Game Theory (band)

Game Theory | |

|---|---|

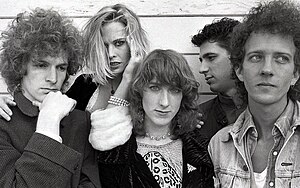

Game Theory publicity photo in 1986 (Scott Miller, Donnette Thayer, Shelley LaFreniere, Guillaume Gassuan, Gil Ray) | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Davis, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Power pop, jangle pop |

| Years active | 1982–1990, 2013, 2016–2017 |

| Labels | Rational, Enigma, Alias, Omnivore |

| Spinoffs | The Loud Family, Hex |

| Spinoff of | Alternate Learning |

| Past members |

|

| Website | www |

Game Theory was an American power pop band, founded in 1982 by singer/songwriter Scott Miller, combining melodic jangle pop with dense experimental production and hyperliterate lyrics. MTV described their sound as "still visceral and vital" in 2013, with records "full of sweetly psychedelic-tinged, appealingly idiosyncratic gems" that continued "influencing a new generation of indie artists."[1] Between 1982 and 1990, Game Theory released five studio albums and two EPs, which had long been out of print until 2014, when Omnivore Recordings began a series of remastered reissues of the entire Game Theory catalog. Miller's posthumously completed Game Theory album, Supercalifragile, was released in August 2017 in a limited first pressing.

Miller was the group's leader and sole constant member, presiding over frequently changing line-ups. During its early years in Davis, California, Game Theory was often associated with the Paisley Underground movement, but remained in northern California, moving to the Bay Area in 1985, while similarly aligned local bands moved to Los Angeles.[2][3]

The group became known for its fusion of catchy musical hooks with musical complexity, as well as for Miller's lyrics that often featured self-described "young-adult-hurt-feeling-athons,"[4] along with literary references (e.g., Real Nighttime's allusions to James Joyce), and pop culture references ranging from Peanuts ("The Red Baron") to Star Trek quotes ("One More for St. Michael").

Musical career

Transition from Alternate Learning (1982)

Prior to founding Game Theory, Scott Miller had been the lead singer and songwriter of Alternate Learning, which issued an EP in 1979 and an LP in 1981. Alternate Learning was based in Sacramento and Davis, California, and frequently performed at U.C. Davis. Two members of the band, Jozef Becker and Nancy Becker, would join Miller in Game Theory. Alternate Learning was disbanded in early 1982.

Meaning of "Game Theory"

Scott Miller chose to name his new band "Game Theory" as an allusion to the mathematical field of game theory, which he described as "the study of calculating the most appropriate action given an adversary, ... someone who was thinking against you, and you had to organize what his moves could be, and what your moves should be, to give yourself the minimum amount of failure."[5] In a 1988 interview, Miller stated, "It's a theory of probability that's a mathematical discipline that more or less has been applied improperly to real-life situations. It's just that idea of a set of rules that gets misused that intrigued me about it ... kind of a telling comment on life in general—that you just have to have some sort of set of rules, but who knows what the set of rules should be."[6] That theme, according to Miller, was what many Game Theory songs were about: "Always be wary of the superstructure of whatever situation you're in. It may just be that the whole game that you're into is something very bogus and you should get out."[6]

Early Davis-based years (1982–1985)

By mid-1982, Scott Miller had assembled the first iteration of Game Theory,[7] with himself as lead guitarist and vocalist. The group consisted of Miller, Nancy Becker (keyboards, vocals), Fred Juhos (bass, guitar, vocals), and Michael Irwin (drums).

The first Game Theory album was the Blaze of Glory LP, released on Rational Records in 1982. Due to a lack of funds to both press the album and print a jacket, a thousand copies of the LP were packaged in white plastic trash bags with Xeroxed cover art glued to each bag.[7][8]

Nearly thirty years after the release of Blaze of Glory, Harvard professor Stephanie Burt described it as "true to the wordy awkwardness ... of the nerd stereotype, and yet true to the visceral power, the sexual charge, in guitar-based Anglo-American pop. The songs, and the people depicted in the songs, attempted to have fun, to act on instinct, but they knew they were too cerebral to make it so, except with like-minded small circles of puzzle-solvers."[2]

With Dave Gill replacing Michael Irwin on drums, two 12-inch EPs followed. In 1983, the group released the six-song EP Pointed Accounts of People You Know, recorded at Samurai Sound Studio, which was co-owned by Gill. The group then recorded the five-song Distortion EP in December 1983 (released 1984), with The Three O'Clock's Michael Quercio producing. The first three releases, originally released on Rational, were anthologized by Alias Records in 1993 as the Distortion of Glory CD.

