Cream gene: Difference between revisions

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

===Analogous conditions in other animals=== |

===Analogous conditions in other animals=== |

||

The MATP gene is highly conserved, especially among mammals. The human MATP gene is 82% identical to the mouse MATP gene, 79% identical to the rat MATP gene, 35% to the zebrafish version, and 30% identical to the fruitfly MATP gene.<ref name=liwei>{{cite web |url=http://liweilab.genetics.ac.cn/HPSD/OCA4.htm |title=Oculocutaneous Albinism 4 |work=Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome Database |author=Wei Li |date=2008-08-30}}</ref> The gene is best known in humans as being the location of a mutation that results in human type IV oculocutaneous albinism (OCA4). Type IV oculocutaneous albinism, like other types of human albinism, results in hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, with increased rates of skin cancer and reduced visual acuity.<ref name=newton2001>{{cite journal |last=Newton |first=JM |author2=Cohen-Barak O |author3=Hagiwara N |author4=Gardner JM |author5=[[Muriel Davisson|Davisson MT]] |author6=King RA |author7=Brilliant MH |title=Mutations in the Human Orthologue of the Mouse underwhite Gene (uw) Underlie a New Form of Oculocutaneous Albinism, OCA4 |journal=American Journal of Human Genetics |date=November 2001 |volume=69 |issue=5 |pages=981–8 |pmid=11574907 |pmc=1274374 |doi=10.1086/324340}}</ref> None of these effects are associated with the equine cream gene. Other human MATP polymorphisms result in normal pigment variations, specifically fair skin, light eyes, and light hair in Caucasian populations.<ref name=omim>{{OMIM|606202|Solute Carrier Family 45, Member 2; SLC45A2}}</ref> |

The MATP gene is highly conserved, especially among mammals. It can also happen in [[zebra]]s but can only occur in captivity. The human MATP gene is 82% identical to the mouse MATP gene, 79% identical to the rat MATP gene, 35% to the zebrafish version, and 30% identical to the fruitfly MATP gene.<ref name=liwei>{{cite web |url=http://liweilab.genetics.ac.cn/HPSD/OCA4.htm |title=Oculocutaneous Albinism 4 |work=Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome Database |author=Wei Li |date=2008-08-30}}</ref> The gene is best known in humans as being the location of a mutation that results in human type IV oculocutaneous albinism (OCA4). Type IV oculocutaneous albinism, like other types of human albinism, results in hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, with increased rates of skin cancer and reduced visual acuity.<ref name=newton2001>{{cite journal |last=Newton |first=JM |author2=Cohen-Barak O |author3=Hagiwara N |author4=Gardner JM |author5=[[Muriel Davisson|Davisson MT]] |author6=King RA |author7=Brilliant MH |title=Mutations in the Human Orthologue of the Mouse underwhite Gene (uw) Underlie a New Form of Oculocutaneous Albinism, OCA4 |journal=American Journal of Human Genetics |date=November 2001 |volume=69 |issue=5 |pages=981–8 |pmid=11574907 |pmc=1274374 |doi=10.1086/324340}}</ref> None of these effects are associated with the equine cream gene. Other human MATP polymorphisms result in normal pigment variations, specifically fair skin, light eyes, and light hair in Caucasian populations.<ref name=omim>{{OMIM|606202|Solute Carrier Family 45, Member 2; SLC45A2}}</ref> |

||

A polymorphism on the mouse MATP gene is known to be the cause of the ''underwhite'' coat color phenotype. The phenotype was first identified in the 1960s, and since then has been mapped successfully. Affected individuals have a reduction in eye and coat pigmentation, and irregularly shaped melanosomes.<ref name=sweet1998 /> |

A polymorphism on the mouse MATP gene is known to be the cause of the ''underwhite'' coat color phenotype. The phenotype was first identified in the 1960s, and since then has been mapped successfully. Affected individuals have a reduction in eye and coat pigmentation, and irregularly shaped melanosomes.<ref name=sweet1998 /> |

||

Revision as of 19:12, 17 May 2018

The cream gene is responsible for a number of horse coat colors. Horses that have the cream gene in addition to a base coat color that is chestnut will become palomino if they are heterozygous, having one copy of the cream gene, or cremello, if they are homozygous. Similarly, horses with a bay base coat and the cream gene will be buckskin or perlino. A black base coat with the cream gene becomes the not-always-recognized smoky black or a smoky cream. Cream horses, even those with blue eyes, are not white horses. Dilution coloring is also not related to any of the white spotting patterns.

