Gustav-Adolf Schultze

Gustav-Adolf Schultze | |

|---|---|

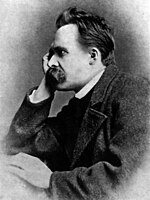

Portrait of Gustav Adolf Schultze, 1872 | |

| Born | 18 December 1825 |

| Died | 1897 (aged 71–72) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | Painter, photographer |

Gustav Adolf Schultze (18 December 1825, in Naumburg, Province of Saxony – 1897 in Almrich) was a German portrait painter.

Life

[edit]Gustav Adolf Schultze was born in 1825, the son of a theologian who later gave up the profession of clergyman and worked as a master needle maker in the Saale / Unstrut district.

After his school years in Naumburg, Gustav Adolf went to Berlin in 1843 to study painting with the then director of the academy, Johann Gottfried Schadow,[1] and then portrait painting with Eduard Magnus.[2] On Schadow's recommendation, Gustav Adolf Schultze met the art historian Franz Theodor Kugler, who became a fatherly friend. Gustav Adolf Schultze was also friendly with the poet Emanuel Geibel, whom he also portrayed. This portrait is now in the Paul Schultze-Naumburg Künstlerheim in Weimar. The writer Paul Heyse also belonged to the circle of friends.

On 12 February 1854, Gustav Adolf Schultze married Emma Louise Emilie Lienemann (1833–1895), a native of Germany. Shortly after the marriage, the couple moved into Lindenring in Naumburg. The young Friedrich Nietzsche was also a frequent guest there. In 1882, he would produce one of Nietzsche's famous portraits.[3] The photo appeared on the French first edition of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.[4]

The marriage entered into in 1854 resulted in six children: a daughter, Emma Fanny Emilie, born in 1854, the eldest son Paul Richard, born in 1855, Max in 1857 and Arthur in 1861. Johanna Katharina Emmy was born in 1867, but she only lived a month. The youngest child Paul Eduard was born in 1869, later known as Paul Schultze-Naumburg.

In addition to portrait painting, Gustav Adolf Schultze also dealt with photography, which had just started at the time. As one of the first artists in this new field, he extended the search for motifs to include sacred buildings. He sought to bring the Naumburgers closer to the artistic treasures of their cathedral. There were technical imperfection of the photographs at that time, and the images from that time have not been preserved.

During the last years of his life, Gustav Adolf Schultze suffered from an eye disease that eventually led to complete blindness. He spent this time on his rural estate in Almrich near Naumburg, where he died in 1897.

His son Paul (1869–1949) became a painter.[1] He started his studies in Karlsruhe and completed them in Munich, where he was a member of the Munich Secession.[1]

Bibliography

[edit]- Norbert Borrmann: Paul Schultze-Naumburg 1869-1949. Maler, Publizist, Architekt. Vom Kulturreformer der Jahrhundertwende zum Kulturpolitiker im Dritten Reich. Ein Lebens- und Zeitdokument Bacht, Essen 1989 ISBN 3-87034-047-9, Page 15

- Stiftung Saalecker Werkstätten: Schriftenreihe Saalecker Werkstätten Heft 1, Mächler, Bad Kösen, 1999, Pages 16–26, ISBN 3-9807603-0-8, See also: Schriftenreihe Archived 2021-09-09 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Uwe Puschner; Walter Schmitz; Justus H. Ulbricht (2012). Ulbricht, Justus H.; Puschner, Uwe; Schmitz, Walter (eds.). Handbuch zur "Völkischen Bewegung" 1871-1918. De Gruyter. p. 925. ISBN 978-3-11-096424-0.

- ^ Norbert Borrmann; Paul Schultze-Naumburg (1989). Paul Schultze-Naumburg, 1869-1949 Maler, Publizist, Architekt : vom Kulturreformer der Jahrhundertwende zum Kulturpolitiker im Dritten Reich: ein Lebens- und Zeitdokument. R. Bacht. p. 203. ISBN 978-3-87034-047-6.

- ^ Flynn, Thomas (2009). Existentialism. Sterling. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4027-6874-3.

- ^ Suárez, Diana Hernández (2021). Fin de siglo Porfirista: arte y política en la Revista Moderna (1898-1911). Editorial Verbum. p. 203. ISBN 978-84-1337-663-9.