User:SydneyDale/sandbox: Difference between revisions

SydneyDale (talk | contribs) m cited 2 more sources |

SydneyDale (talk | contribs) added a source- added new information to 'genres' and 'contributors'. Tags: Possible self promotion in userspace Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

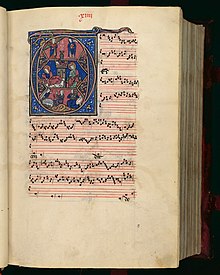

[[File:Magnus Liber Organi.jpg|thumb|Folio 8 of Manuscript F]] |

|||

The '''''Magnus Liber''''' or '''''Magnus liber organi''''' (English translation: '''''Great Book of Organum'''''), written in [[Latin]], was a repertory of [[medieval music]] known as [[organum]]. This collection of organum survives today in 3 major manuscripts. This repertoire was in use by the [[Notre-Dame school]] [[Composer|composers]] working in [[Paris]] around the end of the 12th and beginning of the 13th centuries, though it is well agreed upon by scholars that Leonin contributed a bulk of the organum in the repertoire. This large body of repertoire is known from references to a ''"magnum volumen"'' by [[Johannes de Garlandia (music theorist)|Johannes de Garlandia]] and to a ''"Magnus liber organi de graduali et antiphonario pro servitio divino"'' by the [[England|English]] music theorist known simply as [[Anonymous IV]]. Today it is known only from later manuscripts containing compositions named in Anonymous IV's description. The ''Magnus liber'' is regarded as the earliest collection of polyphony, and is therefore regarded highly in the studies of musicology and music history. |

The '''''Magnus Liber''''' or '''''Magnus liber organi''''' (English translation: '''''Great Book of Organum'''''), written in [[Latin]], was a repertory of [[medieval music]] known as [[organum]]. This collection of organum survives today in 3 major manuscripts. This repertoire was in use by the [[Notre-Dame school]] [[Composer|composers]] working in [[Paris]] around the end of the 12th and beginning of the 13th centuries, though it is well agreed upon by scholars that [[Leonin]] contributed a bulk of the organum in the repertoire. This large body of repertoire is known from references to a ''"magnum volumen"'' by [[Johannes de Garlandia (music theorist)|Johannes de Garlandia]] and to a ''"Magnus liber organi de graduali et antiphonario pro servitio divino"'' by the [[England|English]] music theorist known simply as [[Anonymous IV]]. Today it is known only from later manuscripts containing compositions named in Anonymous IV's description. The ''Magnus liber'' is regarded as the earliest collection of polyphony, and is therefore regarded highly in the studies of musicology and music history. |

||

== Surviving Manuscripts == |

== Surviving Manuscripts == |

||

The ''Magnus liber organi'' is considered most likely to have originated in Paris, and is known today by only a few surviving manuscripts and fragments, and there are records of at least seventeen lost versions. <ref name=":0" /> Today its contents can be inferred from the 3 surviving major manuscripts: |

The ''Magnus liber organi'' is considered most likely to have originated in Paris, and is known today by only a few surviving manuscripts and fragments, and there are records of at least seventeen lost versions. <ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Baltzer|first=Rebecca A.|date=1987|title=Notre Dame Manuscripts and Their Owners: Lost and Found|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/763698|journal=Journal of Musicology|volume=5|issue=3|pages=380–399|doi=10.2307/763698|issn=0277-9269}}</ref> Today its contents can be inferred from the 3 surviving major manuscripts: |

||

* '''Florence Manuscript [F]''' (I-Fl [[Pluteo 29.1]], [[Laurentian Library|Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence]]) |

* '''Florence Manuscript [F]''' (I-Fl [[Pluteo 29.1]], [[Laurentian Library|Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence]]) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 9: | ||

* '''Wolfenbüttel 1099 [W2]''' (Wolfenbüttel Cod. Guelf. Helmst 1099) |

* '''Wolfenbüttel 1099 [W2]''' (Wolfenbüttel Cod. Guelf. Helmst 1099) |

||

"Evidence of lost Notre Dame manuscripts, including the names of their owners, is plentiful indeed" <ref name=":0" />, tracing back to year 1456 when manscript '''F''' first appeared in the library of [[Piero di Cosimo de' Medici|Piero de' Medici]]. Of the two others, referred to as '''W1''' & '''W2''', both in the [[Herzog August Library|Herzog August Bibliothek (Ducal Library)]], the first is thought to have originated in the cathedral priory of St Andrews, Scotland, and less is known about '''W2.''' The Ma fragment (Madrid 20486) is, believed to be originally from Toledo. Catalogues referring to other lost copies attest to the wide diffusion through Western Europe of the repertoire later called ''[[ars antiqua]]''. |