The cream gene (CCr) is an incomplete dominant allele with a distinct dosage effect. The DNA sequence responsible for the cream colors is the cream allele, which is at a specific locus on the MATP gene. Its general effect is to lighten the coat, skin and eye colors. When one copy of the allele is present, it dilutes "red" pigment to yellow or gold, with a stronger effect on the mane and tail, but does not dilute black color to any significant degree. When two copies of the allele are present, both red and black pigments are affected; red hairs still become cream, and black hairs become reddish. A single copy of the allele has minimal impact on eye color, but when two copies are present, a horse will be blue-eyed in addition to a light coat color.

The cream gene is one of several hypomelanism or dilution genes identified in horses. Therefore, it is not always possible to tell by color alone whether the CCr allele is present without a DNA test. Other dilution genes that may mimic some of the effects of the cream gene in either single or double copies include the pearl gene, silver dapple gene, and the champagne gene. Horses with the dun gene also may mimic a single copy of the cream gene. To complicate matters further, it is possible for a horse to carry more than one type of dilution gene, sometimes giving rise to coloring that researchers call a pseudo double dilute.

The discovery of the cream gene had a significant effect on breeding, allowing homozygous blue-eyed creams to be recognized by many breed registries that had previously registered palominos but banned cremellos, under the mistaken notion that homozygous cream was a form of Albinism.

Colors produced

Cream coat colors are described by their relationship to the three "base" coat colors: chestnut, bay, and black. All horses obtain two copies of the MATP gene; one from the sire, and one from the dam. A horse may have the cream allele or the non-cream allele on each gene. Those with two non-cream alleles will not exhibit true cream traits. Horses with one cream allele and one non-cream allele, popularly called "single dilutes," exhibit specific traits: all red pigment in the coat is gold, while the black pigment is either unaffected or only subtly affected.[1][2] These horses are usually palomino, buckskin, or smoky black. These horses often have light brown eyes.[3] Horses with 2 copies of the cream allele also exhibit specific traits: cream-colored coats, pale blue eyes, and rosy-pink skin. These horses are usually called cremello, perlino, or smoky cream.

Heterozygous creams ("single dilutes")

Horses that are heterozygous creams, that is, have only one copy of the cream gene, have a lightened hair coat. The precise cream dilute coat color produced depends on the underlying base coat color. Unless also affected by other, unrelated genes, they maintain dark skin and brown eyes, though some heterozygous dilutes may be born with pink skin that darkens with age. Some have slightly lighter, amber eyes. However, the heterozygous cream dilute (CR) must not be confused with a horse carrying champagne dilution. Champagne (CH) dilutes are born with pumpkin-pink skin and blue eyes, which darken within days to amber, green or light brown, and their skin acquires a darker mottled complexion around the eyes, muzzle, and genitalia as the animal matures.[4] It is also possible for a heterozygous cream horse to carry more than one of the other dilution alleles. (see "Cream mimics," below) In such cases, they may exhibit some characteristics more typical of a homozygous dilute.

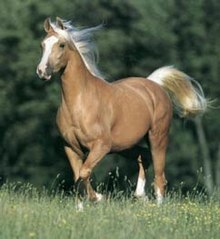

Palomino is the best known cream-based coat color, and is produced by the action of one cream allele on a chestnut coat. It is characterized by a cream or white mane and tail and yellow or gold coat.[3] The classic golden shade akin to that of a newly minted gold coin is common, but there are other variations: the darkest shades are called sooty palominos, unusual but most often seen in Morgans, can include a mane and tail with darker hairs and heavy dappling in the coat.[5] The palest varieties can be nearly white, retaining darker skin and eyes, are sometimes mistakenly confused with cremello, and are called isabellas in some places.

