Extreme poverty: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.2.7.1) |

|||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

This reduction in extreme poverty took place most notably in China, Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Vietnam. These five countries accounted for the alleviation of 715 million people out of extreme poverty between 1990 and 2010 – more than the global net total of roughly 700 million. This statistical oddity can be explained by the fact that the number of people living in extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa rose from 290 million to 414 million over the same period.<ref name="autogenerated1">United Nations.[http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/report-2013/mdg-report-2013-english.pdf "The Millennium Development Goals Report"], 2013.</ref> However, there have been many positive signs for extensive, global poverty reduction as well. Since 1999, the total number of extreme poor has declined by 50 million per year, on average. Moreover, in 2005, for the first time in recorded history, poverty rates began to fall in every region of the world, including Africa.<ref>Rajiv Shah.[http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/speeches/nov-21-2013-administrator-rajiv-shah-brookings-institution-ending-extreme-poverty "Remarks by Administrator Rajiv Shah at the Brookings Institution: Ending Extreme Poverty"], USAID. November 21, 2013.</ref> Although this is largely due to a change in the 2000 UN Millennium Declaration, extending the plan period backward to 1990, it was previously 1996. Changing the date took advantage of rapid population growth and a huge poverty reduction in China during the 1990s.<ref name=ohchr>{{cite web|author=Thomas Pogge |title=Poverty and Human Rights|url=http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/poverty/expert/docs/Thomas_Pogge_Summary.pdf|website=United Nations Human Rights|accessdate=6 April 2015}}</ref> |

This reduction in extreme poverty took place most notably in China, Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Vietnam. These five countries accounted for the alleviation of 715 million people out of extreme poverty between 1990 and 2010 – more than the global net total of roughly 700 million. This statistical oddity can be explained by the fact that the number of people living in extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa rose from 290 million to 414 million over the same period.<ref name="autogenerated1">United Nations.[http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/report-2013/mdg-report-2013-english.pdf "The Millennium Development Goals Report"], 2013.</ref> However, there have been many positive signs for extensive, global poverty reduction as well. Since 1999, the total number of extreme poor has declined by 50 million per year, on average. Moreover, in 2005, for the first time in recorded history, poverty rates began to fall in every region of the world, including Africa.<ref>Rajiv Shah.[http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/speeches/nov-21-2013-administrator-rajiv-shah-brookings-institution-ending-extreme-poverty "Remarks by Administrator Rajiv Shah at the Brookings Institution: Ending Extreme Poverty"], USAID. November 21, 2013.</ref> Although this is largely due to a change in the 2000 UN Millennium Declaration, extending the plan period backward to 1990, it was previously 1996. Changing the date took advantage of rapid population growth and a huge poverty reduction in China during the 1990s.<ref name=ohchr>{{cite web|author=Thomas Pogge |title=Poverty and Human Rights|url=http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/poverty/expert/docs/Thomas_Pogge_Summary.pdf|website=United Nations Human Rights|accessdate=6 April 2015}}</ref> |

||

As aforementioned, the number of people living in extreme poverty has reduced from 1.9 billion to 1.2 billion over the span of the last 20–25 years. If we remain on our current trajectory, many economists predict we could reach global "zero" by 2030-2035, thus "ending" extreme poverty. Global zero entails a world in which fewer than 3% of the global population lives in extreme poverty (projected under most optimistic scenarios to be fewer than 200 million people). This "zero" figure is set at 3% in recognition of the fact that some amount of "frictional" poverty will continue to exist, whether it is caused by political conflict or unexpected economic fluctuations, at least for the foreseeable future.<ref name="worldbank1">World Bank.[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/Resources/334934-1327948020811/8401693-1397074077765/Prosperity_for_All_Final_2014.pdf "Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty"], Spring 2014.</ref> However, the [[Brookings Institution]] notes that any projection about poverty more than a few years into the future runs the risk of being highly uncertain. This is because changes in consumption and distribution throughout the developing world over the next two decades could result in monumental shifts in global poverty, for better or worse.<ref>Laurence Chandy et al.[http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2013/04/ending%20extreme%20poverty%20chandy/the_final_countdown.pdf "The Final Countdown: Prospects for Ending Extreme Poverty"], Brookings Institution. April 2013.</ref> |