These three manuscripts date from a time much later than the original ''Magnus liber,'' but the careful study by many scholars has revealed many details regarding origin and development.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Smith|first=Norman E.|date=1973|title=Interrelationships among the Graduals of the Magnus Liber Organi|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/932223|journal=Acta Musicologica|volume=45|issue=1|pages=73–97|doi=10.2307/932223|issn=0001-6241}}</ref> "Evidence of lost Notre Dame manuscripts, including the names of their owners, is plentiful indeed" <ref name=":0" />, tracing back to year 1456 when manscript '''F''' first appeared in the library of [[Piero di Cosimo de' Medici|Piero de' Medici]]. Of the two others, referred to as '''W1''' & '''W2''', both in the [[Herzog August Library|Herzog August Bibliothek (Ducal Library)]], the first is thought to have originated in the cathedral priory of St Andrews, Scotland, and less is known about '''W2.''' The Ma fragment (Madrid 20486) is, believed to be originally from Toledo. Catalogues referring to other lost copies attest to the wide diffusion through Western Europe of the repertoire later called ''[[ars antiqua]]''. |

||

Heinrich Husmann summarizes that 'these manuscripts, then, do not represent any more the original state of the ''Magnus liber,'' but rather enlarged forms of it, differing from each other. In fact, these manuscripts embody different stylistic developments of the ''Magnus liber'' itself, particularly in the field of composition mentioned by Anonymous IV, the [[Clausula (music)|clausula]]. This is born out by the differing versions of the discantus parts." <ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Husmann|first=Heinrich|last2=Briner|first2=Andres P.|date=1963|title=The Enlargement of the Magnus liber organi and the Paris Churches St. Germain l'Auxerrois and Ste. Geneviève-du-Mont|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/829940|journal=Journal of the American Musicological Society|volume=16|issue=2|pages=176–203|doi=10.2307/829940|issn=0003-0139}}</ref> Husmann also notes that a comparison of the repertory contained in the three manuscripts shows that there 'are a great many pieces common to all three sources' and that 'the most reasonable attitude is obviously to consider the pieces in common to all three sources as the original body, consequently as the true ''Magnus liber organi.''<nowiki/>'<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

== Contributors to the Liber == |

== Contributors to the Liber == |

||

It is unknown whether the the ''Liber'' had one sole contributor, though it is noted by scholars that large parts were composed by [[Léonin]] (1135–c.1200). Though it is a controversial topic among scholars, some believe parts of the ''Magnus liber organi'' may have revised by [[Pérotin]] (fl. 1200). |

It is unknown whether the the ''Liber'' had one sole contributor, though it is noted by scholars that large parts were composed by [[Léonin]] (1135–c.1200). Though it is a controversial topic among scholars, some believe parts of the ''Magnus liber organi'' may have revised by [[Pérotin]] (fl. 1200), while others such as Heinrich Husmann note that the finding is from 'the rather slim report of Anonymous IV' and 'as for its connections with Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the name of Perotin alone is adduced' in connection with his books having only been ''used''. This 'by no means confirms that Perotin himself was active at Notre Dame, or anywhere else in Paris for that matter' <ref name=":3" />. |

||

The music from the ''Liber'' has been published in modern times by [[William Waite]] (1954), [[Hans Tischler]] (1989) and by Edward Roesner (1993–2009). |

The music from the ''Liber'' has been published in modern times by [[William Waite]] (1954), [[Hans Tischler]] (1989) and by Edward Roesner (1993–2009). |

||

| Line 18: | Line 21: | ||

The [[early music]] of Notre Dame cathedral represents a transitional time for Western culture. Coinciding with the architectural innovation that produced the structure of the Cathedral itself, from the beginning of its construction in 1163. A handful of surviving manuscripts demonstrate the evolution of [[Polyphony|polyphonic]] elaboration of the liturgical [[plainchant]] that was used at the cathedral every day throughout the year. While the concept of combining voices in harmony to enrich plainsong chant was not new, there lacked the established and codified [[Music theory|musical theory]] techniques to enable the rational construction of such pieces. |