Buckskin is also a well-known color, produced by the action of one cream gene on a bay coat. All red hairs in the base coat are diluted to gold. The black areas, such as the mane, tail and legs, are generally unaffected. The cream gene acting on a "blood bay" coat, the reddest shade, are pale gold with black points. They are sometimes called buttermilk buckskins. The cream gene acting on the darkest bays, (sometimes mistaken for seal browns) may dilute to a sooty buckskin. True seal brown buckskins can be very difficult to identify owing to their almost all-black coats. It is only the reddish markings around the eyes, muzzle, elbow and groin, which are turned gold, that may give them away.[6]

Smoky black, a horse with a black base coat and one copy of the cream allele, is less well-known than the two golden shades. Since a single copy of the cream gene primarily affects red pigment, with only a subtle effect on black, smoky blacks can be quite difficult to identify. Smoky blacks may have reddish guard hairs inside their ears,[citation needed] and experienced horse persons may detect something "off" about the coat of a smoky black, though the slightly burnished look is often chalked up to sun bleaching, which can also be seen in true blacks. The palest can be mistaken for bays or liver chestnuts, especially if exposed to the elements. Smoky black coats tend to react strongly to sun and sweat, and many smoky blacks turn a chocolate color with particularly reddish manes and tails. Bleaching due to the elements means that the legs retain their color better, and can take on an appearance of having dark points like a bay horse. Smoky blacks, however, will lack rich red tones in the coat, instead favoring chocolate and orange tones. Because smoky blacks are often not recognized as such, breeders sometimes think that the cream gene "skipped" generations.

While there are "color breed" registries for palomino and buckskin horses, which generally record horses based on apparent phenotype and do not require a DNA color test, it is impossible for these colors to breed "true" due to the action of a single copy of the cream allele. Crossing two heterozygous dilutes will statistically result in offspring which are 25% the base color, 25% homozygous dilute, and 50% heterozygous dilute.

Homozygous creams ("double dilutes")

When a horse is homozygous, meaning it has two copies of the cream allele, the strongest color dilution occurs.

- Cremellos are homozygous cream chestnuts, and have a cream colored body with a cream or white mane and tail.

- Perlinos are homozygous cream bays, which also have a cream-colored body but a mane and tail that may be somewhat more reddish in color than a cremello.

- Smoky Creams are homozygous cream blacks, and very difficult to visually distinguish from cremellos or perlinos.

All three shades can be difficult to distinguish from one another, and are often only firmly identified after a DNA test. While both red and black pigments are turned cream, the black pigment retains a little more color and tends to have a reddish or rusty tint.[7] Thus all-red coats are turned all-ivory, all-black coats are turned all-rusty cream, and bay coats have ivory bodies with slightly darker points.[3]

Horses with two copies of the cream allele can be collectively called double-dilutes, homozygous creams, or blue-eyed creams, and they share a number of characteristics. The eyes are pale blue, paler than the unpigmented blue eyes associated with white color or white markings, and the skin is rosy-pink. The true, unpigmented pink skin associated with white markings is clearly visible against the rosy-pink skin of a double-dilute, especially when their coat is wetted down. The palest shades of double-dilute coats are just off-white, while the darkest are distinctly rust-tinged. Their coats may be described as nearly white[1] or ivory[3] in addition to cream.

The off-white coat, pale blue eyes, and rosy pink skin distinguish the coats of double-dilutes from those of true white horses. True white horses have unpigmented skin and hair due to the incomplete migration of melanocytes from the neural crest during development.[8]

No health defects are associated with the cream gene. This is also true of the normal variations in skin, hair and eye color encoded on the human MATP gene.[9] True white coat coloring can be produced by at least half a dozen known genes, and some are associated with health defects. Some genes which encode a white or near-white coat when heterozygous, popularly called "dominant white," may be lethal in homozygote embryos.[10] Another specific mutation on the endothelin receptor type B (EDNRB) gene is associated with the frame overo pattern produces Lethal white syndrome if homozygous, but carriers can be identified with a DNA test.

