Assassination of Alexander II of Russia: Difference between revisions

Jop2~enwiki (talk | contribs) m →The assassination: -doble phrase |

Telementor (talk | contribs) Major expansion of the article |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox event |

|||

[[File:Attentat mortal Alexander II (1881).jpg|thumb|''The assassination of Alexander II'' (1881), a drawing by {{Interlanguage link multi|Gustaf Broling|sv}}]] |

|||

|title= Assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia |

|||

The '''assassination of Tsar [[Alexander II of Russia]]''' took place on March 13, 1881 ([[Old Style]]: March 1, 1881), in [[Saint Petersburg]], [[Russian Empire|Russia]]. Alexander was killed while traveling to [[Mikhailovsky Manège]] in a closed carriage after one assassin threw a bomb which damaged the carriage, prompting Alexander to dismount, at which point a second assassin threw a bomb that landed at the Tsar's feet. |

|||

|image=Konstantin Makovsky Alexander II na smertnom odre 1881.jpg |

|||

|image_size= |

|||

|caption=Painting of Alexander II on his deathbed by [[Konstantin Makovsky]] |

|||

|Location=Near the [[Catherine Canal]], [[Saint Petersburg]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|59|56|24|N|30|19|43|E|type:landmark_region:RU|display=inline,title}} |

|||

|Deaths=[[Alexander II of Russia]], [[Ignacy Hryniewiecki]], Alexander Maleichev, Nikolai M. Zakharov, and possibly others. |

|||

|Date={{start date and age|1881|03|13}} |

|||

| accused = |

|||

| convicted = [[Assassination of Alexander II of Russia#Arrests, trials, and punishments|Members of Narodnaya Volya]] |

|||

| charges = [[Regicide]] |

|||

| blank_label = Weapon |

|||

|blank_data=Nitroglycerin and pyroxilin bombs |

|||

| trial = |

|||

| verdict = |

|||

| convictions = |

|||

| sentence = |

|||

| notes = |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''assassination of [[Tsar]] [[Alexander II of Russia]]''' took place on 13 March [1 March, [[Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates|Old Style]]], 1881 in [[Saint Petersburg]], [[Russian Empire|Russia]]. Alexander II was killed while returning to the [[Winter Palace]] from [[Mikhailovsky Manège]] in a closed carriage. |

|||

Alexander II had previously survived several attempts on his life.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.rbth.com/arts/2016/09/07/6-facts-about-alexander-ii-the-tsar-liberator-killed-by-revolutionaries_627977|title=6 facts about Alexander II: The tsar-liberator killed by revolutionaries|date=September 7, 2016|newspaper=Russia Beyond}}</ref> The assassination is popularly considered to be one of the most successful actions by the Russian Nihilist movement of the 19th century. |

|||

The assassination was planned by the Executive Committee of [[Narodnaya Volya]] ("People's Will"), chiefly by [[Andrei Zhelyabov]]. Of the four assassins coordinated by [[Sophia Perovskaya]], two of them actually committed the deed. One assassin, [[Nikolai Rysakov]], threw a bomb which damaged the carriage, prompting the Tsar to dismount. At this point a second assassin, [[Ignacy Hryniewiecki]], threw a bomb that fatally wounded Alexander II. |

|||

Alexander II had previously survived several attempts on his life, including the attempts by [[Dmitry Karakozov]] and [[Alexander Soloviev (revolutionary)|Alexander Soloviev]], the attempt to dynamite the imperial train in [[Zaporizhia]], and the bombing of the [[Winter Palace]] in February 1880. The assassination is popularly considered to be the most successful action by the Russian Nihilist movement of the 19th century. |

|||

==The conspirators== |

==The conspirators== |

||

{{main|Pervomartovtsy|Narodnaya Volya}} |

{{main|Pervomartovtsy|Narodnaya Volya}} |

||

On 25–26 August of 1879, on the anniversary of his coronation, the 22-member Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya, resolved to assassinate Alexander II in the hopes that it would precipitate a revolution.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=273}}{{sfn|Kirschenbaum|2014|p=12}} Over the subsequent year and a half, the various attempts on Alexander's life had ended in failure. The Committee then decided to assassinate Alexander II on his way back to the Winter Palace following his usual Sunday visit to the Mikhailovsky Manège. Andrei Zhelyabov was the chief organizer of the plot. The group had observed his routines for a couple of months and was able to deduce the alternate intentions of the entourage. They found that the Tsar would either head for home by going through [[Malaya Sadovaya Street]] or by driving along the [[Catherine Canal]]. If by the Malaya Sadovaya, the plan was to detonate a mine placed under the street. To further insure the success of the plot, four bomb-throwers were to loiter at the corners of the street; after the explosion, all of them were to close in on the Tsar and use their bombs if necessary. If, on the other hand, Tsar passed by the Canal, the bomb-throwers alone were to be relied upon. Ignacy Hryniewiecki (Ignaty Grinevitsky), Nikolai Rysakov, [[Timofey Mikhailov]], and [[Ivan Yemelyanov]] had volunteered as bomb-throwers.{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}}{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=273}} |

