Fernando Botero

Fernando Botero | |

|---|---|

Botero in 2006 | |

| Born | Fernando Botero Angulo[1] 19 April 1932 Medellín, Colombia |

| Known for | Painter, sculptor |

| Notable work | Mona Lisa, Age Twelve (1959), Pope Leo X (after Raphael) (1964), The Presidential Family (1967), The Dancers (1987), Death of Pablo Escobar (1999), Abu Ghraib series (2005) |

| Spouses |

|

Fernando Botero Angulo (born 19 April 1932) is a Colombian figurative artist and sculptor, born in Medellín. His signature style, also known as "Boterismo", depicts people and figures in large, exaggerated volume, which can represent political criticism or humor, depending on the piece. He is considered the most recognized and quoted living artist from Latin America,[2][3][4] and his art can be found in highly visible places around the world, such as Park Avenue in New York City and the Champs-Élysées in Paris.[5]

Self-titled "the most Colombian of Colombian artists" early on, Botero came to national prominence when he won the first prize at the Salón de Artistas Colombianos in 1958. He began creating sculptures after moving to Paris in 1973, achieving international recognition with exhibitions around the world by the 1990s.[6][7] His art is collected by many major international museums, corporations, and private collectors. In 2012, he received the International Sculpture Center's Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award.[8]

Biography

Early life

Fernando Botero was born as the second of three sons of David Botero (1895–1936) and Flora Angulo (1898–1972) in 1932. His father David Botero, a salesman who traveled by horseback, died of a heart attack when Fernando was four. His mother worked as a seamstress. An uncle took a major role in his life. Although isolated from art as presented in museums and other cultural institutes, Botero was influenced by the Baroque style of the colonial churches and the city life of Medellín while growing up.[9]

He received his primary education in Antioquia Ateneo and, thanks to a scholarship, he continued his secondary education at the Jesuit School of Bolívar.[10] In 1944, Botero's uncle sent him to a school for matadors for two years.[11] In 1948, Botero at the age of 16 had his first illustrations published in the Sunday supplement of El Colombiano, one of the most important newspapers in Medellín. He used the money he was paid to attend high school at the Liceo de Marinilla de Antioquia.

Career

Botero's work was first exhibited in 1948, in a group show along with other artists from the region.[12] From 1949 to 1950, Botero worked as a set designer, before moving to Bogotá in 1951. His first one-man show was held at the Galería Leo Matiz in Bogotá, a few months after his arrival. In 1952, Botero travelled with a group of artists to Barcelona, where he stayed briefly before moving on to Madrid.

In Madrid, Botero studied at the Academia de San Fernando.[13] In 1952, he traveled to Bogotá, where he had a solo exhibition at the Leo Matiz gallery.

In 1953, Botero moved to Paris, where he spent most of his time in the Louvre, studying the works there. He lived in Florence, Italy from 1953 to 1954, studying the works of Renaissance masters.[12] In recent decades, he has lived most of the time in Paris, but spends one month a year in his native city of Medellín. He has had more than 50 exhibitions in major cities worldwide, and his work commands selling prices in the millions of dollars.[14] In 1958, he won the ninth edition of the Salón de Artistas Colombianos.[15]

In 2004, Botero exhibited a series of 27 drawings and 23 paintings dealing with the violence in Colombia from 1999 through 2004. He donated the works to the National Museum of Colombia, where they were first exhibited.[16]

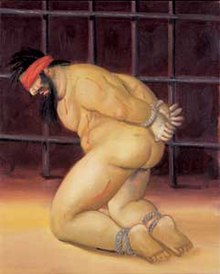

In 2005, Botero gained considerable attention for his Abu Ghraib series, which was exhibited first in Europe. He based the works on reports of United States forces' abuses of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War. Beginning with an idea he had on a plane journey, Botero produced more than 85 paintings and 100 drawings in exploring this concept[17] and "painting out the poison".[14] The series was exhibited at two United States locations in 2007, including Washington, DC. Botero said he would not sell any of the works, but would donate them to museums.[18] In 2009, the Berkeley Art Museum acquired (as a gift from the artist) 56 paintings and drawings from the Abu Ghraib series, which can be seen online.[19] Selections from the series have been regularly included in the museum's annual Art for Human Rights exhibitions.[20]