Prevalence

The cream gene is found in many breeds. It is common in American breeds including the American Quarter Horse,[11] Morgan,[12] American Saddlebred, Tennessee Walking Horse,[13] and Missouri Fox Trotter.[14] It is also seen in the Miniature horse,[15] Akhal-Teke,[16] Icelandic horse,[17] Connemara pony,[1] and Welsh pony.[18] It is even found in certain lines of Thoroughbreds,[19] Warmbloods, and the Lusitano.[20] The Andalusian horse has conflicting standards, with the cream gene being recognized by some registries,[20] but not explicitly mentioned by others.[21] The cream gene is completely absent from the Arabian horse genepool,[22] and is also not found in breeds with stringent color requirements, such as the Friesian horse.

Cream mimics

Other coat colors may mimic the appearance of a cream coat color. The presence or absence of the cream gene can always be verified by the use of a DNA test. Also, as explained in "Mixed dilutes," below, horses may simultaneously carry more than one dilution gene. Dilution genes which, by themselves, may be confused with cream dilutions include the following:

- Bay dun vs. Buckskin: the action of the dun gene on bay produces a buckskin-like coat. Additional confusion occurs because in some countries, it is still customary to refer to buckskins as "dun", particularly in the British pony breeds. Bay duns tend to have a flatter coat color, more tan or peanut butter-colored than bronze, and also exhibit primitive markings.

- Amber champagne vs. Buckskin: the action of the Champagne gene on bay can also produce a buckskin-like coat. Champagnes can be identified by their freckled skin, hazel eyes, and chocolate (rather than black) points.

- Flaxen chestnut vs. Palomino: Horses having light chestnut coats with flaxen manes and tails, such as those found in the Haflinger breed, can be confused with palominos. However, unlike chestnuts, palomino is inherently a heterozygous condition and thus cannot be true-breeding. Furthermore, even the lightest chestnut will retain "red" character in the hair, rather than gold.

- Gold champagne vs. Palomino: the action of the Champagne gene on chestnut was for many years called pumpkin-skinned palomino. However, lighter, freckled skin and hazel eyes identify a gold champagne, which can otherwise look much like a palomino.

- Pearl vs. Palomino: the action of the pearl gene only occurs on a red coat when the pearl allele is homozygous. In such cases, the red hairs are lightened to an apricot color.[23]

- Pseudo double-dilute vs. Cremello: A horse that has one cream allele and one pearl allele may resemble a homozygous cream, including pinkish skin and blue eyes. A combination of one cream and one Champagne allele may also produce a similar phenotype, though may be distinguishable by lighter yellowish or blue eyes and pale, faintly freckled skin.

- White vs. Double dilute: White horses with blue or dark eyes and pink skin are born white and remain so throughout life. Cremello and isabelline horses that bleach out in the sun may approach a near-white shade, but have some skin pigment, exhibited by a slightly more peach skin tone and blue-eyed creams have a less vivid shade of blue when compared to that of an unpigmented blue-eye.

- Gray vs. Double dilute: Gray horses are born a normal color and grow progressively lighter in their coat, while double-dilute creams do not. Grays that are not affected by a dilution gene do not have blue eyes or pink skin unless they are due to white markings. There are, however, records of palominos, buckskins, smoky blacks, and double-dilute creams that also carry the gray gene.[1]

Mixed dilutes

If a horse carries more than one type of dilution gene, additional cream mimics and other unique colors may occur. The combined effects of champagne and a single cream gene can be hard to distinguish from a double-dilute cream. Freckled skin and greenish eyes, or pedigree knowledge can yield clues, though the mystery can also be solved with a DNA test.

The pearl gene or "barlink factor" is a recessive gene that affects only red pigment.[2] When a single copy each of pearl and cream are present, the effect is quite similar to cremello. Dilutes combining the pearl gene with one copy of the cream gene are known as "pseudo-double dilutes" and produce a cream dilute phenotype that includes pale skin and blue/green eyes.[2] DNA tests and patience are effective in determining which is the case.

Some of the terms used to describe these combinations include:

- Dunalino, yellow dun or palomino dun: a chestnut-based coat with one cream allele and at least one dun allele. The points are reddish, but the body coat is a paler, flatter shade of gold and primitive markings are visible.

- Dunskin, buckskin dun, or buttermilk dun: a bay-based coat with one cream allele and at least one dun allele. These are quite difficult to tell apart from ordinary duns. They are a slightly paler shade, and retain their dark points and primitive markings.