The early Game Theory was described as a "pseudo-psychedelic pop quartet" for which Miller sang and wrote "almost all of the material."[7] On the first three releases, Miller shared co-writing credits on "The Young Drug" with Alternate Learning's Carolyn O'Rourke, and on "Life in July" with Nancy Becker. Miller also included three songs that were written by Fred Juhos, and later defended the decision to record Juhos's songs as a Beatles-like "relief from seriousness",[9] though only one was included in the Distortion of Glory compilation.[10] Juhos's contributions were criticized as failing to mesh with Miller's, and Miller later mused, "It's funny that his stuff wasn't popular. We all had the impression that no one was ever going to get into my stuff and that his one or two would be the ones to catapult us to fame."[9]

Reviewers of Distortion of Glory wrote that the band had improved with each successive EP, both featuring "some stellar material."[8][10] Notable songs included "The Red Baron", cited as "heartbreaking ... an anguished acoustic lost-love song leavened by keyboardist Nancy Becker's mocking 'fifty or more' backing vocal,"[10] as well as "Shark Pretty," which featured guest lead guitar by Bowie sideman Earl Slick (credited as Ernie Smith).[10]

In 1984, the Dead Center LP was released in France, on the Lolita label. Dead Center was a compilation of selected tracks from Pointed Accounts of People You Know and Distortion, with three additional tracks including the group's cover of "The Letter" (a 1967 hit for the Box Tops with Alex Chilton's vocals).

Real Nighttime, recorded in July 1984, marked the entrance of Mitch Easter as producer for the band's remaining releases. Easter was also credited as a guest musician on Real Nighttime, along with Quercio and Jozef Becker.

The album was well-reviewed, appearing in the Village Voice's annual poll of 1984's best releases.[11] One critic said the album walked "a fine line between pretension and genius." Miller contributed liner notes he penned in the style of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, and the record sported "chiming guitars and great pop melodies" described as "breathtaking."[12]

Reviewers wrote, and Miller later confirmed, that a recurring theme in the lyrics of Real Nighttime was life after college, which Miller paired with the intuition that "freedom had a strong aspect of being bad news."[12][13] The song "24" placed the narrator at the cusp of a quarter-life crisis, as a self-conscious young adult whose mixed feelings established that he "doesn't know where he fits, or to how to live on his own, in a post-collegiate milieu."[2] The theme continued with allusions to finding one's own direction and leaving the nest, as in "Curse of the Frontier Land" ("A year ago we called this a good time"), and "I Mean It This Time" ("Give me all the gin I need, for I may not be this strong when I call my parents and tell them they've been wrong.")[12]

After commencing a national tour for Real Nighttime in October 1984, but before the album's 1985 release, the group went through a wholesale change in personnel, with only Miller remaining. According to Spin, the band had "lost one original member to motherhood and one to Jesus."[14] As a result, a photograph of Miller was substituted for a photograph of the full group that had previously been taken for the album cover.[15]

In 2013, after Scott Miller's death, the group's surviving members from this period (including both Irwin and Gill) briefly adopted the nickname "Game Theory 1.0," coined by Juhos during planning of the band's July 2013 reunion performance in a memorial tribute to Miller, to describe the pre-1985 version of the group's line-up.[16]

The Big Shot Chronicles (1985–1986)

By early 1985, Miller had moved from Davis to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he assembled a new lineup featuring keyboardist Shelley LaFreniere, drummer Gil Ray and, on bass, Suzi Ziegler.[17] The San Francisco version of Game Theory commenced a new national tour supporting Real Nighttime in 1985. The tour over, Ziegler left the band.[17]

The Big Shot Chronicles was recorded in September 1985 at Mitch Easter's Drive-In Studio in Winston-Salem, during the middle of the band's tour. Twenty years later, Miller recalled the sessions as "the most effortless studio experience I've ever had," taking place "in a period of my life when being involved with the music business was surprisingly enjoyable."[18]