|||

The assassination was planned by the Executive Committee of [[Narodnaya Volya]] ("The People's Will"), a terrorist revolutionary organization formed in 1879. [[Andrei Zhelyabov]] was the chief organizer. When Zhelyabov was arrested a few days prior to the attack, his wife [[Sophia Perovskaya]] took the reins. |

|||

The group opened a cheese store in Malaya Sadovaya, and used one of the rooms to dig a tunnel extending to the middle of the street, where they would lay large quantities of dynamite. The hand-held bombs were designed and chiefly manufactured by [[Nikolai Kibalchich]]. The night before the attack, Perovskaya along with [[Vera Figner]] (also one of seven women on the Executive Committee) helped assemble the bombs.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=273}}{{sfn|Kirschenbaum|2014|p=12}} |

|||

Zhelyabov was to have directed the bombing, and he was supposed to assail Alexander II with dagger or pistol in case both the mine and the bombs were unsuccessful. When Zhelyabov was arrested two days prior to the attack, his wife Sophia Perovskaya took the reins.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=276}} |

|||

<gallery mode="packed"> |

<gallery mode="packed"> |

||

| Line 16: | Line 42: | ||

File:Emelyanov Ivan Panteleymonovich.jpg | [[Ivan Yemelyanov]] |

File:Emelyanov Ivan Panteleymonovich.jpg | [[Ivan Yemelyanov]] |

||

File:Kibalchich.jpg| [[Nikolai Kibalchich]] |

File:Kibalchich.jpg| [[Nikolai Kibalchich]] |

||

File:Mikhailov tm.jpg| [[Timofey |

File:Mikhailov tm.jpg| [[Timofey Mikhailov]] |

||

File:G Gelfman.jpg| [[Hesya Helfman]] |

File:G Gelfman.jpg| [[Hesya Helfman]] |

||

File:N A Sablin.jpg| [[Nikolai Sablin]] |

File:N A Sablin.jpg| [[Nikolai Sablin]] |

||

File:Vera Figner.jpg| [[Vera Figner]] |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

==The assassination== |

==The assassination== |

||

The Tsar travelled both to and from the ''Manège'' in a closed two-seater carriage drawn by a pair of horses. He was accompanied by five mounted [[Cossacks]] and Frank (Franciszek) Joseph Jackowski, a Polish noble, with a sixth Cossack sitting on the coachman's left. The emperor's carriage was followed by three sleighs carrying, among others, the chief of police Colonel Dvorzhitzky and two officers of the [[Gendarmerie]].{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}} |

|||

[[File:Alexander II of Russia's murder 02.jpg|thumb|The explosion killed one of the Cossacks and wounded the driver.]] |

|||

On the afternoon of 13 March, after having watched the manoeuvres of two Guard battalions at the ''Manège'', the Tsar's carriage turned into Bolshaya Italyanskaya Street, thus avoiding the mine in Malaya Sadovaya. Perovskaya, by taking out a handkerchief and blowing her nose as a predetermined signal, dispatched the assassins to the Canal. On his way back, the Tsar also decided to pay a brief visit to his cousin, the Grand Duchess Catherine. This gave the bombers ample time to reach the Canal on foot; with the exception of Mikhailov, they all took up their new positions.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=278}} |

|||

As he was known to do every Sunday for many years, the emperor went to the [[Mikhailovsky Manège]] for the military [[wikt:roll call|roll call]]. He travelled both to and from the ''Manège'' in a closed carriage accompanied by five [[Cossacks]] and Frank (Franciszek) Joseph Jackowski, a Polish noble, with a sixth Cossack<ref name="Richard J Harris, Newport Beach, CA USA">{{cite book|last=Harris|first=Richard|title=Mother's recounting of her father's experience}}</ref> sitting on the coachman's left. The emperor's carriage was followed by two sleighs carrying, among others, the chief of police and the chief of the emperor's guards. The route, as always, was via the [[Catherine Canal]] and over the [[Pevchesky Bridge]]. |