The [[early music]] of Notre Dame cathedral represents a transitional time for Western culture. Coinciding with the architectural innovation that produced the structure of the Cathedral itself, from the beginning of its construction in 1163. A handful of surviving manuscripts demonstrate the evolution of [[Polyphony|polyphonic]] elaboration of the liturgical [[plainchant]] that was used at the cathedral every day throughout the year. While the concept of combining voices in harmony to enrich plainsong chant was not new, there lacked the established and codified [[Music theory|musical theory]] techniques to enable the rational construction of such pieces. |

||

The ''Magnus Liber'' represents a step in the evolution of [[Classical music|Western music]] between [[plainchant]] and the intricate [[polyphony]] of the later 13th and 14th centuries (see [[Guillaume de Machaut|Machaut]] and [[Ars Nova]]). The music of the ''Magnus Liber'' displays a connection to the emerging [[Gothic architecture|Gothic]] style of architecture; just as ornate [[Cathedral|cathedrals]] were built to house holy [[Relic|relics]], organa were written to elaborate [[Gregorian chant]], which too was considered holy. |

|||

The innovations at Notre Dame consisted of a system of [[musical notation]] which included patterns of short and long [[musical notes]] known as longs and [[Double whole note|breves]]. This system is referred to mensural music as it demonstrates the beginning of 'measured time' in music, organizing lengths of pitches within plainchant and later, the [[motet]] genre. |

|||

The |

The innovations at Notre Dame consisted of a system of [[musical notation]] which included patterns of short and long [[musical notes]] known as longs and [[Double whole note|breves]]. This system is referred to as mensural music as it demonstrates the beginning of 'measured time' in music, organizing lengths of pitches within plainchant and later, the [[motet]] genre. In the organi of the ''Magnus liber,'' one voice sang the notes of the Gregorian chant elongated to enormous length called the tenor (from Latin 'to hold'), but was also known as the ''vox principalis.'' As many as three voices, known as the ''vox organalis'' (or ''vinnola vox'', the "vining voice") were notated above the tenor, with quicker lines moving and weaving together, a style also known as ''florid organum'' <ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Bradley|first=Catherine A.|date=2019|title=Choosing a Thirteenth-Century Motet Tenor: From the Magnus Liber Organi to Adam De La Halle|url=|journal=Journal of the American Musicological Society|volume=72|pages=431-492|via=JSTOR}}</ref>. The evolution from a single line of music ([[monophony]]) to one where multiple lines all carried the same weight ([[polyphony]]) is shown through the writing of organa. The practice of keeping a slow moving "tenor" line continued into secular music, and the words of the original chant survived in some cases as well. One of the most common types of organa in the ''Magnus Liber'' is the [[Clausula (music)|clausula]], which are "sections where, in [[Discant|discantus]] style, the tenor uses rhythmic patterns as well as the upper part" <ref name=":2" />. These sections of polyphony were substituted into longer organa. The extant manuscripts provide a number of notational challenges to modern practice, since they contain only the polyphonic elements, from which the chant has to be inferred. |

||

The music of the ''Magnus Liber'' was used in the [[liturgy]] of the church throughout the feasts of the church year. The text contains only the polyphonic lines and the notation is not exact, as barlines were still several centuries from invention. The chant was added to the notated music, and it was up to the performers to fit the disparate lines together into a coherent whole, meaning even an instrument could have been used to represent the tenor line. |

The music of the ''Magnus Liber'' was used in the [[liturgy]] of the church throughout the feasts of the church year. The text contains only the polyphonic lines and the notation is not exact, as barlines were still several centuries from invention. The chant was added to the notated music, and it was up to the performers to fit the disparate lines together into a coherent whole, meaning even an instrument could have been used to represent the tenor line. |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