Billboard pointed to The Big Shot Chronicles' "crisp, moody pop songs," taking note of Miller's high tenor vocals "sung in a self-described 'miserable whine'", and adding that Easter lent "an assured production touch" to this "collegiate fave."[19]

According to Spin, the 1986 album sold more copies in its first few weeks of release, thanks to a distribution deal with Capitol Records, than all of Game Theory's previous records combined.[14] Spin's review paired The Big Shot Chronicles with Real Nighttime by calling both albums "a rare commodity ... a pop record that can actually make you laugh and cry and squirm all at once."[14] The Big Shot Chronicles was distinguished as "harsh, dense, and metallic-sounding," and "damned ambitious as pop fare goes nowadays, with difficult time signatures, criss-cross rhythms, off-beat chordings, and surreal, vertiginous lyrics."[14]

Among college audiences, a contemporaneous review pointed to the band's originality in a genre "so codified that a little change in tradition is apocalyptic," citing the band's experimental notes as quirky and bizarre, yet "such loving care is taken with the obvious influences that you appreciate the music for simply reaffirming everything that's right about pop. It's one of the most important reasons for liking Game Theory, because any band with good taste is worth saving from obscurity."[20]

Decades later, in the 2007 book Shake Some Action: The Ultimate Power Pop Guide, The Big Shot Chronicles was ranked No. 16 out of the "Top 200 power pop albums of all time."[18] The reviewer noted, "Nowhere are Miller's eccentricities more consistently tuneful and genius-like than on The Big Shot Chronicles," citing the song "Regenisraen" as "absolutely gorgeous, hymn-like," among other "top-shelfers."[18] The release was, however, "surprisingly passed over by the buying public."[21]

Lolita Nation and Two Steps from the Middle Ages (1986–1988)

For the band's October–November 1986 national tour supporting the release of The Big Shot Chronicles, Game Theory took on two new members, resulting in the line-up of Scott Miller (lead vocal, guitars), Shelley LaFreniere (keyboards), Gil Ray (drums), Guillaume Gassuan (bass), and Donnette Thayer (backing vocal, guitars). Thayer, who was then Miller's girlfriend, had been a guest musician on Game Theory's first album, Blaze of Glory.[22] This iteration of the band recorded two albums, released in 1987 and 1988.

In a review of the double set Lolita Nation, Spin cited it as "some of the gutsiest, most distinctive rock 'n' roll heard in 1987," with "sumptuous melodic hooks ... played with startling intensity and precision," while simultaneously noting that the band "elected to shinny way out on an aesthetic limb" with "a thoroughly perplexing conglomeration of brief instrumental shards and stabs".[23] Miller told the San Francisco Chronicle that, with Lolita Nation, he "wanted to throw away some of the givens. It's meant to have a lot of unexpected things happening on it without being abrasive or industrial," labeling the music "experimental pop."[11] The CD version of Lolita Nation, long out of print, has since become a collector's item.

The group's 1988 release, Two Steps from the Middle Ages, took a less experimental approach, but despite numerous positive reviews and airplay on college radio, the album failed to reach a mainstream audience. Spin wrote:

Good — even great — pop songs are Scott Miller's specialty ... creating essential California rock 'n' roll for the 80s – tense, bristling energy, ingenious hooks and haunting melodies that ought to spell commercial potential. But the albums have remained stuck in the cultist-critic-college DJ loop. One problem is that Game Theory's obvious debt to Alex Chilton ... and their association with Mitch Easter ... got them lumped in with a whole genre of pop-for-pop's-sake smarty-pants, too coyly clever for their own good. But Game Theory has always rocked harder and thought bigger than the other "quirky popsters."[24]

Practical factors also got in the way of greater success. Soon after the release of Two Steps, their record label, Enigma Records, went out of business. In addition, there were conflicts within the group. After the 1988 tour, Donnette Thayer left the group to form Hex with Steve Kilbey of The Church.[25] LaFreniere and Gassuan left the group at that time as well, and Ray sustained a disabling back injury that rendered him temporarily unable to play drums.

Touring and final recordings (1989–1990)

In 1989, Miller convened another new version of Game Theory, which toured in 1989 and 1990. The line-up consisted of Miller (lead vocal, guitars), Michael Quercio (bass, drums, backing vocals), Jozef Becker (drums, bass), and Gil Ray, who was shifted by Miller from drums to playing guitar and keyboards. Jozef Becker had been a member of Miller's previous band Alternate Learning, and had played as a guest musician on earlier Game Theory releases. Quercio, best known for his previous work as frontman of The Three O'Clock, also had a long affiliation with Game Theory, having produced the 1984 Distortion EP, and having appeared as a guest musician on Real Nighttime and Lolita Nation.