As aforementioned, the number of people living in extreme poverty has reduced from 1.9 billion to 1.2 billion over the span of the last 20–25 years. If we remain on our current trajectory, many economists predict we could reach global "zero" by 2030-2035, thus "ending" extreme poverty. Global zero entails a world in which fewer than 3% of the global population lives in extreme poverty (projected under most optimistic scenarios to be fewer than 200 million people). This "zero" figure is set at 3% in recognition of the fact that some amount of "frictional" poverty will continue to exist, whether it is caused by political conflict or unexpected economic fluctuations, at least for the foreseeable future.<ref name="worldbank1">World Bank.[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/Resources/334934-1327948020811/8401693-1397074077765/Prosperity_for_All_Final_2014.pdf "Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty"], Spring 2014.</ref> However, the [[Brookings Institution]] notes that any projection about poverty more than a few years into the future runs the risk of being highly uncertain. This is because changes in consumption and distribution throughout the developing world over the next two decades could result in monumental shifts in global poverty, for better or worse.<ref>Laurence Chandy et al.[http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2013/04/ending%20extreme%20poverty%20chandy/the_final_countdown.pdf "The Final Countdown: Prospects for Ending Extreme Poverty"] {{wayback|url=http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2013/04/ending%20extreme%20poverty%20chandy/the_final_countdown.pdf |date=20150228203206 }}, Brookings Institution. April 2013.</ref> |

||

Others are more pessimistic about this possibility, with many predicting a range of 193 million to 660 million people living in extreme poverty by 2035. Additionally, some believe the rate of poverty reduction will slow down in the developing world, especially in Africa, and as such it will take closer to five decades to reach global "zero."<ref>Alex Thier.[http://blog.usaid.gov/2013/11/global-effort-to-end-extreme-poverty/ "A Global Effort to End Extreme Poverty"], USAID. November 22, 2013.</ref> Despite these reservations, several prominent international and national organizations, including the UN, the World Bank and the United States Federal Government (via USAID), have set a target of reaching global zero by the end of 2030. |

Others are more pessimistic about this possibility, with many predicting a range of 193 million to 660 million people living in extreme poverty by 2035. Additionally, some believe the rate of poverty reduction will slow down in the developing world, especially in Africa, and as such it will take closer to five decades to reach global "zero."<ref>Alex Thier.[http://blog.usaid.gov/2013/11/global-effort-to-end-extreme-poverty/ "A Global Effort to End Extreme Poverty"], USAID. November 22, 2013.</ref> Despite these reservations, several prominent international and national organizations, including the UN, the World Bank and the United States Federal Government (via USAID), have set a target of reaching global zero by the end of 2030. |

||

Revision as of 10:27, 28 December 2016

Extreme poverty, absolute poverty, destitution or penury, was originally defined by the United Nations in 1995 as "a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only on income but also on access to services."[2] In 2008, "extreme poverty" widely refers to earning below the international poverty line of $1.25/day (in 2005 prices), set by the World Bank. This measure is the equivalent to earning $1.00 a day in 1996 US prices, hence the widely used expression, living on "less than a dollar a day."[3] The vast majority of those in extreme poverty – 96% – reside in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, The West Indies, East Asia and the Pacific; nearly half live in India and China alone.[4]

The reduction of extreme poverty and hunger was the first Millennium Development Goal (MDG1), as set by 189 United Nations Member States in 2000. Specifically, MDG1 set a target of reducing the extreme poverty rate in half by 2015, a goal that was met 5 years ahead of schedule. This goal was created to end poverty in all its forms everywhere, and the international community, including the UN, the World Bank and the United States, has set a target of ending extreme poverty by 2030.

Defining extreme poverty

Income-based definition

Extreme poverty is defined by the International Community as earning less than a $1.25 a day, as measured in 2005 international prices. Originally, the international poverty line was set at earning a $1 a day when the Millennium Development Goals were first published. However, in 2008, the World Bank pushed the line to $1.25 to recognize higher price levels in several developing countries than previously estimated.

As of September 2010 (the most recent, reliable date), according to the UN, roughly 1.2 billion people remain in extreme poverty based on this metric.[5] Despite the significant number of individuals still earning below the international poverty line, this figure represents significant progress for the international community, as this number is 700 million fewer than the number living in extreme poverty in 1990 – 1.9 billion.[6] As highlighted in the next section, though there are many criticisms of a purely income-based approach to measuring extreme poverty, the $1.25/day line remains the most widely used metric as it is easily accessible to the public at large and "draws attention to those in the direst need."[4]

On September 23, 2015 the UK-based Financial Times reported that the World Bank intends to revise its income-based benchmark upward, to $1.90 a day.[7] As a result, poverty numbers are likely to swell, according to the paper.

Common criticism/alternatives

Though widely used by most international organizations, the $1.25/day extreme poverty line has come under scrutiny from a variety of factors. For example, when used to measure headcount ratio (i.e. the percentage of people living below the line), the $1.25/day line is unable to capture other important measures such as depth of poverty, relative poverty and how people view their own financial situation (known as the "socially subjective poverty line").[8] Moreover, the calculation of the poverty line relies on several debatable assumptions about purchasing power parity, homogeneity of household size and makeup, and consumer prices used to determine a basket of essential goods. Not to mention the fact that there may be missing data from the poorest and most fragile countries which may muddle the picture even further.