|||

[[File:Alexander II of Russia's murder 02.jpg|thumb|The scene of the assassination immediately after the explosion of the first bomb.]] |

|||

The street was flanked by narrow pavements for the public. [[Nikolai Rysakov|Rysakov]] was there, carrying a small white package wrapped in a handkerchief.<ref name="Rowley"/> He later said of his attempt to kill the Tsar: |

|||

At 2:15 PM, the carriage had gone about 150 yards down the quay until it encountered Rysakov who was carrying a bomb wrapped in a handkerchief. On the signal being given by Perovskaya, Rysakov threw the bomb under the Tsar's carriage. The Cossack who rode behind (Alexander Maleichev) was mortally wounded and died shortly that day. Among those injured was a fourteen year old peasant boy (Nikolai Zakharov) who served as a delivery boy in a butcher's shop. However, the explosion had only damaged the [[Bulletproofing|bulletproof]] carriage. The emperor emerged shaken but unhurt. Rysakov was captured almost immediately. Police Chief Dvorzhitsky heard Rysakov shout out to someone else in the gathering crowd. The coachman implored the Emperor not to alight. Dvorzhitzky offered to drive the Tsar back to the Palace in his sleigh. The Tsar agreed, but he decided to first see the culprit, and to survey the damage. He expressed solicitude for the victims. To the anxious inquires of his entourage, Alexander replied, "Thank God, I'm untouched".{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}}{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=280}}{{sfn|Hartnett|2001|p=251}} |

|||

[[Image:The uniform of Alexander II.jpg|thumb|right|The uniform worn by Alexander II during the assassination.]] |

|||

{{quote|After a moment's hesitation I threw the bomb. I sent it under the horses' hooves in the supposition that it would blow up under the carriage... The explosion knocked me into the fence.<ref name="Radzinsky-p413"/>}} |

|||

He was ready to drive away when a second bomber, Hryniewiecki, who had come close to the Tsar, made a sudden movement, throwing a bomb at his feet. A second explosion ripped through the air and the Emperor and his assassin fell to the ground terribly injured. Since people had crowded close to the Tsar, Hryniewiecki's bomb claimed more injuries than the first (according to Dvorzhitsky, who was himself injured, there were about 20 people with wounds of varying degree). Alexander was leaning on his right arm. His legs were shattered below the knee from which he was bleeding profusely, his abdomen was torn open, and his face was mutilated. Hryniewiecki himself, also gravely wounded from the blast, lay next to the Tsar and the butcher's boy.{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}}{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=279}} |

|||

Ivan Yemelyanov, the third bomber in the crowd, stood ready, clutching a briefcase containing a bomb that would be used if the other two bombers failed. However, he instead along with other bystanders rushed to answer the Tsar's barely audible cries for help; he could barely whisper: "Take me to the palace... there... I will die."{{sfn|Hartnett|2001|p=251}}{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=281}} Alexander was carried by sleigh to his study in the Winter Palace, where almost the same day twenty years earlier, he had signed the [[Emancipation reform of 1861|Emancipation Edict]] freeing the serfs. Members of the [[Romanov family]] came rushing to the scene. The dying emperor was given [[Eucharist|Communion]] and [[Last rites#In the Orthodox Church|Last Rites]]. When the attending physician, [[Sergey Botkin]], was asked how long it would be, he replied, "Up to fifteen minutes." At 3:30 that day, the personal flag of Alexander II was lowered for the last time.{{sfn|Radzinsky|2005|p=419}} |

|||

The explosion, while killing one of the Cossacks and seriously wounding the driver and people on the sidewalk,<ref name="Rowley"/> had only damaged the [[Bulletproofing|bulletproof]] carriage. The emperor emerged shaken but unhurt.<ref name="Rowley"/> Rysakov was captured almost immediately. Police Chief Dvorzhitsky heard Rysakov shout out to someone else in the gathering crowd. The surrounding guards and the Cossacks urged the emperor to leave the area at once rather than being shown the site of the explosion. |

|||

==Arrests, trials, and punishments== |

|||

To the anxious inquires of his entourage, Alexander replied, "Thank God, I'm untouched."<ref name="Massie-p16"/> |