Prior to the group's 1989 "mini-tour" of the Northwestern United States, Ray was a victim of random street violence in San Francisco, resulting in a serious eye injury. Ray ultimately left the group in 1990, and the group briefly continued as a trio.[9]

Game Theory's penultimate recording sessions took place in April 1989, when Nancy Becker, the group's original keyboard player and backup vocalist in the early 1980s, returned to record new versions of three songs for the compilation Tinker to Evers to Chance.[4] The re-recorded songs included one Alternate Learning song, and two from the band's first LP, Blaze of Glory.

In late 1989, the line-up of Miller, Quercio, Ray, and Jozef Becker recorded a demo in San Francisco, co-produced by Miller and Dan Vallor, with four songs that included "Inverness" and "Idiot Son" (both later to be performed by the Loud Family) and, with Quercio taking on lead vocals, "My Free Ride."[26]: 90 The London-based tabloid Bucketfull of Brains wrote, "One listen to this latest demo ... and you can't help but wonder if pop music can get any better than this."[27]

In a 1990 interview promoting the release of Tinker to Evers to Chance, Miller laughed that Game Theory stood at "a rocky pitfall-ridden crossroad," and Quercio noted, "When a major label hears someone like Scott or me sing, they say, 'That doesn't really sound like anybody,' and don't know what market to plug it into ... Sometimes originality is your worst enemy."[27]

Transition to the Loud Family (1991)

By 1991, Quercio had left Game Theory, opting to return to Los Angeles to form the band Permanent Green Light.[28][29] With Jozef Becker remaining as drummer, Miller recruited three new members to join Game Theory in 1991.[30] This new line-up had rehearsed several times as Game Theory before Miller decided that the differences in sound and energy warranted a new name for the group, which began performing in the Bay Area in 1991 as the Loud Family.[30][31] Game Theory's Gil Ray later returned to drumming as a member of the Loud Family, beginning with their 1998 album Days for Days.

Game Theory after Scott Miller

Reunion of Game Theory (2013)

Scott Miller had been making preparations to reunite Game Theory before he died unexpectedly on April 15, 2013.[16]

The surviving original members of Game Theory reunited on July 20, 2013, to perform a memorial concert in Miller's hometown of Sacramento.[32] Game Theory's 2013 line-up included Nancy Becker (keyboards, backing vocals), Fred Juhos (bass, piano), Michael Irwin (drums), Dave Gill (drums), and lead vocalist Alison Faith Levy of the Loud Family. Guest performers included Steve Harris of Urban Sherpas[33][34] (lead guitar), and Bradley Skaught of The Bye Bye Blackbirds (vocals). An acoustic opening set was performed by Game Theory members Gil Ray (guitar, vocals) and Suzi Ziegler (vocals), with Alison Faith Levy (vocals).[16][35]

Supercalifragile (2017)

Miller's record label, 125 Records, revealed after Miller's death in April 2013 that "Scott had been planning to start recording a new Game Theory album, Supercalifragile, this summer, and was looking forward to getting back into the studio and reuniting with some of his former collaborators."[36] Supercalifragile was to be the band's first album of new material since Two Steps from the Middle Ages in 1988.[37]

In September 2015, Miller's wife Kristine Chambers announced that she and Ken Stringfellow had teamed to produce a finished recording from the source material for Supercalifragile that Miller had left behind in various stages of completion, "including fully-formed songs and many other ideas, sketches, lyrics, even musical gestures and snippets of found sound."[38] A preliminary decision to release the album under Scott Miller's name, using the title I Love You All,[38][39] was later reconsidered in favor of Miller's original plans for a Game Theory project.