To address these problems, several alternative instruments for measuring extreme poverty have been suggested which incorporate other factors such as malnutrition and lack of access to a basic education. Thus, the 2010 Human Development Report introduced the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which measures not only income, but also basic needs. Using this tool, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimated that roughly 1.5 billion people remained in extreme poverty as opposed to the conventional figure of 1.2 billion.[9] As this figure is considered more "holistic," it may shed new light on relative deprivation within a country. For example, in Ethiopia, 39% of the population is considered extremely poor under conventional measures, but 90% are in multidimensional poverty.[10]

Another version of the MPI, known as the Alkire-Foster Method, created by Sabina Alkire and James Foster of the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), can be broken down to reflect both the incidence and the intensity of poverty. This tool is useful as development officials, using the "M0 measure" of the method (which is calculated by multiplying "the proportion of people who are poor by the percentage of dimensions in which they are deprived"), can determine the most likely causes of poverty within a region.[11] For example, in the Gaza Strip of Palestine, using the M0 measure of the Alkire-Foster method reveals that poverty in the region is primarily caused by a lack of access to electricity and drinking water, in addition to widespread overcrowding. In contrast, data from the Chhukha District of Bhutan reveals that income is a much larger contributor to poverty as opposed to other dimensions within the region.[12]

Current trends

Getting to zero

Using the World Bank definition of $1.25/day, as of September 2013, roughly 1.3 billion people remain in extreme poverty. Nearly half live in India and China, with more than 85% living in just 20 countries. Since the mid-1990s, there has been a steady decline in both the worldwide poverty rate and the total number of extreme poor. In 1990, the percentage of the global population living in extreme poverty was 43.1%, but in 2011, that percentage had dropped down to 20.6%.[4] This halving of the extreme poverty rate falls in line with the first millennium development goal (MDG1) proposed by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, who called on the international community at the turn of the century to "halv[e] the proportion of people living in extreme poverty…by 2015."[13]

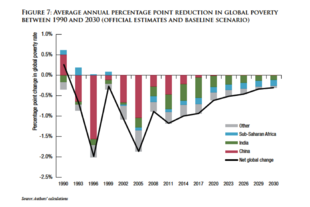

This reduction in extreme poverty took place most notably in China, Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Vietnam. These five countries accounted for the alleviation of 715 million people out of extreme poverty between 1990 and 2010 – more than the global net total of roughly 700 million. This statistical oddity can be explained by the fact that the number of people living in extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa rose from 290 million to 414 million over the same period.[14] However, there have been many positive signs for extensive, global poverty reduction as well. Since 1999, the total number of extreme poor has declined by 50 million per year, on average. Moreover, in 2005, for the first time in recorded history, poverty rates began to fall in every region of the world, including Africa.[15] Although this is largely due to a change in the 2000 UN Millennium Declaration, extending the plan period backward to 1990, it was previously 1996. Changing the date took advantage of rapid population growth and a huge poverty reduction in China during the 1990s.[16]

As aforementioned, the number of people living in extreme poverty has reduced from 1.9 billion to 1.2 billion over the span of the last 20–25 years. If we remain on our current trajectory, many economists predict we could reach global "zero" by 2030-2035, thus "ending" extreme poverty. Global zero entails a world in which fewer than 3% of the global population lives in extreme poverty (projected under most optimistic scenarios to be fewer than 200 million people). This "zero" figure is set at 3% in recognition of the fact that some amount of "frictional" poverty will continue to exist, whether it is caused by political conflict or unexpected economic fluctuations, at least for the foreseeable future.[17] However, the Brookings Institution notes that any projection about poverty more than a few years into the future runs the risk of being highly uncertain. This is because changes in consumption and distribution throughout the developing world over the next two decades could result in monumental shifts in global poverty, for better or worse.[18]

Others are more pessimistic about this possibility, with many predicting a range of 193 million to 660 million people living in extreme poverty by 2035. Additionally, some believe the rate of poverty reduction will slow down in the developing world, especially in Africa, and as such it will take closer to five decades to reach global "zero."[19] Despite these reservations, several prominent international and national organizations, including the UN, the World Bank and the United States Federal Government (via USAID), have set a target of reaching global zero by the end of 2030.

Exacerbating factors

There are a variety of factors that may reinforce or instigate the existence of extreme poverty, such as weak institutions, cycles of violence and a low level of growth. Recent World Bank research shows that some countries can get caught in a "fragility trap," in which the above factors prevent the poorest nations from emerging from low-level equilibrium in the long run.[20] Moreover, most of the reduction in extreme poverty over the past twenty years has taken place in countries that have not experienced a civil conflict or have had governing institutions with a strong capacity to actually govern. Thus, to end extreme poverty, it is also important to focus on the interrelated problems of fragility and conflict.