In 2006, after having focused exclusively on the Abu Ghraib series for over 14 months, Botero returned to the themes of his early life such as the family and maternity. In his Une Famille[21] Botero represented the Colombian family, a subject often painted in the seventies and eighties. In his Maternity,[22] Botero repeated a composition he already painted in 2003,[23] being able to evoke a sensuous velvety texture that lends it a special appeal and testifies for a personal involvement of the artist. The child in the 2006 drawing has a wound in his right chest, as though the artist wished to identify him with Jesus Christ, thus giving it a religious meaning that was absent in the 2003 artwork.

In 2008, he exhibited the works of his The Circus collection, featuring 20 works in oil and watercolor. In a 2010 interview, Botero said that he was ready for other subjects: "After all this, I always return to the simplest things: still lifes."[14]

Style

While his work includes still-lifes and landscapes, Botero has concentrated on situational portraiture. His paintings and sculptures are united by their proportionally exaggerated, or "fat" figures, as he once referred to them.[14] Botero explains his use of these "large people", as they are often called by critics, in the following way:

"An artist is attracted to certain kinds of form without knowing why. You adopt a position intuitively; only later do you attempt to rationalize or even justify it."[24][self-published source?]

Though he spends only one month a year in Colombia, he considers himself the "most Colombian artist living", due to his isolation from the international trends of the art world.[14]

Sculpture

Between 1963 and 1964, Fernando Botero attempted to create sculptures. Due to financial constraints preventing him from working with bronze, he made his sculptures with acrylic resin and sawdust. A notable example during this time was Small Head (Bishop) in 1964, a sculpture painted with great realism. However, the material was too porous, and Botero decided to abandon this method.

Donations

Botero has donated several artworks to museums in Bogotá and his hometown, Medellín. In 2000, Botero donated to the Museo Botero in Bogota 123 pieces of his work and 85 pieces from his personal collection, including works by Chagall, Picasso, Robert Rauschenberg, and the French impressionists.[25] He donated 119 pieces to the Museum of Antioquia.[26] His donation of 23 bronze sculptures for the front of the museum became known as the Botero Plaza. Four more sculptures can be found in Medellín's Berrio Park and San Antonio Plaza nearby.

In response to the Colombian peace process, Botero sculptured and donated La paloma de la paz (2016) to the Government of Colombia to commemorate the signing and ratification of the agreement.

Personal life

Botero married Gloria Zea, who became the director of the Colombian Institute of Culture (Colcultura). Together they had three children: Fernando, Lina, and Juan Carlos.[10] The Boteros divorced in 1960 and each remarried.[15] Starting in 1960, Botero lived for 14 years in New York, but more recently has settled in Paris. Lina also lives outside of Colombia, and in 2000 Juan Carlos moved to southern Florida.

In 1964, Botero began living with Cecilia Zambrano. They had a son, born in 1974, who was killed in 1979 in a car accident in which Botero was also injured. Botero and Zambrano separated in 1975.[15][27]

Fernando Botero married the Greek artist Sophia Vari. They resided in Paris and Monte Carlo and also had a house in Pietrasanta, Italy.[27] Botero's 80th birthday was commemorated with an exhibition of his works at Pietrasanta.[28] Vari died in 2023.[citation needed]

Popular culture

Botero's 1964 painting Pope Leo X (after Raphael) has found a second life as a popular internet meme. It is typically seen with the caption "y tho".[29][30][31][32]

Recent exhibitions

- "Fund-Raiser" Exhibition with Sonia Falcone at Calvin Charles Gallery[33] (2003), Scottsdale, Arizona

