Cartesian coordinate system: Difference between revisions

m clean up using AWB |

m spelling |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

== In physics == |

== In physics == |

||

The above discussion applies to Cartesian coordinate systems in mathematics, where it is common to not use any units of measurement. In physics it is important to note that a dimension is simply a measure of something, and that, for each class of features to be measured, another dimension can be added. Attachment to |

The above discussion applies to Cartesian coordinate systems in mathematics, where it is common to not use any units of measurement. In physics it is important to note that a dimension is simply a measure of something, and that, for each class of features to be measured, another dimension can be added. Attachment to visualising the dimensions precludes understanding the many different dimensions that can be measured (time, mass, color, cost, etc.). Multi-dimensional objects can be calculated and manipulated algebraically. |

||

== Further notes == |

== Further notes == |

||

In [[analytic geometry]] the Cartesian coordinate system is the foundation for the algebraic manipulation of geometrical shapes. Many other coordinate systems have been developed since Descartes. One common set of systems use [[coordinates (elementary mathematics)|polar coordinates]]; astronomers often use [[spherical coordinates]], a type of polar coordinate system. In different branches of mathematics coordinate systems can be transformed, translated, rotated, and re-defined altogether to simplify calculation and for |

In [[analytic geometry]] the Cartesian coordinate system is the foundation for the algebraic manipulation of geometrical shapes. Many other coordinate systems have been developed since Descartes. One common set of systems use [[coordinates (elementary mathematics)|polar coordinates]]; astronomers often use [[spherical coordinates]], a type of polar coordinate system. In different branches of mathematics coordinate systems can be transformed, translated, rotated, and re-defined altogether to simplify calculation and for specialised ends. |

||

It may be interesting to note that some have indicated that the master artists of the [[Renaissance]] used a grid, in the form of a wire mesh, as a tool for breaking up the component parts of their subjects they painted. That this may have influenced Descartes is merely speculative. (See [[Perspective (graphical)|perspective]], [[projective geometry]].) |

It may be interesting to note that some have indicated that the master artists of the [[Renaissance]] used a grid, in the form of a wire mesh, as a tool for breaking up the component parts of their subjects they painted. That this may have influenced Descartes is merely speculative. (See [[Perspective (graphical)|perspective]], [[projective geometry]].) |

||

Revision as of 17:17, 23 December 2006

In mathematics, the Cartesian coordinate system is used to uniquely determine each point in the plane through two numbers, usually called the x-coordinate and the y-coordinate of the point. To define the coordinates, two perpendicular directed lines (the x-axis or abscissa and the y-axis or ordinate), are specified, as well as the unit length, which is marked off on the two axes (see Figure 1). Cartesian coordinate systems are also used in space (where three coordinates are used) and in higher dimensions.

Using the Cartesian coordinate system geometric shapes (such as curves) can be described by algebraic equations, namely equations satisfied by the coordinates of the points lying on the shape. For example, the circle of radius 2 may be described by the equation x² + y² = 4 (see Figure 2).

Cartesian means relating to the French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes, who, among other things, worked to merge algebra and Euclidean geometry. This work was influential in the development of analytic geometry, calculus, and cartography.

The idea of this system was developed in 1637 in two writings by Descartes. In part two of his Discourse on Method he introduces the new idea of specifying the position of a point or object on a surface, using two intersecting axes as measuring guides. In La Géométrie, he further explores the above-mentioned concepts.

See coordinates (mathematics) for other commonly used coordinate systems such as polar coordinates and coordinate systems for usage of the term in advanced mathematics.

Two-dimensional coordinate system

The modern Cartesian coordinate system in two dimensions (also called a rectangular coordinate system) is commonly defined by two axes, at right angles to each other, forming a plane (an xy-plane). The horizontal axis is normally labeled x, and the vertical axis is normally labeled y. In a three dimensional coordinate system, another axis, normally labeled z, is added, providing a third dimension of space measurement. The axes are commonly defined as mutually orthogonal to each other (each at a right angle to the other). (Early systems allowed "oblique" axes, that is, axes that did not meet at right angles, and such systems are occasionally used today, although mostly as theoretical exercises.) All the points in a Cartesian coordinate system taken together form a so-called Cartesian plane. Equations that use the Cartesian coordinate system are called Cartesian equations.