USAID defines fragility as a government's lack of both legitimacy (the perception the government is adequate at doing its job) and effectiveness (how good the government is at maintaining law and order, in an equitable manner). As fragile nations are unable to equitably and effectively perform the functions of a state, these countries are much more prone to violent unrest and mass inequality. Additionally, in countries with high levels of inequality (a common problem in countries with inadequate governing institutions), much higher growth rates are needed to reduce the rate of poverty when compared with other nations. Not to mention, after removing China and India from the equation, up to 70% of the world's poor live in fragile states by some definitions of fragility. Looking further, some analysts project extreme poverty will be increasingly concentrated in fragile, low-income states like Haiti, Yemen and the Central African Republic over the coming years.[21] However, some academics, such as Andy Sumner, assert that extreme poverty will be increasingly found concentrated in Middle Income Countries, creating a "poverty paradox"—as the World's poor don't actually live in the poorest countries.[22]

Despite this debate, addressing the problem of fragility remains a very real issue. To help low-income, fragile states make the transition towards peace and prosperity, the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, endorsed by roughly forty countries and multilateral institutions, was created in 2011. This "New Deal," represents an important step towards redressing the problem of fragility as it was originally articulated by self-identified fragile states who called on the international community to not only "do things differently," but to also "do different things."[23]

On the other hand, civil conflict also remains a prime cause for the perpetuation of poverty throughout the developing world. Armed conflict can have severe effects on economic growth for a plethora of reasons – it destroys assets, creates unwanted mass migration, destroys livelihoods and diverts public resources towards war fighting.[23] Significantly, a country that experienced major violence during 1981-2005 had extreme poverty rates 21 percentage points higher than a country with no violence. On average, a civil conflict will also cost a country roughly 30 years of GDP growth.[20] Therefore, a renewed commitment from the international community to address the deteriorating situation in highly fragile states is necessary to both prevent the mass loss of life, but to also prevent the vicious cycle of extreme poverty.

In 2013, a prevalent finding in a report by the The World Bank was that extreme poverty is most prevalent in what they call low income countries. In these countries the World Bank found that progress in poverty reduction is slowest, the poor live under terrible conditions and the most affected persons are children aging 12 and under.[24]

International conferences

Millennium Summit

On September 6-8th, 2000, world leaders gathered at the Millennium Summit held in New York, launching the United Nations Millennium Project suggested by then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Prior to the launch of the conference, the office of Secretary-General Annan released a report entitled We The Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century. In this document, now widely known as the Millennium Report, Kofi Annan called on the international community "to adopt the target of halving the proportion of people living in extreme poverty, and so lifting more than 1 billion people out of it, by 2015." Citing studies that show "an almost perfect correlation between growth and poverty reduction in poor countries," Annan urged international leaders to indiscriminately target the problem of extreme poverty across every region.[13] In charge of managing the project was Jeffrey Sachs, a noted development economist, who in 2005 released a plan for action called "Investing in Development: A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals."[25]

2005 World Summit

The 2005 World Summit, held on September 14-16th, was organized to measure international progress towards fulfilling the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Notably, the conference brought together more than 170 Heads of State. While world leaders at the summit were encouraged by the reduction of poverty in some nations, they were concerned by the uneven decline of poverty within and among different regions of the globe. However, at the end of the summit, the conference attendees reaffirmed the UN's commitment to achieve the MDGs by 2015 and urged all supranational, national and non-governmental organizations to follow suit.

Post-2015 Development Agenda

With the expiration of the Millennium Development Goals approaching in 2015, the international community is focused on accelerating efforts to achieve the goals laid out in the original MDGs. Overall, there has been significant progress towards reducing extreme poverty, with the MDG 1 target of reducing extreme poverty rates by half, met "five years ahead of the 2015 deadline…700 million fewer people lived in conditions of extreme poverty in 2010 than in 1990. However, at the global level 1.2 billion people [were] still living in extreme poverty."[26] One notable exception to this trend was in Sub-Saharan Africa, the only region where the number of people living in extreme poverty rose from 290 million in 1990 to 414 million in 2010, comprising more than a third of those living in extreme poverty worldwide.[14]

With the aforementioned in mind, the UN convened a High Level Panel (HLP) of Eminent Persons, to advise on a Post-2015 Development Agenda. The HLP report, entitled A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies Through Sustainable Development, was published in May 2013. In the report, the HLP wrote that:

Ending extreme poverty is just the beginning, not the end. It is vital, but our vision must be broader: to start countries on the path of sustainable development – building on the foundations established by the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro12, and meeting a challenge that no country, developed or developing, has met so far. We recommend to the Secretary-General that deliberations on a new development agenda must be guided by the vision of eradicating extreme poverty once and for all, in the context of sustainable development.