|||

The thrower of the fatal second bomb, Hryniewiecki, was carried to the military hospital nearby, where he lingered in agony for several hours. Refusing to cooperate with the authorities or even to give his name, he died that evening.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=280}} In an attempt to save his own life, Rysakov, the first bomb-thrower who had been captured at the scene, cooperated with the investigators. His testimony implicated the other participants, and enabled the police to raid the group's headquarters. The raid took place on March 15, two days after the assassination. Helfman was arrested and Sablin fired several shots at the police and then shot himself to avoid capture. Mikhailov was captured in the same building the next day after a brief gunfight. The tsarist police apprehended Sophia Perovskaya on March 22, Nikolai Kibalchich on March 29, and Ivan Yemelyanov on April 14.{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}}{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=283}} |

|||

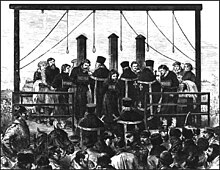

[[Image:Execution Nikolai Kibalchich.jpg|thumb|right|The execution of the conspirators on the parade grounds of the [[Semyonovsky Regiment]]. On the left, the executioner Frolov, described as a strongly-built man of the peasant class.{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}}{{sfn|EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS}} Convicts from left to right: Rysakov, Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, and Mikhailov.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=307}}]] |

|||

Nevertheless, a second young member of the ''Narodnaya Volya'', [[Ignacy Hryniewiecki]],<ref name="Rowley"/> standing by the canal fence, raised both arms and threw something at the emperor's feet. He was alleged to have shouted, "It is too early to thank God!"<ref name="Massie-p16"/> Dvorzhitsky was later to write: |

|||

Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Helfman, Mikhailov, and Rysakov were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was duly carried out upon the State criminals on April 15, 1881. In the case of Hesya Helfman, her execution was deferred on account of her pregnancy.{{sfn|EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS}}{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=288}} [[Alexander III of Russia|Alexander III]] later commuted her sentence of death to [[katorga]] (forced labor) for an indefinite period of time. She died of a post-natal complication in January 1882, and her infant daughter did not long survive her.{{sfn|Yarmolinsky|2016|p=287}} |

|||

Yemelyanov was tried the following year and was sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor, however, he received a pardon from the Tsar after serving 20 years.{{sfn|Kel'ner|2015}} Vera Figner remained at large until 10 February 1883, during this time she orchestrated the assassination of General Mayor Strelnikov, the military prosecutor of [[Odessa]]. In 1884, Figner was sentenced to die by hanging which was then commuted to indefinite penal servitude. She likewise served for 20 years until a plea from her dying mother persuaded the last tsar, [[Nicholas II]], to set her free.{{sfn|Kirschenbaum|2014|p=12}}{{sfn|Hartnett|2001|p=255}} |

|||

{{quote|I was deafened by the new explosion, burned, wounded and thrown to the ground. Suddenly, amid the smoke and snowy fog, I heard His Majesty's weak voice cry, 'Help!' Gathering what strength I had, I jumped up and rushed to the emperor. His Majesty was half-lying, half-sitting, leaning on his right arm. Thinking he was merely wounded heavily, I tried to lift him but the czar's legs were shattered, and the blood poured out of them. Twenty people, with wounds of varying degree, lay on the sidewalk and on the street. Some managed to stand, others to crawl, still others tried to get out from beneath bodies that had fallen on them. Through the snow, debris, and blood you could see fragments of clothing, epaulets, sabres, and bloody chunks of human flesh.<ref name="Radzinsky-p415"/>}} |

|||

Nearby, Hryniewiecki himself lay unconscious from the blast.<ref name="Yarmolinsky"/> |

|||

Later, it was learned there was a third bomber in the crowd. [[Ivan Yemelyanov]] stood ready, clutching a briefcase containing a bomb that would be used if the other two bombers failed. |

|||

Alexander was carried by sleigh to the [[Winter Palace]]<ref name="Rowley" /> to his study where almost the same day twenty years earlier, he had signed the [[Emancipation reform of 1861|Emancipation Edict]] freeing the serfs. Alexander was bleeding to death, with his legs torn away, his stomach ripped open, and his face mutilated.<ref>Massie, p. 16</ref> Members of the [[Romanov family]] came rushing to the scene. |

|||

The dying emperor was given [[Eucharist|Communion]] and [[Last rites#In the Orthodox Church|Last Rites]]. When the attending physician, [[Sergey Botkin]], was asked how long it would be, he replied, "Up to fifteen minutes."<ref name="Radzinsky-p419"/> At 3:30 that day, the personal flag of Alexander II was lowered for the last time.<ref name="Yarmolinsky"/> |