- Cream dun, Cremello dun or linebacked cremello: a blue-eyed cream horse also carrying the dun gene. The primitive markings associated with the dun color are usually quite visible, especially on horses with a bay or black base coat.

- Smoky grulla, silver grulla or smoky black dun: a black-based coat with one cream allele and at least one dun allele. The effect is of an extra-pale grulla.

- Double-cream champagne: any blue-eyed cream horse that also carries the champagne gene. The champagne traits are, in the few known individuals, not visible. The skin is quite pink.

- Amber cream or Buckskin champagne: a bay-based coat with one cream allele and at least one champagne allele. The skin and eyes have champagne traits such as skin mottling, while the coat is a pale buff color. The points are a soft, pale grayish-chocolate.

- Classic cream or Smoky black champagne: a black-based coat with one cream allele and at least one champagne allele. is also an acceptable term. Like an amber cream, they retain champagne traits in the skin and eyes, and range from pale buff to pale chocolatey-gray. Even though the coat is black-based, the mane and tail tend to be darker.

- Gold cream: chestnut-based coat with one cream allele and at least one champagne allele. Formerly referred to as "ivory champagne." The champagne traits remain in the skin and eyes, and the coat is an all-over ivory color.

- Sable cream or Brown buckskin champagne: brown-based coat with one cream allele and at least one champagne allele. The coat color falls between amber and classic cream.

- Silver buckskin: bay-based coat with one cream allele and at least one silver dapple allele. The effect varies, as silver dapple does not act on red coats, but the buckskin's golden tone is somewhat lost.

- Silver smoky black: black-based coat with one cream allele and at least one silver allele. The effect varies from chestnut-like to silver black-like. Lighter eyes can help with identification.

Inheritance and expression

The cream locus is on exon 2 of the MATP gene; a single nucleotide polymorphism results in an aspartic acid-to-asparagine substitution (N153D).[1] The DNA test offered by various laboratories detects this mutation.[2] The MATP gene encodes a protein illustrated to have roles in melanogenesis in humans, mice, and medaka.[1] Mice affected by a condition homologous to cream exhibit irregularly shaped melanosomes, which are the organelles within melanocytes that directly produce pigment.[24]

Genes in horses such as Frame and Sabino1 produce white spotting by interrupting or limiting the migration of melanocytes from the neural crest, while the cream mutation affects the nature of the pigments produced by melanocytes. Therefore the skin, eyes, and hair of horses with the cream mutation do not lack melanocytes, melanosomes, or melanins, but rather exhibit hypomelanism.[1]

Prior to the mapping of the cream gene, this locus was titled C for "color".[3] There are two alleles in the series: the recessive, wildtype allele C and the incomplete dominant CCr.[2] The CCr allele represents the N153D MATP mutation.

- C/C recessive homozygotes are not affected by cream and have no true cream traits.

- C/CCr heterozygotes have one cream allele, and one wildtype non-cream allele. Only red pigment in the hair is diluted, as seen in buckskins and palominos.

- CCr/CCr homozygotes (homozygous creams) have no wildtype non-cream alleles. The red and black pigment in the hair are diluted to cream, the eyes are light blue and the skin is rosy pink.

Cream was first formally studied by Adalsteinsson in 1974, who reported that the inheritance of palomino and buckskin coat colors in Icelandic horses followed a "semi-dominant" or incomplete dominant model. Adalsteinsson also noted that in heterozygotes, only the red pigment (pheomelanin) was diluted.[17]

The discovery that the palomino coat color was inextricably linked to the cream coat color was very significant. At one time, double dilutes, particularly cremellos, were barred from registration by many breed organizations.[25] Cremello was thought by some to be a lethal white or albino coloring and a potential genetic defect.[26] There also were known health implications of albinism in humans,[27] and cultural prejudices; while a heroic figure such as Roy Rogers rode a golden palomino, the "Albino" in Mary O'Hara's Thunderhead portrayed a horse with a freakish defect. These coat colors carried vastly different cultural significance. Because the experience of breeders of palomino and buckskin horses indicated that blue-eyed cream offspring of these animals were not genetically defective, some of the research that took place nearly thirty years after Adalsteinsson's studies that identified the nature of cream dilution was directly supported by breed registries that had historically barred blue eyed creams.