Thus, the report determined that a central goal of the Post-Millennium Development agenda is to "eradicate extreme poverty…by 2030." However, the report also emphasized that the MDGs were not enough, as they did not "focus on the devastating effects of conflict and violence on development…the importance to development of good governance and institution…nor the need for inclusive growth..." Consequently, there now exists synergy between the policy position papers put forward by the United States (through USAID), the World Bank and the UN itself in terms of viewing fragility and a lack of good governance as exacerbating extreme poverty. However, in a departure from the views of other organizations, the commission also proposed that the UN focus not only on extreme poverty (a line drawn at $1.25), but also on a higher target, such as $2. The report notes this change could be made to reflect the fact that escaping extreme poverty is "only a start."[27]

In addition to the UN, a host of other supranational and national actors such as the European Union and the African Union have published their own positions or recommendations on what should be incorporated in the Post-2015 agenda. The European Commission's communication, published in A decent Life for all: from vision to collective action, affirmed the UN's commitment to "eradicate extreme poverty in our lifetime and put the world on a sustainable path to ensure a decent life for all by 2030." A unique vision of the report was the Commission's environmental focus (in addition to a plethora of other goals such as combating hunger and gender inequality). Specifically, the Commission argued, "long-term poverty reduction…requires inclusive and sustainable growth. Growth should create decent jobs, take place with resource efficiency and within planetary boundaries, and should support efforts to mitigate climate change."[28] The African Union's report, entitled Common African Position (CAP) on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, likewise encouraged the international community to focus on eradicating the twin problems of "poverty and exclusion" in our lifetime. Moreover, the CAP pledged that it would "commit to ensure that no person – regardless of ethnicity, gender, geography, disability, race or other status – is denied universal human rights and basic economic opportunities."[29]

UN LDC conferences

The UN Least Developed Country (LDC) conferences were a series of summits organized by the UN over the past few decades, which sought to promote the substantial and even development of so-called "third-world" countries.

1st UN LDC Conference

Held between September 1 and September 14, 1981, in Paris, the first UN LDC Conference was organized to finalize the UN's "Substantial New Programme of Action" for the 1980s in Least Developed Countries. This program, which was unanimously adopted by the conference attendees, argued for internal reforms in LDCs (meant to encourage economic growth) to be complemented by strong international measures. However, despite the major economic and policy reforms initiated many of these LDCs, in addition to strong international aid, the economic situation of these countries worsened as a whole in the 1980s. This prompted the organization of a 2nd UN LDC conference almost a decade later.

2nd UN LDC Conference

Held between September 3 and September 14, 1990, once again in Paris, the second UN LDC Conference was convened to measure the progress made by the LDCs towards fulfilling their development goals during the 1980s. Recognizing the problems that plagued the LDCs over the past decade, the conference formulated a new set of national and international policies to accelerate the growth rates of the poorest nations. These new principles were embodied in the "Paris Declaration and Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the 1990s."[30]

4th UN LDC Conference

The most recent conference, held in May 2011 in Istanbul, recognized that the nature of development had fundamentally changed since the 1st conference held almost 30 years earlier. In the 21st century, the capital flow into emerging economies has increasingly become dominated by foreign direct investment and remittances, as opposed to bilateral and multilateral assistance. Moreover, since the 80s, significant structural changes have taken place on the international stage. With the creation of the G-20 conference of the largest economic powers, including many nations in the Global South, formerly "undeveloped" nations are now able to have a much larger say in international relations. Furthermore, the conference recognized that in the midst of a deep global recession, coupled with multiple crises (energy, climate, food, etc.), the international community would have fewer resources to aid the LDCs. Thus, the UN considered the participation of a wide range of stakeholders (not least the LDCs themselves), crucial to the formulation of the conference.

Organizations working to end extreme poverty

International organizations

World Bank

In 2013, the Board of Governors of the World Bank Group (WBG) set two overriding goals for the WBG to commit itself to in the future. First, to end extreme poverty by 2030, an objective that echoes the sentiments of the UN and the Obama administration. Additionally, the WBG set an interim target of reducing extreme poverty to below 9 percent by 2020. Second, to focus on growth among the bottom 40 percent of people, as opposed to standard GDP growth. This commitment ensures that the growth of the developing world lifts people out of poverty, rather than exacerbating inequality.[17]

As the World Bank's primary focus is on delivering economic growth to enable equitable prosperity, its developments programs are primarily commercial-based in nature, as opposed to the UN. Since the World Bank recognizes better jobs will result in higher income and thus, less poverty, the WBG seeks to support employment training initiatives, small business development programs and strong labor protection laws. However, since much of the growth in the developing world has been inequitable, the World Bank has also begun teaming with client states to map out trends in inequality and to propose public policy changes that can level the playing field.[31]