The point of intersection, where the axes meet, is called the origin normally labeled O. The x and y axes define a plane that is referred to as the xy plane. Given each axis, choose a unit length, and mark off each unit along the axis, forming a grid. To specify a particular point on a two dimensional coordinate system, indicate the x unit first (abscissa), followed by the y unit (ordinate) in the form (x,y), an ordered pair.

The choice of letters comes from a convention, to use the latter part of the alphabet to indicate unknown values. In contrast, the first part of the alphabet was used to designate known values.

An example of a point P on the system is indicated in Figure 3, using the coordinate (3,5).

The intersection of the two axes creates four regions, called quadrants, indicated by the Roman numerals I, II, III, and IV. Conventionally, the quadrants are labeled counter-clockwise starting from the upper right ("northeast") quadrant. In the first quadrant, both coordinates are positive, in the second quadrant x-coordinates are negative and y-coordinates positive, in the third quadrant both coordinates are negative and in the fourth quadrant, x-coordinates are positive and y-coordinates negative (see table below.)

| Quadrant | x-values | y-values |

|---|---|---|

| I | > 0 | > 0 |

| II | < 0 | > 0 |

| III | < 0 | < 0 |

| IV | > 0 | < 0 |

Three-dimensional coordinate system

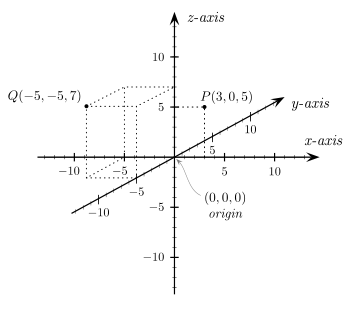

The three dimensional coordinate system provides the three physical dimensions of space — height, width, and length. Figures 4 and 5, below, show two common ways of representing the three-dimensional coordinate system.

The coordinates in a three dimensional system are of the form (x,y,z). As an example, two points are plotted in this system in Figure 4, points P(3,0,5) and Q(−5,−5,7). The axes are depicted in a world-coordinates orientation with the z-axis pointing up.

The x-, y-, and z-coordinates of a point can also be taken as the distances from the yz-plane, xz-plane, and xy-plane respectively. Figure 5 shows the distances of point P from the planes.

The xy-, yz-, and xz-planes divide the three-dimensional space into eight subdivisions known as octants, similar to the quadrants of 2D space. While conventions have been established for the labeling of the four quadrants of the x-y plane, only the first octant of three dimensional space is labeled. It contains all of the points whose x, y, and z coordinates are positive.

Orientation and "handedness"

- see also: right-hand rule

In two dimensions

Fixing or choosing the x-axis determines the y-axis up to direction. Namely, the y-axis is necessarily the perpendicular to the x-axis through the point marked 0 on the x-axis. But there is a choice of which of the two half lines on the perpendicular to designate as positive and which as negative. Each of these two choices determines a different orientation of the Cartesian plane. The standard way of orienting the axes, with the positive x-axis pointing right and the positive y-axis pointing up (and the x-axis being the "first" and the y-axis the "second" axis) is considered the positive or standard orientation. Rotating the coordinate system will preserve the orientation. Switching the role of x and y will reverse the orientation.

A commonly used mnemonic is the right hand rule. Placing a somewhat closed right hand on the plane with the thumb pointing up, the fingers point from the x-axis to the y-axis, in a positively oriented coordinate system.

In three dimensions

Once the x- and y-axes are specified, they determine the line along which the z-axis should lie, but there are two possible directions on this line. The two possible coordinate systems which result are called 'right-handed' and 'left-handed'. The standard orientation, where the xy-plane is horizontal and the z-axis points up (and the x- and the y-axis form a positively oriented two-dimensional coordinate system in the xy-plane if observed from above the xy-plane) is called right-handed or positive.