|||

==Arrests, trials, and executions== |

|||

[[Image:Execution Nikolai Kibalchich.jpg|thumb|right|The execution of the conspirators on the parade grounds of the [[Semyonovsky Regiment]].]] |

|||

The first bomb-thrower, [[Nikolai Rysakov]], had been captured at the scene. |

|||

The thrower of the fatal second bomb, [[Ignacy Hryniewiecki]], had wounded himself fatally during the assassination. He was carried to the infirmary, where he regained consciousness around 9:00 that night, but refused to cooperate with the authorities or even to give his name. He died that night.<ref name="Yarmolinsky"/> |

|||

[[Sophia Perovskaya]] was arrested on March 22 ([[Old Style]]: March 10) [[Nikolai Kibalchich]] on March 29 ([[Old Style]]: March 17). On March 15 ([[Old Style]]: March 3), two days after the assassination, the police came for [[Hesya Helfman]] and [[Nikolai Sablin]]; Sablin shot himself rather than be captured. |

|||

Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Helfman, Mikhailov, and Rysakov were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging. |

|||

During the trial, in an attempt to save his own life, Rysakov cooperated with the investigators by giving them valuable information about his accomplices.<ref name="Crankshaw-p270">{{cite book |author=Edward Crankshaw |title=The Shadow of the Winter Palace |url=https://archive.org/details/shadowofwinterpa00cran |url-access=registration |publisher=Viking Press |location=New York |date=1976 |page=[https://archive.org/details/shadowofwinterpa00cran/page/270 270]}}</ref> |

|||

On April 15, 1881 ([[Old Style]]: April 3, 1881),<ref>{{cite web |title=1881: The assassins of Tsar Alexander II |website=Executed Today |url=http://www.executedtoday.com/2009/04/15/1881-the-assassins-of-tsar-alexander-ii/ |date=2009-04-15 |accessdate=2018-12-26 |quote=April 15 was the date on the Gregorian calendar; per the Julian calendar still in use in Russia at the time, the date was April 3.}}</ref> all but Helfman were hanged. Kibalchich was hanged first; Mikhailov was second. Rysakov, the cooperator, was hanged last. |

|||

Helfman's execution was postponed due to her pregnancy. Her sentence of death was later replaced with [[katorga]] (forced labor) for an indefinite period of time. She died of a post-natal complication in January 1882.{{citation needed|date=December 2018}} |

|||

==Aftermath== |

==Aftermath== |

||

[[File:Sankt petersburg auferstehungskirche.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Church of the Savior on Blood]] was erected on the site of the assassination.]] |

[[File:Sankt petersburg auferstehungskirche.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Church of the Savior on Blood]] was erected on the site of the assassination.]] |

||

[[File:Interiors of the Church of the Saviour on the Blood12.JPG|thumb|right|The cobblestones of the old road, the flagstones of the sidewalk, and the iron railing along the edge of the quay where the assassination took place.]] |

|||

A temporary shrine was erected on the site of the attack while plans and fundraising for a more permanent memorial were undertaken. In order to build a permanent shrine on the exact spot where the assassination took place, it was decided to narrow the canal so that the section of road on which the tsar had been driving could be included within the walls of the church. |

|||

A temporary shrine was erected on the site of the attack while plans and fundraising for a more permanent memorial were undertaken. In order to build a permanent shrine on the exact spot where the assassination took place, it was decided to narrow the canal so that the section of road on which the tsar had been driving could be included within the walls of the church. The permanent memorial took the form of the [[Church of the Savior on Blood]]. Construction began in 1883 under Alexander III, and was completed in 1907 under Nicholas II. An elaborate shrine, in the form of a [[Ciborium (architecture)|ciborium]], was constructed at the end of the church opposite the altar, on the exact place of Alexander's assassination. It is embellished with [[topaz]], [[lazurite]], and other semi-precious stones, making a striking contrast with the simple cobblestones of the old road, which are exposed in the floor of the shrine.{{sfn|SacredDestinations}} |

|||

The permanent memorial took the form of the [[Church of the Savior on Blood]]. Construction began in 1883 under [[Alexander III of Russia|Alexander III]], and was completed in 1907 under [[Nicholas II of Russia|Nicholas II]]. |

|||

An elaborate shrine, in the form of a [[Ciborium (architecture)|ciborium]], was constructed at the end of the church opposite the altar, on the exact place of Alexander's assassination. It is embellished with [[topaz]], [[lazurite]], and other semi-precious stones,<ref name="SacredDestinations"/> making a striking contrast with the simple cobblestones of the old road, which are exposed in the floor of the shrine. |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

