Fear of Flying (novel): Difference between revisions

Opencooper (talk | contribs) m →External links: inline |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.5.4) |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

{{reflist|refs= |

{{reflist|refs= |

||

<ref name="bbc">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/womanshour/wwf_fear_of_flying.shtml |publisher=[[BBC Radio 4]] |work=[[Woman's Hour]] |title=''Fear of Flying'' (1973) by Erica Jong |accessdate=January 23, 2010}}</ref> |

<ref name="bbc">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/womanshour/wwf_fear_of_flying.shtml |publisher=[[BBC Radio 4]] |work=[[Woman's Hour]] |title=''Fear of Flying'' (1973) by Erica Jong |accessdate=January 23, 2010}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="penguin">{{cite web|url=http://us.penguingroup.com/static/rguides/us/fear_of_flying.html |work=Penguin Reading Guides |title=''Fear of Flying'' – Erica Jong |publisher=[[Penguin Books]] |accessdate=January 23, 2010}}</ref> |

<ref name="penguin">{{cite web |url=http://us.penguingroup.com/static/rguides/us/fear_of_flying.html |work=Penguin Reading Guides |title=''Fear of Flying'' – Erica Jong |publisher=[[Penguin Books]] |accessdate=January 23, 2010 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100114012553/http://us.penguingroup.com/static/rguides/us/fear_of_flying.html |archivedate=January 14, 2010 |df= }}</ref> |

||

<ref name="newyorker">{{cite web|url=http://www.newyorker.com/talk/2008/04/14/080414ta_talk_mead |title=The Canon: Still Flying |work=[[The New Yorker]] |first=Rebecca |last=Mead |date=April 14, 2008 |accessdate=January 23, 2010}}</ref> |

<ref name="newyorker">{{cite web|url=http://www.newyorker.com/talk/2008/04/14/080414ta_talk_mead |title=The Canon: Still Flying |work=[[The New Yorker]] |first=Rebecca |last=Mead |date=April 14, 2008 |accessdate=January 23, 2010}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=salon>{{cite web |url=http://archive.salon.com/sex/feature/2003/06/14/jong/index_np.html |date=June 14, 2003 |title=The 'Sex Woman' |first=David |last=Bowman |accessdate=January 23, 2010 |work=[[Salon (website)|Salon]]}}</ref> |

<ref name=salon>{{cite web |url=http://archive.salon.com/sex/feature/2003/06/14/jong/index_np.html |date=June 14, 2003 |title=The 'Sex Woman' |first=David |last=Bowman |accessdate=January 23, 2010 |work=[[Salon (website)|Salon]] |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070706022344/http://archive.salon.com/sex/feature/2003/06/14/jong/index_np.html |archivedate=July 6, 2007 |df= }}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 01:29, 29 September 2017

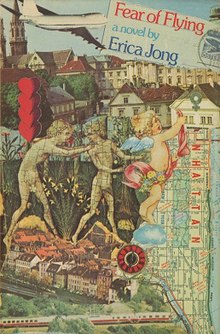

First edition cover | |

| Author | Erica Jong |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Judith Seifer |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Holt, Rinehart and Winston |

Publication date | 1973 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 340 pp |

| ISBN | 0-03-010731-8 |

| OCLC | 618357 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.J812 Fe PS3560.O56 |

| Followed by | How to Save Your Own Life |

Fear of Flying is a 1973 novel by Erica Jong, which became famously controversial for its portrayal of female sexuality, figured in the development of second-wave feminism.

The novel is written in the first person: narrated by its protagonist, Isadora Zelda White Stollerman Wing, a 29-year-old poet who has published two books of poetry. On a trip to Vienna with her second husband, Isadora decides to indulge her sexual fantasies with another man. Its tone may be considered conversational or informal. The story's American narrator is struggling to find her place in the world of academia, feminist scholarship, and in the literary world as a whole. The narrator is a female author of erotic poetry, which she publishes without fully realizing how much attention she will attract from both critics and writers of alarming fan letters.

The book resonated with women who felt stuck in unfulfilled marriages,[1] and it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide.

Jong has denied that the novel is autobiographical but admits that it has autobiographical elements.[2] However, an article in The New Yorker recounts that Jong's sister, Suzanna Daou (née Mann), identified herself at a 2008 conference as the reluctant model for Isadora Wing, calling the book "an exposé of my life when I was living in Lebanon". Daou angrily denounced the book, linking its characters to people in her own life and taking her sister to task for taking cruel liberties with them, especially Daou's husband. In the book, Isadora Wing's sister Randy is married to Pierre, who makes a pass at both Wing and her two other sisters. Jong dismissed her sister's claim, saying instead that "every intelligent family has an insane member".[3]

The zipless fuck

It was in this novel that Erica Jong coined the term "zipless fuck", which soon entered the popular lexicon.[4] A "zipless fuck" is defined as a sexual encounter for its own sake, without emotional involvement or commitment or any ulterior motive, between two previously unacquainted persons.

The zipless fuck is absolutely pure. It is free of ulterior motives. There is no power game. The man is not "taking" and the woman is not "giving". No one is attempting to cuckold a husband or humiliate a wife. No one is trying to prove anything or get anything out of anyone. The zipless fuck is the purest thing there is. And it is rarer than the unicorn. And I have never had one.

— Erica Jong, Fear of Flying (1973)

Jong goes on to explain that it is "zipless" because "when you came together, zippers fell away like rose petals, underwear blew off in one breath like dandelion fluff. For the true ultimate zipless A-1 fuck, it was necessary that you never got to know the man very well."