Moreover, the World Bank engages in a variety of nutritional, transfer payments and transport-based initiatives. Children who experience under-nutrition from conception to two years of age have a much higher risk of physical and mental disability. Thus, they are often trapped in poverty and are unable to make a full contribution to the social and economic development of their communities as adults. The WBG estimates that as much as 3% of GDP can be lost as a result of under-nutrition among the poorest nations. To combat undernutrition, the WBG has partnered with UNICEF and the WHO to ensure all small children are fully fed. The WBG also offers conditional cash transfers to poor households who meet certain requirements such as maintaining children's healthcare or ensuring school attendance. Finally, the WBG understands investment in public transportation and better roads is key to breaking rural isolation, improving access to healthcare and providing better job opportunities for the World's poor.[32]

UN

1. OCHA (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs)

The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) of the United Nations works to synchronize the disparate international, national and non-governmental efforts to contest poverty. The OCHA seeks to prevent "confusion" in relief operations and to ensure that the humanitarian response to disaster situations has greater accountability and predictability. To do so, OCHA has begun deploying Humanitarian Coordinators and Country Teams to provide a solid architecture for the international community to work through.[33]

2. UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund)

The United Nation's Children's Fund (UNICEF) was created by the UN to provide food, clothing and healthcare to European children facing famine and disease in the immediate aftermath of World War II. After the UN General Assembly extended UNICEF's mandate indefinitely in 1953, it actively worked to help children in extreme poverty in more than 190 countries and territories to overcome the obstacles that poverty, violence, disease and discrimination place in a child's path. Its current focus areas are 1) Child survival & development 2) Basic education & gender equality 3) Children and HIV/AIDS and 4) Child protection.[34]

3. UNHCR (The UN Refugee Agency)

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) is mandated to lead and coordinate international action to protect refugees worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights of refugees by ensuring anyone can exercise the right to seek asylum in another state, with the option to return home voluntarily, integrate locally or resettle in a third country. The UNHCR operates in over 125 countries, helping approximately 33.9 million persons.[35]

4. WFP (World Food Program)

The World Food Program (WFP) is the largest agency dedicated to fighting hunger worldwide. On average, WFP brings food assistance to more than 90 million people in 75 countries. The WFP not only strives to prevent hunger in the present, but also in the future by developing stronger communities which will make food even more secure on their own. The WFP has a range of expertise from Food Security Analysis, Nutrition, Food Procurement and Logistics.[36]

5. WHO (World Health Organization)

The World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for providing leadership on global health matters, shaping the health research agenda, articulating evidence-based policy decisions and combating diseases that are induced from poverty, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Moreover, the WHO deals with pressing issues ranging from managing water safety, to dealing with maternal and newborn health.[37]

Bilateral organizations

USAID

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is the lead U.S. government agency dedicated to ending extreme poverty. Currently the largest bilateral donor in the world, the United States channels the majority of its "development" assistance through USAID and the U.S. Department of State. In President Obama's 2013 State of the Union address, he declared "So the United States will join with our allies to eradicate such extreme poverty in the next two decades...which is within our reach." In response to Obama's call to action, USAID has made ending extreme poverty central to its mission statement.[38] Under its New Model of Development, USAID seeks to eradicate extreme poverty through the use of innovation in science and technology, by putting a greater emphasis on evidence based decision-making, and through leveraging the ingenuity of the private sector and global citizens.[39]

A major initiative of the Obama Administration is Power Africa, which aims to bring energy to 20 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa. By reaching out to its international partners, whether commercial or public, the US has leveraged over $14 billion in outside commitments after investing only $7 billion USD of its own. To ensure that Power Africa reaches the region's poorest, the initiative engages in a transaction based approach to create systematic change. This includes expanding access to electricity to more than 20,000 additional households which already live without power.[40]

In terms of specific programming, USAID works in a variety of fields from preventing hunger, reducing HIV/AIDS, providing general health assistance and democracy assistance, as well as dealing with gender issues. To deal with food security, which affects roughly 842 million people (who go to bed hungry each night),[41] USAID coordinates the Feed the Future Initiative (FtF). FtF aims to reduce poverty and undernutrition each by 20 percent over five years. Thanks to PEPFAR and a variety of congruent actors, the incidence of AIDS and HIV, which used to ravage Africa, have reduced in scope and intensity. Through PEPFAR, the United States has ensured over five million people have received life-saving antiviral drugs, a significant proportion of the eight million people receiving treatment in relatively poor nations.[42]

In terms of general health assistance, USAID has worked to reduce maternal mortality by 30 percent, under-five child mortality by 35 percent, and has accomplished a host of other goals.[43] USAID also supports the gamut of democratic initiatives, from promoting human rights and accountable, fair governance, to supporting free and fair elections and the rule of law. In pursuit of these goals, USAID has increased global political participation by training more than 9,800 domestic election observers and providing civic education to more than 6.5 million people.[44] Since 2012, the Agency has begun integrating critical gender perspectives across all aspects of its programming to ensure all USAID initiatives work to eliminate gender disparities. To do so, USAID seeks to increase the capability of women and girls to realize their rights and determine their own life outcomes. Moreover, USAID supports additional programs to improve women's access to capital and markets, builds theirs skills in agriculture, and supports women's desire to own businesses.[45]

DfID

The Department for International Development (DfID) is the UK's lead agency for eradicating extreme poverty. To do so, DfID focuses on the creation of jobs, empowering women and rapidly responding to humanitarian emergencies.