===Citations=== |

|||

<references> |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

<ref name="Massie-p16">{{cite book |author=Robert K. Massie |title=Nicholas and Alexandra |publisher=Dell Publishing Company |location=New York |page=16}}</ref> |

|||

=== Bibliography === |

|||

<ref name="Radzinsky-p413">{{cite book |author=Edvard Radzinsky |title=Alexander II: The Last Great Czar |publisher=Freepress |date=2005 |page=413}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Yarmolinsky |first1=Avrahm |title=Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism |year=2016 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0691638546| ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Kel'ner |first1=Viktor Efimovich |title=1 marta 1881 goda: Kazn imperatora Aleksandra II (1 марта 1881 года: Казнь императора Александра II) |year=2015 |publisher=Lenizdat |isbn=5-289-01024-6| ref=harv}} |

|||

<ref name="Radzinsky-p415">{{cite book |author=Edvard Radzinsky |title=Alexander II: The Last Great Czar |publisher=Freepress |date=2005 |page=415}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Edvard|first1= Radzinsky |title=Alexander II: The Last Great Czar |publisher=Freepress |year=2005|isbn=978-0743284264| ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=Church of the Savior on Blood, St. Petersburg | url=http://www.sacred-destinations.com/russia/st-petersburg-church-of-savior-on-blood |accessdate = 2018-12-20 |website=Sacred Destinations| ref=CITEREFSacredDestinations}} |

|||

<ref name="Rowley">{{cite journal |author=Alison Rowley |title=Dark Tourism and the Death of Russian Emperor Alexander II, 1881–1891 |journal=Historian |date=Summer 2017 |volume=79 |issue=2 |pages=229–55 |doi=10.1111/hisn.12503}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite journal|last1=Hartnett|first1=L.|title= The Making of a Revolutionary Icon: Vera Nikolaevna Figner and the People's Will in the Wake of the Assassination of Tsar Aleksandr II|journal=Canadian Slavonic Papers|year=2001|volume=43|issue=2/3|pages=249-270|jstor=40870322| ref=harv}} |

|||

<ref name="SacredDestinations">{{cite web |url=http://www.sacred-destinations.com/russia/st-petersburg-church-of-savior-on-blood |title=Church of the Savior on Blood, St. Petersburg |accessdate = 2018-12-20 |website=Sacred Destinations}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite journal|last1=Kirschenbaum|first1=Lisa A.|title= The Noble Terrorist|journal=The Women's Review of Books|year=2014|volume=31|pages=12–13|jstor=24430570| ref=harv}} |

|||

<ref name="Yarmolinsky">{{cite book |author=Avrahm Yarmolinsky |title=Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism |url=http://www.ditext.com/yarmolinsky/yar14.html}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite news |title=EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS |url=https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/70956378 |accessdate=2 December 2019 |publisher=Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907) |date=4 June 1881| ref=CITEREFEXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS}} |

|||

</references> |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander 02 Of Russia}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander 02 Of Russia}} |

||

Revision as of 12:20, 13 December 2019

Painting of Alexander II on his deathbed by Konstantin Makovsky | |

| Date | March 13, 1881 |

|---|---|

| Location | Near the Catherine Canal, Saint Petersburg |

| Coordinates | 59°56′24″N 30°19′43″E / 59.94000°N 30.32861°E |

| Deaths | Alexander II of Russia, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, Alexander Maleichev, Nikolai M. Zakharov, and possibly others. |

| Convicted | Members of Narodnaya Volya |

| Charges | Regicide |

| Weapon | Nitroglycerin and pyroxilin bombs |

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia took place on 13 March [1 March, Old Style], 1881 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Alexander II was killed while returning to the Winter Palace from Mikhailovsky Manège in a closed carriage.

The assassination was planned by the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya ("People's Will"), chiefly by Andrei Zhelyabov. Of the four assassins coordinated by Sophia Perovskaya, two of them actually committed the deed. One assassin, Nikolai Rysakov, threw a bomb which damaged the carriage, prompting the Tsar to dismount. At this point a second assassin, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, threw a bomb that fatally wounded Alexander II.

Alexander II had previously survived several attempts on his life, including the attempts by Dmitry Karakozov and Alexander Soloviev, the attempt to dynamite the imperial train in Zaporizhia, and the bombing of the Winter Palace in February 1880. The assassination is popularly considered to be the most successful action by the Russian Nihilist movement of the 19th century.

