LXXVIII (description of both armies). Sometimes Góis mentions 6 divisions in the Castilian right and other times 2 big divisions, because the Castilian right wing was divided in two parts: 5 advanced battles and a rear one (as a reserve).

- ^ ↓ Góis, Chronica do Principe D. Joam, chapters LXXVII and LXXVIII.

- ^ ↓ José Mattoso (coordinator), Nova História Militar de Portugal, 1st volume, 2003, p. 382. ISBN 9724230759

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n ↓ Góis- Chronica do Principe D. Joam, chapter LXXVIII.

- ^ Castilian chronicler ↓ Pedro de Medina: “In the Portuguese left wing, where the people of the Prince of Portugal and from the Bishop of Évora were, a very cruel battle began in which the Castilians were defeated: due to the large artillery and shotgun’s bullets from the enemy, a huge number of Castilians promptly fell dead and was necessary to remove another crowd of wounded men. As for the remaining, they found a great resistance in the Portuguese since this was their strongest army’s side, as already told, and were forced to withdraw (...). Having been so easily defeated the right battle of the Castilian army; the other two attacked their respective counterparts in order to avenge the affront and losses.” in Primera y segunda parte de las Grandezas y cosas notables de España, (it was only printed in 1595 by Diego Perez de Messa, many years after Pedro de Medina’s death), Casa de Iuan Gracian, Alcalá de Henares, pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w ↓ Garcia de Resende- Vida e feitos d’El Rei D.João II, chapter XIII.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k ↓ Juan de Mariana- Historia General de España, tome V, book XXIV, chapter X, p. 299,300.

- ^ a b c d ↓ Esteban de Garibay- Compendio Historial, tome 2, Barcelona, 1628, book 18, chapter VII, p. 597.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w ↓ Rui de Pina– Chronica de El- rei D.Affonso V... 3rd book, chapter CXCI.

- ^ ↓ chronicler Garibay also says that Ferdinand left the battlefield before Cardinal Mendoza, the Duke of Alba and the Portuguese: Compendio Historial, tome 2, Barcelona, 1628, book 18, chapter VII, p. 597.

- ^ a b c d e f g ↓ Damião de Góis Chronica do Principe D. Joam, chapter LXXIX.

- ^ a b c “...the Prince of Portugal stayed with a big battle... on top of a hill... gathering many...” in ↓ Bernaldez – Historia de los Reyes Catolicos, tome I, chapter XXIII, p. 61.

- ^ a b Chivalry tradition based on the German custom of Sessio triduana, which determined that the buyer of an immobile should stay on it in the three subsequent days after the purchase to consummate the appropriation, which became by this way indisputable, in ↓ Mattoso, 2003, Nova História Militar de Portugal, 1st volume, p. 244. ISBN 9724230759

- ^ ↓ Góis adds that before leaving the battlefield, Ferdinand sent word to the Duke of Alba and Cardinal Mendoza to assume command and to do their best. When Ferdinand and those with him reached Zamora very late that night, they didn’t know "if they were winners or defeated", in Chronica do Principe D. Joam, chapter LXXVIII, p. 303.

- ^ a b c ↓ Pulgar- Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón, chapter XLVII.

- ^ a b c d ↓ Manchado, Isabel I de Castilla y la sombra de la ilegitimidad: propaganda y representación en el conflicto sucesorio (1474–1482), 2006, p.195, 196.

- ^ a b ↓ Pulgar- Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón, chapter XLVI.

- ^ ↓ Justo L. González- Historia del Cristianismo, Editorial Unilit, Miami, 1994, Tome 2, Parte II (La era de los conquistadores), p.68.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m ↓ Á. Lopes de Chaves – Livro de apontamentos (1483–1489), 1983. A Spanish translation of the text describing the battle of Toro can be found in ↓ DURO, Cesáreo Fernández- La batalla de Toro (1476). Datos y documentos para su monografía histórica, Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, tome 38, Madrid, 1901, p. 254-257.

- ^ Those nobles should plausibly be relatives or proximal to the seven captains who led the Castilian army's right wing on the battle of Toro and that were defeated and chased by the Prince’s men. In ↓ Garcia de Resende- Vida e feitos d’El Rei D.João II, chapter CLIV.

- ^ Since, as stated by ↓ Garibay himself (Compendio Historial, tome 2, book 18, chapter VII), Prince John did not come to the aid of Afonso V throughout the battle of Toro – both were always too far from each other – this Ferdinand’s sentence only makes sense with a victorious and permanently threatening Prince on the battlefield. Ferdinand’s letter reported by Spanish chronicler ↓ Garibay in Compendio Historial, tome 2, Barcelona, 1628, book 18, chapter VIII