Some specific examples of DfID projects include governance assistance, educational initiatives, and funding cutting-edge research. In 2014 alone, DfID will support "freer and fairer" elections in 13 countries. DfID will also help provide 10 million women with access to justice through strengthened judicial systems and will help 40 million people make their authorities more accountable. By 2015, DfID will have helped 9 million children attend primary school, at least half of which will be girls.[46] Furthermore, through the Research4Development (R4D) project, DfID has funded over 35,000 projects in the name of creating new technologies to help the world's poorest. These technologies include: vaccines for diseases of African cattle, better diagnostic measures for TB, new drugs for combating malaria, and developing flood-resistant rice. In addition to technological research, the R4D is also used to fund projects that look to understand what specifically about governance structure's can be tweaked to help the world's poorest.[47]

Non-governmental movements

NGOs

A multitude of non-governmental organizations operate in the field of extreme poverty, actively working to alleviate the poorest of the poor of their deprivation. To name but a few notable organizations: Save the Children, The Overseas Development Institute, Concern Worldwide, ONE, and trickleUP have all done a considerable amount of work in extreme poverty.

Save the Children is the leading international organization dedicated to helping the World's indigent children. In 2013 alone, Save the Children reached over 143 million children through their work, including over 52 million children directly.[48] Save the Children also recently released their own report titled "Getting to Zero",[49] in which they argued the international community could feasibly do more than lift the world's poor above $1.25/day. The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the premier UK based think tank on international development and humanitarian issues. ODI is dedicated to alleviating the suffering of the world's poor by providing high-quality research and practical policy advice to the World's development officials.[50] ODI also recently released a paper entitled, "The Chronic Poverty Report 2014-2015: The road to zero extreme poverty]",[51] in which its authors assert that though the international communities' goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030 is laudable, much more targeted resources will be necessary to reach said target. The report states that "To eradicate extreme poverty, massive global investment is required in social assistance, education and pro-poorest economic growth".[52]

Concern Worldwide is an international humanitarian organization whose mission is to end extreme poverty by influencing decision makers at all levels of government (local -> international).[53] Concern has also produced a report on extreme poverty in which they explain their own conception of extreme poverty from a NGO's standpoint. In this paper, named "How Concern Understands Extreme Poverty]",[54] the report's creators write that extreme poverty entails more than just living under $1.25/day, it also includes having a small number of assets and being vulnerable to severe negative shocks (whether natural or man made).

ONE, the organization confounded by Bono, is a non-profit organization funded almost entirely by foundations, individual philanthropists and corporations. ONE's goals include raising public awareness and working with political leaders to fight preventable diseases, increase government accountability and increase investment in nutrition.[55] Finally, trickleUp is a microenterprise development program targeted at those living under a $1.25/day, which provides the indigent with resources to build a sustainable livelihood through both direct financing and considerable training efforts.[56]

Another NGO that works to end extreme poverty is Oxfam. This non-governmental organization works prominently in Africa and their mission is to improve local community organizations and works to reduce issues related to the development of the country. Oxfam helps families suffering from poverty receive food and healthcare to survive. There are many children in Africa experiencing growth stunting, and this is one example of an issue that Oxfam targets and aims to resolve.[57]

Campaigns

See also

- List of countries by percentage of population living in poverty

- Income inequality metrics

- Least developed country

- Poverty line

- Poverty reduction

- Millennium Development Goals

References

- ^ a b Laurence Chandy and Homi Kharas (2014), What Do New Price Data Mean for the Goal of Ending Extreme Poverty?, Brookings Institution, Washington DC. This article was reviewed in The Financial Times: Shawn Donnan (May 9, 2014), World Bank eyes biggest global poverty line increase in decades

- ^ United Nations. "Report of the World Summit for Social Development", March 6–12, 1995.

- ^ Martin Ravallion, Shaohua Chen & Prem Sangraula (May 2008) (PDF), Dollar a Day Revisited (Report). Washington DC: The World Bank. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "Getting to Zero: USAID Discussion Paper", November 21st, 2013.

- ^ UN MDG Factsheet."We Can End Poverty 2015", September 20–22, 2010.

- ^ USAID. "End Extreme Poverty" Last Updated: July 2nd, 2014.

- ^ FT. "Planet’s poor set to swell as World Bank moves poverty line" Last Updated: September 23, 2015.

- ^ Martin Ravallion (February 2012). "Poor, or Just Feeling Poor?" (PDF). The World Bank Open Knowledge Repository.