{{dashboard.wikiedu.org sandbox}} |

|||

{{dashboard.wikiedu.org sandbox}}<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Baltzer|first=Rebecca A.|date=1987|title=Notre Dame Manuscripts and Their Owners: Lost and Found|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/763698|journal=Journal of Musicology|volume=5|issue=3|pages=380–399|doi=10.2307/763698|issn=0277-9269}}</ref>ladeeedadeee |

|||

<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Bradley|first=Catherine A.|date=2019|title=Choosing a Thirteenth-Century Motet Tenor: From the Magnus Liber Organi to Adam De La Halle|url=|journal=Journal of the American Musicological Society|volume=72|pages=431-492|via=JSTOR}}</ref> dooodeeeedooo |

|||

<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Husmann|first=Heinrich|last2=Briner|first2=Andres P.|date=1963|title=The Enlargement of the Magnus liber organi and the Paris Churches St. Germain l'Auxerrois and Ste. Geneviève-du-Mont|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/829940|journal=Journal of the American Musicological Society|volume=16|issue=2|pages=176–203|doi=10.2307/829940|issn=0003-0139}}</ref> do re mi |

|||

<ref>{{Cite journal|last=HUSMANN|first=HEINRICH|date=1963|title=THE ORIGIN AND DESTINATION OF THE MAGNUS LIBER ORGANI|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mq/xlix.3.311|journal=The Musical Quarterly|volume=XLIX|issue=3|pages=311–330|doi=10.1093/mq/xlix.3.311|issn=0027-4631}}</ref>fa sol la |

<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=HUSMANN|first=HEINRICH|date=1963|title=THE ORIGIN AND DESTINATION OF THE MAGNUS LIBER ORGANI|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mq/xlix.3.311|journal=The Musical Quarterly|volume=XLIX|issue=3|pages=311–330|doi=10.1093/mq/xlix.3.311|issn=0027-4631}}</ref>fa sol la |

||

Revision as of 22:20, 30 November 2020

The Magnus Liber or Magnus liber organi (English translation: Great Book of Organum), written in Latin, was a repertory of medieval music known as organum. This collection of organum survives today in 3 major manuscripts. This repertoire was in use by the Notre-Dame school composers working in Paris around the end of the 12th and beginning of the 13th centuries, though it is well agreed upon by scholars that Leonin contributed a bulk of the organum in the repertoire. This large body of repertoire is known from references to a "magnum volumen" by Johannes de Garlandia and to a "Magnus liber organi de graduali et antiphonario pro servitio divino" by the English music theorist known simply as Anonymous IV. Today it is known only from later manuscripts containing compositions named in Anonymous IV's description. The Magnus liber is regarded as the earliest collection of polyphony, and is therefore regarded highly in the studies of musicology and music history.

Surviving Manuscripts

The Magnus liber organi is considered most likely to have originated in Paris, and is known today by only a few surviving manuscripts and fragments, and there are records of at least seventeen lost versions. [1] Today its contents can be inferred from the 3 surviving major manuscripts:

- Florence Manuscript [F] (I-Fl Pluteo 29.1, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence)

- Wolfenbüttel 677 [W1] (Wolfenbüttel Cod. Guelf. Helmst. 677)

- Wolfenbüttel 1099 [W2] (Wolfenbüttel Cod. Guelf. Helmst 1099)

These three manuscripts date from a time much later than the original Magnus liber, but the careful study by many scholars has revealed many details regarding origin and development.[2] "Evidence of lost Notre Dame manuscripts, including the names of their owners, is plentiful indeed" [1], tracing back to year 1456 when manscript F first appeared in the library of Piero de' Medici. Of the two others, referred to as W1 & W2, both in the Herzog August Bibliothek (Ducal Library), the first is thought to have originated in the cathedral priory of St Andrews, Scotland, and less is known about W2. The Ma fragment (Madrid 20486) is, believed to be originally from Toledo. Catalogues referring to other lost copies attest to the wide diffusion through Western Europe of the repertoire later called ars antiqua.

Heinrich Husmann summarizes that 'these manuscripts, then, do not represent any more the original state of the Magnus liber, but rather enlarged forms of it, differing from each other. In fact, these manuscripts embody different stylistic developments of the Magnus liber itself, particularly in the field of composition mentioned by Anonymous IV, the clausula. This is born out by the differing versions of the discantus parts." [3] Husmann also notes that a comparison of the repertory contained in the three manuscripts shows that there 'are a great many pieces common to all three sources' and that 'the most reasonable attitude is obviously to consider the pieces in common to all three sources as the original body, consequently as the true Magnus liber organi.'[3]

Contributors to the Liber

It is unknown whether the the Liber had one sole contributor, though it is noted by scholars that large parts were composed by Léonin (1135–c.1200). Though it is a controversial topic among scholars, some believe parts of the Magnus liber organi may have revised by Pérotin (fl. 1200), while others such as Heinrich Husmann note that the finding is from 'the rather slim report of Anonymous IV' and 'as for its connections with Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the name of Perotin alone is adduced' in connection with his books having only been used. This 'by no means confirms that Perotin himself was active at Notre Dame, or anywhere else in Paris for that matter' [4].