The conspirators

On 25–26 August of 1879, on the anniversary of his coronation, the 22-member Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya, resolved to assassinate Alexander II in the hopes that it would precipitate a revolution.[1][2] Over the subsequent year and a half, the various attempts on Alexander's life had ended in failure. The Committee then decided to assassinate Alexander II on his way back to the Winter Palace following his usual Sunday visit to the Mikhailovsky Manège. Andrei Zhelyabov was the chief organizer of the plot. The group had observed his routines for a couple of months and was able to deduce the alternate intentions of the entourage. They found that the Tsar would either head for home by going through Malaya Sadovaya Street or by driving along the Catherine Canal. If by the Malaya Sadovaya, the plan was to detonate a mine placed under the street. To further insure the success of the plot, four bomb-throwers were to loiter at the corners of the street; after the explosion, all of them were to close in on the Tsar and use their bombs if necessary. If, on the other hand, Tsar passed by the Canal, the bomb-throwers alone were to be relied upon. Ignacy Hryniewiecki (Ignaty Grinevitsky), Nikolai Rysakov, Timofey Mikhailov, and Ivan Yemelyanov had volunteered as bomb-throwers.[3][1]

The group opened a cheese store in Malaya Sadovaya, and used one of the rooms to dig a tunnel extending to the middle of the street, where they would lay large quantities of dynamite. The hand-held bombs were designed and chiefly manufactured by Nikolai Kibalchich. The night before the attack, Perovskaya along with Vera Figner (also one of seven women on the Executive Committee) helped assemble the bombs.[1][2]

Zhelyabov was to have directed the bombing, and he was supposed to assail Alexander II with dagger or pistol in case both the mine and the bombs were unsuccessful. When Zhelyabov was arrested two days prior to the attack, his wife Sophia Perovskaya took the reins.[4]

The assassination

The Tsar travelled both to and from the Manège in a closed two-seater carriage drawn by a pair of horses. He was accompanied by five mounted Cossacks and Frank (Franciszek) Joseph Jackowski, a Polish noble, with a sixth Cossack sitting on the coachman's left. The emperor's carriage was followed by three sleighs carrying, among others, the chief of police Colonel Dvorzhitzky and two officers of the Gendarmerie.[3]

On the afternoon of 13 March, after having watched the manoeuvres of two Guard battalions at the Manège, the Tsar's carriage turned into Bolshaya Italyanskaya Street, thus avoiding the mine in Malaya Sadovaya. Perovskaya, by taking out a handkerchief and blowing her nose as a predetermined signal, dispatched the assassins to the Canal. On his way back, the Tsar also decided to pay a brief visit to his cousin, the Grand Duchess Catherine. This gave the bombers ample time to reach the Canal on foot; with the exception of Mikhailov, they all took up their new positions.[5]

At 2:15 PM, the carriage had gone about 150 yards down the quay until it encountered Rysakov who was carrying a bomb wrapped in a handkerchief. On the signal being given by Perovskaya, Rysakov threw the bomb under the Tsar's carriage. The Cossack who rode behind (Alexander Maleichev) was mortally wounded and died shortly that day. Among those injured was a fourteen year old peasant boy (Nikolai Zakharov) who served as a delivery boy in a butcher's shop. However, the explosion had only damaged the bulletproof carriage. The emperor emerged shaken but unhurt. Rysakov was captured almost immediately. Police Chief Dvorzhitsky heard Rysakov shout out to someone else in the gathering crowd. The coachman implored the Emperor not to alight. Dvorzhitzky offered to drive the Tsar back to the Palace in his sleigh. The Tsar agreed, but he decided to first see the culprit, and to survey the damage. He expressed solicitude for the victims. To the anxious inquires of his entourage, Alexander replied, "Thank God, I'm untouched".[3][6][7]

He was ready to drive away when a second bomber, Hryniewiecki, who had come close to the Tsar, made a sudden movement, throwing a bomb at his feet. A second explosion ripped through the air and the Emperor and his assassin fell to the ground terribly injured. Since people had crowded close to the Tsar, Hryniewiecki's bomb claimed more injuries than the first (according to Dvorzhitsky, who was himself injured, there were about 20 people with wounds of varying degree). Alexander was leaning on his right arm. His legs were shattered below the knee from which he was bleeding profusely, his abdomen was torn open, and his face was mutilated. Hryniewiecki himself, also gravely wounded from the blast, lay next to the Tsar and the butcher's boy.[3][8]