Cryptic creams

The cream gene's preferential effect on red pigment has not yet been explained. The champagne dilution affects both black and red pigments equally, the silver dapple gene affects only black pigment, and pearl exhibits a recessive mode of inheritance and only affects red pigment.[2] Unlike the cream gene, pearl does not seem to affect the mane and tail to a greater extent than the body coat, a feature of cream that is most vividly illustrated in the palomino coat color. This characteristic of the cream gene is also unexplained. The disparity in effects on red and black pigments is easy to identify in buckskins, with their black points, but it is also visible in CCr/CCr homozygotes: perlinos (homozygous cream on a bay coat) often retain points that are a darker shade of cream.[3]

This unusual feature enables what are called cryptic creams.[1] A certain percentage of dark bay, seal brown, and black horses exhibit such subtle dilution of their coats as to be misregistered. In the study that mapped the cream gene, three horses registered as seal brown, dark bay or bay were actually smoky black and buckskin.[1] This is one way by which the cream gene is transmitted through generations without being identified. Horses born palomino, buckskin, and smoky black, but also carry the gray gene, have a hair coat that turns white as they age and are usually registered as "gray" rather than as their birth color. This is particularly a common occurrence in the Connemara breed. Horses sold after turning fully gray may surprise breeders by producing golden or cream offspring.[1]

This effect - stronger expression on red pigment - is also seen in coat pattern genes in horses. In general, white markings are more pervasive in chestnuts than in non-chestnuts, to the extent that homozygous non-chestnuts (which carry the "Extension" (E) gene and may also carry the Agouti gene) were more modestly marked than non-chestnuts heterozygous for the E gene.[28][29][30] This effect has also been identified and studied in the Leopard complex patterns.[31]

Analogous conditions in other animals

The MATP gene is highly conserved, especially among mammals. It can also happen in zebras but can only occur in captivity. The human MATP gene is 82% identical to the mouse MATP gene, 79% identical to the rat MATP gene, 35% to the zebrafish version, and 30% identical to the fruitfly MATP gene.[32] The gene is best known in humans as being the location of a mutation that results in human type IV oculocutaneous albinism (OCA4). Type IV oculocutaneous albinism, like other types of human albinism, results in hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, with increased rates of skin cancer and reduced visual acuity.[33] None of these effects are associated with the equine cream gene. Other human MATP polymorphisms result in normal pigment variations, specifically fair skin, light eyes, and light hair in Caucasian populations.[9]

A polymorphism on the mouse MATP gene is known to be the cause of the underwhite coat color phenotype. The phenotype was first identified in the 1960s, and since then has been mapped successfully. Affected individuals have a reduction in eye and coat pigmentation, and irregularly shaped melanosomes.[24]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mariat, Denis; Sead Taourit; Gérard Guérin (2003). "A mutation in the MATP gene causes the cream coat colour in the horse". Genet. Sel. Evol. 35 (1). INRA, EDP Sciences: 119–133. doi:10.1051/gse:2002039. PMC 2732686. PMID 12605854.

- ^ a b c d e f "Introduction to Coat Color Genetics". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, University of California Davis. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Locke, MM; LS Ruth; LV Millon; MCT Penedo; JC Murray; AT Bowling (2001). "The cream dilution gene, responsible for the palomino and buckskin coat colors, maps to horse chromosome 21". Animal Genetics. 32 (6): 340–343. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2052.2001.00806.x. PMID 11736803.

The eyes and skin of palominos and buckskins are often slightly lighter than their non-dilute equivalents.

- ^ Cook, D; Brooks S; Bellone R; Bailey E (2008). Barsh, Gregory S. (ed.). "Missense Mutation in Exon 2 of SLC36A1 Responsible for Champagne Dilution in Horses". PLoS Genetics. 4 (9): e1000195. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000195. PMC 2535566. PMID 18802473.

Foals with one copy of CR also have pink skin at birth but their skin is slightly darker and becomes black/near black with age.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Laura Behning. "Palomino". Morgan Colors.