On May 5, 2016, it was announced that the project, now under Miller's planned title Supercalifragile as the sixth and final Game Theory album, would be released in early 2017.[40] A Kickstarter campaign, created to fund the pressing and other expenses involved with completing the album, was fully funded within two weeks.[41]

Recording sessions that included Anton Barbeau, Jozef Becker, Stéphane Schück, and Stringfellow took place in the summer of 2015 at Abbey Road Studios in London.[38] Sessions with Game Theory members Nan Becker, Dave Gill, Gil Ray, and Suzi Ziegler, in late May and early June 2016, were held at Sharkbite Studio in Oakland.[42] Additional members of Game Theory who appeared included Fred Juhos, Donnette Thayer, and Shelley LaFreniere, along with The Loud Family's Alison Faith Levy.[40][41]

Other friends and former collaborators involved as performers and co-songwriters included Aimee Mann, Jon Auer of the Posies, Doug Gillard, Ted Leo, Will Sheff, and Matt LeMay.[43][41] The contributors also included Peter Buck of R.E.M., John Moremen, and Jonathan Segel. Mitch Easter, Game Theory's former producer, played guitar, drums, and synth on the song "Laurel Canyon," and mixed two tracks.[41]

Drummer Gil Ray died on January 24, 2017, at the age of 60.[44]

Supercalifragile was released in August 2017, first to Kickstarter backers and then publicly through Bandcamp on August 24.[45]

Reissues of Game Theory albums

Rarity and unavailability

In 1993, Alias Records (which had recently signed the Loud Family) re-released the Game Theory albums Real Nighttime and The Big Shot Chronicles on CD, with additional bonus tracks. Alias also released the CD compilation Distortion of Glory, combining Game Theory's Blaze of Glory LP and material from the Pointed Accounts and Distortion EPs.

For over 25 years, from the time of their initial release on Enigma until after Miller's death, the albums Lolita Nation (1987) and Two Steps from the Middle Ages (1988), and the compilation Tinker to Evers to Chance (1990), were not re-issued on CD and became rare collectors' items. Despite approaches by more than one label and Miller's public offer of cooperation, Game Theory's catalog remained out of print until 2014, due to what Miller understood to be rights issues that prevented physical access to the original master recordings.[46]

Over the decades, the increasing difficulty of finding copies of Game Theory albums contributed to the band's inability to transcend what Miller described as "national obscurity, as opposed to regional obscurity."[47] In 2013, MTV wrote of "Miller's indelible output" and "Game Theory's transcendent tunes" as a "legacy ... ready and waiting for discovery."[1]

Reissues on Omnivore Recordings (2014–)

In July 2014, Omnivore Recordings announced their commitment to reissue Game Theory's recordings, remastered from the original tapes.[48] Noting that Miller's work with Game Theory had been out of print and "missing for decades," Omnivore stated that they were "pleased to right that audio wrong" with a series of expanded reissues of the group's catalog.[49] The reissue series is produced by Pat Thomas, Dan Vallor (Game Theory's tour manager and sound engineer during the 1980s), and Grammy-winning producer Cheryl Pawelski.[50]

The first in the series, an expanded version of Game Theory's 1982 debut album Blaze of Glory, was released in September 2014, on CD and vinyl.[48] In addition to the 12 original tracks, the reissue was supplemented with 15 bonus tracks (four from Alternate Learning, and 11 previously unissued recordings).[51] The first pressing of the reissued vinyl LP was on translucent pink vinyl, with black to follow.[52] The reissue also included a booklet with essays and remembrances from band members and colleagues, including Steve Wynn of The Dream Syndicate.[50] The booklet also included previously unreleased images by photographer Robert Toren, some of which appeared in Omnivore's promotional video for the release launch.[53]

Omnivore's November 2014 expanded reissue of Dead Center, on CD only, included material from the Game Theory EPs Pointed Accounts of People You Know (1983) and Distortion (1984), reissued on vinyl only.[54][55]

The reissue of Real Nighttime (1985), the first of Game Theory's albums to be produced by Mitch Easter, was released in 2015 on CD and red vinyl, with 13 bonus tracks and liner notes that included new essays by Byron Coley and The New Pornographers' A.C. Newman, as well as an interview with Easter.[56]

Departing from chronological order, Omnivore's February 2016 reissue of Lolita Nation was a double CD set, with the second disc featuring 21 bonus tracks. A concurrent double LP release, with its first run in a limited edition on dark green translucent vinyl, included a download card providing the full 48-track CD program.

Omnivore followed with reissues of The Big Shot Chronicles in September 2016 and Two Steps from the Middle Ages in June 2017.

In 2020, Omnivore concluded the series of reissues by releasing Across the Barrier of Sound: PostScript, a compilation album consisting of material recorded in 1989 and 1990, featuring previously unreleased songs from Game Theory's final lineup.