The music from the Liber has been published in modern times by William Waite (1954), Hans Tischler (1989) and by Edward Roesner (1993–2009).

Styles and Genres of the Repertoire

The early music of Notre Dame cathedral represents a transitional time for Western culture. Coinciding with the architectural innovation that produced the structure of the Cathedral itself, from the beginning of its construction in 1163. A handful of surviving manuscripts demonstrate the evolution of polyphonic elaboration of the liturgical plainchant that was used at the cathedral every day throughout the year. While the concept of combining voices in harmony to enrich plainsong chant was not new, there lacked the established and codified musical theory techniques to enable the rational construction of such pieces.

The Magnus Liber represents a step in the evolution of Western music between plainchant and the intricate polyphony of the later 13th and 14th centuries (see Machaut and Ars Nova). The music of the Magnus Liber displays a connection to the emerging Gothic style of architecture; just as ornate cathedrals were built to house holy relics, organa were written to elaborate Gregorian chant, which too was considered holy.

The innovations at Notre Dame consisted of a system of musical notation which included patterns of short and long musical notes known as longs and breves. This system is referred to as mensural music as it demonstrates the beginning of 'measured time' in music, organizing lengths of pitches within plainchant and later, the motet genre. In the organi of the Magnus liber, one voice sang the notes of the Gregorian chant elongated to enormous length called the tenor (from Latin 'to hold'), but was also known as the vox principalis. As many as three voices, known as the vox organalis (or vinnola vox, the "vining voice") were notated above the tenor, with quicker lines moving and weaving together, a style also known as florid organum [5]. The evolution from a single line of music (monophony) to one where multiple lines all carried the same weight (polyphony) is shown through the writing of organa. The practice of keeping a slow moving "tenor" line continued into secular music, and the words of the original chant survived in some cases as well. One of the most common types of organa in the Magnus Liber is the clausula, which are "sections where, in discantus style, the tenor uses rhythmic patterns as well as the upper part" [3]. These sections of polyphony were substituted into longer organa. The extant manuscripts provide a number of notational challenges to modern practice, since they contain only the polyphonic elements, from which the chant has to be inferred.

The music of the Magnus Liber was used in the liturgy of the church throughout the feasts of the church year. The text contains only the polyphonic lines and the notation is not exact, as barlines were still several centuries from invention. The chant was added to the notated music, and it was up to the performers to fit the disparate lines together into a coherent whole, meaning even an instrument could have been used to represent the tenor line.

References

| This is a user sandbox of SydneyDale. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

[4]fa sol la

- ^ a b Baltzer, Rebecca A. (1987). "Notre Dame Manuscripts and Their Owners: Lost and Found". Journal of Musicology. 5 (3): 380–399. doi:10.2307/763698. ISSN 0277-9269.

- ^ Smith, Norman E. (1973). "Interrelationships among the Graduals of the Magnus Liber Organi". Acta Musicologica. 45 (1): 73–97. doi:10.2307/932223. ISSN 0001-6241.

- ^ a b c Husmann, Heinrich; Briner, Andres P. (1963). "The Enlargement of the Magnus liber organi and the Paris Churches St. Germain l'Auxerrois and Ste. Geneviève-du-Mont". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 16 (2): 176–203. doi:10.2307/829940. ISSN 0003-0139.

- ^ a b HUSMANN, HEINRICH (1963). "THE ORIGIN AND DESTINATION OF THE MAGNUS LIBER ORGANI". The Musical Quarterly. XLIX (3): 311–330. doi:10.1093/mq/xlix.3.311. ISSN 0027-4631.

- ^ Bradley, Catherine A. (2019). "Choosing a Thirteenth-Century Motet Tenor: From the Magnus Liber Organi to Adam De La Halle". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 72: 431–492 – via JSTOR.