- ^ Laura Behning. "Buckskin". Morgan Colors.

- ^ Bowling A.T. (1996) Horse Genetics. pp. 25±8. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

- ^ Thiruvenkadan, AK; N Kandasamy; S Panneerselvam (2008). "Review: Coat colour inheritance in horses". Livestock Science. 117 (2–3). Elsevier: 109–129. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2008.05.008.

- ^ a b Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Solute Carrier Family 45, Member 2; SLC45A2 - 606202

- ^ Haase, B; Brooks, SA; Schlumbaum, A; Azor, PJ; Bailey, E; et al. (2007). "Allelic Heterogeneity at the Equine KIT Locus in Dominant White (W) Horses". PLoS Genet. 3 (11): e195. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195. PMC 2065884. PMID 17997609.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Breed Characteristics". American Quarter Horse Association. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ American Morgan Horse Association. "Guidelines to Coat Color and Coat Characteristics" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ^ "Coat Colors of TWHs". Colors and Markings. Tennessee Walking Horse Breeders' and Exhibitors' Association. Archived from the original on 2007-08-05. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ MFTHBA Color Panel. "What Color Is Your Horse?". Missouri Fox Trotting Horse Breed Association. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ American Miniature Horse Association. "Coat Color Chart". Registration. Archived from the original on 2009-11-09. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Akhal-Teke Association of America. "Colors of the Akhal-Teke". Breed Standards. Archived from the original on 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Adalsteinsson, S. (1974). "Inheritance of the palomino color in Icelandic horses". Journal of Heredity. 65 (1): 15–20. PMID 4847742.

- ^ Welsh Pony and Cob Society of America. "Description of the Welsh Mountain Pony" (PDF). 2008 Rule Book. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ The Jockey Club. "Coat Colors Of Thoroughbreds". Interactive RegistrationTM Help Desk: How to Identify a Thoroughbred. The Jockey Club. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ a b "Rules and regulations of registration". International Andalusian and Lusitano Horse Association. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ^ ANCCE. "Conformation Characteristics: P.R.E. breed prototype". Asociación Nacional de Criadores de Caballos de Pura Raza Española. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Arabian Horse Association. "How Do I... Determine Color & Markings?". Purebred Registration. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ " Introduction to Coat Color Genetics" from Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis. Web Site accessed March 27, 2008

- ^ a b Sweet, H.O.; Brilliant M.H.; Cook S.A.; Johnson K.R.; Davisson M.T. (1998). "A new allelic series for the underwhite gene on mouse chromosome 15". Journal of Heredity. 89 (6): 546–51. doi:10.1093/jhered/89.6.546. PMID 9864865.

- ^ Cremello & Perlino Educational Association. "Update". Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ^ Cremello & Perlino Educational Association. "The Facts and the Myths". Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Albinism Association of Australia. "What is Albinism?". Archived from the original on 2009-09-24. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rieder, S; Hagger C; Obexer-Ruff G; Leeb T; Poncet PA. (2008). "Genetic analysis of white facial and leg markings in the Swiss Franches-Montagnes Horse Breed". Journal of Heredity. 99 (2): 130–6. doi:10.1093/jhered/esm115. PMID 18296388.

- ^ Woolf, CM (Jul–Aug 1990). "Multifactorial inheritance of common white markings in the Arabian horse". Journal of Heredity. 81 (4): 240–6. PMID 2273238.

- ^ Woolf, CM (Mar–Apr 1991). "Common white facial markings in bay and chestnut Arabian horses and their hybrids". Journal of Heredity. 82 (2): 167–9. PMID 2013690.

- ^ Sheila Archer (2008-08-31). "Studies Currently Underway". The Appaloosa Project.

- ^ Wei Li (2008-08-30). "Oculocutaneous Albinism 4". Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome Database.

- ^ Newton, JM; Cohen-Barak O; Hagiwara N; Gardner JM; Davisson MT; King RA; Brilliant MH (November 2001). "Mutations in the Human Orthologue of the Mouse underwhite Gene (uw) Underlie a New Form of Oculocutaneous Albinism, OCA4". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (5): 981–8. doi:10.1086/324340. PMC 1274374. PMID 11574907.