Discography

- Studio albums

- Blaze of Glory (1982)

- Real Nighttime (1985)

- The Big Shot Chronicles (1986)

- Lolita Nation (1987)

- Two Steps from the Middle Ages (1988)

- Supercalifragile (2017)

Timeline

References

- ^ a b Allen, Jim (April 18, 2013). "Listen to All Eight of Scott Miller's Game Theory Records". MTV Hive. Archived from the original on 2013-12-10.

- ^ a b c Burt, Stephen (Winter 2011). "Game Theory, or, Not Exactly the Boy of My Own Dreams" (PDF). New Haven Review (9): 6–25. Archived from the original on 2012-06-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) Reprinted as Burt, Stephen (April 18, 2013). "Game Theory: "Pure pop for nerd people," the greatest unknown '80s band". Salon. Archived from the original on 2013-04-19. - ^ DeRogatis, Jim (1996). Kaleidoscope Eyes: Psychedelic Rock from the '60s to the '90s. Citadel Underground Series. Carol Pub. Group. p. 173. ISBN 9780806517889.

- ^ a b Miller, Scott (1990). Tinker to Evers to Chance (CD booklet). Game Theory. Enigma Records.

- ^ Guzman, Rafer (March 6, 1996). "Star on hold: Faithful following, meager sales". Pacific Sun. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2014..

- ^ a b Woelke, Tina (December 1988). "Where Have You Gone, James Joyce? A Nation Turns Its Lolita Eyes To You". Non*Stop Banter. Archived from the original on 2013-11-06. Retrieved 2014-01-24..

- ^ a b c Gimarc, George (2005). Punk Diary: The Ultimate Trainspotter's Guide to Underground Rock, 1970-1982. Hal Leonard Corp./Backbeat Books. p. 676. ISBN 9780879308483.

- ^ a b Durkin, Thomas (November 12, 2003). "Interview with Scott Miller of the Loud Family". Glorious Noise. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12.

- ^ a b c Cost, Jay (Fall 1990). "Scott Miller Interview". Bucketfull of Brains (38). London, UK. Archived from the original on 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2013-11-08..

- ^ a b c d Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 447–448. ISBN 9780879306533.

- ^ a b Arnold, Gina (May 22, 1988). "Game Theory: 916 Pop Band Goes 800". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013..

- ^ a b c Cooper, Kim; Smay, David (2005). Lost in the Grooves: Scram's Capricious Guide to the Music You Missed. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 0415969980.

- ^ Miller, Scott (July 17, 2007). "Ask Scott". Archived from the original on 2013-11-01.

- ^ a b c d Wuelfing, Jr., Howard (February 1987). "Big Shots: Game Theory Shakes Its Alex Chilton Albatross". Spin. 2 (11): 11.

- ^ Toren, Robert (August 5, 2013). Photo Robert (Photographer's notes). Tumblr. Archived from the original on 2013-12-18.

- ^ a b c Cosper, Alex (July 22, 2013). "Sacramentans pay tribute to musician Scott Miller". Sacramento Press. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02.

- ^ a b Cosper, Alex (July 26, 2013). "The Life of Scott Miller". "Video of the Day" review. SacTV.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12.

- ^ a b c Borack, John M. (2007). Shake Some Action: The Ultimate Power Pop Guide. Not Lame Recordings. p. 52. ISBN 978-0979771408.

- ^ "Game Theory: The Big Shot Chronicles". Billboard. Reviews. Vol. 98, no. 36. September 6, 1986. p. 80.

- ^ Bliss, Jeff (August 27, 1986). "Chronicles reaffirms worth of musical groups with good taste". Daily Collegian. Penn State. p. 34. Archived from the original on 2013-12-18.

- ^ Strong, Martin C. (2003). The Great Indie Discography. Canongate Books. p. 345. ISBN 9781841953359.

- ^ Miller, Scott (1982). Blaze of Glory (LP insert). Game Theory. Rational Records.

- ^ Wuelfing, Jr., Howard (January 1988). "Game Theory: Lolita Nation". Spin. 3 (8): 24–25.

- ^ Hill, Christopher (April 1989). "The Stuff of Life". Spin. 5 (1): 16.

- ^ Lurie, Robert Dean (2012). No Certainty Attached: Steve Kilbey and The Church. Verse Chorus Press. ISBN 9781891241949.