Ivan Yemelyanov, the third bomber in the crowd, stood ready, clutching a briefcase containing a bomb that would be used if the other two bombers failed. However, he instead along with other bystanders rushed to answer the Tsar's barely audible cries for help; he could barely whisper: "Take me to the palace... there... I will die."[7][9] Alexander was carried by sleigh to his study in the Winter Palace, where almost the same day twenty years earlier, he had signed the Emancipation Edict freeing the serfs. Members of the Romanov family came rushing to the scene. The dying emperor was given Communion and Last Rites. When the attending physician, Sergey Botkin, was asked how long it would be, he replied, "Up to fifteen minutes." At 3:30 that day, the personal flag of Alexander II was lowered for the last time.[10]

Arrests, trials, and punishments

The thrower of the fatal second bomb, Hryniewiecki, was carried to the military hospital nearby, where he lingered in agony for several hours. Refusing to cooperate with the authorities or even to give his name, he died that evening.[6] In an attempt to save his own life, Rysakov, the first bomb-thrower who had been captured at the scene, cooperated with the investigators. His testimony implicated the other participants, and enabled the police to raid the group's headquarters. The raid took place on March 15, two days after the assassination. Helfman was arrested and Sablin fired several shots at the police and then shot himself to avoid capture. Mikhailov was captured in the same building the next day after a brief gunfight. The tsarist police apprehended Sophia Perovskaya on March 22, Nikolai Kibalchich on March 29, and Ivan Yemelyanov on April 14.[3][11]

Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Helfman, Mikhailov, and Rysakov were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was duly carried out upon the State criminals on April 15, 1881. In the case of Hesya Helfman, her execution was deferred on account of her pregnancy.[12][14] Alexander III later commuted her sentence of death to katorga (forced labor) for an indefinite period of time. She died of a post-natal complication in January 1882, and her infant daughter did not long survive her.[15]

Yemelyanov was tried the following year and was sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor, however, he received a pardon from the Tsar after serving 20 years.[3] Vera Figner remained at large until 10 February 1883, during this time she orchestrated the assassination of General Mayor Strelnikov, the military prosecutor of Odessa. In 1884, Figner was sentenced to die by hanging which was then commuted to indefinite penal servitude. She likewise served for 20 years until a plea from her dying mother persuaded the last tsar, Nicholas II, to set her free.[2][16]

Aftermath

A temporary shrine was erected on the site of the attack while plans and fundraising for a more permanent memorial were undertaken. In order to build a permanent shrine on the exact spot where the assassination took place, it was decided to narrow the canal so that the section of road on which the tsar had been driving could be included within the walls of the church. The permanent memorial took the form of the Church of the Savior on Blood. Construction began in 1883 under Alexander III, and was completed in 1907 under Nicholas II. An elaborate shrine, in the form of a ciborium, was constructed at the end of the church opposite the altar, on the exact place of Alexander's assassination. It is embellished with topaz, lazurite, and other semi-precious stones, making a striking contrast with the simple cobblestones of the old road, which are exposed in the floor of the shrine.[17]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 273.

- ^ a b c Kirschenbaum 2014, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kel'ner 2015.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 276.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 278.

- ^ a b Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 280.

- ^ a b Hartnett 2001, p. 251.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 279.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 281.

- ^ Radzinsky 2005, p. 419.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 283.

- ^ a b EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 307.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 288.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 287.

- ^ Hartnett 2001, p. 255.

- ^ SacredDestinations.

Bibliography

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2016). Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691638546.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Kel'ner, Viktor Efimovich (2015). 1 marta 1881 goda: Kazn imperatora Aleksandra II (1 марта 1881 года: Казнь императора Александра II). Lenizdat. ISBN 5-289-01024-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Edvard, Radzinsky (2005). Alexander II: The Last Great Czar. Freepress. ISBN 978-0743284264.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- "Church of the Savior on Blood, St. Petersburg". Sacred Destinations. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- Hartnett, L. (2001). "The Making of a Revolutionary Icon: Vera Nikolaevna Figner and the People's Will in the Wake of the Assassination of Tsar Aleksandr II". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 43 (2/3): 249–270. JSTOR 40870322.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa A. (2014). "The Noble Terrorist". The Women's Review of Books. 31: 12–13. JSTOR 24430570.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- "EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS". Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907). 4 June 1881. Retrieved 2 December 2019.