The name derives from the right-hand rule. If the index finger of the right hand is pointed forward, the middle finger bent inward at a right angle to it, and the thumb placed at a right angle to both, the three fingers indicate the relative directions of the x-, y-, and z-axes in a right-handed system. The thumb indicates the x-axis, the index finger the y-axis and the middle finger the z-axis. Conversely, if the same is done with the left hand, a left-handed system results.

Different disciplines use different variations of the coordinate systems. For example, mathematicians typically use a right-handed coordinate system with the y-axis pointing up, while engineers typically use a left-handed coordinate system with the z-axis pointing up. This has the potential to lead to confusion when engineers and mathematicians work on the same project.

Figure 6 is an attempt at depicting a left- and a right-handed coordinate system. Because a three-dimensional object is represented on the two-dimensional screen, distortion and ambiguity result. The axis pointing downward (and to the right) is also meant to point towards the observer, whereas the "middle" axis is meant to point away from the observer. The red circle is parallel to the horizontal xy-plane and indicates rotation from the x-axis to the y-axis (in both cases). Hence the red arrow passes in front of the z-axis.

Figure 7 is another attempt at depicting a right-handed coordinate system. Again, there is an ambiguity caused by projecting the three-dimensional coordinate system into the plane. Many obervers see Figure 7 as "flipping in and out" between a convex cube and a concave "corner". This corresponds to the two possible orientations of the coordinate system. Seeing the figure as convex gives a left-handed coordinate system. Thus the "correct" way to view Figure 7 is to imagine the x-axis as pointing towards the observer and thus seeing a concave corner.

In physics

The above discussion applies to Cartesian coordinate systems in mathematics, where it is common to not use any units of measurement. In physics it is important to note that a dimension is simply a measure of something, and that, for each class of features to be measured, another dimension can be added. Attachment to visualising the dimensions precludes understanding the many different dimensions that can be measured (time, mass, color, cost, etc.). Multi-dimensional objects can be calculated and manipulated algebraically.

Further notes

In analytic geometry the Cartesian coordinate system is the foundation for the algebraic manipulation of geometrical shapes. Many other coordinate systems have been developed since Descartes. One common set of systems use polar coordinates; astronomers often use spherical coordinates, a type of polar coordinate system. In different branches of mathematics coordinate systems can be transformed, translated, rotated, and re-defined altogether to simplify calculation and for specialised ends.

It may be interesting to note that some have indicated that the master artists of the Renaissance used a grid, in the form of a wire mesh, as a tool for breaking up the component parts of their subjects they painted. That this may have influenced Descartes is merely speculative. (See perspective, projective geometry.)

See also

- List of canonical coordinate transformations

- Graph of a function

- Point plotting

- Point (geometry)

- Line (mathematics)

- Plane (mathematics)

- Complex plane

- Right-hand rule

- Orientation (mathematics)

- Regular grid

- Integer point

Other coordinate systems

- Coordinates (mathematics)

- Coordinate systems

- Polar coordinate system

- Taxicab geometry

- Curvilinear coordinates

- Hyperbolic coordinates

- Stereographic projection

- Parallel coordinates

- Geocentric coordinates

History

Examples

- Circle

- Unit circle

- Ellipse

- Hyperbola

- Parabola

- Lemniscate

- Hyperbolic spiral

- Kappa curve

- Derivation of the cartesian formula for an ellipse

- Spring (math)

- Super ellipse

- Cylinder (geometry)

- Ellipsoid

Context

- Ordered pair

- Analytic geometry

- Abstraction (mathematics)

- Address (geography)

- Notation system

- ISO 31-1

- Mathematics and architecture

- Graph paper

References

Descartes, René. Oscamp, Paul J. (trans). Discourse on Method, Optics, Geometry, and Meteorology. 2001.

External links

- Graph Paper

- Cartesian Coordinate System

- Graph Mole- Play Graph Mole, a free online game at FunBasedLearning.com, to learn how to plot points on the Cartesian coordinate plane.

- Interactive Cartesian Coordinates from Math Is Fun