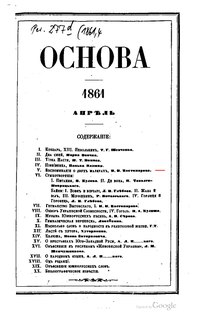

Osnova

The Ukrainian journal Osnova (meaning Basis in English) was published between 1861 and 1862 in Saint Petersburg. It contained articles devoted to life and customs of the Ukrainian people, including regular features about their wedding customs and traditions.[1][2] Prominent figures were associated with the journal Osnova included Ukrainian intellectuals such as Volodymyr Antonovych and Tadei Rylsky (father of Maksym Rylsky), as well as poet Pavlo Chubynsky.[3]

Overview

[edit]In the Russian Empire expressions of Ukrainian culture and especially language were repeatedly persecuted, for fear that a self-aware Ukrainian nation would threaten the unity of the Empire.

In 1811, by the Order of the Russian government the Kyiv Mohyla Academy (established in 1632) was closed and outlawed.

In 1847, the Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius was terminated. The same year Taras Shevchenko was arrested and exiled for ten years, and banned for political reasons from expressing his views.

The journal was published monthly from January 1861 to September 1862 in St. Petersburg. Some of its texts were published in Russian.

Publishers:

- Vasyl Bilozersky (editor),

- Panteleimon Kulish,

- Mykola Kostomarov,

- Alexander Kistyakovsky (Secretary),

- M. Scherbak and others.

Hanna Barvinok (real name Oleksandra Bilozerska-Kulish) who was Vasyl Bilozersky's sister and Panteleimon Kulish's wife also took part in the creation of the journal "Osnova".[4]

"The region, the study of which the "Osnova" will be devoted, is inhabited mainly by the southern Russian people," - said the magazine's program. The editorial board stated that it was "opening its journal for works in both native languages," emphasizing that "in our time, the question of whether it is possible and whether to write in Ukrainian is a matter of course". The editorial board of "Osnova" called to pay special attention to the "practical significance of the vernacular in teaching and preaching."[5]

In 1862, Pavlo Chubynsky associated with Osnova was exiled for seven years out of Ukraine to Arkhangelsk.[6][7] The magazine Osnova was discontinued for financial reasons.[8]

Difficulties at the opening stage

[edit]The return of Taras Shevchenko gave a new powerful impetus to Ukrainian life in St. Petersburg. It is no coincidence that in the summer of 1858 the Ukrainian Community began to operate, aiming at publishing and educational activities. On her instructions, in October 1858, P. Kulish applied to the Ministry of Education for permission to publish the magazine "Khata" (full name: "Khata: South-Russian Journal of Literature, History and Agriculture"). Although the magazine was not supposed to be political, the ministry appealed to the Third Branch and rejected Kulishev on the basis of his recall.[9]

The refusal was due to his participation in the Cyril and Methodius Society ten years ago. As P. Kulish himself remarked: "the minister refused, and he refused, and it was me who did not, in fact, oppose the idea of the magazine".[10]

When a year later another relative of the Cyril and Methodius Society, a relative of P. Kulish V. Belozersky, applied to publish the magazine, the gendarmerie also objected, but less vigorously. After some time, permission was granted. It is possible that the measures of "enlightened people from St. Petersburg Russians" mentioned by P. Kulish in a letter to S. Aksakov helped. The first announcement of the forthcoming publication of the Fundamentals was published in June 1860, and the first issue was published in January 1861.[11]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "The Ukrainian magazine Osnova at "Folk Weddings of Ukraine"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ "Osnova Dictionary".

- ^ Aleksei I. Miller, The Ukrainian Question: The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century[permanent dead link] («Украинский вопрос» в политике властей и русском общественном мнении. вторая половина XIX в.), Central European University Press, Budapest, 2003, pp. 76-77. ISBN 963-9241-60-1

- ^ "Вхід". toloka.to (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ Osnova. Publication announcement and Program. Appendix k№ 1 for 1861 - P. 1.

- ^ Валуевский циркуляр, full text of the Valuyev circular on Wikisource(in Russian)

- ^ XII. СКОРПІОНИ НА УКРАЇНСЬКЕ СЛОВО. Іван Огієнко. Історія української літературної мови

- ^ Yuri Zemsky. Polish, Russian and Ukrainian elites in the competition for the Right Bank Ukraine in the mid-nineteenth century. Khmelnytsky .: 2011 p.230 - 234.

- ^ Andriichuk, T. S. (2019). "Партисипаторна та деліберативна демократія в сучасному політичному дискурсі". Політичне життя (1): 45–51. doi:10.31558/2519-2949.2019.1.6. ISSN 2519-2949.

- ^ Гринівський, Тарас (2021-05-20). "Українське книговидання Буковини кінця ХІХ – початку ХХ ст.: організаційний та тематичний аспекти". Український інформаційний простір. 1 (7): 138–148. doi:10.31866/2616-7948.1(7).2021.233884. ISSN 2617-1244.

- ^ "Александровский И.С. Образовательное измерение культурной политики Российской империи и "украинский вопрос" в XIX столетии". Genesis: исторические исследования. 10 (10): 59–65. October 2018. doi:10.25136/2409-868x.2018.10.27443. ISSN 2409-868X.