- "Botero at Ebisu" (2004), Tokyo

- "Fernando Botero" (2006), Athens

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (2007), Quebec City

- "Abu Ghraib Exhibit" (2007), University of California, Berkeley

- "Botero: Abu Ghraib" (6 November – 30 December 2007), American University Museum

- "Botero Abu Ghraib" Exposition (2008), Centro de las Artes I Monterrey, Mexico

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (May 2008), Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (28 June – 21 September 2008), New Orleans Museum of Art

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (30 May – 16 August 2009), Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (19 October – 11 January 2009), Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tennessee

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (12 September 2009 – 6 December 2009), Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, California[34]

- "Fernando Botero" (September 2009) Korea, Seoul, Bandi Gallery

- "Fernando Botero: Works On Paper, Paintings, and Sculptures" (11 February – 28 March 2010), David Benrimon Fine Art, New York, NY[35]

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (1 May – 25 July 2010), Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada

- "Botero" (4 May – 18 July 2010), Pera Museum, Istanbul[36]

- "Botero in LA" (15 September - 30 October 2010), Tasende Gallery, West Hollywood, California, USA

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (21 August – 14 November 2010), Glenbow Museum, Calgary

- "The Baroque World of Fernando Botero" (10 December 2010 – 27 February 2011), Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg

- "Botero" (October 2011 – January 2012), Kunstforum, Vienna

- "Fernando Botero" (July 2015 – October 2015), Seoul Arts Center, Seoul

- "Botero in China" (November 2015 – January 2016), The National Museum of China, Beijing

- "Botero in China" (January 2016 – April 2016), China Art Museum, Shanghai

- "Botero: Celebrate Life!" (July 2016 – September 2016), Kunsthal Rotterdam, Netherlands

- "Botero on Lincoln Road" (November 2019 - March 2020), Nader Museum, Miami, Florida [37]

- "Permanent Collection" (Present), NAMLA [38]

Gallery

-

Exhibition in Berlin

-

Cat, 1990, Barcelona, Spain

-

Motherhood, Oviedo, Spain

-

Woman with Mirror, 1987

-

Woman with cigarette, Yerevan

-

Bird, 1990, in front of UOB Plaza, Singapore

-

Roman Warrior, Cafesjian Museum of Art, Yerevan, Armenia

-

Man on Horse, bronze, 1992, at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

-

"The Cat", Yerevan, Armenia

-

The Hand, Madrid, Spain

-

Smoking woman, Cafesjian Museum of Art, Yerevan, Armenia

-

Caballo con bridas, Bilbao

-

Adam and Eve, near Crockfords Tower at Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore

-

Lady, Medellín

-

Sculpture by Fernando Botero in Goslar

-

Sculpture by Fernando Botero in front of the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz

-

Broadgate Venus, 1989, London

-

Cat, Cafesjian Museum of Art, Yerevan, Armenia

-

The Family

-

Fernando Botero's fresco in the Misericordia church in Pietrasanta, Lucca, Italy.

See also

- Adam (Botero), Seattle

- Botero (surname) Italian surname

References

- ^ Botero, Fernando, and Cynthia Jaffee McCabe. 1979. Fernando Botero: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 20. OCLC 5680128

- ^ "'Great Crime' at Abu Ghraib Enrages and Inspires an Artist". The New York Times. 8 May 2005. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Oyb, Marina. "Fernando Botero, el aprendiz eterno". Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ TORREÓN, NOTIMEX / EL SIGLO DE (April 2012). "Fernando Botero, el gran artista de Latinoamérica". Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Kristin G. Congdon; Kara Kelley Hallmark (2002). Artists from Latin American Cultures: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-313-31544-2.

- ^ "40 Salon nacional de artistas". Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ "Fernando Botero". Biography. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ www.marlboroughgallery.com, Marlborough Gallery. "Marlborough Gallery – Fernando Botero Receives the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center". marlboroughgallery.com. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Botero's Early Life" Archived 15 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BoteroSA

- ^ a b John Sillevis (2006). The Baroque World of Fernando Botero. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12359-3.