- ^ United Nations Development Programme."Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)". Retrieved on 17 January 2014.

- ^ Dan Morrell."Who Is Poor?", Harvard Magazine. January–February 2011.

- ^ OPHI."Alkire-Foster Method", 2014.

- ^ Sabina Alkire and James Foster."Counting and Multidimensional Poverty", International Food Policy Research Institute.

- ^ a b Kofi A. Annan (2000). We The Peoples: the Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century (PDF). United Nations. ISBN 92-1-100844-1.

- ^ a b United Nations."The Millennium Development Goals Report", 2013.

- ^ Rajiv Shah."Remarks by Administrator Rajiv Shah at the Brookings Institution: Ending Extreme Poverty", USAID. November 21, 2013.

- ^ Thomas Pogge. "Poverty and Human Rights" (PDF). United Nations Human Rights. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ a b World Bank."Prosperity for All: Ending Extreme Poverty", Spring 2014.

- ^ Laurence Chandy et al."The Final Countdown: Prospects for Ending Extreme Poverty" Archived 2015-02-28 at the Wayback Machine, Brookings Institution. April 2013.

- ^ Alex Thier."A Global Effort to End Extreme Poverty", USAID. November 22, 2013.

- ^ a b World Bank."Stop Conflict, Reduce Fragility and End Poverty: Doing Things Differently in Fragile and Conflict-affected Situations", 2013.

- ^ Nancy Lindborg."To End Extreme Poverty, Tackle Fragility", USAID. February 13, 2014.

- ^ Andy Summer."Where Will the World's Poor Live? An Update on Global Poverty and the New Bottom Billion", Center for Global Development. September 2012.

- ^ a b USAID."Ending Extreme Poverty in fragile contexts", January 28, 2014.

- ^ Olinto, Pedro, et al. "The State of the Poor: Where Are The Poor, Where Is Extreme Poverty Harder to End, and What Is the Current Profile of the World’s Poor?." Economic Premise 125.2 (2013).

- ^ Jeffrey Sachs. "Investing in Development: A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals", United Nations. 2005.

- ^ United Nations. "Goal 1: Eradicate Extreme Poverty & Hunger", 2014.

- ^ High Level Panel of Eminent Persons. "A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies Through Sustainable Development", United Nations. 2013.

- ^ "A Decent Life for All: From Vision to Collective Action" (PDF). European Commission. February 6, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014.

- ^ African Union. "Common African Position (CAP) on the Post-2015 Development Agenda", 2014.

- ^ United Nations. "Paris Declaration and Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the 1900s", 1992.

- ^ World Bank. "Poverty Overview", 2014.

- ^ World Bank. "Poverty Reduction in Practice: How and Where We Work", February 19, 2013.

- ^ "OCHA - Coordination Saves Lives". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ page author. "UNICEF - Children's Rights & Emergency Relief Organization". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "UNHCR Welcome". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "WFP - United Nations World Food Programme - Fighting Hunger Worldwide". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "WHO - World Health Organization". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ USAID. "Mission Statement", 2014.

- ^ USAID. "Annual Letter", 2014.

- ^ USAID. "Power Africa", 2014.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "The State of Food Insecurity in the World", 2013.

- ^ USAID. "End Extreme Poverty", 2014.

- ^ USAID. "What We Do: Global Health", 2014.

- ^ USAID. "What We Do: Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance", 2014.

- ^ USAID. "What We Do: Fostering Women's Leadership", 2014.

- ^ "About - Department for International Development - GOV.UK". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ DfID. "Research at DfID"

- ^ "Save the Children". Save the Children International. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Getting to Zero" (PDF). Save the Children. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "About ODI". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ The Chronic Poverty Report 2014-2015: The road to zero extreme poverty

- ^ Andrew Shepherd; Lucy Scott; Chiara Mariotti; Flora Kessy; Raghav Gaiha; Lucia da Corta; Katharina Hanifnia; Nidhi aicker; Amanda Lenhardt; Charles Lwanga-Ntale; Binayak Sen; Bandita Sijapati; Tim Strawson; Ganesh Thapa; Helen Underhill; Leni Wild (2015). Chronic Poverty Report 2014–15: The Road to Zero Extreme Poverty. Overseas Development Institute.

- ^ "About Concern". Concern Worldwide. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ How Concern Understands Extreme Poverty

- ^ One International. "About"

- ^ Trickle Up. "Our Approach"

- ^ https://www.oxfam.org/en/countries/south-africa

External links

- Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger by 2015 | UN Millennium Development Goal curated by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Michigan State University

- The Life You Can Save - Acting Now to End World Poverty

- WhiteBand.org - Global Call to Action Against Poverty

- Half The Sky

- Scientific American Magazine (September 2005 Issue) Can Extreme Poverty Be Eliminated?

- International Movement ATD Fourth World

- Walk In Her Shoes