The story

The novel begins on an airplane flight to Vienna, where the narrator is headed to attend a psychoanalytic conference of mostly Freudian analysts. (The opening sentence memorably reads, "There were 117 psychoanalysts on the Pan Am flight to Vienna and I'd been treated by at least six of them.") It seems the narrator might feel anxious on airplanes, in a time of both civil unrest and fear of foreign terrorism. The narrator is both literate and well educated enough to have been reading newspaper accounts of attempted and completed airline hijackings. Freudians perhaps inevitably have their own ideas about the symbolism of an airplane in the formation of the unconscious and the sexual psyche, and this contrast provides narrative suspense. What did the six psychiatrists make of the narrator's fears? Did she tell them? What will they say in Vienna if she mentions her nervous emotions? These questions are not really explicitly stated, but they may well occur to a reader's mind. The narrator, meanwhile, occupies her mind with many questions, plans, mental rough drafts and reminiscences as her journey unfolds.

But still the "zipless fuck", a major motif in the story, haunts the novel's narrator as she travels. Eventually she reaches both solid land and even her proper destination, Vienna. There she has a sexual adventure involving both her faithful male companion Bennett and a fling, Adrian. Then it is time to depart, and after she has said goodbye to her casual lover (giving him her real New York address and telephone number, confident in her hunch that this particular man will likely just lose it anyway), the reader finds her seated in a cafe, with suitcase, feeling "like a fraud" and wondering, "Why wasn't I grateful for being hunted?" At the parting, she had felt as though there were "nothing but a slim volume of verse between me and the void". In the cafe, she muses:

But now I wanted to be alone, and if anybody interpreted my behavior differently, I'd react like a wild beast. Even Bennett, with all his supposed psychology and insight, maintained that men tried to pick me up all the time because I conveyed my "availability"—as he put it. Because I dressed too sexily. Or wore my hair too wantonly. Or something. I deserved to be attacked, in short. It was the same old jargon of the war between the sexes, the same old fifties lingo in disguise: There is no such thing as rape; you ladies ask for it. You ladies.

— Erica Jong, Fear of Flying (1973)

The last leg of the narrator's return trip must be by train, as she wishes to get from Paris to Great Britain, where she will meet up with Bennett again. As she is trying to swing her suitcase into the overhead train compartment, a young attendant wearing a blue uniform walks up and takes her suitcase from her. She thanks him, and reaches for her purse, but this supposedly universal gesture indicating "tip" seems foreign to him; he walks away. "You will be alone?" he [asks] ambiguously. He begins to pull down all the shades and to convert the compartment into a sleeper. At least, he runs his hands along the seats and the narrator assumes a linguistic gap and supplies reasons for his gestures within her own mind: she considers it most probable that he is just doing his train attendant job. She remarks that "this", possibly meaning all this attention, may not be fair to all the other passengers, for although she has travelled to Vienna, she is still an American, with an American code of politeness and consideration. And next:

"You are seule?" he asked again, flattening his palm on my belly and pushing me down toward the seat. Suddenly his hand was between my legs and he was trying to hold me down forcibly. "What are you doing?" I screamed, springing up and pushing him away. I knew very well what he was doing, but it had taken a few seconds to register.

— Erica Jong, Fear of Flying (1973)

The narrator does not end up being sexually assaulted; instead, she has grabbed her suitcase and fled the compartment. The train attendant merely stands and allows her to leave, smiling crookedly while shrugging. She finds another compartment, and after calming down, at last concludes her meditations upon the puzzle or conundrum that is her own personal invention, the "zipless fuck":

It wasn't until I was settled, facing a nice little family group--mother, daddy, baby--that it dawned on me how funny that episode had been. My zipless fuck! My stranger on a train! Here I'd been offered my very own fantasy. The fantasy that had riveted me to the vibrating seat of the train for three years in Heidelberg and instead of turning me on, it had revolted me!

— Erica Jong, Fear of Flying (1973)

The novel remains a feminist classic and the phrase "zipless fuck" has seen a resurgence in popularity as third-wave feminism authors and theorists continue to use it while reinterpreting their approach to sexuality and to femininity. John Updike's New Yorker review is still a helpful starting point for curious onlookers. He commented, "A sexual frankness that belongs to, and hilariously extends the tradition of The Catcher in the Rye and Portnoy's Complaint."

Film and radio adaptations

Many attempts to adapt this property for Hollywood have been made, starting with Julia Phillips, who fantasized that it would be her debut as a director. The deal fell through and Erica Jong litigated, unsuccessfully.[5] In her second novel,[6] Jong created the character Britt Goldstein—easily identifiable as Julia Phillips—a predatory and self-absorbed Hollywood producer devoid of both talent and scruples.

In May 2013 it was announced[7] that a screenplay version by Piers Ashworth had been green-lighted by Blue-Sky Media, with Laurie Collyer directing.

References

- Notes

- ^ "Fear of Flying (1973) by Erica Jong". Woman's Hour. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ "Fear of Flying – Erica Jong". Penguin Reading Guides. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mead, Rebecca (April 14, 2008). "The Canon: Still Flying". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Bowman, David (June 14, 2003). "The 'Sex Woman'". Salon. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Phillips, Julia (1991). You'll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again. Random House. pp. 136 et seq. ISBN 0-394-57574-1.

- ^ Jong, Erica (2006). How to Save Your Own Life. Tarcher. ISBN 1585424994.

- ^ Fleming, Jr, Mike (10 May 2013). "Erica Jong's Fear of Flying Getting a Movie after 40 Years in Print". Deadline.com. Retrieved February 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help)

External links

Quotations related to Fear of Flying at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Fear of Flying at Wikiquote