- ^ "Fernando Botero", AskArt

- ^ a b "Fernando Botero", ArtFact

- ^ Hanstein, Mariana (2003). Fernando Botero. Taschen. p. 15. ISBN 9783822821299. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Fernando Botero: at Thomas Gibson Fine Art", LondonNet, 20 September 2010

- ^ a b c "El poder en Colombia: Los cien personajes mas influyentes de Colombia" Archived 27 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, InfoArt, Dinero, 1 May 1995

- ^ "Fernando Botero: Donation and Controversy" Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Great Masters of Art. Retrieved 20 September 2010

- ^ "Abu Ghraib", ZonaEuropa, 13 April 2005

- ^ Erica Jong, Review: "Botero Sees the World's True Heavies at Abu Ghraib", The Washington Post, 4 November 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2010

- ^ "Art Collection – CollectionSpace". webapps.cspace.berkeley.edu.

- ^ "Permanent Accusation: Art for Human Rights". bampfa.org.

- ^ "Family" Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, oil on canvas 2006

- ^ "Maternity" Archived 8 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, drawing 2006

- ^ "Maternity" Archived 8 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, oil on canvas, 2003

- ^ McDermott, Memory (2005). Tea For Two: Natures Apothecary. Lulu.com. p. 167. ISBN 9781413760972. Retrieved 2 July 2016. [self-published source]

- ^ Michael J. LaRosa; Germán R. Mejía (5 April 2012). Colombia: A Concise Contemporary History. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-1-4422-0937-4.

- ^ Lorrain Caputo. VIVA Colombia Adventure Guide. Viva Publishing Network. pp. 624–. ISBN 978-1-937157-05-0.

- ^ a b Godfrey Barker, "Pure Colombian; Fernando Botero is the scourge of critics and the collectors' darling"[permanent dead link], The Evening Standard (London, England), 3 April 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2010

- ^ "Italy's sculpture capital honours Colombian Fernando Botero". www.mysinchew.com. Retrieved 9 February 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "Woman says sending meme response to job rejection email got her an interview". The Independent. 18 July 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Santora, Sara (18 July 2022). "Woman's Hilarious Response to Job Rejection Email Lands Her an Interview". Newsweek. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ ""Y Tho" (Why Though) | Dartmouth Folklore Archive". journeys.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Latu, Dan (17 July 2022). "'If someone sent that to me I would ABSOLUTELY want an interview': Job applicant secures interview after responding to rejection email with meme". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

External links

- Fernando Botero at FMD

- Botero's Cats

- Gallery of Botero's Artwork Archived 12 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Places To Go in Bogotá: Botero Museum Bogotá – video and information

- Contini Art UK

Abu Ghraib series

- A Permanent Accusation on YouTube A short movie on the Abu Ghraib series by Fernando Botero.

- Abu Ghraib: November 6 – December 30, 2007 It has been announced by the Director and Curator of the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center in Washington, D.C. that Botero's paintings will be exhibited there at the end of this year

- Crucified Smurfs Mark Scroggins discusses Botero's series of canvases & drawings based on the reports of prisoner abuse in Abu Ghraib

- Abu Ghraib: January 29 – March 25, 2007 The first US institutional exhibition at UC Berkeley, with a webcast of a conversation between Fernando Botero and Robert Hass on the day of the opening

- Abu Ghraib: October 18 – November 21, 2006 The first US gallery exhibition at the Marlborough in New York

- The Body in Pain this essay by Arthur Danto at The Nation about Botero's Abu Ghraib series, discusses what Danto refers to as "disturbatory art"

- "Botero Sees the World's True Heavies at Abu Ghraib" by Erica Jong at The Washington Post about Botero's Abu Ghraib series

- "Botero's Abu Ghraib Series and the American Consciousness" by Maymanah Farhat at Monthly Review discusses Botero's Abu Ghraib series in the larger context of American art and politics