- ^ Bruno, Franklin (Spring 2014). "Blaze of Gl—: Scott Miller: An Appreciation". The Pitchfork Review (2): 88–103. ISBN 9780991399215.

- ^ a b Moore, Robb (Fall 1990). "Game Theory". Bucketfull of Brains (40). London, UK.

- ^ Mason, Stewart. "About Permanent Green Light". MTV. Artists. Archived from the original on 2013-12-12.

- ^ Green, Jim. "Permanent Green Light". Trouser Press. Archived from the original on 2005-01-21.

- ^ a b Coley, Byron (May 1993). "Miller Genuine Craft: Scott Miller makes a subtle move from his Game Theory into the Loud Family". Spin. 9 (2): 26.

- ^ Durkin, Thomas (May 7, 2008). "The Loud Family – Plants and Birds and Rocks and Things". WTFF. Written as DJ Murphy. Archived from the original on 2013-12-05.

- ^ Yudt, Dennis (July 18, 2013). "A way with words: Friends pay tribute to Scott Miller, the late Davis artist who combined his love for music and literature into an influential career". Sacramento News & Review. Archived from the original on 2013-11-19.

- ^ "Urban Sherpas" (official website). Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ^ Steve Harris discography at MusicBrainz.

- ^ "Game Theory Concert Setlist at Shine, Sacramento, CA". Setlist.fm. July 20, 2013.

- ^ "Loud Family (official website)". Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (April 18, 2013). "Scott Miller, Game Theory and Loud Family Singer, Dead at 53". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2013-10-21.

- ^ a b c "Scott Miller: I Love You All". Tilt.com. September 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gottlieb, Jed (November 10, 2015). "Reissues and biography boost legend of Game Theory's late leader". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on 2015-11-10.

- ^ a b Gibbs, Ryan (May 5, 2016). "Music news: Kickstarter launched for final Game Theory album". The Young Folks. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06.

- ^ a b c d West, B.J. (May 5, 2016). "Campaign: About this project". Supercalifragile by Scott Miller's Game Theory. Kickstarter. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06.

- ^ West, B.J. (June 1, 2016). "Update #5: Half Time!". Supercalifragile by Scott Miller's Game Theory. Kickstarter. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02.

- ^ Robinson, Collin (May 6, 2016). "Crowdfunded Final Game Theory Album Features Members of the Posies, R.E.M., The Both". Stereogum. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06.

- ^ "Gil Ray: 1956–2017". Loud Family. January 25, 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-01-26.

- ^ "Supercalifragile, by Game Theory". Bandcamp. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Miller, Scott (February 2, 2004). "Ask Scott: Archive". Archived from the original on 2013-11-05.

- ^ Hann, Michael (April 18, 2013). "Scott Miller may not be a household name, but his death lessens pop". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 2013-11-14.

- ^ a b Davidson, Eric (July 15, 2014). "Game Theory Catalog To Be Reissued: Blaze Of Glory out September 2". CMJ. Archived from the original on 2014-07-15.

- ^ Omnivore Recordings (July 14, 2014). "Release: Blaze of Glory". Archived from the original on 2014-07-15.

- ^ a b Mills, Fred (July 15, 2014). "Omnivore Kicks Off Ambitious Game Theory Reissue Program". Blurt. Archived from the original on 2014-07-17.

- ^ Ragogna, Mike (July 15, 2014). "Game Theory's Blaze of Glory Expanded". Trafficbeat. Archived from the original on 2014-07-23.

- ^ "Game Theory's 1982 debut 'Blaze of Glory' to be reissued with 11 unreleased bonus tracks". Slicing Up Eyeballs. July 15, 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-07-15.

- ^ Omnivore Recordings (July 14, 2014). Omnivore Game Theory launch trailer (official trailer). YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13.

- ^ "Release: Dead Center". Omnivore Recordings. October 15, 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. (Omnivore Catalog No. OV-103, UPC: 816651016549).

- ^ "Release: Distortion". Omnivore Recordings. October 15, 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. (Omnivore Catalog No. OV-102. UPC: 816651016525).

- ^ "Game Theory Real Nighttime" (Press release). Los Angeles, California: Omnivore Recordings. January 26, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-01-26.

External links

- Official website

- Game Theory at AllMusic

- Game Theory discography at Discogs